It doesn't take a genius to know that injuries to Soldiers from roadside bombs and their resulting vehicle crashes could take a serious toll on readiness, the Army's No. 1 priority. In fact, when it comes to testing materials or providing data to evaluate solutions to reduce injuries during these events, it takes a real dummy.

That's a good thing for the interior blast mitigation team in the Army's Occupant Protection Laboratory at Selfridge Air National Guard Base, Michigan. They use nine crash test dummies in simulated and live tests to measure blast and crash forces on the human skeletal system to improve survivability.

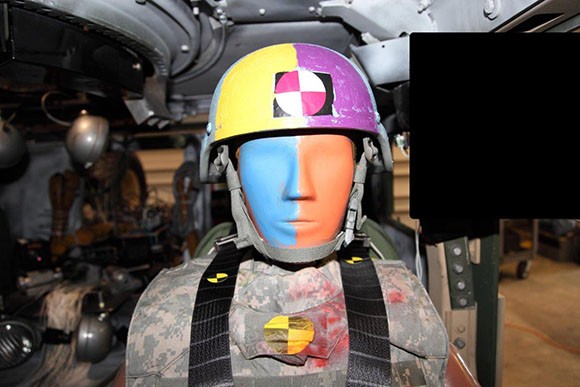

These mannequins, known formally as full-scale anthropomorphic test devices, or life-size ATDs, range from 5 feet tall and 100 pounds to 6 feet tall and 225 pounds, representing about 90 percent of all Soldiers.

Each ATD has a variety of sensors that collect data mined by 45 U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development and Engineering Center engineers, physicists and technicians. The mannequins are outfitted with up to 80 pounds of Army field gear before being strapped into seats. Then they are dropped from a tower, placed into simulators or vehicles to be crashed, have their heads slammed against interior vehicle walls, or get blown up in live field tests -- all in the name of readiness.

The OPL, aligned under TARDEC's Survivability directorate, has four sub-labs tucked inside a hangar about 20 miles from TARDEC's main campus at the Detroit Arsenal. The ATD Certification Laboratory and Head Impact Laboratory test exactly what their names suggest. The Floor Interface Technology Accelerator tests vehicle floor solutions to assess lower extremity injuries from underbody explosive devices, while the Sub-System Drop Tower simulates a blast from under a vehicle.

A typical test on the drop tower involves a vehicle seat with restraints and an instrumented dummy, according to AnnMarie Meldrum, lab manager for the OPL. Data is collected from the ATDs after the seat drops to measure effects on the body via the ATDs' sensors.

Risa Scherer, supervisory team leader for the interior blast mitigation team, explained that after a blast, a vehicle will slam to the ground. Likewise, she said, "When the tower drops, it ends with a sudden stop. That stop causes a reaction in the body similar to what a blast does," which typically leads to injuries to Soldiers' spines and lower legs, and to their heads from hitting the interior of the vehicle.

"Soldiers get all types of injuries -- spine, pelvis, neck, back; it depends on the size of the blast," Scherer said. "We try to keep them alive and uninjured. A lot of blast events are injuring the lower leg; the goal is not to do that. We test solutions so that doesn't happen, so they can get out and do the mission. The drop tower is a quick, economical way of testing safety solutions to help develop them to go onto the full vehicle."

Once the team has collected data from the ATDs, it provides injury assessment reports to whoever ordered the tests. "Most of the stuff we do is tied to occupant injuries, so they will see where it passes or fails the criteria, where they might be having some problems," Scherer said. Her team also can provide data and recommendations to engineers who design the equipment, leading to better technology to mitigate injuries.

Injuries during crashes and rollovers don't happen only after roadside blasts. "When we're not in combat, crash and rollover events are the leading cause of on-duty Soldier deaths," Scherer said.

In addition to tests in the labs, the OPL staff conducts tests in the field to mimic training and real-world mishaps. Their main function when conducting blast testing is operating the ATDs.

"When we test in the field we conduct live-fire blasts," Meldrum said. "We ship our dummies and seats to the blast location with all the equipment that's needed to record the data. We set the dummies in positions we expect the Soldiers to be sitting in to measure probable injuries."

Scherer has a group that works with the Engineer Research and Development Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana. "We have a generic vehicle that we blow up to test different technologies," she said. "So AnnMarie's team will go down, instrument the vehicle, prep the vehicle, run the dummies, collect all the data, do the camera coverage. ERDC does the soil, puts the charge in and controls the blast, but AnnMarie's team controls the rest of the test," she explained.

Meldrum said that her team often conducts multiple tests in a short amount of time while on location. After each blast, they must assess damage to the dummies and the data acquisition system, make repairs and reposition the dummies for the next test.

Although the ATDs provide a lot of data, they do have limitations. "We are using dummies from the auto industry," Scherer pointed out. "They are designed for frontal crashes but we're subjecting them to blast loading." They can indicate which bones would be broken but cannot gauge injuries from burns or to organs, though organ damage may be deduced from the fractured bones around them.

To counter some of these limitations, Scherer said they are working with TARDEC engineers on a program to develop the WIAMan (pronounced Wee-a-man). The Warrior Injury Assessment Manikin will measure skeletal loads similar to what they would be during a real blast event and will provide better injury assessment data, Scherer said.

Another upcoming improvement is a new lab called the Crew Compartment Underbody Blast Simulator, or CCUBS. It will propel a platform with attached seats into the air, which will provide a more accurate simulation of a blast than the drop tower, Scherer said. "This will give us a good premise of testing various seats and compare them to each other to see which one performs best. It's quicker and will allow us to start looking more at compartments, so I can put in the seat, the instrument panel, the steering wheel and see how things are going to interact more with each other. I could put four seats on there and test them at the same time, too, and they would have the exact same input. That just gives us more capability." Construction is expected to begin this year.

When the labs aren't being used for blast mitigation, they may be used to run tests for other Army equipment. For example, "We've used the drop tower to test some electronic equipment for the bridging guys next door, just to shock it to make sure it still works," Scherer said.

Looking back at the ATDs with sensors smart enough to lead to improved Soldier survivability and readiness, calling them "dummies" doesn't give them the credit they deserve. Maybe it does take a genius.

Social Sharing