Fort Huachuca, Az. - On Aug. 13, 1917, the U.S. Army's Military Intelligence Section (later elevated to Division) created the Corps of Intelligence Police (CIP) to protect American forces in France from sabotage and subversion. CIP agents also conducted special investigations, including suspected German espionage activities, throughout the United States. The CIP had difficulty apprehending the enemy agents involved because they often fled to Mexico. Several CIP agents were stationed along the U.S.-Mexico border during this period to investigate and apprehend suspected German spies.

Two CIP agents in Nogales, Arizona, Capt. Joel A. Lipscomb and Capt. Byron S. Butcher, recruited Dr. Paul B. Altendorf to infiltrate German spy rings in Mexico. Altendorf was an Austrian immigrant to Mexico, where he served as a colonel in the Mexican army. Known to the CIP as Operative A-1, Altendorf managed to join the German Secret Service and become linked with several other German spies living in Mexico.

In January 1918, the CIP learned that Altendorf was accompanying one Lothar Witzke from Mexico City to the U.S. border. Witzke was a 22-year-old former lieutenant in the Germany navy, who alternately went by Harry Waberski, Hugo Olson and Pablo Davis, to name just a few of his many aliases. He had long been under CIP surveillance as a suspected German spy and saboteur. During the trip from Mexico City, Witzke had no suspicion that his companion was an Allied double agent taking note of Witzke's every move and indiscretion. At one point, a drunk Witzke let slip bits of information that Altendorf quickly passed on to Butcher. Specifically, Altendorf informed the CIP that Witzke's handlers had sent him back to the United States to incite mutiny within the U.S. Army and various labor unions, conduct sabotage and assassinate American officials.

On or about Feb. 1, 1918, Butcher apprehended Witzke once he crossed the border at Nogales, and a search of Witzke's luggage revealed a coded letter and Russian passport. Capt. John Manley, assistant to Herbert Yardley in the Military Intelligence Division's MI-8 Cryptographic Bureau in Washington, D.C., deciphered the letter, revealing Witzke's German connections. The letter stated: "Strictly Secret! The bearer of this is a subject of the Empire who travels as a Russian under the name of Pablo Waberski. He is a German secret agent."

While detained at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, awaiting trial, Witzke was extensively interrogated by CIP agents but refused to provide any details about his contacts, co-conspirators or alleged espionage. His trial began in August 1918, and witnesses against him included Altendorf, Butcher, Lipscomb and Manley. Witzke took the stand in his own defense and spun a fantastical tale of how he was simply a down-on-his-luck drifter framed as a German spy. The Military Commission found Witzke guilty of espionage and sentenced him to death, the only German spy thus sentenced in the United States during World War I. After the war, President Woodrow Wilson commuted his sentence to life in prison, and he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. In 1923, however, Witzke was pardoned and released to the German government.

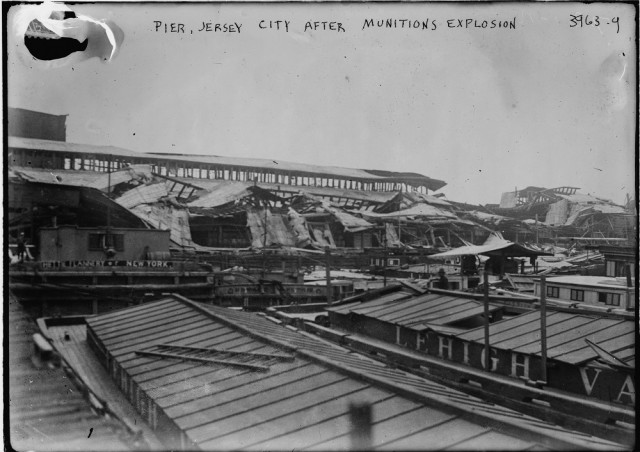

A decade later, during the international Mixed Claims Commission hearings into damages related to the war, several American lawyers revealed Witzke's role in the sabotage of the Black Tom Island munitions depot in New York Harbor on July 20, 1916. Ostensibly, he had been one of three collaborators who had placed dynamite on several barges loaded with ammunition causing a blast felt as far away as Philadelphia and Maryland. The explosion lit up the night sky, shattered windows, broke water mains and peppered the Statue of Liberty with shrapnel. Seven people were killed. Although in 1939 the Mixed Claims Commission found Germany complicit in the sabotage, Witzke and his co-conspirators, allegedly responsible for the worst act of terrorism on American soil up to that time, went unpunished. Additionally, Germany refused to pay the $50 million judgment.

The capture of Witzke and other German spies and saboteurs by the Army's counterintelligence agents undoubtedly prevented many, but not all, planned sabotage activities during the war. Such incidents poisoned relations between the United States and Germany and introduced suspicions and fear in the minds of the American public. Americans could no longer assume complete security from enemy acts of terror on U.S. soil, a reminder still valid today.

For more information on the Black Tom Island incident, see Michael Warner's "The Kaiser Sows Destruction: Protecting the Homeland the First Time Around," https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol46no1/article02.html#rfn12.

Social Sharing