WASHINGTON (Army News Service) -- In a tactical situation, the last thing a Soldier wants to do is give away his position to the enemy.

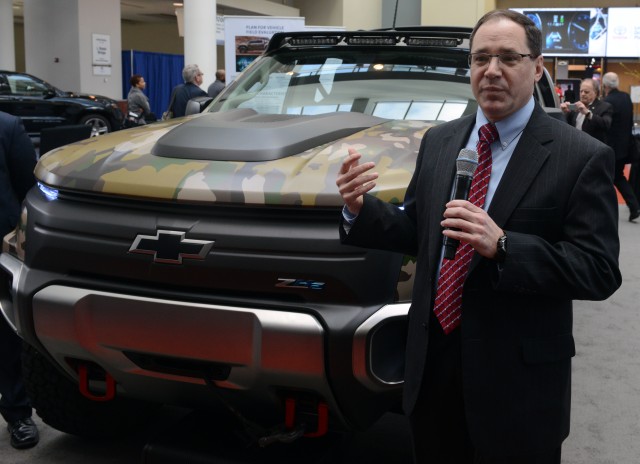

The ZH2 hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle promises to provide that important element of stealth, said Kevin Centeck. team lead, Non-Primary Power Systems, U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development and Engineering Center at the 2017 Washington Auto Show here Thursday.

The ZH2 is basically a modified Chevy Colorado, fitted with a hydrogen fuel cell and electric drive, he said. It was put together fairly quickly, from May to September, and will be tested by Soldiers in field conditions later this year.

Charley Freese, executive director of General Motor's Global Fuel Cell Activities, explained the ZH2 is stealthy because its drive system does not produce smoke, noise, odor or thermal signature. GM developed the vehicle and the associated technologies.

The vehicle provides a number of other advantages for Soldiers:

-- The ZH2 produces high torque and comes equipped with 37-inch tires that enable it to negotiate rough and steep terrain.

-- The hydrogen fuel cell can produce two gallons per hour of potable water.

-- When the vehicle isn't moving, it can generate 25 kilowatts of continuous power or 50 kW of peak power. There are 120 and 240-volt outlets located in the trunk.

-- The vehicle is equipped with a winch on the front bumper.

Dr. Paul D. Rogers, director of TARDEC, said the Army got a good deal in testing this vehicle, leveraging some $2.2 billion in GM research money spent in fuel cell research over the last several decades. The Army is always eager to leverage innovation in new technology, he added.

While GM developed the technology and produced the demonstrator, the Army's role will be to test and evaluate the vehicle in real-world field conditions over the next near.

HOW IT WORKS

Electricity drives the vehicle, Centeck said. But the electricity doesn't come from storage batteries like those found in electric cars today. Instead, the electricity is generated from highly compressed hydrogen that is stored in the vehicle by an electrochemical reaction.

As one of the two elements that make water (the other being oxygen), there's plenty of hydrogen in the world. But hydrogen isn't exactly free, Centeck pointed out. It takes a lot of electricity to separate the strong bond between hydrogen and oxygen.

That electricity could come from the grid or it could come from renewables like wind or solar, Centeck said.

Existing fuels like gasoline, propane, and natural gas can also be used to extract hydrogen, he said. The Army and GM are comparing the costs and benefits for each approach and haven't yet settled on which approach to use.

Christopher Colquitt, GM's project manager for the ZH2, said that the cost of producing hydrogen isn't the only complicating factor; another is the lack of hydrogen fueling stations.

Most gas stations aren't equipped with hydrogen pumps, Colquitt pointed out, but California and some other places in the world are in the process of building those fueling stations. For field testing purposes, the Army plans to store the hydrogen fuel in an ISO container.

Another cost involves the hydrogen fuel cell propulsion system itself. Fuel cell stacks under the hood convert hydrogen and air into useable electricity. They are composed of stacks of plates and membranes coated with platinum.

In the ZH2 demonstrator, there are about 80 grams of platinum, costing thousands of dollars, he said. But within the last few months, GM developers have managed to whittle that amount of platinum down to just 10 grams needed to produce a working vehicle, he said.

The modern-day gas and diesel combustion engine took a century to refine. Now, GM is attempting to do that similar refining with hydrogen fuel cells in just a matter of months, he said. It's a huge undertaking.

By refining the design, Colquitt explained, he means lowering cost and providing durability, reliability and high performance. Refining doesn't just mean using less platinum, he explained. A lot of other science went into the project, including the design of advanced pumps, sensors, compressors that work with the fuel cell technology.

Colquitt said the ZH2's performance is impressive for such a rapidly-produced vehicle. For instance, the fuel cell produces 80 to 90 kilowatts of power and, when a buffer battery is added, nearly 130 kilowatts. The vehicle also instantly produces 236 foot-pounds of torque through the motor to the transfer case.

The range on one fill-up is about 150 miles, since this is a demonstrator, he said. If GM were actually fielding these vehicles, the range would be much greater.

NOT READY FOR CONSUMERS

Colquitt said hydrogen fuel cell technology hasn't yet yielded vehicles for consumers, but GM is working on doing just that in the near future, depending on a number of factors, mainly the availability of fueling stations.

The Army is no stranger to the technology, he said. GM's Equinox vehicles, powered by hydrogen fuel cells, are being used on several installations. The difference is that the ZH2 is the first hydrogen fuel cell vehicle to go tactical, he said.

The value of having the Army test the vehicle is that it will be driven off-road aggressively by Soldiers, who will provide their unvarnished feedback, Colquitt said. Besides collecting subjective feedback from the Soldiers, he said, the vehicle contains data loggers that will yield objective data as well.

Testers will put the vehicle through its paces this year at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Fort Carson, Colorado; Fort Benning, Georgia; Quantico Marine Base, North Carolina; and, GM's own Proving Grounds in Michigan.

Social Sharing