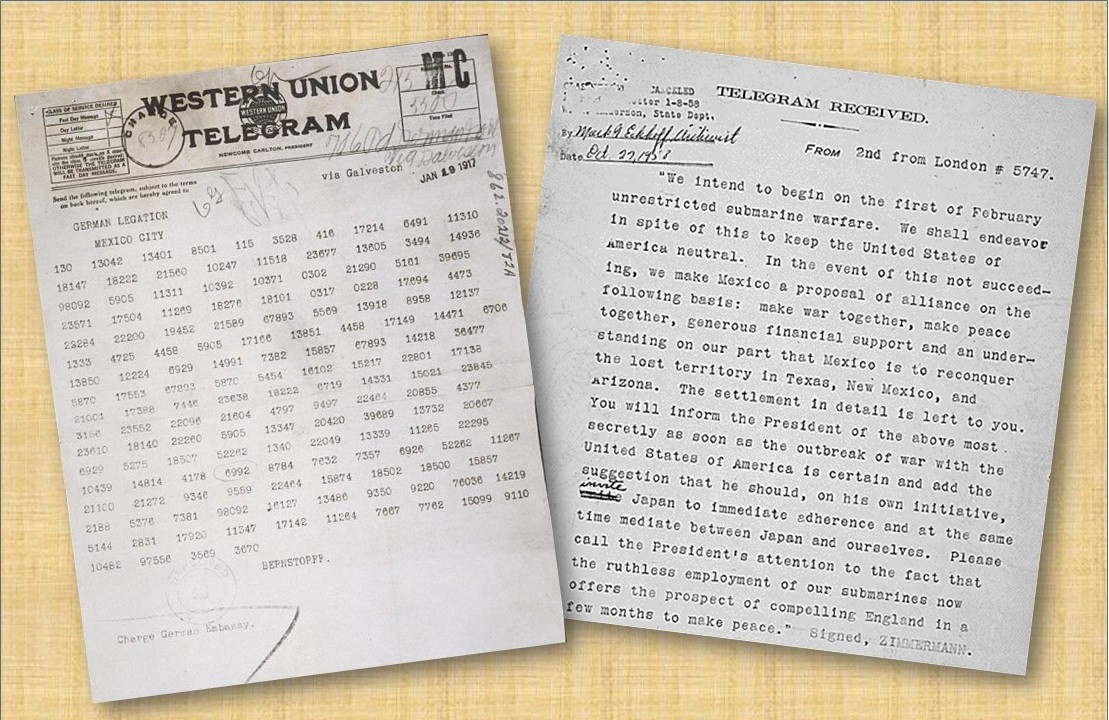

Fort Huachuca, Arizona - "…we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona."

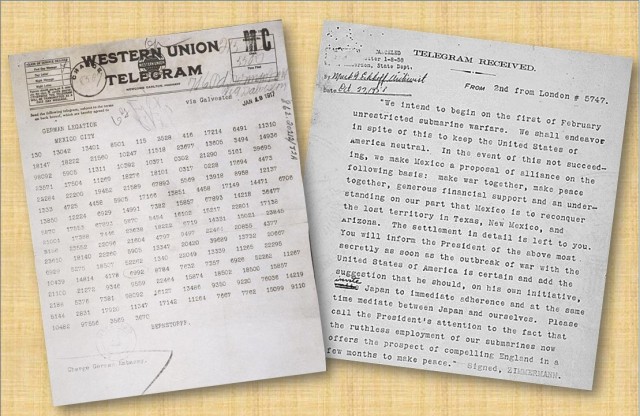

These words are extracted from the now infamous telegram from Arthur Zimmermann, the German Foreign Secretary, to Heinrich von Eckardt, German Minister to Mexico. The telegram, sent from Berlin on Jan. 16, 1917, directed Eckardt to propose an alliance between Germany and Mexico to the Mexican president in the event the United States formally entered World War I.

World War I, or the Great War as it was then known, had been fomenting in Europe for years, but the final catalyst proved to be the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in June 1914. Shortly thereafter, Germany declared war successively on Russia, France, Belgium and Portugal. The United Kingdom and other European nations quickly declared war on Germany. The war eventually embroiled nations worldwide.

The United States steadfastly retained its neutrality for two years. President Woodrow Wilson, re-elected in 1916 on the slogan "He kept us out of war," resolutely but unsuccessfully pursued a negotiated peace between the two sides. By early 1917, Germany decided to launch unrestricted U-boat warfare on all ships, neutral or belligerent, in the waters of the war zones. This effort, German planners predicted, would bring England to the brink of economic collapse and thus surrender within months.

Zimmermann knew that the U-boat war would force the United States, reluctantly but inexorably, into the war on the side of the Allies. He believed that if Germany could entice Mexico into a war with the United States, it would divert U.S. attention and ammunition shipments away from the Allies.

On Jan. 18, 1917, the telegram reached Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, the German ambassador in Washington, D.C., who was then to send it to Eckardt in Mexico. Zimmermann had audaciously sent the message over the U.S. State Department's own trans-Atlantic cable, which President Wilson had allowed Germany to use for transmitting communications related to peace negotiations. Inexplicably, Wilson had allowed those dispatches to be sent in the German code, for which the State Department did not have a codebook.

Unbeknownst to the United States, British cryptographers had been intercepting message traffic on the State Department's telegraph route. In addition, unbeknownst to both the United States and the Germans, those same British code-breakers had cracked the German diplomatic code and immediately set themselves to decoding the Zimmermann Telegram.

Incredulous at its contents, the British debated how best to notify the United States, knowing, on one hand, it would bring the United States into the war and, on the other, that it would anger the United States to know England was reading its dispatches. To prevent the latter, the British code section waited until Bernstorff sent the message to Eckardt and used that message, slightly altered from the original, to enlighten the United States of the brazen German scheme.

The British finally revealed the contents of the telegram to the United States on Feb. 23, 1917, and a week later, major newspapers around the country published the evidence of the German conspiracy. Americans reacted with a mix of disbelief and anger. Rumors that Germany had financed Mexican bandit Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916 had resulted in a comprehensive investigation by the State Department. The results of that investigation, as well as others into German intrigue in Mexico, were inconclusive, however. As a result, most Americans initially viewed the telegram as a hoax -- surely the Germans were not so foolhardy as to promise to give away part of the United States.

Ultimately, the directives in the Zimmermann Telegram came to naught; the Mexican president chose to remain neutral rather than instigate a war with its northern neighbor. Undeniably, however, knowledge of the threat of hostile action on American territory shifted public opinion in support of a war most citizens had previously marginalized. At the same time, Germany had launched the unrestricted submarine warfare it had previously threatened, resulting in the sinking of several U.S. merchant ships in late March.

The Great War, therefore, was no longer just a threat to Europe. On April 2, 1917, President Wilson requested a declaration of war from Congress, stating, "That [the German government] means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors, the intercepted note to the German Minister at Mexico is eloquent evidence. We accept this challenge of hostile purpose…." Congress overwhelmingly voted for war and ultimately, American intervention helped turn the tide in favor of the Allies and end the war.

Social Sharing