When Sgt. Christopher A. Springer received orders to report to the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) in Silver Spring, Maryland, all he knew of his impending assignment was that he would be working in a medical laboratory.

But Springer soon learned that, because of the rapid spread of Zika, he would be among the first military personnel in the country taking part in the U.S. Army's efforts to control the mosquito-borne virus.

Recognizing the threat of Zika to its service members in the outbreak zones of North and South America and Southeast Asia, the Army was moving quickly to develop a vaccine at the Department of Defense's largest biomedical research laboratory.

Zika is a flavivirus similar to yellow fever, dengue and Japanese encephalitis. Flaviviruses are the field of expertise at the institute, which dates back to 1893.

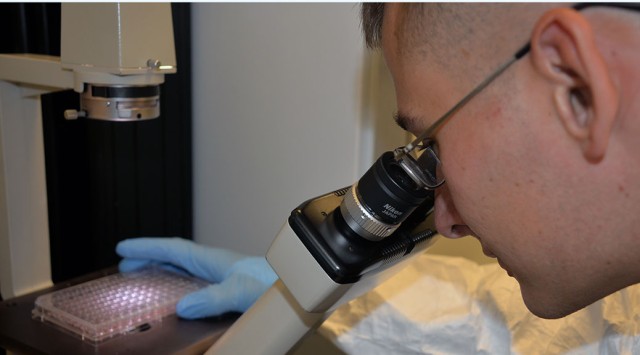

Springer was soon immersed in lab work with his other colleagues at WRAIR. He and another colleague routinely handled the majority of lab work on the Zika virus, running tests, producing paperwork and sharing the results, along with performing other essential lab duties.

Within a few months at WRAIR, the Zika purified inactivated vaccine was successfully created and Springer, a lab technician, had played a contributing role in the vaccine's development.

"I had my suspicions when I got here and saw I would be working in vaccine development," Springer said. "I definitely felt like there would be some good opportunities here, but I had no idea that something like this could ever happen."

Springer has a bachelor of science in criminal justice from Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, and an associate's degree in health science laboratory technology from George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

WRAIR LEADS THE WAY

Earlier this fall, human trials began at WRAIR, where 75 healthy adults were vaccinated with the Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine. The technology used to create the vaccine mirrors the process WRAIR undertook to produce its Japanese encephalitis vaccine, which was licensed in 2009.

"We have a lot of really young Soldiers here at WRAIR, and this will be the most unusual assignment they will ever have in the Army because we are not a troop unit," said Col. Nelson Michael, director of WRAIR's Military HIV Research Program and Zika program co-lead. "We're not a hospital unit, either. We're something else ... They come here, and they are exposed to science."

Both Michael's and Springer's laboratories are just a small sliver of an institute of 2,000 personnel, many of whom work in far-flung locations in Africa and Asia, Michael said.

"[For the Soldiers,] WRAIR is basically a combination between being at the Army University and an Army company," Michael said. "We don't do basic science for its own sake. We do a lot of very good basic science, but we do it always so we can eventually propel a scientific discovery into the field, something that protects Soldiers."

WRAIR's in-house capabilities are credited with enabling scientists to quickly develop a vaccine. The Pilot Bioproduction Facility, led by Dr. Kenneth Eckels, manufactures small doses of the vaccine to be used in clinical studies.

ZIKA'S EMERGENCE

Zika was first identified in Uganda in 1947. In recent years, researchers who tracked the Zika infection through WRAIR laboratories in Thailand realized the infectious disease was beginning to emerge, Michael said.

"Much like Ebola was an epidemic of disease as well as an epidemic of fear, Zika is an epidemic of disease as well as an epidemic of fear," Michael said. "Zika is new and frightening [to the public], especially if you are about to become pregnant or you are pregnant."

As of Nov. 30, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 156 cases of Zika infection were confirmed in the military health system, including cases among four pregnant service members and one pregnant Family member.

The CDC recommends that women and men who are returning from Zika-affected areas abstain from sex or use condoms for six months, an increase over the previously recommended eight weeks.

"There has been at least one documented case of a Soldier who was infected with Zika overseas, came home, had sex with his wife and transmitted it," Michael said. "Zika has some twists to it -- [such as] the fact that it can be transmitted sexually, because usually when you think of a disease that was borne by mosquitoes you think, 'Make sure you don't get bitten by a mosquito.' Now, you have got to be thinking about something else."

Though the disease has been around a long time, scientists knew little about it until very recently, Michael said. Infection during pregnancy has been found to cause birth defects, with one infected person in 4,000 developing a serious complication called transverse myelitis, or Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

"Basically what it means is your muscles stop working, your sensations stop working, and it comes up in your lower extremities," Michael said. "If it goes high enough, you stop breathing."

"For all these reasons," he added, "sexual transmission, the rare but finite chance of a developing neurological disease if you are an adult, and the fact that we don't have a vaccine for it -- this is why we all jumped on it."

COLLABORATION COUNTS

Progress on a vaccine was rapid once Michael and his WRAIR colleagues -- now-retired Col. Stephen Thomas, an infectious disease physician and a vaccinologist specializing in flaviviruses, and Dr. Kenneth Eckels, who runs the Pilot Bioproduction Facility -- banded together. Thomas is the former deputy commander for operations at WRAIR and the former Zika program lead.

In March, Michael received a phone call from Dr. Dan Barouch, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Barouch's center was developing mouse and monkey models to test the Zika vaccine but did not have a vaccine to test. Michael's team had made a vaccine but did not have the mouse and monkey models to test it.

A deal was struck, and a couple of weeks later WRAIR shipped Barouch the vaccine. Soon after, researchers proved that the vaccine protected mice and monkeys who were exposed. The usual timeframe for transitioning from the development of a vaccine to human studies is about four years, Michael said. They did it in 200 days.

"We all put it together, and everyone shared," Michael said. "No one tried to compete with each other."

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

With the advent of WRAIR's vaccine came the national spotlight, which has highlighted the research institute and its scientists' work on Zika. Two of their reports on the Zika Vaccine Program were published in Science and Nature journals. An article in New Yorker magazine followed, as well as many others.

"If you're a young sergeant [like Springer] and you're watching this happen, this is pretty amazing," Michael said. "Zika is probably the most topical infectious disease of 2016. People are talking about it all the time, and here he is: sitting in this environment, watching it happen. He is the tip of the spear. That's what we do here."

Because of his work in the lab, Springer has participated in the kinds of media interviews that young NCOs rarely handle. Though he has thrived on the intensity of working on such a critical project and has enjoyed seeing his name in print, Springer is now ready to move on to other projects at the institute.

"I hope everything goes well in human trials and the vaccine successfully gets distributed," Springer said. "I hope I don't have to do any more work on Zika -- that's what I hope more than anything. ... I am ready to be done with it. I want that virus to be extinct."

Though the World Health Organization announced recently that Zika is no longer a world health emergency, WRAIR officials say the fight to limit its spread and prevent a future outbreak will continue. WRAIR is focused on supporting the readiness of a force whose service members are deployed around the world.

Licensing the Army's vaccine for commercial use could take about two years if human testing proves to be successful, he said.

"If our vaccine works, it's the one the Army would buy and use," he explained. "Even though I have a dog in the fight, I really don't care which dog wins. I just want to have a tool that protects Soldiers."

Social Sharing