Editor's Note: The Pentagram prints work by published writer and JBM-HH Commander Col. Patrick Duggan. This is the first in a two-part feature written originally for Small Wars Journal, reprinted with permission here. Small Wars Journal is a professional medium that uses contributed content from serious voices across the small wars community to "help fuel timely, thoughtful, and unvarnished discussion of the diverse and complex issues inherent in small wars," according to SWJ editorial policy. For the original, cited work, see http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/to-operationalize-cyber-humanize-the-design.

Cyberspace…the military riddle of the modern age. Despite well-intentioned talk across the U.S. Army to "operationalize cyber," the indispensable means for doing so, is to "humanize" the design. Conventional U.S. Army wisdom proclaims cyber a "war fighting domain," and its networks the war-fighting platform.

However, the problem with this linear logic is, where do humans fit? This article asserts the need to expand the discussion about operational cyber, and challenges the convenience of simply wedging offensive and defensive notions into an artificial domain. Instead, it advocates an accelerated cycle of learning and sharing, to build enterprise trust and humanize the design.

Operationalizing cyber is not about linear thinking and lines of operation; it is about building trust in a process that speeds the cycle of individual education and branch collaboration. Humanizing cyber requires every Soldier to become cyber-aware and every branch to adapt cyber to its own distinctive cultures, missions and needs. The days of relegating cyber-thinking to communication and intelligence communities are over. Cyber is a team event now, and requires as much creativity, diversity and proliferation as the U.S. Army can muster.

In 1978, renowned American computer scientist, economist, political scientist, psychologist, painter, pianist and one of the most original thinkers of the 20th Century, the late Dr. Herbert Simon, was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to the field of economics.

A quintessential polymath, Herbert Simon was an early pioneer in numerous fields of study, and in his lifetime, contributed many new theories, organizing principles and ways to ponder a world rapidly inundating with information, computers and technology. Simon was ahead of his time, exploring cyberspace before the word was coined, and even co-authoring the first publication on artificial intelligence in 1956, long before the field was created.

However, what makes Herbert Simon so singularly unique, was his unshakable focus on the centrality of humans, their decisions and interactions in whatever field he examined.

Exploring how organizations, businesses and government agencies could best operate in an "information-rich" 1971 world, Simon asserted that true progress comes not from building ever-more powerful technology, but by humanity's ability to conceive better designs as they conjointly evolved.

Meaning, despite today's fixation on connectivity and cognification of inert things, we must never forget about humans in cyber's design.

So, as cyberspace emerges as the military riddle of the modern age, the true implication of the riddle is, what do humans do about ourselves?

U.S. Army Branch examples. In less than a decade, Special Forces (SF) Battalions will deploy to remote and austere locations where there will be no power and all military communications will be jammed. SF teams will employ their own conceptualized cyber-enabled Unconventional Warfare (UW) tactics, like using adhoc wireless meshed networks for communication with their local surrogate partners.

These indigenous-compatible, multi-protocol mesh, will be solar-powered and encrypted, and ride Rasberry Pi nodes run on hastily written Python code. Cyber-enabled UW networks will relay voice and data in near-time, and enable SF Soldiers wearing augmented reality goggles to call fire support for their indigenous partners miles away.

Nearby, there will be an Infantry Division fighting to establish a foothold in a sprawling cyber-contested urban environment. Infantry companies will employ their own conceptualized cyber-enabled Movement to Contact tactics, like enroute rolling pen-tests to probe local and wireless networks, and in-extremis exploitation of the sector's Internet of Things (IoT). Along their advance, cyber-enabled Infantry tactics will decrease the probability of enemy ambush and enable the companies to make contact with the smallest element possible, so that they can fix, maneuver and relay calls for fire to micro-drones hovering in support.

Just off the coast, there will be hundreds of armored vehicles, tanks and cargo stuck floating on transport ships. In the port, a Logistics Battalion will be scrambling to remediate malware and localize cyber-attacks against dilapidated industrial controls and SCADA devices. Inside the city, there will be cyber-linguists advising and assisting the host nation on methods to counter cyber-attacks against the country's remaining critical infrastructure.

All the while, cyber-operators will be scripting and translating open-source code while remaining sensitive to the culture.

So what? This scenario is one the U.S. Army could soon face, and one for which every Soldier and branch must be prepared. But what is the thinking to get it there, more importantly, a design to prepare?

The argument. In Martin C. Libicki's seminal paper, Cyberspace is Not a Warfighting Domain, Libicki correctly argues that cyberspace should not be confined to a warfighting domain, and that doing so, "is misleading, perhaps even pernicious." While understandably expedient for militaries to train, organize and equip Soldiers around, the danger of treating cyber as a military domain is that it incorrectly imposes artificial boundaries around an abstraction that simply do not exist. While military cyber-doctrine is rife with curated categories, the truth is cyber operations are based on intent, thus require context and perspective. In reality, cyber-operations are extremely difficult to label, as some of the same tools, methods and architecture used for defense can also be employed for offense. Traditional Westphalian notions of territorial integrity and sovereign authority have limited value due to cyber's ambiguous nature.

No single entity owns cyberspace. While every physical component of cyberspace may be owned individually, as a whole, cyber is not owned or controlled by any single nation, individual or organization. With 90 percent of the world's Internet owned by the private or commercial sectors, no single military has the capability or capacity to secure the entire space, or even a mandate to try. Further, there are countless other ephemeral networks and dynamic typologies which come and go daily, along with over 5.5 million new things being connected to the IoT every day. In fact, the entirety of cyber infrastructure is a hodgepodge of public and private networks lacking standardized security or access controls, which spawn incessant vulnerabilities and breed situations for more.

Military terms and concepts shouldn't be forced. Labeling the unknowns of cyberspace with familiar military terms may be comforting, but it pre-emptively hobbles human creativity. Wedging military jargon like key terrain, cyber-superiority and network liberation into an essentially non-military space is an intellectual easy way out.

Military terminology cannot convey cyber's true character and complexity, and it simply encourages refashioning the ambiguous and unclear into the familiar and trite. Proclaiming cyber a military domain undermines its expansive private nature, infers accepted limits and conveys the dangerous preconception of shared martial norms with potential enemies. Ultimately, viewing cyber as a warfighting domain undermines its true nature and undercuts the critical thinking of humans in the design.

Modern militaries have incorporated operational design into campaigns, strategies and battles since the days of Carl von Clausewitz. Interior and exterior lines, lines of operation, lines of effort and logical lines of operation are all linear in nature, and have served to arrange and link spatial, temporal and physical objectives to a greater purpose or a grand design. According to Army Doctrine Reference Publication 3.0, lines of operations and lines of effort link objectives to an end state, and commanders may use one or both to describe the operational design. In short, linear designs and thinking have dominated Western military thought for hundreds of years and continue to pervade.

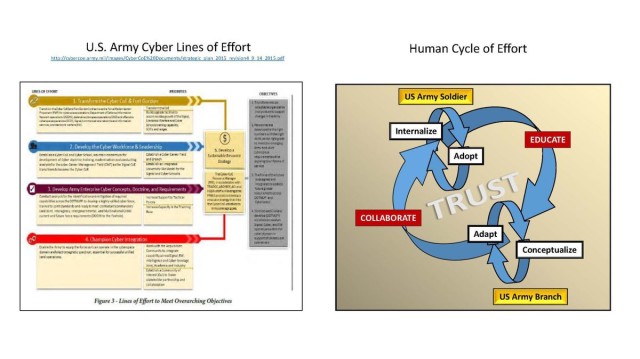

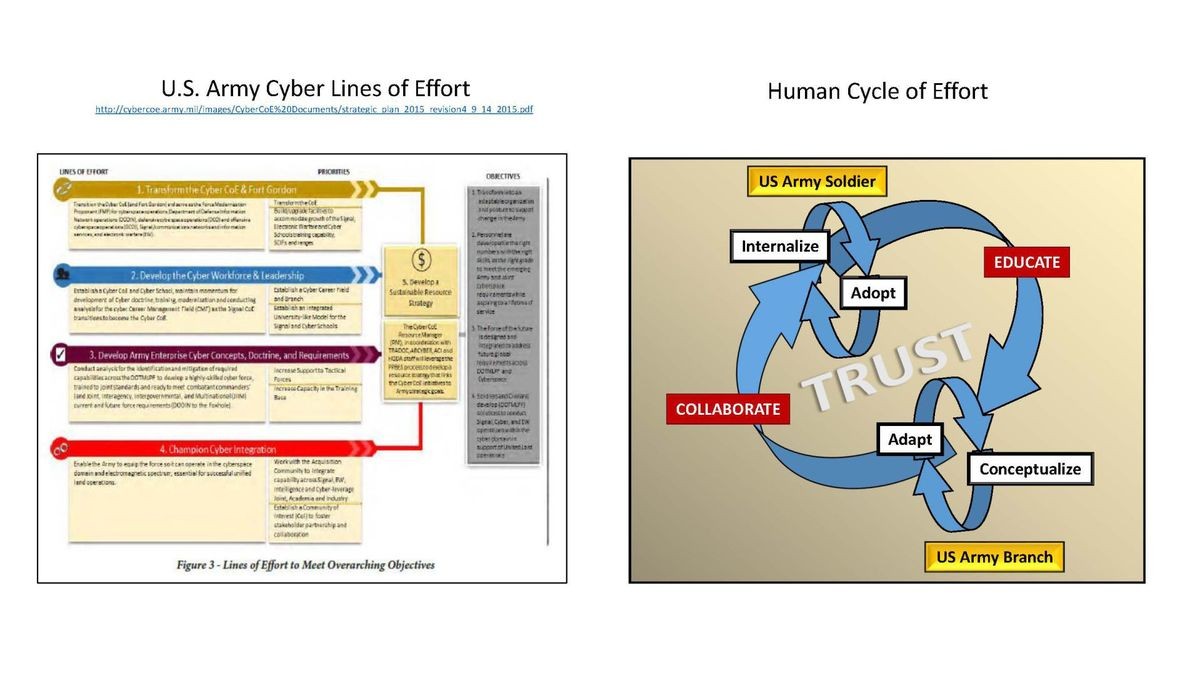

While the value of linear design to military operational art is well beyond the scope of this paper, this paper does advance an unorthodox approach to operationalize cyber. Figure 1 depicts an example of traditional lines of effort, as reflected in the U.S. Army Cyber Center of Excellence's 2015 Strategic Plan. Figure 2 depicts a non-traditional approach that iteratively emphasizes humans in the design.

The real contrast between the two is not in their specific objectives, but in their orientation, as Figure 2 emphasizes the centrality of humans in continuous cycles of effort. Humanizing cyber requires the acceleration of every single Soldier's cyber-education and the velocity of every branch's collaboration. Individually, Soldiers must internalize and adopt cyber in their daily lives.

Organizationally, every branch must develop its own concepts and adapt cyber to suit its distinctive cultures, missions, and needs. Ultimately, an iterative human design builds enterprise-wide trust and pushes cyber to the heart of soldier identity--themselves as individuals and themselves as an organizational branch.

Next week To Operationalize Cyber, Humanize the Design: Every Soldier Cyber-Aware, part 2 of 2.

Related Links:

To Operationalize Cyber, Humanize the Design: Every Soldier Cyber-Aware

Social Sharing