How the history of the U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command (AMCOM) relates to the Army's last pack mule units is an interesting story, traceable to the rapidly changing military technology being developed and deployed at the height of the Cold War.

While missiles and helicopters are recognized as the handiwork of human ingenuity, the mule's existence as a specially designed tool is often overlooked. Bred for bearing heavy burdens somewhere in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) sometime between 4,000 and 3,000 B.C., mules are hybrids that do not exist in nature.

They are the offspring of the deliberate pairing of a male donkey and a female horse. Because of an odd number of chromosomes the animals are usually infertile, so continual human intervention is normally required to increase existing barrens of mules. American mule breeding began in the 18th century with George Washington, former commander of the Continental Army and first president of the United States, who wanted to produce stronger animals suited to plantation work.

The U.S. Army first used large numbers of mules in the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). During the Civil War, the Union Army employed about 1 million mules to transport artillery and pull supply wagons. The Quartermaster Corps purchased the animals from various dealers. Confederate access to the animals was more limited and most mules were supplied by individual soldiers or confiscated from southern farms.

Although familiar with mules from his experience in fighting Indians before the Civil War, it was not until he became Commander of the Department of Arizona in 1871 that Maj. Gen. George R. Crook revolutionized the Army's use of mules as pack animals. Famed as a Civil War commander and later renowned as an Indian fighter who respected his elusive enemy, Crook was, according to Richard E. Killblane, "a maneuver commander who understood logistics." As such, he took a scientific approach to improving the use and organization of pack mules to enhance the cavalry's mobility.

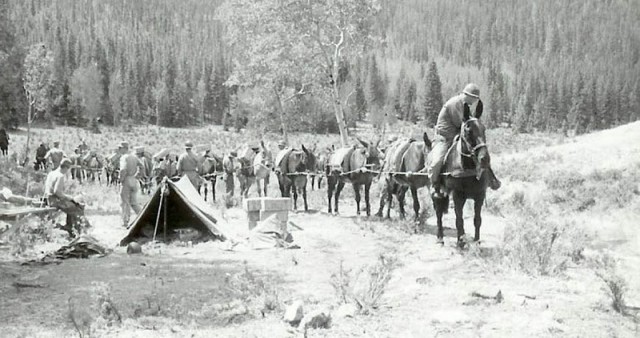

Custom-fitted packs for each mule, carrying only mission-essential items, doubled the pack mule's load to 400 pounds. Carefully reorganized pack trains and highly-qualified mule skinners created a standardized, very reliable and quick method of transport. While mule-drawn wagons continued to stock the supply base, specially-organized pack trains accompanied combat operations, allowing numerous small patrols to continually pursue the highly-mobile mounted Native Americans of the Plains and Southwest. "By the end of the 1870s, the pack mule had become an integral part of the U.S. Army."

Subsequently, mules served overseas with the Army in every war from the Spanish-American War of 1898 through World War II. Better adapted to steep mountainous terrain and dense jungle trails inaccessible to more conventional transportation, pack mules carried food, supplies and ammunition into distant battle zones and often carried out wounded soldiers.

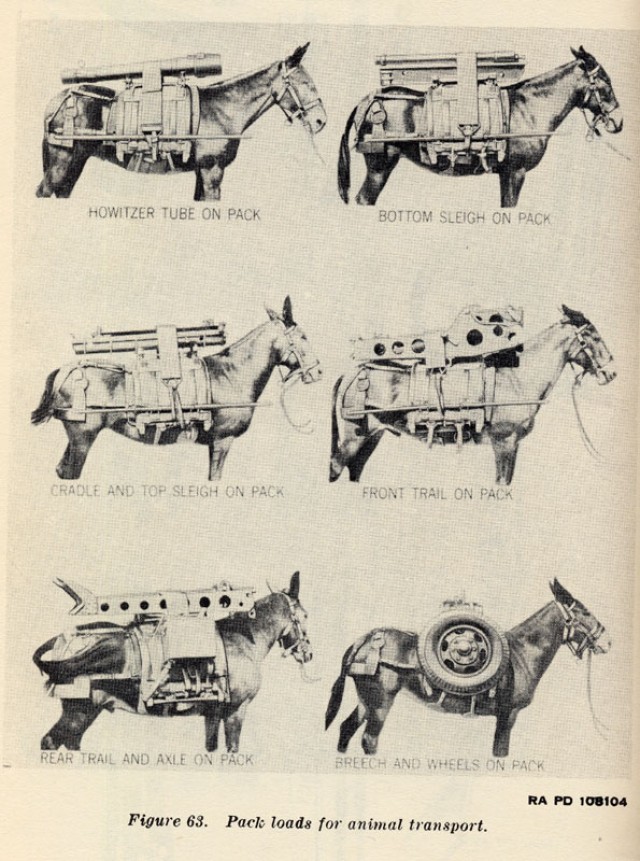

One valuable pack mule contribution to the Army's Field Artillery units was the animal's ability to carry disassembled weaponry. The U.S. Army had made use of animal transport to move artillery since the 1830s, but the adoption of the 75mm Pack Howitzer made available to Army commanders in World War II an adaptable and effective light artillery weapon system specifically designed to be moved easily across challenging terrain. Designed in the aftermath of World War I, this artillery piece could be broken down into six major components, each carried by one mule.

By the time North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel on June 25, 1950, however, the Army's reliance on pack mules began to diminish as trucks and helicopters assumed the burdens once loaded on the backs of animals. The growing reliability and survivability of Army Aviation's rotary-wing aircraft in particular made possible the more rapid movement of Soldiers and supplies over rough ground. The added benefits of faster MEDEVAC operations also contributed to the obsolescence of the Army pack mule.

In 1952, Maj. Lee O. Hill, chief of the Quartermaster Corps' Remount Branch, revealed in an article that "Contrary to general belief there still exists in the military establishment a remnant of animal activity…. Horses and mules are being used to a limited extent…, largely for mounted guard duty, policing at posts and stations, and for ceremonial purposes at military funerals." He also noted that two pack units stationed at Camp Carson, Colorado, remained on active duty as a training base in case the pack service needed to be expanded.

Another newspaper report in 1955 disclosed, "The Chicago army recruiting station has received a generous response to a call for volunteer mule skinners … to serve in the two remaining animal units in the regular army…. Enlistees were given the choice of belonging to the 4th field artillery or the 35th quartermaster company…. The mules are used only in Camp Carson, Colorado." But escalating Cold War tensions and an accompanying focus on more advanced technological innovations finally brought an end to the Army's 85-year-old reliance on the standardized use of pack mules.

Field artillery was a venerable arm of the U.S. Army by the mid-1950s. As explained by Janice McKenney in her 2007 study, The Organizational History of Field Artillery, 1775-2003, "The term artillery originally referred to all engines of war designed to discharge missiles, such as the catapult, ballista, and trebuchet, among others. Toward the end of the Middle Ages,… artillery came to mean all firearms not carried and used by hand. By the mid-twentieth century, it included all manner of large guns, howitzers, rockets, and guided missiles…." The addition of "field" to the original designation denoted only mobile artillery which could move with an army as needed.

During the second half of the 20th century, the Army's Field Artillery organization and doctrine underwent numerous changes as a result of rapid technological advances in the evolving field of rocketry and missilery. While the basic principles of rocket propulsion were first demonstrated in 5th-century B.C. Greece, the first true rockets were the "fire arrows" used by the Chinese against Mongol invaders in 1232. Various armies continued to make limited use of such weapons for the next 600 years, including the British during the War of 1812 and the U.S. Army in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848. But it was not until the introduction of the German V-1 and V-2 rockets in World War II that more intense interest in the application of rockets and guided missiles to the modern battlefield occurred.

Despite a special demonstration by Dr. Robert H. Goddard for Army officials in November 1918, the Army Ordnance Corps did not establish its Rocket Development Branch until September 1943 to direct and coordinate the Army's efforts in this new field of weaponry. The first of the Army's integrated missile programs planned to progress from test vehicle to guided missile was the Ordnance-California Institute of Technology (ORDCIT) project established in May 1944. Later, in November of that same year, Army Ordnance awarded a prime contract to the General Electric (GE) Company for Project Hermes, another ballistic missile research and development program. The Army amended the Hermes contract's scope of work the following month to include the study of the German V-2 rocket.

As part of Operation Paperclip initiated in 1945 during the final months of the war in Europe, the Army succeeded in relocating "the cream of the crop" in German missile scientists and engineers to Fort Bliss, Texas. Once their transfer was complete, Ordnance Corps senior leaders believed the team of specialists headed by Dr. Wernher von Braun would help to build the foundation for the service's emerging guided missile program.

Because of the increasingly obvious fragmentation of the Army's research and development activities in the new technology, the Chief of Ordnance selected Redstone Arsenal in October 1948 to be the site of a new center charged with the primary mission of conducting basic research on rockets and related systems. A subsequent facilities survey undertaken by representatives of the Research and Development Division Sub-office (Rocket), Fort Bliss in September 1949 resulted in official approval by the Secretary of the Army on October 28, 1949 to move the Sub-office (Rocket) to Redstone Arsenal.

A total of 500 soldiers, 100 "top" Germans, and 65 DA civilians were relocated to north Alabama beginning early in April 1950. With the arrival of the "Fort Bliss group," the arsenal was charged with research and development of guided missiles in addition to basic and applied research, development, and testing of free rockets, solid propellants, jatos, and related items. One year later it assumed responsibility for the national procurement and field service missions.

Also in 1950, the Army Chief of Staff established the Army Equipment Board to review the service's equipment needs. Headed by Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge, the board reversed the immediate post-war emphasis on developing atomic bombs and strategic aircraft. The board revised the Army's guidance on research and development by stressing the importance of new field artillery weapons that would ensure the effectiveness of its ground forces against the growing Soviet threat.

Covered by the Hodge Board's guidance were the rockets and guided missiles eventually assigned to Redstone Arsenal. In response to these new requirements, personnel who worked for the missile commands headquartered at the installation oversaw the development of advanced weapon systems such as the Honest John rocket as well as the Corporal and Redstone guided missiles, all of which could carry a nuclear warhead. By 1954, the Army began deploying such systems in Europe to fill identified gaps in or extend the reach of Army Field Artillery support to the Soldier on the ground.

Effort on the missile eventually named for the arsenal where it was developed marks the point at which the history of the Army's newest and largest nuclear weapon of the 1950s became entwined with the history of the Field Artillery's last pack mule unit.

Early in the development stage of the Redstone missile program, military leaders and project team members "began making plans for the training of the soldiers who would field the weapon," wrote Edward A. Herron in an August 1958 special report for Rocketdyne, the rocket engine contractor on the Redstone project. "This was the Army's biggest and most complicated weapon system--and there were no troops available with the required training and experience." In 1956, several significant actions occurred which shaped the Field Artillery units associated with the Redstone.

First, in February 1956, the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) stood up at Redstone Arsenal. It was responsible for developing the Jupiter Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile and continuing the Redstone missile project. Ordnance assigned oversight of the Pershing missile program to the command in 1958. But it was the agency's widely-publicized contributions to the nation's early space exploration program that brought the arsenal lasting fame and made it home to the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, the only NASA facility of that type collocated with the Army.

Next, the Army activated the first Redstone unit--the 217th Field Artillery Missile Battalion, Redstone--at the arsenal in April 1956. According to Herron's special report, "When the soldiers appeared at the Arsenal, they were a hand-picked group, career men of the regular Army with proven aptitudes and interest for this new endeavor. A high percentage of the NCOs were the veterans of U.S. and overseas service with the smaller Corporal missile, pulled back to utilize their skills on the 'big one'."

Because of the Redstone's unique characteristics and capabilities, ABMA rocket scientists and contractor support personnel worked directly with 217th personnel during their training at the Ordnance Guided Missile School on post. Problems with how the battalion was structured initially, however, led to its reorganization in September 1957.

Finally, a major component of the future 40th Field Artillery Missile Group (Heavy) became available for reassignment on December 15, 1956 at Camp Carson when the Army deactivated its last two mule pack units. Over 300 mules were sold or transferred to other federal agencies, such as the Forest Service and the National Park Service.

However, the Army reactivated Battery A of the 4th Field Artillery Battalion (Pack) the following year as part of the Redstone missile group in Alabama. By June 1958, the former mulemen had deployed to Germany as Redstone missilemen. "Less than 18 months before this same outfit had seen the last of 200 [sic] mules retired from the rolls; today the group rides herd on the most powerful weapon in the United States Army."

Both the Redstone missile and the 40th Field Artillery Missile Group achieved numerous Army "firsts" between 1956 and 1964. In its tactical configuration, the Redstone became the first operational, prototype long range ballistic missile to be fired in the western hemisphere when it flew to a range of over 400 nautical miles in December 1956. Recalled Maj. Gen. John B. Zierdt, head of the Army Missile Command, in a speech about the Redstone given in November 1964,

It was the first large ballistic missile developed in this country to reach operational status, the first to be fired by soldiers, the first to join U.S. Army units serving overseas in defense of freedom.

Redstone gave the Army our first experience with mobile, long range missiles. The impact of that experience on Army tactics and organization--indeed on the entire future of land warfare--more than justified the investment made by the American taxpayers in the Redstone system.

The first object fired over an intercontinental range was launched by a Redstone.

The first man-made object flown into space and recovered intact was launched by a Redstone.

The first missile deemed reliable enough to carry and detonate a nuclear device was a Redstone.

Our first scientific Earth satellite was launched into orbit by a Redstone.

Our first astronaut rode a Redstone….

Its contributions to the advancement of rocket technology are equally impressive. All the major areas of rocketry--such as propulsion, guidance and control, electronics, and materials--were advanced during the Redstone's development.

The 40th Field Artillery Missile Group was the first heavy missile group organized in U.S. history. In addition, unit members were the first troops to launch a Redstone at Cape Canaveral, Florida, on May 16, 1958. A little over two weeks later, when the 40th launched a Redstone at White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, on June 2, 1958, they successfully fired the first American ballistic missile over land. The group also was the first Redstone unit to deploy overseas.

Long a symbol of the U.S. Army and still the mascot of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the mule's name, unlike the Redstone, has never really been erased from the service's vocabulary. Interestingly, although it replaced the animals, the Army retained the "mule" name for use in connection with some of its newer technology.

In 1953, for example, the Army inventory included 63 Piasecki H-25A light cargo/utility helicopters, commonly known as the Army Mule. The tandem rotor, single engine rotary-wing aircraft influenced the designs of the later H-21 Shawnee and AMCOM supported CH-47 Chinook helicopters.

The multifunctional utility/logistical equipment vehicle, better known as the M274 Mechanical Mule, was a specialized small platform vehicle capable of moving supplies and troops over rough ground. Introduced in the mid-1950s, the versatile Mechanical Mule was favored by Soldiers and Marines in Vietnam. Designed to keep pace with infantry units, it also served as a suitable launch platform for the TOW missile.

In addition, the modular universal laser equipment (MULE) was a portable device used to target laser-seeking tactical weapons. It was used primarily by the Marine Corps. The latter branch of the U.S. armed forces, though, has never given up its use of pack animals, particularly mules. Consequently, the Corps maintains the only pack animal training facility for the entire U.S. military. Special Forces training in the use of pack animals resumed more extensively in the wake of operations in challenging environments such as those encountered most recently in Afghanistan.

The L.A. Times reported in July 2009, the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center in California offered a twelve-day course, eight times a year to its own service members, Army Soldiers, Navy SEALS and some foreign troops. Trainees were taught "to pack machine guns, mortars, grenades, Javelin missiles and M-16 ammunition, as well as food, water and medical supplies--all needed to carry the fight to the enemy."

The motto of the 4th Field Artillery (Pack) before it exchanged its mules for missiles was Nulli Vestigia Retrorsum, meaning "No Step Backward," a reference to the surefootedness of the Army mule. In Army Field Manual, FM 3-05.213, "Special Forces Use of Pack Animals," issued on June 16, 2004, the service acknowledged its error in completely dropping the use of pack animals.

Thus in the opening decades of the 21st century, the mule has come full circle, vindicated as a still essential tool among the high-tech weapons being used to meet the ever-changing demands of modern warfare and the current threats to the nation's security.

Social Sharing