If Dec. 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, is a day that has lived in infamy for 75 years, the day after, Dec. 8, 1941, has been all but forgotten. Forgotten, that is, by everyone but the men and women who endured a second wave of attacks against the United States, this time in the Philippines, and would spend the next four years in a desperate battle for survival.

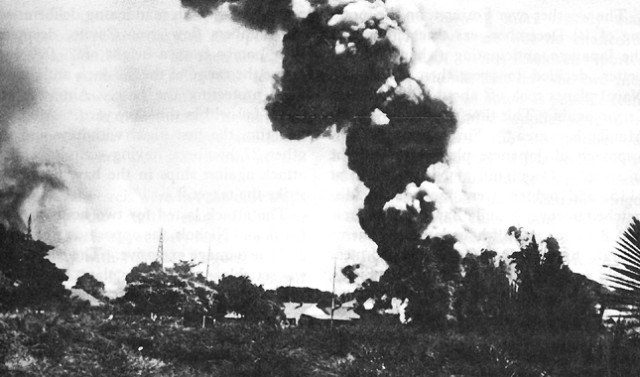

News of the bombings in Hawaii had crossed the International Date Line and reached the Philippines at about 2:30 a.m., Dec. 8. By 8:30 a.m., some small Army camps in the north of the country were under attack. By 12:30 p.m., the Japanese were dropping bombs on the main U.S. bases, especially the Philippines' five major airfields.

At the very least, the U.S. military should have had enough time to save the brand-new fleet of P-40 fighters and B-17 bombers on the archipelago. But commanders in the Philippines were scrambling. Orders had been countermanded. Pilots had been told to stand by. Some managed to get airborne, but most of the planes were destroyed.

"It was very shocking," remembered former Pvt. Dan Crowley of the Army Air Corps, who was having a cup of coffee when the bombs began to drop on Nichols Field. "You had about 100 of these aircraft, almost totally unopposed, flying back and forth, firing, strafing, bombing at will. They destroyed all the infrastructure of the airfield, the hangars, the bomb supplies, the machine shops, the fuel dumps -- everything was wiped out in one blow.

"They had assigned me to a so-called anti-aircraft machine gun that was a vintage World War I model Lewis gun. It had 90-round magazines sitting on top, and it would jam easily."

According to William Donnelly, a World War II expert at the U.S. Army Center of Military History, people have been pointing fingers ever since:

"Various writers and historians have weighed in, picking villains, saying this person is most responsible. … They did have eight or nine hours before the Japanese … started the attack. … Even without radar, you should have started dispersing and putting up combat air patrols."

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

The Philippines had been ceded to the U.S. by Spain after the Spanish-American War, and the islands were on track to achieve independence by 1946. At some 7,000 miles from San Francisco, the Philippines were simply too far away for the U.S. to garrison or protect adequately, while they lay at the center of a vital shipping lane between Japan and Indonesia.

According to Donnelly, planners in the War Department had always known the U.S. could never hold them against a Japanese invasion. As early as the 1920s, they developed War Plan Orange. It called for a retreat to a finger of land on Luzon, the largest of the Philippines' 7,000-odd islands, known as the Bataan Peninsula, and Corregidor, a tiny island fortress off its tip. Stockpiles of food and ammunition would allow them to hold out until the Navy could arrive.

MacArthur, by contrast, believed American air power would save the islands and defeat a Japanese invasion. Under the new Rainbow Plan, he positioned his forces along the beaches where the Japanese were most likely to land and redistributed all of those supplies across Luzon -- just in time for Japan to destroy U.S. airpower in the Philippines. The new plan would be useless.

"The Japanese now can use their air units to roam across the islands and attack the Americans and their lines of supply," Donnelly said. "Most importantly, losing air superiority over the islands means that there's no way for the Navy to safely bring in reinforcements and resupply.

"Without air power, they can't defeat the invasion force or contain it, which means they have to revert back to War Plan Orange … but by then, they have dispersed their supplies."

ALLIED FORCES

In addition to the Philippine army, which Gen. Douglas MacArthur had been building before he was recalled to active duty, U.S. Army units included many Filipino soldiers and scouts -- about 22,000 -- in addition to American officers and largely untrained and untested enlisted men.

After the U.S. began to mobilize, a number of new units arrived in the Philippines in 1941, including two anti-aircraft units from the New Mexico National Guard, the 200th and 515th Coastal Artillery regiments, bringing the garrison total to about 32,000 American men by Dec. 1.

"A large number of the New Mexico National Guard Soldiers spoke Spanish," Capt. Gabriel Peterman, officer-in-charge of the New Mexico National Guard Museum, said of the assignment. "Their main defensive duty was [the] defense of Clark Field. They dug in and they had three-inch anti-aircraft guns. Their purpose was to defend against high and low-level air attacks.

"When Clark Field was attacked … they were the first to respond. … The problem is they were issued World War I ammunition and their fuses and their shells and their guns were unable to reach the Japanese planes."

Forces throughout the Philippines faced similar problems. Modern equipment and ammunition had started to arrive, but there wasn't enough of it to go around.

After a couple of weeks of intense bombing, and small landings throughout the islands, the main Japanese invasion force landed in northern Luzon, Dec. 22. Allied forces desperately tried to hold them off, but by Christmas, they were closing in on Manila, and MacArthur ordered the retreat to Bataan.

"Anyone who is clear-headed and thinking rationally will know that it's a forlorn hope," Donnelly said. "All they can do is hold out for as long as possible. … After the Japanese start landing on the 22nd of December, in Washington, they write off the Philippines."

DESPERATE CONDITIONS

The troops, who called themselves the "Battling Bastards of Bataan," were soon on half rations, and as supplies quickly dwindled, their portion sizes continued to decrease, supplemented by whatever they could find in the jungle.

His unit's cook, Crowley recalled, was a "magician with making due. He would find things to put in the soup pot that you wouldn't question because he made it taste good and it was something that filled your stomach. He was a master scavenger: snakes, monkeys, anything he could find for protein.

"It got to the point that there was nothing more to scavenge. We were in a state of slow but sure starvation. We were down to a skeleton-like state with the fat gone and the muscles withered."

And then there were the diseases: malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, beriberi, among others, in addition to combat wounds. The rudimentary, mostly open-air hospitals were staffed by talented doctors and nurses, but without adequate medicine, there wasn't much they could do for patients.

DOOMED

Still, the men fought and they fought hard, holding off an invasion that the Japanese expected to take weeks. The Americans, however, held them off for four months, from Christmas to Easter.

Only one regular Army infantry unit, the 31st Infantry Regiment, had been assigned to the island, and it covered the U.S. withdrawal, encountering some of the fiercest fighting on Bataan. For their parts, Air Corps Soldiers and Navy Sailors suddenly found themselves in the infantry, with no infantry training. But they learned quickly.

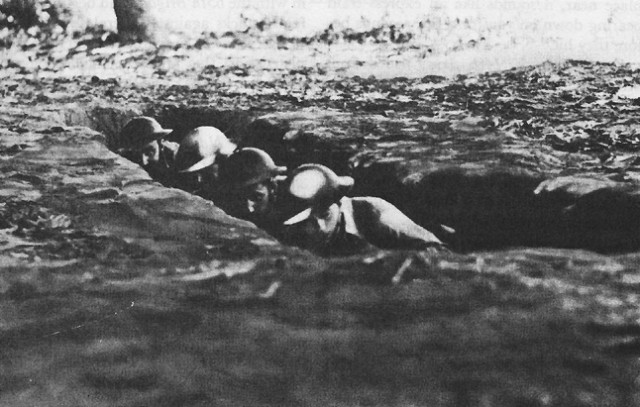

"We repulsed one large landing and there were several smaller ones," Crowley said, explaining that his new unit was called the Provisional Air Corps Infantry Regiment. "We were lined up along the shore. Our armorers … rigged [.50-caliber aircraft machine guns] so they could be cocked manually and be used as ground defense weapons.

"When the Japanese came in with that one attempt to land, it was estimated there were 60 barge loads of them. They were cut to pieces by these .50s. … On the right flank, we lined up with our Springfield rifles -- five shots with manual cocking with the bolt. The Japs that the .50s didn't get, we finished off with the rifles. These were the battles of the points."

The battle for Bataan was even the site of the last mounted cavalry charge in American military history, when 1st Lt. Edwin Ramsey led a contingent of Philippine Scouts from the 26th Cavalry Regiment against a Japanese force estimated to be 12 times his unit's size, actions for which he would receive a Silver Star. Sadly, the scouts' gallant steeds soon became dinner for the starving Soldiers.

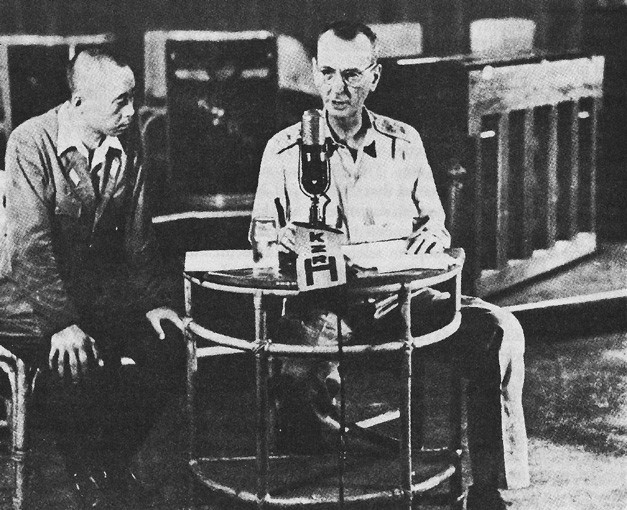

The Japanese kept pushing the American line back, ever closer to the tip of the peninsula. No help was coming, no reinforcements, no resupplies. After the enemy received fresh troops, Maj. Gen. Edward King was finally forced to surrender the largest number of Americans in history -- almost 80,000 -- April 9.

(King commanded forces on the peninsula after Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright took over for MacArthur, whom the Navy had spirited to Australia by submarine under orders from the president.)

Most of the Soldiers wanted to keep fighting, but King believed it would be suicide. Veterans today still insist that they didn't surrender -- they were surrendered.

"A lot of these guys felt ashamed that they had been surrendered," said Jan Thompson, the daughter of a Corregidor survivor, president of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society and documentary filmmaker about the period.

"None of them think they were heroes."

DEATH MARCHES

The Japanese force-marched American and Filipino soldiers some 60 miles to camps in northern Luzon like Cabanatuan and O'Donnell. While the most famous of these treks has gone down in infamy as the Bataan Death March, there was actually a series of bloody, brutal marches.

Conditions varied widely from Soldier to Soldier, from unit to unit, from location to location, but it was hell on Earth for almost everyone. Japanese commanders didn't make allowances for Soldiers who were already weak from malnutrition and various tropical diseases, or when men began collapsing from heat stroke and dehydration. Some were murdered outright. Others were left to die along the side of the road.

Enemy captors murdered Soldiers who tried to assist their fellow prisoners of war, and they killed Filipino civilians who tried to alleviate their suffering by offering food and water. And while there are reports of guards helping the prisoners, sharing their water, there are also reports of beheadings, of men buried and burned alive.

"I had no food for six days, very little water," former Staff Sgt. Henry Wilayto remembered in an oral history. "Finally, I passed out. They marched you early in the morning, sat you down about 11:00 a.m. and you'd stay in the field until 4:00 in the afternoon in the hot sun, 110 to 115 degrees, while the guards were in the shade.

"They killed, by bayoneting and shooting, about 650 Americans and I don't know how many Filipinos. It must have been in the neighborhood of 2,000 or 3,000."

The Japanese, he remembered, told POWs, "'You are not prisoners of war. You are captives. You surrendered. You did not fight. If you break our rules, we will kill you or we will do something worse.' They did something worse. We lost 23 men every 24 hours."

THE LAST HOLDOUTS

Not everyone had complied with the surrender order, however. Some Soldiers melted into the jungle and worked with the Filipino resistance to organize guerilla groups, including a number of the New Mexico Guardsmen and Ramsey, who commanded some 40,000 guerillas and would eventually be awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. Others, like Crowley, swam to Corregidor, where they continued to fight.

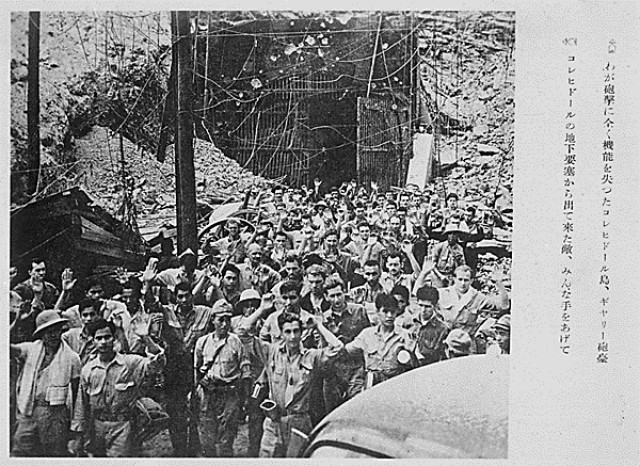

Corregidor was a fortress, heavily fortified with a network of tunnels that protected the hospital and the general staff from the constant Japanese bombardment. "The shells came in like the proverbial rain," remembered Crowley, who never made it into the tunnel and called the Soldiers who did "tunnel rats."

The situation became especially frightening when the Japanese brought in flame throwers. Then they landed a tank on the island. All it would have taken was one well-placed shot into the entrance of the main Malinta Tunnel and everyone inside would have been wiped out.

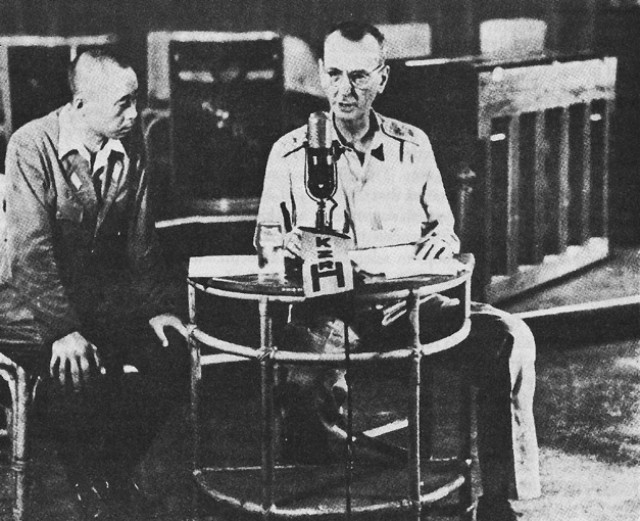

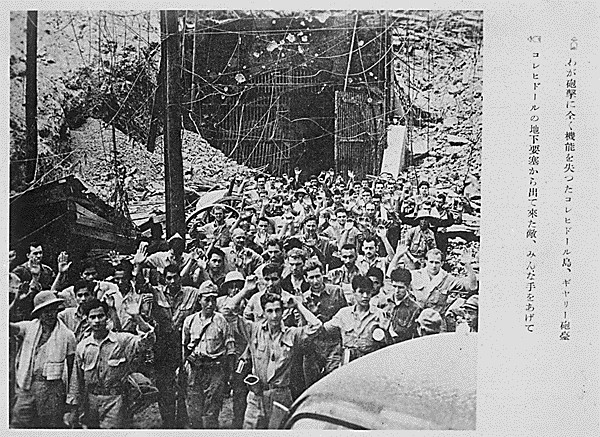

Wainwright knew it was hopeless. He initially tried to surrender only the forces still on Corregidor, but Japanese commanders insisted he surrender all remaining American troops in the Philippines, May 6. (There were still holdouts on other fortified islands.)

Then came "probably one of the worst experiences I've had," Crowley remembered. "Picture 12,000 starved, diseased people packed into this small area of concrete in this blazing sun. The Japs set up machine guns on three sides. The fourth side was the bay. There was nowhere you could go.

"I believe there was only one water pipe, one small diameter water pipe, about a half inch, and it was laid on the surface. The worst problem was the human waste. The ground was literally covered with it."

PRISONERS OF WAR

After several days, the American GIs were loaded onto boats and sent to Manila, where their captors paraded them through the streets before herding them onto blisteringly hot hell trains -- World War I-era 40-and-8 boxcars -- to the prison camps.

"You couldn't lie down, sit down," said Crowley. "We were packed together standing up. If you had to do your business, you did your business standing. The cars were covered with human waste. It was a horrible mess."

One of the many reasons American prisoners of war were subjected to such inhumane treatment, explained historians, was that the Japanese were not prepared for the number of prisoners they took on Bataan and then Corregidor.

"Part of their plan for moving the prisoners out of Bataan was to utilize captured American vehicles," said Peterman. "Well, Americans were under standing orders to destroy all of their equipment, so they put sand in crank cases, they punctured the gas tanks, they basically destroyed all of the equipment that was supposed to be used by the Japanese to move them to prisoner camps."

Of course, that doesn't explain the brutality -- and often sadism -- that Allied POWs encountered over the next three and a half years. It doesn't explain the starvation and the slave labor, or the beatings, the torture, the murders.

In fact, only about half of the men stationed in the Philippines in 1941 returned home after the war. The rest died in combat, succumbed to disease, starved to death or were worked to death, were executed by the enemy, or went to a watery grave when the U.S. Navy sank the unmarked hell ships used to transport POWs to China, Korea and Japan.

A BRAVE LEGACY

Those who lived wouldn't be liberated until 1945. That became the story of the Philippines: Outrage for those who had fallen in such terrible conditions. And pride in the determination, resistance -- most POWs sabotaged their captors in any way they could -- and resilience of those who survived in spite of everything.

The story behind their capture has been largely forgotten, however. "Americans don't like to surrender," said Peterman. "We're always the winners, so we don't like talking about our defeats. Even when we talk about the death march, we talk about, 'Oh, the Japanese were horrible, but our guys were able to overcome the atrocities in order to survive.'

"We shouldn't focus on the defeat as much as the incredible battle they fought. Those Soldiers held out for four months when the Japanese said, we'll be through with them in two weeks. Those Soldiers fought with no equipment, no food, no support for four months, slowing up the Japanese timetable for much of the Pacific as a result. That's a remarkable feat."

-----

To learn more about the POW experience, click on "Under the enemy's yoke: The POW experience in Japan" in the related links below.

Social Sharing