FORT SILL, Okla., Nov. 10, 2016 -- History can be ironic. Native American children in the early to mid-20th century were taken from their homes and taught in boarding schools which tried to erase all vestiges of their culture and language, and then a few years later it was their language that helped America win World War II. Irony, right?

Lawton's own Comanches were among the several tribes that contributed to the war effort by using their language as a code, one the Germans never broke. While the Navajo Code Talkers in the Pacific Theater were more well-known once the project became declassified in 1968 (see the "Wind Talkers" movie) the Comanche Soldiers used their skills from the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, through Victory in Europe Day.

Their exploits were written in detail, and with voluminous research, by William Meadows in his 2003 book, "The Comanche Code Talkers of World War II." The information in this article is taken from that book, and from the exhibit and website at the Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center in Lawton.

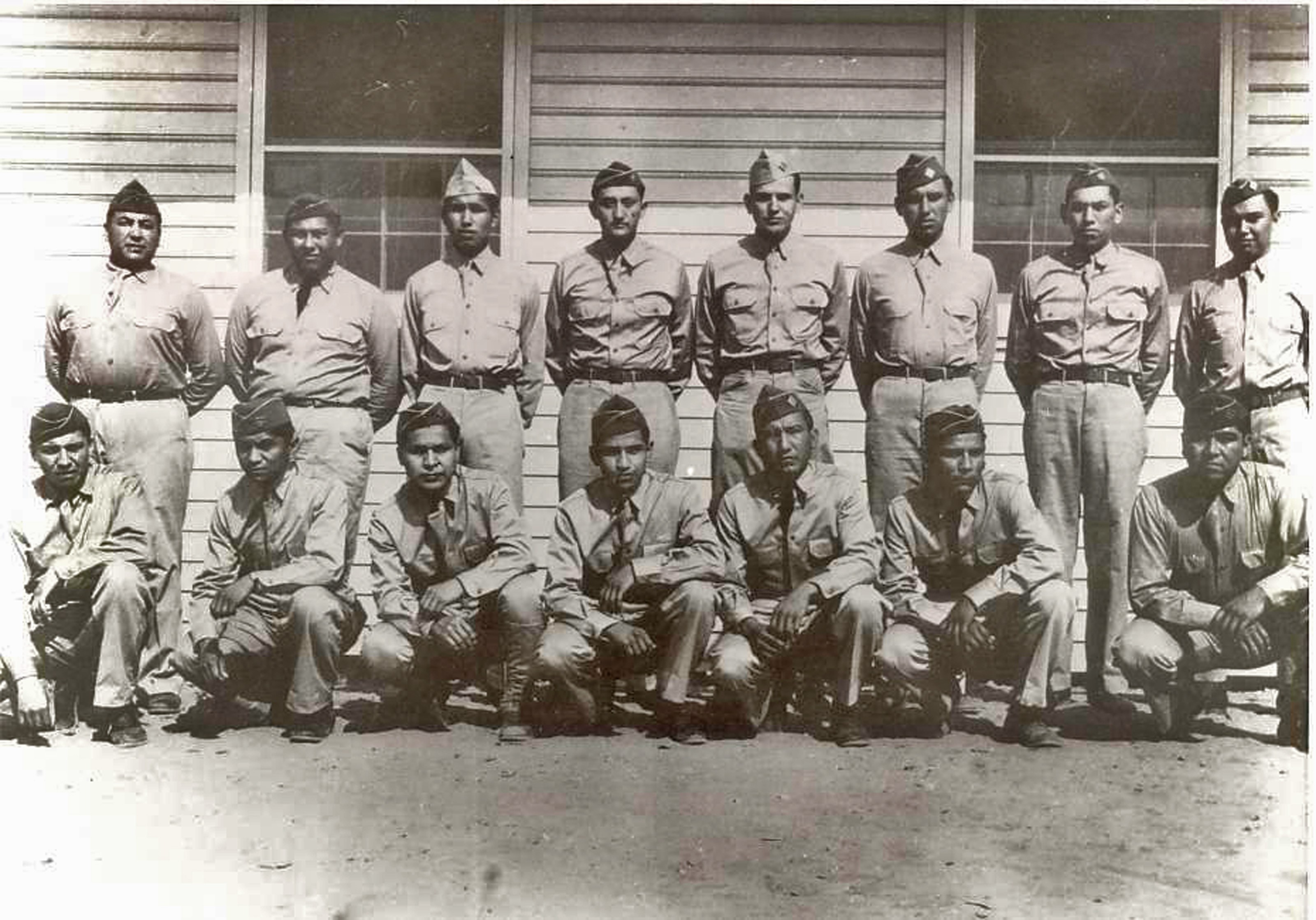

The 17 men who formed the Comanche Code Talkers weren't the first to be tasked with relaying messages in their native language during wartime.

Oklahoma's Choctaw was the first tribe used as code talkers during World War I, and a few news articles after the war were even written about the program. (So much for operational security.)

Prior to World War II Japanese and German "scholars" visited America to research Native American languages, including some who supposedly visited a German missionary church near Indiahoma in 1939. However, since Comanche wasn't recorded in ethnographic books, it was the ideal "secret" language.

Native Americans historically volunteered for military service at nearly twice that of the American population, according to the author. Tribal warrior traditions were often a young Indian man's way of proving himself, and since government-run boarding schools operated with the strict discipline and order of military schools, the transition into Army life wasn't that strange for the Comanches. As a matter of fact, the Code Talkers surprised their drill sergeant by how much they already knew, and their basic training was cut short because of it.

In addition to the language itself being a form of code to German eavesdroppers, the Comanches developed their own lingo of 250 code words to describe military and geographical terms for which there was no native word. For instance, bombers were "pregnant birds" and bombs were "baby birds." Tanks were "turtles," and Adolph Hitler was "crazy white man." Even other Comanches did not understand what these 250 words meant.

Apparently the program wasn't as secret as it should have been, as there were several newspaper articles written about the project.

The 4th Division (Motorized) publication even wrote, in 1942, "A dozen Comanche Indians from Oklahoma reported as a unit last December and January. Chosen primarily because the Comanche language is an unrecorded one and valuable for secret communication, the Comanches proved to be among the ablest men in the Company."

Although the Comanches trained as a group since their enlistment in December 1940 and January 1941, they were not combat-active until June 6, 1944 on the beaches of Normandy most of them at Utah Beach. (One of the 14 men was transferred to I-Corps because of his skill in cryptography, and three were discharged after training, leaving 13 to see combat.)

Code Talker Larry Saupitty was also the personal orderly, driver and radio operator to the division commanding general, Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. He sent the first Comanche language message when they landed 2,000 yards from their target. "We made a good landing," he spoke over the radio. "We landed at the wrong place."

The Code Talkers were distributed in pairs throughout the 4th Infantry Division (Motorized). The majority of their work was to lay and repair telephone wire, which was easily tapped by the Germans.

They also had to retrieve the wire as the troops advanced, and were trained with blindfolds to do splices in the dark. Although they had been in England for six months training for D-Day, some of the Code Talkers felt June 6 was just another exercise they'd been told was "the real thing."

Roderick Red Elk volunteered to string telephone wire high on a lone dead tree so it wouldn't get severed by tracked vehicles. He thought the artillery fire was simulated, as it had been in numerous exercises before. But once he saw German prisoners being escorted by American Soldiers, he realized the artillery fire was real. "Needless to say, I came down that pole in a hurry," he said.

Even though the government policy toward Indians was to remove every vestige of their culture as they became assimilated into the white world, the wars ironically helped invigorate Comanche traditions that were officially illegal. Warriors were seen off to battle and welcomed back home with dancing and feasting.

Returning World War I combat vets took part in "victory dances" and their mothers and sisters performed "scalp dances" so they were "ritually cleansed from the taint of combat by tribal medicine people."

The Comanche Homecoming was first held in July 1946 in Walters, Okla. to welcome home all the World War II tribal veterans. During the first Comanche Nation Fair held at Fort Sill's Eagle Park, Sept. 25, 1992, the surviving code talkers were honored. The tribe also dedicated the Army's Comanche helicopter.

Meadows writes that before going overseas many of the code talkers participated in a peyote ceremony in the Native American Church, and were given medicine bags containing a blessed peyote button to protect them. During difficult times, some of them consumed the peyote sacrament to help them through it. One of the code talkers, Haddon Codynah, said, "It must have worked, for all of us came back home."

They participated in many of the war's major events: the liberation of Paris, the Siegfried Line, Huertgen Forest, Battle of the Bulge, the liberation of concentration camps.

From June 6, 1944 to Germany's surrender May 8, 1945 the wire platoon of the Fourth Signal Company laid more than 15,000 miles of wire. Several Comanche Soldiers were wounded in action and awarded the Purple Heart and other medals.

As of the book's writing, fewer than 200 fluent Comanche speakers were left.

Social Sharing