The U.S. Army Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention (SHARP) Academy hosted a Professional Forum at Marshall Auditorium on Thursday, Oct. 27. The forum was entitled "Understanding the Neurobiology of a Sexual Assault Victim" and featured guest speaker Dr. James Hopper, an independent consultant and teaching associate in Psychology at Harvard Medical School.

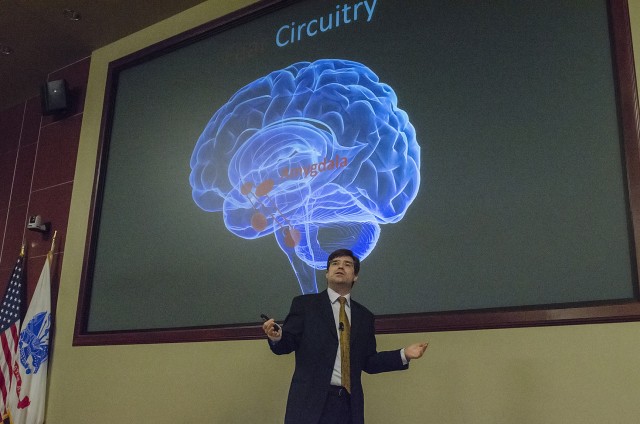

Hopper's focus at the forum was to inform attendees about what changes happen in a person's brain when they are being sexually assaulted.

"There are changes that happen in the brain when the fear circuitry takes over," Hopper said. "Understanding this is the key to understanding sexual assault, the victim's experience and how to investigate these crimes, as well as how to support victims in the aftermath."

According to Hopper and supporting research, when a person is being sexually assaulted -- as long as the person is conscious, even if intoxicated -- at some point the fear circuitry will detect the attack and immediately dominate brain functioning. Within seconds of the fear circuitry taking control, the prefrontal cortex is impaired.

"There is research going back decades on various species of animals on what happens to our brains when in situations of high stress," Hopper said. "We've found when a human or animal is under extreme stress, the pre-frontal cortex -- the rational part of the brain -- is significantly altered."

Another key aspect of Hoppers presentation was related to how key brain circuitries impacted by fear and trauma, effect the victim's memory of the assault. When the threat is perceived by the brain, memories may be extremely vivid. After an assault, a victim's memory may be fragmentary or they may not be able to put the time sequence together.

"Experiences around the time 'when the fear kicked in' are usually well encoded," Hopper said. "Attention is still required for encoding into memory, but because the hippocampus temporarily goes into a super‐encoding mode, memories of 'when the fear kicked in' may include substantial contextual and time‐sequence information.

"Details that did not get attention, likely because the fear circuitry didn't see them as relevant to survival, are usually not encoded into memory, or very poorly encoded, therefore likely to be recalled poorly or inconsistently over time," Hopper added. "They may be a central focus of an investigation but 'failure' to recall such things does not indicate lack of credibility; it just means they weren't encoded in the first place, as expected from brains responding to assault, fear and trauma."

Hopper also spoke of the reflex response that the brain sends to the body when it perceives a "no escape" scenario.

"Reflex responses are hard‐wired into human brains because we evolved as prey, not just predators," Hopper said. "These range from a brief 'freeze response' when attack is detected, to extreme survival reflexes including dissociation, inability to move or speak or even pass out."

For more than 25 years Hopper's research, clinical and consulting work has focused on the psychological and biological effects of child abuse, sexual assault and other traumatic experiences. As a clinician, he works with adults who have experienced abuse as children and assault as adults. In his forensic work, both criminal and civil, Hopper testifies on short- and long-term impacts of child abuse and sexual assault. Hopper was a founding board member and longtime advisor to 1in6 and served on the Peace Corps Sexual Assault Advisory Council. He consults and teaches nationally and internationally to military and civilian investigators, prosecutors, victim advocates, commanders and higher education administrators.

The attendees of this forum included SHARP Academy students, personnel from Fort Leavenworth, Fort Riley and Fort Leonard Wood, as well as college and university representatives from Missouri and Kansas.

"Universities share the same age demographic --18 to 24 years old -- as the military," said Col. Geoffrey Catlett, director of the U.S. Army SHARP Academy. "Partnering with colleges helps us both gain a better understanding of the issue of sexual assault."

This SHARP Professional Forum is part of a quarterly series the SHARP Academy and Fort Leavenworth SHARP Program Office hosts.

"The SHARP Professional Forum is about bringing in subject matter experts from around the country in order to provide a broader perspective on this issue of sexual violence in the military," Catlett said. "Dr. Jim Hopper is a leader in looking at the neurobiology of sexual trauma. Bringing him here to shines a light on how a brain responses to assault is a critical piece in understanding this issue and then -- as SHARP Professionals -- being able to respond with sensitivity and confidentiality effectively to people who have been sexually assaulted."

Related Links:

U.S. Army Combined Arms Center

U.S. Army Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention (SHARP) Academy

Social Sharing