FORT SILL, Okla. (Oct. 27, 2016) -- "We know that Oklahoma experienced 907 magnitude 3+ earthquakes in 2015, 585 magnitude 3+ earthquakes in 2014 and 109 in 2013." --Earthquakes.OK.gov

The 5.8 magnitude earthquake in Pawnee, Okla., in the early morning hours of Sept. 3, was felt in seven states, and the increased incidence of Oklahoma quakes has gotten the attention of emergency managers, scientists, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

To shed light on the reasons and probabilities, Stanford University researcher F. Rall Walsh III addressed around 50 Fort Sill leaders in the Reimer Conference Center at Snow Hall, Oct. 19. Walsh, a PhD candidate in the Department of Geophysics, specializes in understanding man-made earthquakes in mid-continental United States.

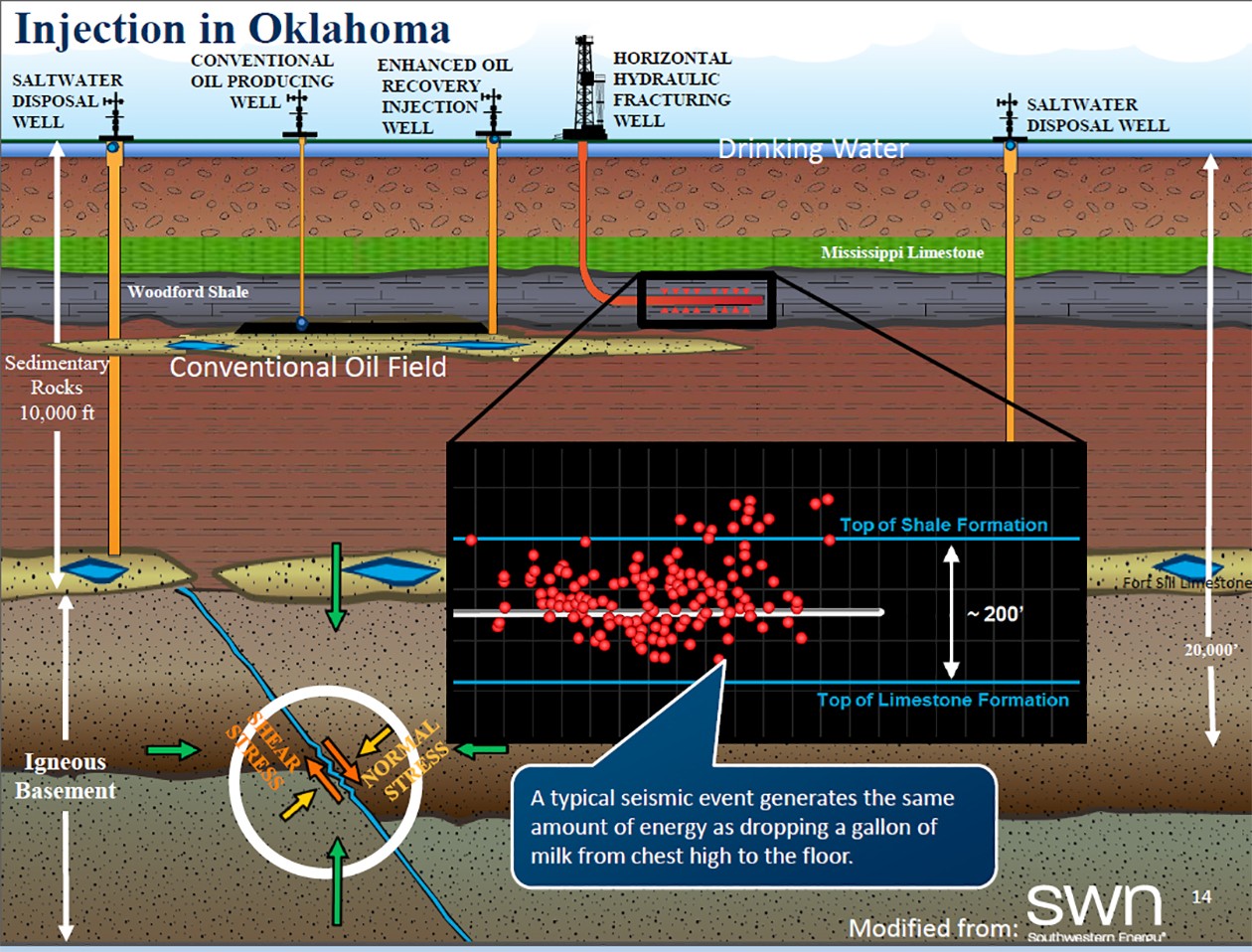

"Around 2009 the rate of earthquakes in Oklahoma significantly changed," he said, showing maps where they occurred, and relationships of earthquakes to oil and gas extraction such as fracking and enhanced oil recovery (EOR) processes during that time.

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, occurs in thin beds of shale 100 to 300 feet thick, and involves the high-pressure injection of water, sand and chemicals to crack the rock and force out the oil or gas imbedded in it. If this is done near a geologic fault, it can set off a quake.

However, it's not the fracking per se that causes most of the quakes, but the disposal of salty wastewater from both fracking and conventional oil fields that creates most of the earthquakes, said Walsh. The resultant wastewater is usually contaminated with salt and sometimes naturally occurring toxic chemicals or radioactivity. So to prevent contamination of surface water, it is injected deep into the earth's sedimentary rock layers, and that is what can loosen the previously stable faults.

According to the website Earthquakes.OK.gov, the EOR extraction method, "injects fluid into rock layers where oil and gas have already been extracted, while wastewater injection often occurs in never-before-touched rocks. Therefore, wastewater injection can raise pressure levels more than enhanced oil recovery, and thus increases the likelihood of induced earthquakes."

Approximately seven to 10 barrels of wastewater can be produced for each barrel of oil produced. "There are over 100,000 saltwater disposal wells in the U.S., most with no relationship to earthquakes," said Walsh. "But sometimes their fluid pressure can unclamp cracks in the earth and allow them to slip."

While the location of several geologic fault lines is known, Walsh said, "Most of the earthquakes occur on faults we don't know about." The Meers Fault, which was the site of a major earthquake 1,300 to 1,700 years ago, runs right through Fort Sill.

In a paper he co-authored, published in the Science Advances journal June 2015, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Walsh suggested that reinjecting wastewater into the depleted rock layers the oil was removed from, instead of in the deeper layers, should decrease the chance of quakes.

Oklahoma now has more magnitude 3-plus earthquakes than California. He added, "You didn't move to earthquake country. Earthquake country came to you."

The U. S. Geological Survey predicted the chance of light earthquake damage in 2016 for the area east of Woodward, Okla. to be 10 to 12 percent, and the probability for the area where the 5.8 magnitude quake occurred (Oklahoma's largest recorded to date) as 5 to 10 percent. The Lawton-Fort Sill area, which is away from the major injection well activity, is in the 1 percent probability zone.

Walsh said there are oil fields to the north that, if developed in similar fashion, could increase the probability of a major quake here. There are also several dams in the area, so flood hazards need to be assessed as well.

Other places where quakes increased historically due to high pressure injection of waste fluids deep into the earth are the Rocky Mountain Arsenal near Denver, and Chevron's Rangely Oil Field in Rangely, Colo.

Early warning systems for earthquakes aren't planned for Oklahoma, although they are used in Mexico and Japan, and are being planned for California, with some starting to use smart phone apps. They allow several seconds of warning depending on the distance from the quake's epicenter, and could save lives by halting weapons training and handling of explosives and chemicals, stopping elevators and opening doors at the nearest floor, and preventing airplanes from landing.

Preparations for the possibility of a quake are the same as for any hazard (see www.ready.gov/earthquakes). If caught in a quake while indoors, you should "drop, cover, and hold on." In other words, hide under something such as a table that will decrease chances of falling debris hitting you, and hold on to it.

"Don't try to run from the building," said Walsh. "Don't stand in a doorway unless you live in an older home. Modern buildings are safer now." Proactive measures include bolting bookshelves, file cabinets, water heaters, refrigerators and the like to a wall to reduce their chances of falling on someone.

FEMA Region 6 representatives also spoke to the gathering about disaster planning, and said that they will develop an earthquake disaster response plan for Oklahoma in the near future.

Resources:

www.Ready.gov/earthquakes

https://earthquakes.ok.gov

earthquake.usgs.gov

Social Sharing