Editor's note: The Pentagram will publish occasional columns by writer Col. Patrick Duggan, JBM-HH's commander. This is the first in a series of stories intended to provide context to the policies, endeavors and rich history of innovation of JBM-HH.

Innovation. It seems like a modern-day buzzword. Yet, a quick search on Google Ngram viewer shows that the word has actually been around for hundreds of years, since 1510, to be exact. And while the word innovation was not as popular in the Industrial Age as it is in today's Information era, its spirit on Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall certainly remains as powerful. You see, innovation has been a timeless companion to JBM-HH's own history of innovation, and is figuratively, and literally, woven into the historical fabric of our nation. This article serves as part one of three short pieces which highlight JBM-HH's own history of innovation, and how, even today, heralds future endeavors. JBM-HH recognizes that one can't build a base of tomorrow using the infrastructure of the past, so it is exploring new community partnerships, innovative solutions and modern systems to propel its march forward. Luckily for JBM-HH, its rich history of innovation serves as a colorful guide to its "future of innovations."

Early History

Starting from humble beginnings, what is now JBM-HH was once part of a 250-acre tract of forest appended to a larger 1,100 acre gentleman estate, owned by George Washington Parke Custis. G.W.P. Custis inherited it from his father John Parke Custis, who was Martha Washington's son from a previous marriage, and adopted son of President George Washington. G.W.P. Custis owned the property from 1801-1861, and lived in what is now the Arlington House, which overlooks Washington, D.C., and the Potomac River on Arlington National Cemetery grounds. G.W.P. Custis's daughter Mary Anna Randolph Custis married then-Lt. Robert E. Lee, who also spent many years on the estate. Of note, one of the earliest tracts of land, located in the southern most portion of Arlington National Cemetery and the Navy Yard Annex, was called Freedman's Village, and was a refuge for freed slaves from 1863-1866. The Freedman's Village Bridge connects Washington Boulevard and Columbia Pike in Arlington and was dedicated last year in honor of that refuge for freed slaves.

Innovative Design

JBM-HH has had an incredibly rich history of innovation since its beginning. As described in author John Michael's book "Images of America--Fort Myer," the base has witnessed numerous U.S. milestones ever since the Civil War.

Subsequent to JBM-HH's role as part of the 22 interlocking defenses encircling Washington, D.C., during the Civil War, then-Fort Cass and Fort Whipple were merged into a dedicated base for U.S. Army officer quarters. Part of its initial innovative design involved constructing officer housing to overlook the Potomac River instead of parade fields, which conflicted with military tradition of the time. Unorthodox thinking also led to building officer houses in a row, for a decidedly more urban feel than what was typical of U.S. Army fort constructions of the day. After the Civil War's denuding of the forests in the area, fort planners deliberately planted shady trees along Grant, Jackson, and Lee Roads for aesthetic feel and Victorian charm, as well as erected street lights and street signs, in contrast to other spartan Army forts. Even the circulation patterns of the roads: Washington Avenue, Grant Avenue, Jackson Avenue, Custer Road, Lee Avenue, and Johnson Avenue dated back to post-Civil War construction and echoed the urban vibe. In short, JBM-HH bucked the military traditions of the day to innovate for the future.

Home of Innovation--Civil War to WWI

JBM-HH has been the home of many innovative organizations. From 1869-1910, JBM-HH served as the home of Signal Corps Officer training, and under the Chief Signal Officer of the Army and its namesake, Maj. Gen. Albert J. Myer, experimented and perfected many new communication technologies for the military. This included the signal system known as "wigwagging" that involved messaging with flags during day and lanterns at night. The Signal Corps established the Army's first telephone system on Fort Myer in 1877, just 18 months after Alexander Graham Bell received his patent, which connected the base via direct circuit to Washington, D.C. In 1878, the Army installed an additional 45 miles of copper lines across the surrounding area, which connected nearby cities to the base. The Signal Corps also standardized the use of heliograph tactics for the military, which involved directing and flashing sunlight to convey messages over great distance, and often used Whipple Field and the foot of the Washington Monument to pass heliograph traffic.

In 1870, the U.S. Weather Bureau was established on JBM-HH. The Weather Bureau relied on extensive trans-national telegraph lines to compile voluminous dispatches, processing up to eight reports a day from 224 weather stations, to feed D.C. decision makers.

JBM-HH was the home for one of the first electric passenger train service cars from 1890-1930, connecting Rosslyn to the base. The passenger terminal was located at the intersection of Lee Avenue and McNair Road, just across from the former base hospital that is currently JBM-HH's headquarters.

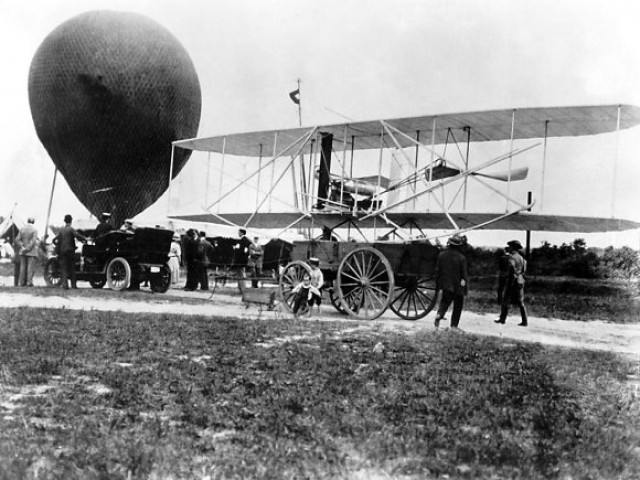

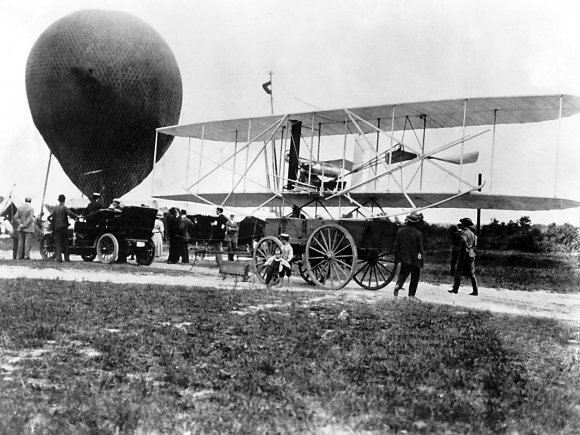

JBM-HH was the home of U.S. Army Observation Balloon training from 1902-1927. Flight training on SR-1 (semi-rigid dirigible) started in 1908, with SR-1 achieving the first earth to balloon radio transmission the same year. One of the dirigible's first three graduates was Lt. Thomas Selfridge who would unfortunately later become the first fatality in military aviation history Sept. 17, 1908. This occurred when one of the propellers on the Wright Flyer shattered, resulting in the aircraft plummeting 75 feet across from what is currently JBM-HH's Tri-Services Parking Lot (across from Spates Community Club), killing Selfridge, and injuring pilot Orville Wright. Wright was hospitalized for six weeks.

JBM-HH was the home for the establishment of U.S. Army Aviation, and during September 1908 and September 1909, Wright launched numerous demonstration test flights for the U.S. Army on Summerall Field. The flights culminated in a 10-mile trip to Alexandria, averaging 43 mph, in September 1909, after which the Army formally accepted Wright's design and started training aviation pilots of its own.

JBM-HH was the home of the nation's first wireless communication towers in 1913. Known as the "three sisters," they were three radio towers that resembled the Eifel Tower, and existed until 1940. The tallest was 600 feet and the other two were 450 feet tall, and in 1915, they achieved the nation's first Trans-Atlantic voice communication to Paris, France. Incidentally, the three sisters connected the transmission with the real Eifel Tower. Also of note, the entire U.S. started to set its official time according to the radio signals of JBM-HH's three sisters.

During World War I, JBM-HH was used as a central location to train Soldiers on trench warfare, and was overseen by experienced French and U.S. expeditionary officers. On the grounds of what is currently the commissary, U.S. doughboys practiced some of the first combined arms warfare tactics of the modern age. In 1917, JBM-HH became one of the first sites to host Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) summer training after Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916, which established ROTC programs across U.S. universities and colleges.

The Pentagram will publish part II of JBM-HH's history of innovation (mechanization and reorganization) in an August edition, and part III (Base of tomorrow) in September.

Related Links:

Mechanization and Reorganization: A History of Innovation (Part 2 of 3)

The Cyber-Base of Tomorrow -- A History of Innovation (Part 3 of 3)

Social Sharing