WASHINGTON -- In March 1776, as her husband, John, served in the Continental Congress, Abigail Adams begged him to "remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors." Of course, the early legislators did forget women, who didn't receive the right to vote until the 19th Amendment passed, Aug. 26, 1920, a day commemorated as Women's Equality Day. (Some states and territories, particularly in the west, gave women voting rights earlier.)

That amendment passed in large part due to the service of women during World War I and every other major war. Although not always in an official capacity or in uniform, women have faithfully served the U.S. Army since 1775. History has largely forgotten them, but here are 19 examples of their service, from the birth of the nation, through the passing of the 19th Amendment.

#1 - Margaret Corbin

Women routinely followed their men to the battlefield. Sometimes wives even took up arms. When Fort Washington on Manhattan Island came under attack in 1776, for example, Margaret Corbin stood at a cannon beside her husband, handling ammunition. When he was killed, she took his place until she was herself critically wounded, permanently losing the use of her left arm. She then joined an invalid regiment at West Point, New York, cooking and laundering for other wounded Soldiers. In 1779, Congress authorized a pension for her of half a Soldier's monthly pay, making her the first American woman to receive a pension as a disabled Soldier. Corbin died in 1800. In 1926, she was reburied with full military honors at West Point.

#2 - Deborah Sampson Gannett

Women also have a long tradition of disguising themselves as men in order to take up arms. One of the most famous is Deborah Sampson Gannett, who enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment as Robert Shirtliffe (spelling varies) in 1778. Her gender was only discovered after she became ill. She even tended her own bullet wound to escape discovery. Sampson eventually received a small pension, and after her death in 1827, Congress granted Sampson's husband a widow's pension.

#3 - Mary Ann Cole

In the War of 1812, Mary Ann Cole worked as a hospital matron overseeing the care of sick Soldiers during the siege of Fort Erie, Ontario, from July to October 1814, when the Americans surrendered. Cole supervised four nurses who cared for some 1,800 American Soldiers killed or wounded during the battle. Cole also kept medical records, and cooked and distributed patients' meals.

#4 - Sarah Borginnis

Sarah Borginnis (also Bowman) married a Soldier who served in the 7th Infantry Regiment, becoming a laundress and cook for his unit. She also nursed the sick and injured, emerging as a larger-than-life figure during the Mexican-American War. Nicknamed "The Great Western" -- she reportedly stood 6 feet tall -- Borginnis proved fearless. In the midst of a seven-day Mexican bombardment at Fort Texas (later renamed Fort Brown), she shunned the safety of bomb shelters and continued serving meals, loading weapons and patching up wounds even after bullets passed through her bonnet and her bread tray. Borginnis remained with the Army even after her husband was killed. In 1866, she was laid to rest in the cemetery at Fort Yuma, Arizona, with full military honors.

#5 - Mary Walker

After years volunteering in hospitals and on the battlefield during the Civil War, Mary Walker was appointed a contract surgeon to the 52nd Ohio Volunteers in 1864. That April, she was captured and imprisoned at the overcrowded and filthy Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia, where she became ill and developed vision problems that eventually ended her medical career. After she was released in a prisoner of war exchange, Aug. 12, 1864, Walker continued serving with the Army. President Andrew Johnson awarded the Medal of Honor to Walker for her "untiring" efforts in 1865. According to her citation, she "devoted herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded … to the detriment of her own health, and has also endured hardships as a prisoner of war." In 1917, two years before Walker's death, the Medal of Honor Board removed her name and 911 others from the list of recipients after rewriting the award qualifications. Sixty years later, the Army Board of Corrections posthumously restored her award. She remains the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor.

#6 - Clara Barton

Another woman who witnessed immense suffering on the Civil War battlefields was Clara Barton. She began her service volunteering in Washington, D.C. hospitals, visiting the troops and organizing donations of clothing, food and other supplies. Then, she moved to the front lines. The "Angel of the Battlefield," Barton cared for wounded and dying Soldiers from Antietam, Maryland, to Andersonville, Georgia. At the end of the war, Clara Barton received thousands of letters from women wanting to know the fate of their husbands and sons. She and her assistants answered more than 63,000 letters and identified more than 22,000 missing men. Barton founded the American Red Cross in 1881. She later traveled to Cuba and aided Soldiers during the Spanish-American War.

#7 - Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor (née Baker) left behind a diary of her Civil War service, which began when she escaped slavery and reached Union Army lines in Georgia in 1862. Initially appointed as a laundress with the 33rd U.S. "Colored" Troops, her duties multiplied thanks to her nursing skills and her ability to read and write, which she used to teach freed slaves to read. She married Sgt. Edward King, and she and her husband were mustered out, Feb. 9, 1866. She remained a teacher and later helped organize a branch of the Women's Relief Corps.

#8 - Annie Etheridge

Annie Etheridge was a "daughter" of several Michigan regiments during the Civil War, and would run onto the field of battle and administer first aid. "At the battle of Fredericksburg," one Maine recruit wrote in his journal, "(Etheridge) was binding the wounds of a man when a shell exploded nearby, tearing him terribly, and removing a large portion of (her) skirt." Etheridge was wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia. She worked for the Treasury Department after the war, and requested a pension of $50 a month for her service to the Union. She received half, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia.

#9 - Intelligence Agents

Many women served as intelligence agents during the Civil War. Elizabeth Van Lew, who used her Richmond, Virginia, mansion to run a spy ring for the Union, was one of the most successful. She also visited prisoners of war, bringing them food and clothing, even helping them escape. In thanks for her service, President Ulysses S. Grant made her postmaster of Richmond, but she remained an outcast among her neighbors. She died impoverished in 1900.

Rose O'Neal Greenhow and Belle Boyd spied for the Confederacy during the Civil War. As a popular capital hostess, Greenhow operated an elaborate spy ring in Washington, D.C. Boyd fatally shot a Union Soldier who assaulted her mother, then became a Confederate messenger. Both women were imprisoned at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington and eventually published memoirs. Boyd was arrested six times, imprisoned three times, and exiled twice. Greenhow drowned off the North Carolina coast in 1864.

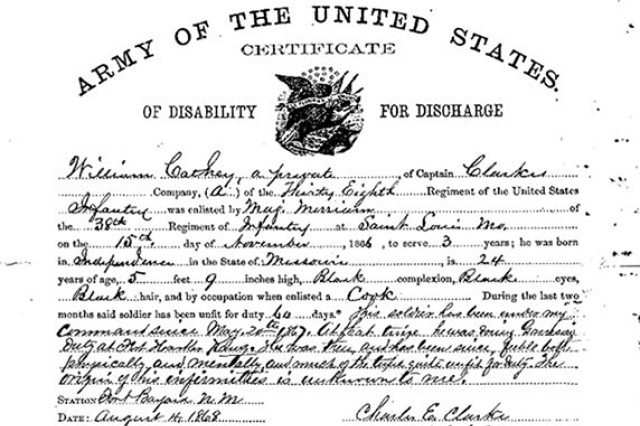

#10 - Cathay Williams

Former slave Cathay Williams served as a cook and laundress for the 8th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. In 1866, Williams enlisted in Company A, 38th United States "Colored" Infantry Regiment as William Cathay, becoming the first documented African-American woman to join the U.S. Army. She served throughout the American West as a Buffalo Soldier until she was hospitalized in 1868, her secret revealed. Despite ill health that dated from her Army days, she was later denied a pension, and died sometime between 1892 and 1900.

#11 - Army Contract Nurses

During the Spanish-American War, the War Department quickly realized it needed nurses to care for Soldiers wounded in battle and brought low by tropical diseases. By the end of the war, about 1,500 contract nurses had served in military hospitals, aboard the hospital ship Relief, in stateside camps, the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico and Hawaii. They often worked in primitive, unsanitary conditions, sometimes as battles raged around them. This included almost 250 Catholic nuns, and also about 80 African-American women. Twenty-one nurses died in the line of duty, mostly from diseases like typhoid and yellow fever. The Army paid the nurses $30 a month plus rations, but the women weren't granted pensions until 1922.

#12 - Anita Newcomb McGee

Anita Newcomb McGee, considered the founder of the Army Nurse Corps, selected and organized the nurses of the Spanish-American War. In August 1898, she was appointed acting assistant surgeon general of the Army for the duration of the war, making her the only woman authorized to wear an officer's uniform. She wrote a manual on nursing for the military in 1899.

#13 - Establishment of Army Nurse Corps

Because of the exemplary performance of contract nurses during the Spanish-American War, U.S. military leaders realized it would be helpful to have a corps of trained nurses on call. The Army Nurse Corps was officially established Feb. 2, 1901. McGee herself drafted much of the legislation, which fell under the Army Reorganization Act.

#14 - National Service School

The National Service School was organized by the Woman's Naval Service in 1916 to train women in preparation for war and national disaster. The Army, Navy, and the Marine Corps cooperated to train thousands of women, representing practically every state, for national service. Women learned food conservation, military calisthenics and drill, land telegraphy, telephone operating, making surgical dressings and bandages, signal work and many other skills.

#15 - Wartime Manufacturing

With the large number of men called to duty during World War I, 20 percent or more of all workers involved in the wartime manufacture of electrical machinery, airplanes and food were women. Women also came to dominate the formerly male professions of clerical workers, telephone operators, typists and stenographers. Such skills, along with nursing, would be needed both on the home front and on the fighting front in the so-called "War to End All Wars."

#16 - Reconstruction Aides

The Navy and Marine Corps were first to actively recruit women to free men for combat during World War I. Thousands applied for 300 or so Marine Corps positions, and another 11,000 women answered the Navy's call to become "Yeomanettes." They occupied noncombat positions, from radio electricians and draftsmen, to secretaries, accountants and telephone operators. Soon, the Army also made use of women's talents as reconstruction aides (physical therapists) in the Medical Corps, stenographers in the Quartermaster Corps, clerks in the Ordnance Corps, and telephone operators in the Signal Corps.

#17 - "Hello Girls"

The Army Signal Corps recruited and trained at least 230 telephone operators -- "Hello Girls" -- for service overseas during America's involvement in World War I. Many of them served near the front lines in France and came under fire as they performed critical communications duties. Confusion over whether these women should be classified as limited duty Soldiers, contract workers or something else, meant the Hello Girls wouldn't receive veteran's status until the 1970s -- when only 18 were still alive.

#18 - Army Nurses during WWI

Some 21,000 Army nurses played a critical role in World War I and the influenza epidemic of 1918, the deadliest pandemic in modern times. About 18 million people died from the flu worldwide, and the virus ran especially rampant on crowded Army posts. More than 200 Army nurses lost their lives because they contracted influenza while caring for patients.

More than 10,000 nurses served overseas in France, Belgium, England, Italy, Serbia, Siberia and the Philippines, as well as in Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Army nurses were assigned to casualty clearing stations and surgical teams in field hospitals as well as to mobile, evacuation, base, camp and convalescent hospitals. They also served on hospital trains and transport ships. Several were wounded. Three received the Distinguished Service Cross.

#19 - Motor Corps

Women also served the troops through a variety of nongovernmental organizations. For example, thousands of Red Cross nurses served in hospitals, many in France, while other women provided recreation and morale support services in hospitals, camps and near the front lines. Motor Corps of America women drove and repaired automobiles, gave first aid, carried stretchers if necessary and did various kinds of emergency work. Similarly, the Salvation Army became one of the most devoted service organizations to work with troops during the Great War after its commander, Evangeline Booth, told Gen. John Pershing that while he may have had an Army in France, it was "not my army!" Among other tasks, its workers, mostly women, ran canteens with refreshments and entertainment for the troops.

-----

Editor's note: Special thanks to the U.S. Army Women's Museum, which provided much of the above information. Other important sources are the Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, the Army Medical Department Office of Medical History and the National Women's History Museum websites. Additional resources are hyperlinked throughout.

Related Links:

Social Sharing