As dialogue intensifies around the best ways to reform the acquisition system, many proposals will offer new processes and realigned responsibilities to improve efficiency and effectiveness. However, no matter what changes may come, the Army acquisition system will continue to be reliant upon and driven by people. The system can only be successful through the performance, commitment and motivation of the acquisition workforce. With so much at stake, how can leaders be certain they are using the motivators that match the preferences of their employees? To improve Army acquisition, we must start by increasing our effectiveness in motivating the Army Acquisition Workforce (AAW).

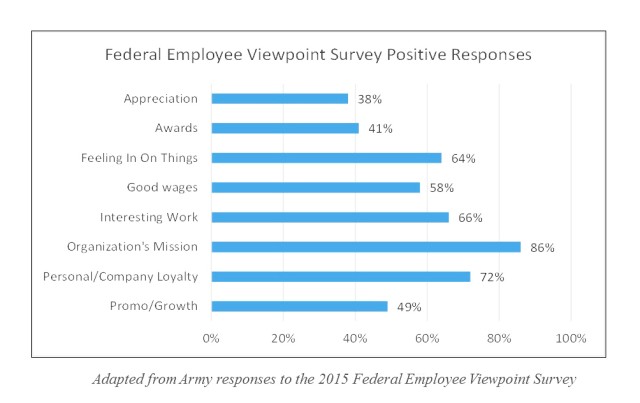

The 2015 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) can be used to evaluate the extent to which AAW employees are motivated today. Results of the Army FEVS responses can be categorized and matched to popular motivators. When doing so, the data show that AAW employees certainly see the importance of their jobs and the connection to their organization's mission. Respondents are generally satisfied with their performance evaluation and performance feedback, enjoy and understand their jobs, and feel that their supervisors encourage individual development and allow a healthy work-life balance. All of these results positively impact employee motivation.

On the other hand, other results of the FEVS show cause for concern. Army respondents do not feel appreciated for their contributions, are not satisfied with pay raises, and do not feel empowered or motivated. Additionally, they feel awards are neither meaningful nor decided in accordance with merit principles. These results are likely to have a negative impact on employee motivation. Based on these factors, it is not surprising that only 42 percent of the workforce reports that senior leaders generate high levels of motivation. Analyzing the survey results against popular motivators throughout research literature sheds light on the driving force for this level of satisfaction.

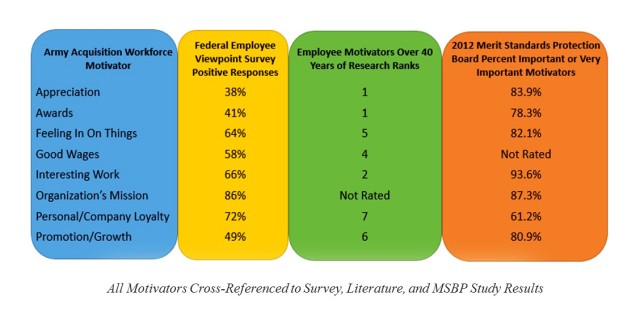

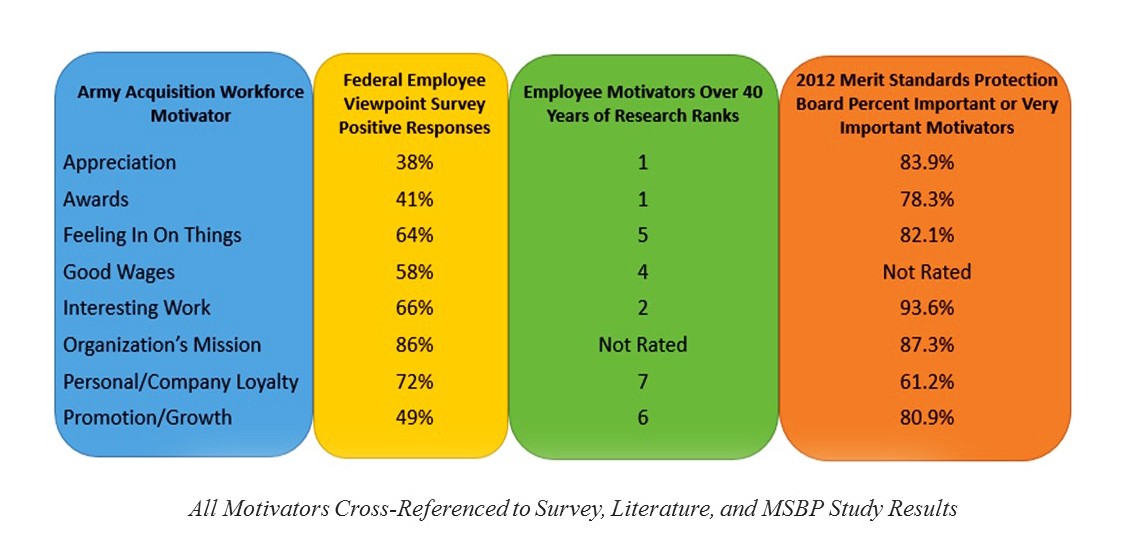

There is a large range in these scores. Three motivators--appreciation, awards and potential for promotion and growth--fell below 50 percent positive responses. Alternately, both the organization's mission and loyalty exceeded 70 percent positive responses. Knowing the importance or priority of these motivators would put these scores in a more useful light. To achieve this, compare the FEVS results to two research sources: Carolyn Wiley's 1997 study on the top employee motivators over 40 years of research and the 2012 U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) Federal Employee Engagement study.

The juxtaposition of AAW motivators, FEVS results, literature review results and the MSPB report provides a number of insights. First, appreciation is both the lowest-scoring motivator on the FEVS and among the most important motivators, according to both Wiley's study and the MSPB study. Awards are in a similar predicament, although the difference between its perceived importance in Wiley's study and in the MSPB report indicates that it may be more important to the general employment population than the federal workforce. Third, interesting work appears to be a high motivator across all three studies, and it is encouraging that the AAW is generally positive in its current view toward that motivator. Finally, the opportunity for promotion and growth is a somewhat mediocre motivator across both the Wiley study and in the MSPB study. So, while there is much room for improvement in this area, higher priority may be given to other, more highly preferred motivators.

So how can Army acquisition leaders raise the percentage of employees who see senior leaders generating high levels of motivation in the workforce? Before changing anything, leaders should keep doing what is working. According to the FEVS, employees are generally satisfied with their feelings of inclusion, wages, connection to the mission and loyalty of the organization to the individual. In addition, employees are satisfied with the challenge of their work and the potential for promotion and growth. This is promising, especially since interesting work is one of the top employee motivators across all the research. Managers and senior leaders should keep reinforcing these perceptions. Ignoring these strengths to chase improvements in other areas would be foolish; leaders should preserve what they do well to ensure that motivation levels do not slip further. Still, supervisors and senior leaders could improve in two areas of motivation.

First, leaders must take action to make the workforce feel more appreciated. Appreciation can be easily administered and is inexpensive. It can be as easy as saying "thank you" for a job well done. Currently, less than half of employees feel adequately recognized for good work. Many supervisors and leaders are likely trying to show their employees appreciation, but in a manner inconsistent with the employees' preferences. Leaders should engage in dialogue with the workforce concerning what forms of appreciation employees prefer. Some may prefer a quiet "thanks," while other may like to be recognized in front of their peers. Everyone is different. Leaders must first build relationships with their employees to learn an individual's preference in order to adequately recognize the employee's contributions and convey appreciation.

This leads to the second area of improvement: awards. Supervisors and senior leaders must improve their awards programs. Currently, the workforce does not feel awards are used to recognize superior work. Awards must be based on merit principles mutually understood by leaders and employees alike. These programs should be reviewed regularly, at least every few years, to ensure that supervisors, leaders and organizations are objectively awarding employees for greater-than-expected performance or to reinforce desired behaviors. This regular review should include both monetary and nonmonetary awards; it also should include the search for and consideration of adding new awards to the organization's award program. Leaders can reward employees with gift cards, find new ways to celebrate employee and team of the quarter recipients (a Stanley Cup-type rotating trophy) or find creative ways to include all employees in the award process. For example, leaders could install another mailbox next to their standard suggestion box that allows employees to submit a peer's name and accomplishment for award consideration. The possibilities for improvement are endless and only require a little creativity. Failure to improve the award programs not only cheapens the awards, it detracts from their motivational value.

Efforts to improve these two areas will improve the overall perceived motivation in the AAW. However, which area should be prioritized, and should leaders focus on monetary or nonmonetary incentives to award employees? The correct answer is likely that all have to be improved sooner rather than later, with a slight priority given to appreciation based on its relative importance in the MSPB study. Further research on this topic may shed additional light on the motivation preferences of the AAW, allowing leaders to focus their efforts on those motivators with the greatest potential for impact. Here, follow-up research directly querying the AAW and its supervisors to gauge the workforce's motivation preferences and the supervisors' perceptions of these preferences would be useful. Primary research of this type would serve three purposes. First, the results would offer a glimpse into the motivation preferences of the AAW. Second, the results would advance the dialogue related to the congruity or dissonance between supervisors' perceptions of their employees' motivation preferences and the employees' actual preferences. Finally, in terms of practical application, the results would provide AAW supervisors and senior leaders an assessment of what motivates the workforce and whether their actions are in line with those preferences. This assessment would allow supervisors and senior leaders to align their motivating behaviors to individual employee preferences to further enhance workforce motivation.

CONCLUSION

Army acquisition leaders are in the people business. Requirements documents, design specifications, contracts, acquisition plans and every other deliverable needs a person to make it happen. Think of it this way: replace the acronyms and file names on that giant acquisition chart we've all seen with names and faces, because all of those outputs rely on people. None of the proposed acquisition reforms are likely to change this reality. Army acquisition will always be reliant on its most important resource--the Army Acquisition Workforce. As DOD and the Army navigate possible reforms, senior leaders can find increased effectiveness and efficiencies in improving the ability of leaders at all levels to motivate the people around them.

For more information, contact the author at nicholaus.saacks.civ@mail.mil.

This article will be printed in the October -- December 2016 issue of Army AL&T magazine.

Related Links:

U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center

Social Sharing