SIlVER SPRING, Md. -- For the past several months, Army Spc. Chris Springer has walked into the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research's Pilot Bioproduction Facility, donned his lab coat and set to work running tests for researchers closing in on a Zika vaccine.

He's one of very few service members to get to work on the Zika vaccine.

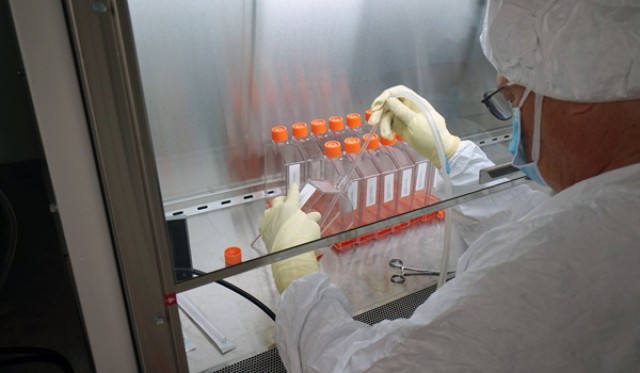

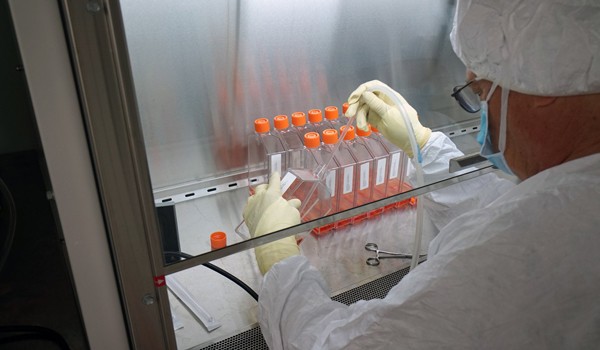

The Maryland facility doesn't exactly have the high-tech feel one would expect. The rooms are reminiscent of a high school chemistry class -- complete with tin foil, glass jugs and plastic tubes. Pinkish-beige rounded bricks line the decades-old walls, which are filled with refrigerators and freezers that give off a collective hum. But it's not about the aesthetics there; it's all about the life-saving products the researchers create.

Unlike many in the science and tech fields, Springer chose the military over a private-sector career, enlisting in October 2013 after receiving a bachelor's degree from Sam Houston State University.

"I thought about joining throughout my life. After college I looked at my options, and it seemed like [the Army] had the best opportunities for me," Springer said. "The military really is the most diverse organization or group of people you'll ever meet."

He had some family in the medical field, so he decided to become a medical laboratory tech. He went to advanced individual training for the specialty and also obtained an associate's degree and a certification. About a year and a half ago, he was assigned to Walter Reed Army Institute of Research as a viral technician.

"I feel very fortunate. I actually wanted to get a field unit, and they put me here, which is pretty much the exact opposite," Springer joked. "But I lucked out."

HOW THEY MADE THE VACCINE

While many vaccines can take years to create, this one took just a few months.

"We actually cleared our calendar so we could do Zika," said the facility's chief researcher, Dr. Kenneth Eckels.

So how did they make it so fast?

Here's the gist:

Pilot Bioproduction Facility researchers received a Puerto Rican strain of the virus, called Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine, from a lab run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February.

Zika is a flavivirus similar to West Nile, dengue and Japanese encephalitis, which the facility has worked on before. With those viruses, researchers applied procedures they developed in their lab to produce a vaccine for human clinical testing. Since those procedures are already in place, and Zika is similar to those viruses, that's also the goal for Zika.

Once initial tests were run by Springer and his colleagues, researchers in biohazard suits moved the virus strain into a clean room to continue testing it. Their job was to make sure the virus strain had been deactivated (just as a flu virus is deactivated in a flu shot).

Last week, the Zika Purified Inactivated Vaccine that the researchers had been working on was successfully completed. It's now being tested for purity, safety and, crucially, its immunogenicity -- whether it provokes an an immune response.

THE PROCESS FROM HERE

If all of the testing is favorable, the vaccine will be given to clinical researchers for phase one of human trials, during which researchers will test the vaccine on human volunteers for safety and immune response. Walter Reed Army Institute of Research officials hope trials will begin by the end of this year.

Researchers have also begun transferring the techniques they developed working on Zika to Sanofi Pasteur, a company with which Walter Reed Army Institute of Research recently signed a cooperative research and development agreement.

Sanofi has the capacity to manufacture the vaccine at a much larger scale for phases two and three of testing, during which researchers will use the vaccine in areas with where the disease is active to study how patients respond.

If it's successful, Sanofi will manufacture the vaccine on a commercial scale. The Department of Defense will then receive the finished product from Sanofi for distribution and use.

Social Sharing