WARSAW - High above the fields and training grounds of Anakonda 2016, a battle for space began.

There were no "Star Wars" or spaceships in this one, only the multiple waves of bandwidth carrying tactical information between groups of Army infantrymen, their counterparts five hours north in Wegorzewo, and those monitoring around the world.

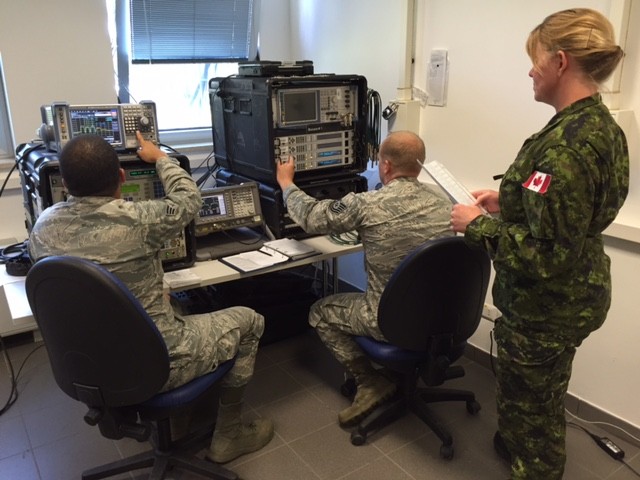

Leading the training were the members of the 527th Space Aggressors Squadron, based out of Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado Springs, Col. Their mission is to block the conversations of those Army Soldiers on the ground and train them to find ways around the disruptions, or, in technical terminology, "the contested, degraded and operationally limited environment."

"It's equivalent to dumping 12 feet of snow and closing down (an information) highway," said U.S. Air Force Maj. Carolyn Winn, mission commander for this exercise assigned to the 527th Space Aggressors Squadron. "(Those facing us) are going to have to find an alternate route, or grab a Snowcat and drive right over us."

There is no guarantee the snow will stop falling.

The other players in this communication game are; some of the 31,000 Soldiers participating in the multinational exercise, to include 4th Infantry Division, 173rd Airborne Brigade stationed in Vicenza, Italy, and those in adjacent events like the 82nd Airborne Division from Fort Bragg, NC.

Specialists, primarily satellite communication systems operators-maintainers, focus on battling the 527th operators from the field. The field operators hooked up to Very Small Aperture Terminals and laptops while troubleshooting the signal interruptions and gaining ground on a potential enemy.

"We model it to fit what we think would be in a real-world scenario," said Winn. "In this region, the threat to satellite communication operations is fairly significant, so we use our more advanced training techniques to get more hands on in a realistic scenario."

That means more than "white card" training, which means handing off a note that tells operators what information systems they can and can't use. Instead, the 527th will be cutting off or delaying their communications using tried and true methods. Everything from the "hot mike" scenario, which is holding onto the transmit button on a radio frequency, blocking everyone from talking, to causing their Internet feed to buffer indefinitely.

"This will be the first live training some of those guys have ever seen," Winn said.

In an operational environment, a short break in communication can be devastating. Without communication from higher echelons, companies fighting on the ground wouldn't be able to coordinate attacks. Pilots flying overhead could lose their bearings, and commanders could lose sight of the battleground through satellite images or those provides by drones.

"It's one of the reasons this training is so important and has been part of the planning for Anakonda 2016 for months," Winn said. "In order to do what we're doing here, we had to get signed off by the Deputy Secretary of Defense."

It took roughly six months to organize and develop the training, which often falls into the classified realm, and is overseen by the 25th Space Range Squadron, also at Schriever Air Force Base. U.S. Air Force Cpt. Eric Lewandowski, liaison officer for the exercise, will be the head referee to ensure everyone stays within the lines of the war games.

"We need to keep them on an even playing field," Lewandowski said. "We ensure everyone is in the boundaries, people know the rules and the offense and defense are able to play."

That means limiting the power of the signal going out, ensuring all participants use a condensed part of bandwidth to not effect civilian users, and remain as safeties to keep the war simulation realistic.

It's a focus U.S. Army Col. Jim Crossley has insisted upon. The U.S. Army-Europe Chief of Space Operations wants this one-of-a-kind group of Air Force elite, who have existed for just about a decade, to test their Army counterparts and to do it realistically.

"The focus of this exercise is to ensure our guys train to fight and win in a contested space domain," Crossley said.

In the 4th Infantry Division tactical operation center, a small village of green tents set up in the Polish countryside, U.S. Army Maj. Brenda Grusing oversees a packed section of noncommissioned officers and Soldiers squeezed next to NATO Allied Forces when the phone call she's on drops.

"Attention in the TOC!" yelled an Army operator.

The room filled with those in Army uniforms of multiple countries, including Poland, Latvia and Hungary, suddenly fell silent.

Communication systems were down. With a storm brewing overhead and moisture-packed clouds possibly to blame, operators ranging from the lowest private to senior NCOs scramble to figured out how to restore communications. Computers, television screens and phones, all connected by wires running digital information through VSATs littered the area.

"There's been several different effects," Grusing said, highlighting the real world effect of inclement weather to the jamming being conducted by the 527th. "As part of the exercise, we've used the 527th to create a contested EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) spectrum."

While phone calls were dropped, secured Army Internet sites that assist in communicating and planning operations stop streaming, modems failed and the information outage expands.

"It tells them something's going on," Grusing said. "We have the aggressor squadron now, providing those effects."

As disruption mitigation begins, the unit increases power to try to override any interrupting signals. They changed frequencies and enacted tactics, techniques and procedures, to include reporting any communications issues. Briefing division assets might have required hand-written verbal communication. It's all part of the process.

"This is a great opportunity for us while training with our allies," Grusing said. "Space is not assured or uncontested as we used to know it. Technology is being established that can counter our access. We are so dependent on our space access, it is critical that we train how to fight through the loss of it."

And when they can't?

"You lose geo-positioning systems, Soldiers can pull out a map and use a map and compass as an alternate," she said, adding that there is always a low-tech backup plan in place to counteract aggressors.

Still, few things replace the efficiency and reliability of their electronic resources.

"It is a tried and true, fast, effective means used for conducting operations, but we need to be prepared," she said.

They were simple white letters broadcast across the rainbow-colored screen:

GOODEVENING HBO

FROM CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT

$12.95/MONTH?

NO WAY!

SHOWTIME/MOVIE CHANNEL BEWARE!

According to a New York Times article "Pirate Interrupts HBO," the protest, read by satellite dish owners on April 27, 1986, was in response to different pay television channels scrambling their programming and charging fees to dish owners. "Captain Midnight," John R. MacDougall, an electrical engineer from Ocala, Fla., decided to transmit a 4 1/2-minute long signal that overrode HBO's broadcast of feature movie, "The Falcon and the Snowman."

The results were, other than a $5,000 fine and probation for MacDougall, the creation of the Automatic Transmission Identifier System. This was a way to track the hacking signal he used, and the attention of the U.S. military, which saw a potential threat from foreign and domestic adversaries.

"It's an event we reference in history that gives support to our mission," Winn said. "It shows that virtually anyone, given the right resources; education, equipment and access, can conduct something of that nature."

MacDougall worked for Central Florida Teleport, which delivered programming for the now-defunct People's Choice network. He finished his work shift that night by pointing a dish at HBO's satellite, Galaxy 1, disrupting their programming by overpowering their signal.

"It's like screaming louder than the guy next to you," explained U.S. Army Maj. Christopher Dziados, lead space integration officer. "You might be able to hear him until the signal keeps getting louder and louder."

The Department of Defense as well as Federal Communications Commission have found ways of better securing their satellite feeds, but the Army knows that the enemy is always advancing its ways of disrupting the battlefield, Dziados said.

"Our (satellite communication) is too important to treat it like it's provided by the cable company," Crossley said. "We're susceptible anytime that a unit deploys to the field and sets up a TOC. When you can't plug in a fiber optic cable."

That's different from the situation in places like Iraq and Afghanistan, forward operating bases could plug in to the rest of the world.

"When there's no fiber backbone, they're dependent on that satellite link," he said.

Social Sharing