Ty Allen was born deaf. While being deaf is an integral part of who he is and how he interacts with the hearing world, he doesn't let it define him.

Like anyone else, the path that led him to Fort Bragg, where he works as phlebotomist, was a winding one. When his path diverged in the woods, he chose to take the one less traveled by others facing similar challenges. And that has made all the difference.

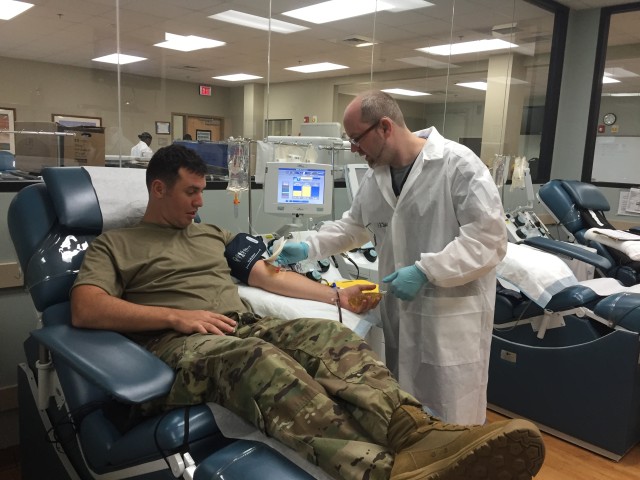

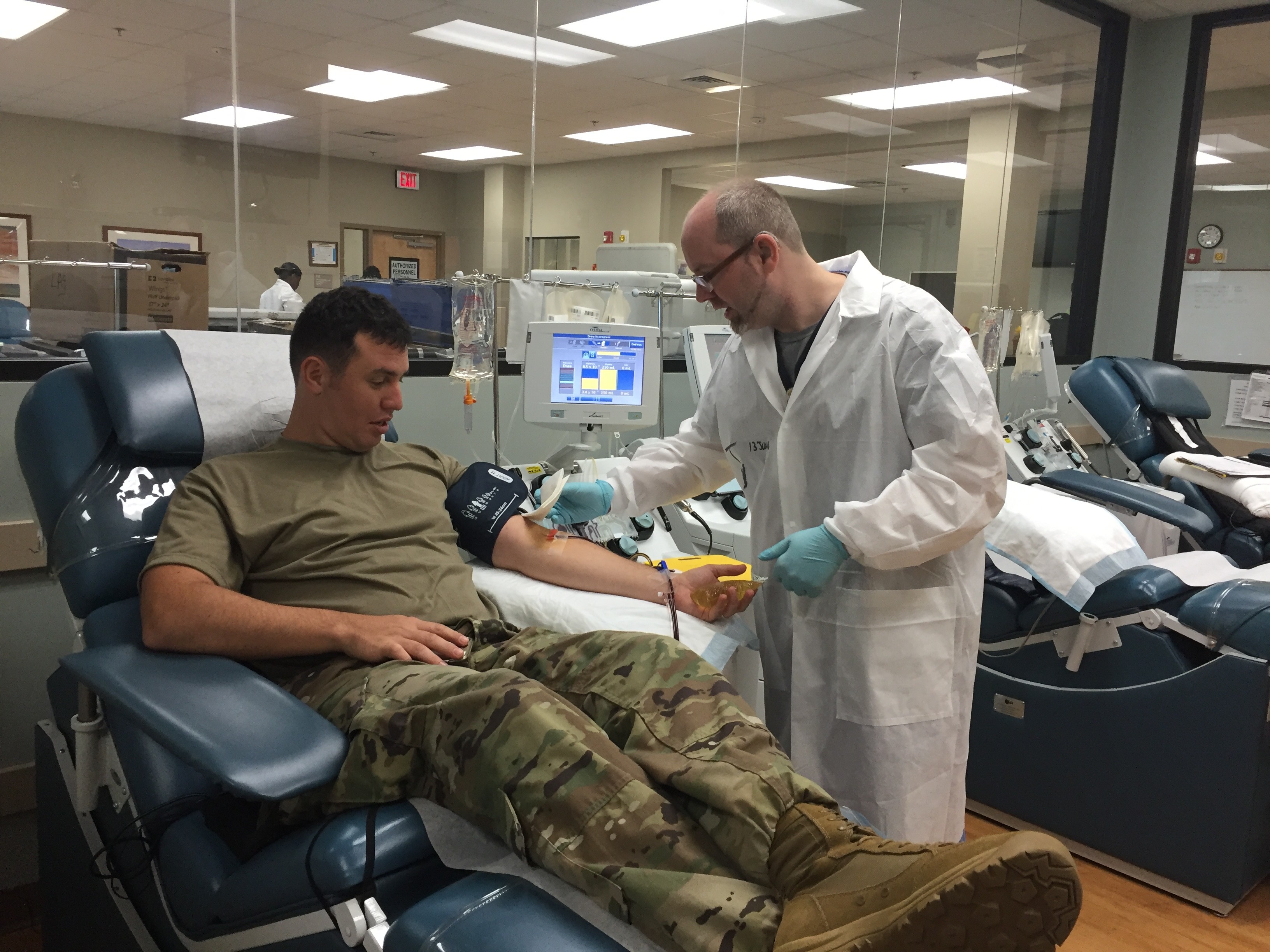

When you first see Allen working at the Fort Bragg Blood Donor Center, his disability is not what you see. You first notice his hands, which work with speed and efficiency as he draws blood, plasma or platelets from the person sitting in the chair.

The grace and precision with which he moves his hands is not all that surprising when you stop to consider that sign language was his first language. His hands have been speaking for him long before his voice.

"I am completely deaf," said Allen when asked about his ability to hear. "That doesn't stop me doing what I'm doing. We all have obstacles that we have to deal with. My obstacle is that I can't hear."

Allen was about 1 year old in his small town of Coffeyville, Kansas, when his parents started to suspect there was something different about their son. He wasn't responding to the sounds of the world around him. When his parents first took him for a hearing evaluation, he saw the movement of the person ringing a bell and looked at them. His parents were told he was fine. They knew better. After further evaluation, they discovered Allen couldn't hear and that his auditory nerve never fully developed.

His parents sent him to school when he was 2 so that he could learn to communicate with the world around him. His now nimble fingers learned to sign. When he was 4 or 5 years old, he learned to speak. He was in speech therapy for 12 years. His voice still has the thickness of someone who is hearing impaired, but he speaks clearly. Without seeing his hearing aids, most people would probably not even realize that he's deaf.

He went to college, earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in computer graphics. However, he faced the same problem of many college graduates; he had the degree, but not the three to five years of experience that most employers are looking for. So, he worked in a clothing store, a candle store and other minimum-wage jobs in order to keep a roof over his head and put food in his belly.

"One of the things about being deaf is that it makes your other senses stronger," said Allen. "I'm a good salesperson. I notice people's body language and their reaction to things, so I was able to help them find what they were looking for. Being in sales helped build my self-esteem and confidence in my ability to be successful in the hearing world."

Becoming a phlebotomist never crossed his mind until his niece, Suzanna, was diagnosed with Wilms' tumor, a rare kidney cancer that primarily affects children. As he visited his niece during her treatment, he realized that he wanted to go pursue a career in the medical field.

"I saw all the nurses taking care of her and decided that's what I wanted to do," said Allen. "I never heard of a deaf nurse, but I wasn't going to let that stop me."

When he went to enroll in a nursing program five years ago, he was told that the classes for that semester were full. When he asked what was available, he learned he could train as a certified nurse assistant or as a phlebotomist.

"My first thought about becoming a phlebotomist was 'heck no,' but I decided to try it anyway," remembered Allen. "I showed up in the class and not only was I the only deaf guy, I was the only male in a class of 25 students."

He said he was shocked that he had to learn how to "stick" a fellow classmate on only the second day of class, but that he was able to master the art very quickly. Something he credits to sign language making him good with his hands. He graduated at the top of his class and found a job at a nursing home. After that he went to work at a hospital and learned apheresis blood collection, which led him accepting a job at the Fort Bragg Blood Donor Center collecting apheresis platelet and plasma donations.

Allen said that the people he's met while working on Fort Bragg are more accepting of his disability.

"The people here on post don't seem to judge me," he said. "If anything, they show a little extra concern and are more aware of talking to me only when I'm looking at them."

Technology has helped Allen, with new hearing aids giving him the ability to hear some of what is going on around him. He's also extremely adept at reading lips and unafraid to ask someone to repeat themselves if he misses something they've said.

"My parents always taught me not to let others treat you differently and don't put yourself down," said Allen. "I sometimes don't even see myself as deaf. I am a part of the hearing world. I have a job. I have a house. I am proud of myself and proud of the two worlds I live in."

Allen said that if he could just change one person's life by sharing his story that it would be good enough for him.

"Don't let anything stop you," he said. "You can't show yourself as a person to pity. You can do whatever you want. You have to earn what you want and work to get where you want to be."

As for the person who changed his life, his niece Suzanna is 8 years old now and doing well. She's even learning sign language so she can communicate better with her uncle.

Social Sharing