EDITORS NOTE:

After Ron Fischer, a retired lawyer for U.S. Steel, received an invitation to his high school reunion in La Crosse, Wisconsin last year, he began making plans to attend. And as he did so, he said he thought of a friend and former high school classmate, Russell Haas, who was killed in action in Vietnam.

He located some of the Soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry who served with his friend and were with him when he died. When these Soldiers learned that he was researching for an article about Russell Haas they invited him to attend the 1-50th reunion at Fort Benning in April of last year.

The research from the trip helped complete the story Fischer wrote about his friend, which was published in the La Crosse Tribune's Memorial Day edition last year (http://bit.ly/1SSiwa0). It also included the story of Bruce Simms, the 19-year-old medic who gave his life trying to save Haas.

During that trip to Fort Benning many of the Soldiers he spent the weekend with told him an interesting story of another man.

The retired steel lawyer from Pittsburgh traveled to Leitchfield, Kentucky where this doctor, the medics' spoke of, was from. It was there that he met and interviewed the daughters and many of the former colleagues and friends of Dr. Ray Cave.

The following is the story of Cave, as written and submitted to the Gold Standard by Ron Fischer in tribute to a doctor he never knew, but whose efforts did not go unnoticed.

Son Of Kentucky- Dr. Ray Cave, M.D.

January, 1968

As Kentucky-born Ray Cave looked up from his just vacated table at the battalion aid station, Landing Zone Uplift base camp, Vietnam, medics approached with a litter borne Soldier who was obviously in the end stage of hemorrhagic shock.

The wounded Soldier's lower legs had been blown away and he appeared listless. The medics lifted the casualty onto the table and Army Capt. Cave went to work. He knew his job was to stop the bleeding and help the breathing. He inserted an intravenous Ringers solution feed into the patient's arm, then placed an endotracheal tube into the soldier's windpipe to maintain an open airway. Spec. 6 Francisco Flores, his right hand man, was at his side monitoring blood pressure and other vital signs.

Cave looked for the femoral artery and the saphenous veins. He applied a clamp to the spurting femoral artery and sutured it. Once the patient's condition had stabilized, he was helicoptered to a surgical hospital from the hardened dirt helipad which was within feet of the aid station.

True to his Hippocratic Oath, Cave had done his job. He had stabilized and medevac'd the wounded Soldier. No one need mention to him that the patient whose life he had just saved was an enemy soldier who had been recovered from the battlefield by Soldiers of Cave's 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry Regiment (mechanized).

July, 1967

Combat medic Pvt. Toby Milroy, from Seymour, Indiana, remembers meeting Cave at Fort Hood, Texas, along with other members of 1-50's medical platoon. Cave was to serve as 1-50's battalion surgeon. By the time of Cave's introduction to members of the medical platoon, Milroy had been indoctrinated about the chain of command. Officers issued orders, non-coms and enlisted men obeyed those orders. Yet Cave did not comport with Milroy's previous impression of officers. From the start, the doctor engaged his charges in conversations about their home towns and interests. He did not rely on his rank to establish the parameters of their relationship. Cave's informality and easy cordiality stood out.

Milroy was more nervous at the prospect of his deployment to Vietnam than he would have admitted. Here he was at 19 years old, responsible to save wounded G.I.s in combat, under fire, with only 10 weeks of medic training at Fort Sam Houston to prepare him.

Sure, he had been taught how to do intravenous feeds, apply hemostats to stem blood flow, inject morphine and apply tourniquets, but those tasks required steady hands and concentration. He and his fellow trainees had been shown recent Vietnam combat footage of horrifically wounded Soldiers--could he perform them while under fire?

Yet, when he met Cave, his mind was put at ease. Discussing in general terms what lay ahead, Cave had a quiet confidence which was reassuring. They would get through this together.

In physical appearance, Cave was not remarkable. He wore glasses and was slightly over 6 feet in height. His blond hair was cut short in a "flattop," a popular hairstyle at the time. He was older than many of the other Soldiers. In manner and appearance, he was impressively intelligent and able, yet he did not seem to call attention to himself. Following that initial meeting Milroy knew the medical platoon was in good hands. But Cave may have had his own doubts.

Shortly after Cave arrived at Fort Hood, he met the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Al Hutson, a decorated WWII and Korean War veteran combat officer. Having been advised of his designation as battalion surgeon, Cave explained to Hutson that he was not a surgeon but had practiced in Leitchfield, Kentucky as a family medicine physician.

According to fellow Vietnam veteran and Leitchfield friend, Miles Thomas, in whom Cave sometimes confided war memories, Hutson would hear none of Cave's disclaimers: "I know where you went to medical school. You're my battalion surgeon!" As his command and the Soldiers with whom he served would later learn, the University of Louisville School of Medicine had well prepared Cave for the challenges of combat medicine in a war zone 10,000 miles from home.

Ray Cave's Roots

That Cave easily related to members of his platoon would not have surprised any of his neighbors and friends in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. He was the boy who grew up enjoying fishing, baseball and music--particularly the trombone. Ray excelled academically in high school and was popular among his classmates.

In Cave's senior year of high school, as a favor to his grandmother, he chauffeured a family friend's daughter and her date to a community dance. Cave was attracted to the pretty lady, who was two years younger. Family lore does not record the name of the young lady's date that evening only that Ray and Frances remained together as a loving couple till a fateful afternoon some 42 years later.

They married two weeks after Frances' high school graduation. Ray sold his trombone to buy Frances' wedding ring and they moved to Bowling Green where Ray earned a degree in biology from Western Kentucky State College--now Western Kentucky University.

Cave entered the University of Louisville medical school (class of '60) along with 88 classmates. One of his classmates, Louisville obstetrician Charles Oberst, remembers their medical training as intensive. Oberst said medical students worked long hours, particularly during their hospital rotations, and their junior and senior years 30 percent of their training was surgery-related. The University of Louisville Hospital was nationally known for its trauma center which had been established in 1911.

Cave and his classmates learned in the operating room at the elbow of renowned surgeons such as Dr. R. Glenn Spurling, who had earlier served as the first chief of surgery at Walter Reed Hospital. And at the personal request of Beatrice Patton-- reinforced by direct order of Gen. Dwight Eisenhower--Spurling had traveled to Germany in December, 1945 to attend to Patton's dying husband, Gen. George S. Patton. The school incorporated into its medical training lessons which had been learned on battlefields in World War II and Korea. The medical school faculty was nationally prominent and strongly committed to public service. Cave's self-confidence and future approach to medicine was well grounded in the training he had received.

Following graduation, Ray moved with Frances and daughter Alicia to Leitchfield, a town of 3,000, about 80 miles south of Louisville. There he joined five other physicians at the Grayson County War Memorial Hospital. The doctor served in multiple capacities as an obstetrician, emergency room physician and general family medicine practitioner. On any given day, he may have delivered babies, treated auto, hunting or farm accident victims in the emergency department or tended as many as 80 patients suffering from illness or malady.

Brenda Riggs of Clarkson, Kentucky remembers her mother bypassing more established physicians to travel from their home in Upton to young Dr. Cave's office in Leitchfield. Her mom suffered from a collapsed lung which had been misdiagnosed by her previous physician. Riggs remembers the throng of people in Cave's waiting room. She also remembers his kindness, corrective diagnosis and timely treatment.

In those days before Medicare and Medicaid, many patients could not afford Cave's services. They would learn not to worry. He treated them without charge and did so quietly without drawing attention. He and his family fit in well with the community, were widely respected and appreciated. Eventually the family had expanded to include daughters Beth and Cara. Life was good.

Then, in July 1966, Cave was inducted into the U.S. Army.

He was commissioned a captain and was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry. In 1967 the 1-50th had an authorized strength of 900 Soldiers, split among four field companies, tactical and special staffs. Cave's medical platoon, 26 in number, consisted of a headquarters' contingent and individual combat medics assigned to each of the platoons within the four field companies.

The battalion was equipped with, and was expert in the use of, armored personnel carriers. The APCs were tracked for overland mobility in rigorous terrain and were each equipped with a 50 caliber and two M60 machine guns. While at Fort Hood, the 1-50 was administratively transferred in August 1967 from the 2nd Armored Division to the fabled 1st Air Cavalry division, already deployed and blooded in Vietnam. Troopers within the 1-50 wore the vaunted 1st Air Cavalry shoulder patch, and the air mobile 1st Cav would now have the overland mobility and punch earlier missing from its arsenal.

USNS General John Pope

On Sept.1, 1967 Capt. Ray Cave along with the rest of the battalion boarded the troopship, "USNS General John Pope," in Oakland, California and began a three-week voyage to the Republic of South Vietnam. The "Pope" was designed for maximum capacity, not for comfort. Officers were paired in rooms about the size of walk-in closets. Cave's roommate was Company B., commander, West Point alumnus Capt. Dick Guthrie (U.S.M.A. '63). He would later retire as an Army colonel.

Upon learning of Ray's passing many years later, Guthrie wrote of the doctor as a "blend of considerate and pensive…" Company A., commander, Capt. John Topper, who hailed from Santa Claus, Indiana and retired as an Army colonel, remembers lengthy conversations with Cave in the day room about medicine. Topper had started out as a medic and so shared Cave's interest in medicine. He was impressed with Cave's breadth of knowledge, but was even more impressed with how down to earth he was.

The ship arrived in Vietnam at Qui Nhon Sept. 22, 1967. Russ Haas, Company C., wrote in a letter to his family in La Crosse, Wisconsin that the temperature was already over 100 degrees when the "Pope" docked at 9 a.m.

LZ Uplift

During most of Cave's service in Vietnam, he and the battalion were based at Landing Zone Uplift, a base camp situated in the Central Highlands in the midst of hostile hamlets and enemy troop concentrations. The North Vietnamese main supply route, the Ho Chi Minh trail, fed directly into this area. The primitive basecamp was a square half-mile piece of dirt, mud and more mud. Continually under threat from enemy attack, Uplift's perimeter was marked with three rolls of concertina wire stacked in pyramid style. Fire posts were set up with machine guns inside the perimeter to repel attackers; outside the wire there were additional foxholes to serve as listening posts and to give warning for troopers.

Cave's medical practice in Vietnam was dictated by unusual challenges. He was responsible to minister to Soldiers who lived on life's edge. The troopers within the four line companies spent up to a month in the field during serial search and destroy missions which were punctuated by all too brief respites of two or three days back at Uplift. They were vulnerable to land mines, leeches, immersion foot, mosquito-borne malaria, oppressive heat, monsoon rains and ever-present fatigue. The Soldiers made enemy contact on almost a daily basis and the resultant psychological stress was continuous. On Dec. 13, 1967, Spec. 4 Haas wrote home "…I don't like having my life hanging on a string 24 hours a day." On Jan. 26, 1968 he wrote he was going into the field that day, "That's why my handwriting's shaky." Later, Haas would earn two purple hearts and a bronze star for valor, awarded after he was killed in action March 2, 1968.

Haas' platoon was pinned down by the North Vietnamese outside Thuan Dao as enemy fire became even more intense, especially coming from a hedgerow some 25 yards away. The platoon's ammunition was running low, and nothing seemed to penetrate the hedgerow. Eventually, Haas sprang into action as troopers attempted to give him covering fire while he raced toward the hedgerow, grenades in hand.

Haas covered most of the 25 yards to the hedgerow before he was cut down by enemy fire. Within seconds the unarmed medic, Bruce Sims, was running to Haas. Every other man in the platoon concentrated his fire on the hedgerow. Sims reached Haas and began to drag him back toward cover when he, too, was shot down. For his actions, Sims posthumously received the Silver Star.

During Cave's tour Topper, who became the battalion's S-2 intelligence officer, recalls the battalion was engaged in 14 major battles. The battalion's Vietnam War Memorial at Fort Benning, Georgia, honors 239 troopers who paid the ultimate sacrifice--including Haas and Sims.

The battalion's heavy casualty rate was not surprising. The 1-50 was a stepchild. It served under the 1st Air Cavalry till March 1968, then the 4th Infantry Division for a month before transferring to the 173rd Airborne Brigade. For each of its parent units, the 1-50 was the fire brigade, the unit which because of its mobility and fire power was called upon time and again to meet the latest enemy threat. The battalion's lack of long-standing connection to its parent units also had implications for supply. It found that it sometimes could not rely on divisional chains of supply. The 1-50 became well practiced at cadging, wheedling, scrounging and trading for supplies. The medical platoon took second seat to no other unit when it came to obtaining stock via unofficial means.

Each month Cave's medics tread the 45 miles of highway between Uplift and the 85th Evacuation Hospital at Qui Nhon to barter for supplies. Not only did the battalion aid station receive necessary supplies, but troopers in from the field knew they could count on Cave and his medics for a steak and beer whenever they visited the dirt-floored "patio" aside the battalion aid station. And when Cave's duties allowed, he would join them.

Capt. Charles McAleer, who would later retire as a lieutenant colonel, served as the battalion's chief medical operations officer and worked closely with Cave. He remembers Cave had a way of assuring wounded Soldiers, often by tone of voice and by placing a hand on the patient's shoulder, as if to reassure the patient that he was in good hands and all that was necessary would be done.

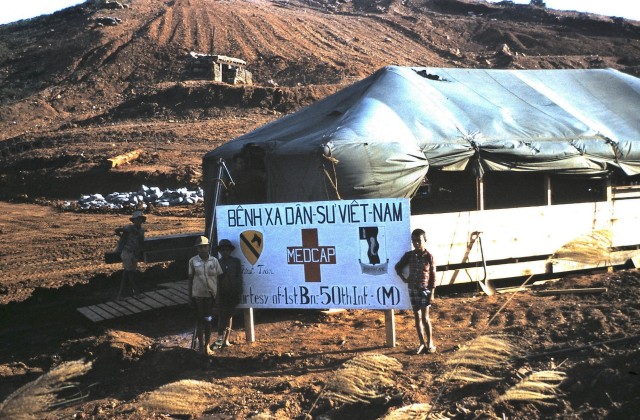

The medics who staffed the battalion aid station grew in experience and expertise under Cave's tutelage. A few of the battalion aid station staff, such as nurse Francisco Flores, were experienced before setting foot at Uplift. Many, however, had only their training at Fort Sam Houston to prepare them for the victims of battle and of tropical illness who flooded their aid station. Through their "on the job" training provided by Cave, they progressed; so much so that when Cave had an aid station constructed outside Uplift's wire for the indigenous civilians, it was often staffed with medics alone.

McAleer could always be sure of one thing: that sometime during each day he would see Cave writing home to his family. It might be very late at night. It might even be after the artillery batteries on Uplift's "Duster Hill" had begun to systematically pummel surrounding enemy positions with cannonade--the nightly out-going barrages were called "red splashes--but at some point each day the doctor would share his thoughts with his wife and family while hunched over a desk with pen and paper.

February 3, 1968

Toby Milroy remembers the firefight at Vinh Nhon too well. He remembers watching Lt. Bob Ballard, the cheerful executive officer with the Louisiana drawl, charge forward before suddenly going down. Milroy rushed forward to render aid. Just as he reached the prone Ballard, he heard automatic weapons fire from behind and saw an enemy soldier go into fatal spasm not more than 5 feet in front of him. Someone, Milroy never found out who, had just saved his life.

The enemy's lifeless form collapsed into the spider hole which had earlier shielded him from view. Ballard was motionless. He had been struck with an RPG from such close range that the missile had not detonated when it struck him. Soon Guthrie, Cave's roommate aboard the "Pope," was there. Milroy and Guthrie carried Ballard to the command helicopter. In air, Guthrie radioed the battalion aid station and alerted Cave that their friend was badly wounded and in need of a miracle. Minutes later the helicopter landed at Uplift's helipad, close to Cave and the awaiting medics.

The doctor immediately went to work aside the helicopter on his friend's inert form, desperately trying to resuscitate some sign of life. Nothing that Cave had been taught by the venerable Dr. Spurling or at his distinguished alma mater would be of use to him today. He had Ballard carried to the aid station, as if the change of venue would serve a purpose. But it did not. Those who had grown accustomed to Cave's soft-spoken nature were surprised at the oaths he uttered as the doctor gradually realized his friend was gone.

Dr. Cave returns home

As Cave neared the end of his tour in Vietnam, he did not relent in his daily regimen in tending to his Soldiers, yet he grew excited at the prospect of returning to his family. On June 25, 1968 he wrote his last letter home. Clearly, he loved his family and despite all, he had retained his humanity and sense of humor. He wrote his wife, in part:

"Dear Madam,

Received your inquiry this date as to my future plans. You are correct in that I am soon to retire from military service. I might be interested in a full time job as you offer, as both husband and father. I might even be interested in a sideline as physician in a small country town. There are a few stipulations though which if you will accept I will definitely say yes to your offer.

First, I must have a loving wife of about 32 years of age. I would expect her to be able to cook, sew, iron, wash clothes, and be a good housekeeper. I would also prefer that she be interested in sporting activities such as bowling and fishing.

The children must be all females, cute, loving, vivacious, and in the approximate age ranges of 3 to 8 years. I would prefer approximately three daughters.

The country town should preferably have a population of around 3100.

If your offer will meet most of these criteria, let me know and I will make definite plans immediately to accept your offer…"

Cave was separated from military service at Fort Lewis, Washington July 17, 1968 and returned to his family and home on Miller Avenue. Leitchfield had not changed during his time in service, nor had Cave, at least not in any way that was discernible to his family and friends. He rarely talked about Vietnam, about the bronze star for meritorious service which had been awarded him, the combat medical badge he had earned for having served in combat under direct enemy fire, about the friends he had lost or about his days at LZ Uplift.

His skills as a physician had been honed by his experience in Vietnam. His hospital rounds began at 4 a.m., and by the time he made it to the clinic at 8 a.m., the waiting room was often full. Patients didn't need appointments, but could simply walk in. He retained the assuring demeanor Toby Milroy and Chuck McAleer had observed years earlier at Fort Hood and LZ Uplift. Cave continued to instill in his patients the sense that all was being done that was necessary, that to the extent humanly possible, he had everything under control. He still had the steady assuring voice, and the ability to communicate with a sympathetic hand on the patient's shoulder.

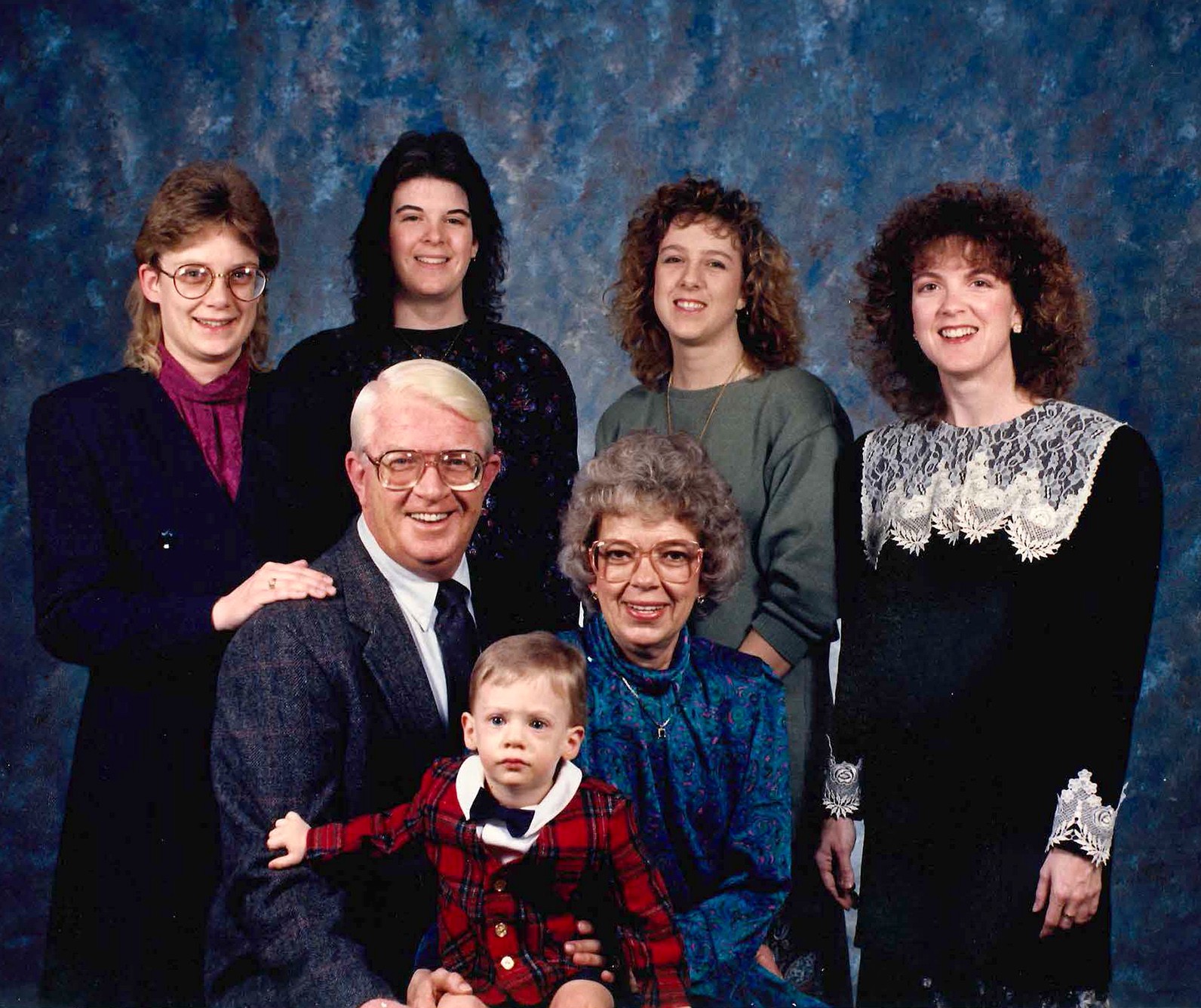

Cave's family flourished as a fourth daughter, Diana, was born in 1970. His practice grew and the group of physicians who had staffed Grayson War Memorial Hospital on East Market Street expanded to include talented young doctors recruited from far away. The old hospital building was no longer adequate, so a large regional medical center built in the late '70s on the west side of town, the Twin Lakes Regional Medical Center. Hospital staff now included some 35 highly trained physicians. Throughout the changes, Cave remained a steadying and guiding influence.

Had any of his medics seen Cave in his later years, they would have recognized the same down-to-earth, skilled physician they had known at Fort Hood and LZ Uplift. During breaks at the hospital, he could most likely be found, not in the doctors' lounge, but talking outside with ambulance drivers, technicians and nurses.

He would retreat for private moments doing what wasn't possible in Vietnam, fishing in his 16 foot aluminum boat on Kentucky lakes and in this simple way the doctor relaxed. No one knows to what extent his war memories intruded on those private moments, whether he dwelled often on his friend Bob Ballard, troopers like Russ Haas or others who are memorialized at Fort Benning.

Sept. 15, 1994

Dr. Joe Petrocelli hadn't counted on this. The straight-speaking trauma surgeon from New Jersey had moved to Leitchfield many years earlier and had grown to rely on Ray Cave as a friend and mentor. But this day he had received an emergency call from the ambulance crew alerting him that they were enroute with Cave to the hospital. The ambulance arrived with police escort and sirens.

Cave had earlier been driving home to have lunch with Frances, as he did every day, when he was stricken. He tried to get back to the hospital but didn't make it. Minutes later ambulance attendants discovered Cave's car which had careened off the road.

Ray Cave was wheeled into the operating room and upon examination, Petrocelli was stunned. Cave's aorta had ruptured and his abdominal cavity was awash in blood. Petrocelli did his best, but he knew it was not enough. The second most difficult thing Petrocelli did that day was to go in the adjoining room and explain to Frances and her daughters that despite his best efforts their loving husband and father had passed on.

Final Notes:

The Kentucky Medical Association later posthumously honored Cave with a resolution, recognizing him as "a remarkable gentleman and country doctor" and specially noting his exemplary service to the poor. He had, according to the KMA, brought great credit to his profession through his commitment to patient care and through his personal sacrifice.

And while many remember the dedicated country doctor who served his country so compassionately, Guthrie probably summed it up best in his post in memory of his old friend to the 1-50th association's website:

"Ray Cave was a great doctor and an even greater human being, who truly cared for our Soldiers. Each and every one. Directly or indirectly, every man in our battalion was better off as a result of Dr. Cave's tireless efforts on our behalf. We owe him our gratitude, our respect. May his soul rest in peace."

Social Sharing