Since 9/11, U.S. forces have been involved in continual operations in areas where camels dwell. While this has provided photo opportunities that can seem quite exotic, few realize that the Army once experimented with camels as an asset on its own soil.

Camels have been used by other militaries for centuries to haul baggage and conduct cavalry operations. As the United States began expanding westward, particularly after the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, the nation acquired territory that had a different terrain than the east coast. It included many desert and arid regions where U.S. Soldiers established forts after the war with Mexico and the 1845 annexation of Texas.

ACQUIRING FUNDING

As early as 1836, advocates were pushing the idea of the Army using camels, but Congress did not approve funding for military experimentation with camels until 1855.

The real push for camel experimentation appeared in 1848 when Maj. Henry C. Wayne of the Quartermaster Corps advocated camel use. Wayne sought the support of Jefferson Davis, a senator from Mississippi and the chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Davis was unable to successfully acquire funding from Congress on the project.

In 1855, as the secretary of war, Davis tried again and succeeded in obtaining the funding needed to acquire the camels. Congress appropriated $30,000 for camel acquisition. The secretary of war tasked Wayne to purchase these camels in the Mediterranean region.

ACQUIRING CAMELS

The USS Supply was then tasked to carry the camels to the United States. Lt. David Dixon Porter, commander of the ship, ensured it was fitted for camel transport and care. Porter and his crew departed New York City in the spring of 1855 en route to Italy to conduct another supply mission after which they would pick up Wayne for the journey. While waiting for Wayne, Porter visited Pisa, Italy, where he observed camels owned by the Duke of Tuscany.

Wayne proceeded to Europe separately. He stopped in the United Kingdom to visit camels in the London Zoological Gardens. Wayne then traveled to Paris to discuss camel use with the French military. The French had been using camels in Algeria already and had military experience with the animals.

Wayne linked up with Porter in Italy, and they began their voyage to Tunisia, stopping in the modern countries of Turkey, Greece, Malta, and Egypt along the way. The officers also traveled to Crimea to interview British officers about their experience with camels in the Crimean War and in India.

By mission end, 33 camels, both male and female and several types of breeds, were acquired in Turkey, Egypt, and Tunisia for the experiments. Saddles and covers were also purchased, and five Arab and Turkish camel drivers were hired.

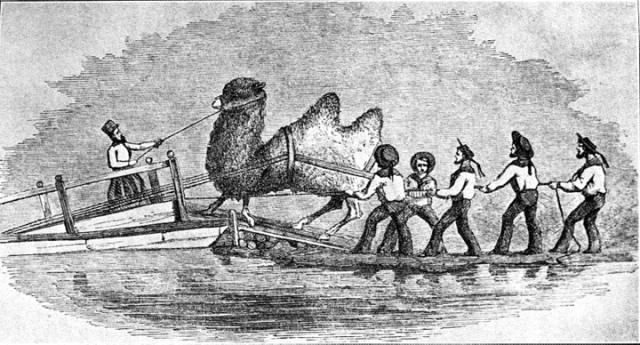

On Feb. 15, 1856, the USS Supply headed for Texas. On May 14, the camels reached Indianola, Texas, and on June 4, Wayne began marching the camels to San Antonio, Texas. They arrived almost two weeks later.

CAMEL EXPERIMENTS

Given some deaths and births and a new purchase of camels arriving on the USS Supply on Feb. 10, 1857, the Army had 70 camels for the experiments. The camels were stationed at Camp Verde, Texas, where Soldiers and civilians were trained on camels for military use.

The camels proved to be successful in tests around San Antonio and Camp Verde and in several long and trying survey and reconnaissance missions in the southwest. In particular, camels needed little forage and water compared to mules. They could also ford rivers much easier without a fear of drowning and could carry heavier loads.

Forage often could be obtained in the desert as camels would eat food growing along routes that mules and horses would not. This helped ease the burden of transporting forage for the animals.

Camels also did not require shoeing like horses and mules did. They could climb mountain trails better than wagons and would not get stuck in the mud like the wagon wheels used by the Army at the time. The only downside was that the smell of camels appeared to bother the horses.

In 1860, then Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee used camels on a long-range patrol. He provided great reviews of the camels' capabilities, but information provided from his reviews may have been ignored with the onset of the Civil War.

CIVIL WAR ENDS THE EXPERIMENTS

Early in the Civil War, Confederate forces captured Camp Verde along with the resident camels. However, they did not use the captured animals for any major operations during the war.

A second camel flock that had been moved to Camp Tejon, California, remained in Union control. It was transferred to different posts throughout the war because no one could think of a mission for them.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, unaware of the camel experiments, saw the camels as useless and ordered them to be sold. The camels in California were sold by the end of the war. The remaining camels that were recaptured from the Confederates at Camp Verde were sold in 1866. Many camels were abandoned by new owners or escaped into the wild.

In 1885, Douglas MacArthur (who went on to serve 52 years in the military and hold the top position in the Army) was living at Fort Selden, New Mexico, and recalled seeing a camel. Reports of alleged camel sightings continued to be recorded until the 1940s.

A likely reason for the failure of the camel experiment was that the Civil War was a very mule- and horse-centric conflict. Most of the war was also in the east, where railroads, rivers, and roads were the dominate supply routes.

Another reason the camel experiment failed could have been that its major supporters were Confederates. Jefferson Davis was president of the Confederacy, and Henry Wayne was a brigadier general in its army. The Union likely ignored the great camel review written by Robert E. Lee in 1860 because of his association with the Confederacy as well.

If not for the Civil War and the broken continuity of camel advocates, camels may have been fully integrated into the Army in the southwest. They proved their worth and would have been a valuable asset in the numerous garrisons and conflicts in the west following the Civil War.

Given their proven abilities, camels would have improved logistics in the rugged southwest during conflicts and garrison resupply operations. The success of camels in French, British, and other armies throughout history appears to validate the Army camel experiments. Its failure was not caused by the camels' lack of capabilities.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

James A. Harvey III is a military operations analyst and the operations officer for the Army Materiel Systems Analysis Activity Condition-Based Maintenance Team at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. He is also a Logistics Corps lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve. He holds a bachelor's degree in political science from Towson State University and a master's degree in military studies with a concentration in land warfare from American Military University. He is a graduate of the Ordnance Officer Basic Course, Transportation Officer Advanced Course, Combined Arms and Services Staff School, and Intermediate Level Education Common Core Course.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the May-June 2016 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Discuss This Article in milSuite

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing