In 1981 many memorable historical events happened such as the U.S. and Iran signing an agreement to release 52 Americans hostages after 444 days in captivity. President Ronald Reagan was also shot and wounded by John Hinckley III during this time. But, one of the most significant events was the discovery of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a rare lung infection which was affecting gay men in Los Angeles.

This became the first official reporting of what would become known as the AIDS epidemic, according

to www.aids.gov.

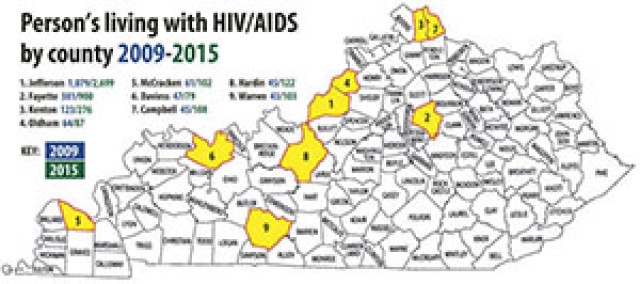

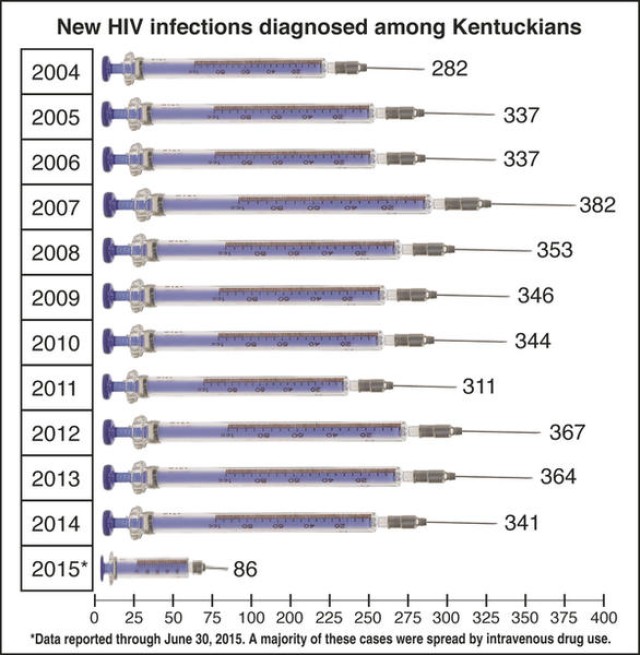

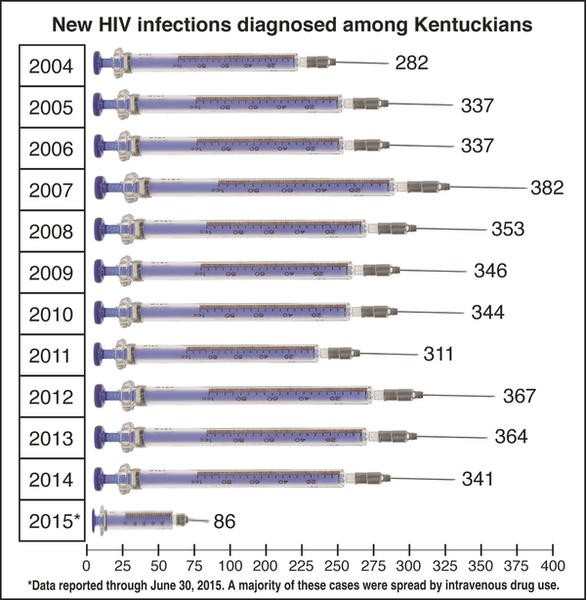

Although HIV has gone from the No. 1 killer among ages 16-25 in 1995 to the No. 6 killer, newly reported cases in Louisville and southern Indiana are on the rise causing concern in the medical and law enforcement communities.

According to the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, around half of the state's 9,300 HIV cases, as of June 2014, were Louisville residents.

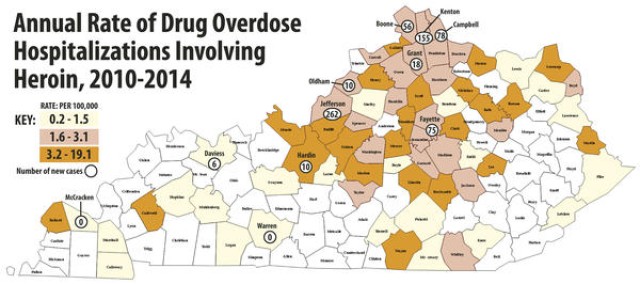

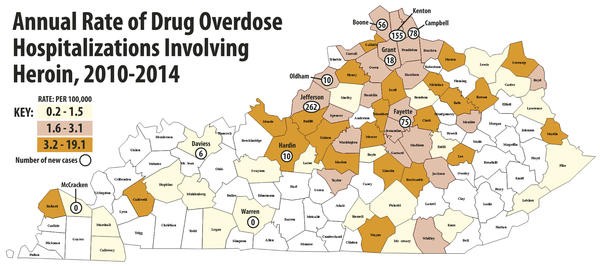

Recently, an HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, caused from a new heroin-use-epidemic, has brought the issue of AIDS and HIV back to the forefront of social discussion. Scott County is located 30 miles north of Louisville.

The concerns of law enforcement differ from that of medical personnel--part of the reason for the rise in cases is from the use of shared needles via drug use.

Dr. Will Cooke of Foundations Family Medicine in Austin, Indiana, said in an interview with the Gold Standard, there have been 189 people who have tested positive for HIV in his community. He added that most of those tested positive are IV drug related and more than 80 percent are coinfected with hepatitis C.

"Waiting until after an outbreak happens is not protecting the public and not the best public health policy," explained Cooke. "It's too late. Viruses and drug use do not respect county boundaries. We need comprehensive, statewide or better yet nationwide response to this urgent issue. We are losing lives.

"The single best way to prevent the spread of HIV and hepatitis C is to treat the disease. That's what we are doing. All additional strategies are great but mean nothing without treatment."

But the overall concern for the situation is because all the education, safety and personal responsibility training conducted since the mid-'80s needs to be revisited as today's youth have forgotten the deadly lessons of the past.

In the beginning AIDS was a death sentence.

Dr. John Van Arsdell, a former internal medicine doctor at Fort Knox's Ireland Army Community Hospital, who is currently an internal medicine and infectious disease physician at Kentucky One Health, said when he began practicing internal medicine in 1985 doctors read reports that AIDS was in all body fluids and no one knew the facts.

"It was a very frightening time," he explained. "It wasn't until that year we were able to do a lymphocyte panel to tell somebody's T cells. We couldn't do viral levels because that was still years away in 1985 and 1986."

In 1986 AZT, a new drug at the time, required the patients take two tablets every four hours. But in the wrong combination AZT would be as hard on the body as the virus.

"(They were taking) 12 tablets a day, (and it) was just brutal to those kids," Van Arsdell said, but, "it was like any other drug in the right dose."

He added it was and still is a great drug.

"We actually found out less than half of that was the ideal dose," said Van Arsdell.

Van Arsdell added that 24 of his 27 patients died in one year and the other three followed the next year.

Everybody died during those early days, he said.

In the 12-a-day regiment it was extremely toxic to the bone marrow and caused, in some cases, profound anemia. Some of the patients needed blood transfusions so they could simply take the drug.

Van Arsdell recalled how one of his patients was so sensitive to the drug that he required many transfusions.

"When I (began) practicing infectious disease in 1988, I had one young man (who) was so sensitive to the drug, he required so much transfusion, that he finally said, 'no, I'm not doing it…I will talk to you in the morning,'" he said about his former patient.

After much discussion, he finally relented and told Van Arsdell he would come into the doctor's office the next day.

"I talked to him at 8 o'clock that night and the next day he didn't come," said Van Arsdell. "By noon (that day) my medical assistant … knew something was wrong. She called the police and they went to his apartment in the (Louisville) Highlands and he was dead."

In 1996 Dr. David Ho, an HIV/AIDS researcher, advocated for a new strategy for treating HIV--a three-drug regimen. From that point on if you treated patients with appropriate combo drugs, they stood a chance of survival.

"If you lived to 1996 when the protease inhibitors were released, then the likelihood (is that) you are still alive today," explained Van Arsdell. "When the cocktail was recommended (it) used two drugs that worked in a different way on the virus, plus (adding) the protease inhibitors. The protease inhibitors were the monster guns. People actually started getting better, you started seeing improved T counts, you could get viral loads undetectable, which is where they needed to be. You could keep people alive."

But, Van Arsdell said that doesn't mean a person is HIV negative because the HIV antibody is still in the bone marrow.

It's important to note, the disease hasn't been relegated to the civilian community.

Soldiers are required to take an HIV test every two years, as well as when they deploy and when they have a permanent change of station overseas, said Maj. Craig Meggitt, the former assistant chief of Preventive Medicine at Ireland Army Community Hospital.

Military personal who engage in risky behavior aren't immune--and can lose more than their good health.

Meggitt added that Soldiers are also tested if a primary care provider is aware of other risk factors or risky behavior.

"If we see someone who's tested positive for an STD (sexually transmitted disease) we will test for HIV as well," explained Meggitt.

Once upon a time, testing positive for HIV meant the end of a military career. But with the new drugs and AIDS awareness, regulations have changed.

Once a Soldier takes an HIV test and the results are positive, Meggitt said the Department of Defense has an initial screening assessment that tests for antibodies for HIV. If it's negative then the service member is HIV negative. If it's positive more testing is done to include a Western Blot, which looks for at least five different markers from the HIV virus, he said.

"Your body has produced antibodies to five different markers (and) they all have to be positive to be a positive test," explained Meggitt. "When I get a result back which says this person is HIV positive we are certain they are HIV positive."

When that happens Meggitt contacts the Soldier's chain of command.

Betty Walker, an administrative attorney with Fort Knox's Office of the Staff Judge Advocate, said the Soldier's chain of command will counsel the exposed Soldier about the restriction to which he or she must adhere.

"Restrictions such as practicing safe sex, telling potential partners and not donating blood," said Walker. "Not adhering to these restrictions can result in UCMJ (Uniform Code of Military Justice) punishment for the Soldier and/or voluntary discharge, per AR 600-100."

Meggitt said they have to involve the Soldier's UCMJ authority, the person who can enact UCMJ actions against them in the future.

"This is in preparation for the initial counseling we are going to do," Meggitt explained. "We call behavioral health and tell them we are going to counsel somebody who's newly HIV positive and we need (them) on standby in case we need (their) help. This is going to be a very traumatic experience for this person and we make sure we have a chaplain available, who we can call up on a minute's notice, who can sit down with (the) Soldier if (he or she) wishes."

He added that they arrange with the Soldier's chain of command and the UCMJ authority for the Soldier to be at the hospital on a specific date and time.

"In general we do this as quick as possible," Meggitt said. "We can get (this) done within 24 hours. They have an infectious disease that is potentially very harmful for your health and even fatal in some cases. We don't want them to infect anyone else, and we want to make sure they know right away."

Meggitt pointed out that a doctor must do the initial counseling. The counseling form goes through everything the Soldier has to understand with his/her new diagnosis and it emphasizes more of the medical side of what they need to know, like not being able to donate blood or organs and notifying medical personnel if they are having a medical procedure.

"The two big ones we emphasize after you tell someone they are HIV positive (is) 100 percent partner notification, 100 percent condom use--this is not negotiable," said Meggitt. "This is something that (will get a) Soldier into trouble, this is something that will get (a) UCMJ action brought against them."

Once Meggitt finishes his counseling, he will ask the Soldier if he/she has any additional questions. If everything is OK he will then contact the hospital's public health nurse. The public health nurse will oversee the commander's counseling and the Soldier is also informed about the mandatory appointments every six months with an infectious disease doctor.

The public health nurse will also ask the Soldier to contact all of the sexual partners she or he had in the last six months to notify them about the positive results.

"We don't name the person, but we do follow up to make sure they get testing as well," Meggitt said. "Once we finish all of our counseling (the Soldier) essentially (goes) back to their normal duty day being a normal Soldier.

"There used to be more restrictions in place that have loosened a little bit as long as you continue to be healthy. You can't deploy (and) you can't serve overseas. Most countries in the world have travel bans for people with HIV… Even the United States had a ban until 2009."

Meggitt pointed out that as long as a Soldier remains healthy he or she can remain in the Army and attend military courses that are needed to further their career.

He added that the old policy had limitations on the number of weeks a course had to be for a HIV Soldier to attend. Now, he or she can attend as long as they are healthy. But, an HIV-positive Soldier cannot attend civilian training, like graduate school.

"For military schooling Soldiers (who) are infected and determined to meet retention standards are eligible for all military professional development schools, NCO (noncommissioned officer), Captain's Career Course (and) intermediate level education," explained Meggitt. "HIV-infected Soldiers may also attend formal military training required from them for reclassification for a new MOS (military occupational specialty), award a skill qualification, or additional skill identifier.

"If an educational program would require you to stay in the military longer, you're not eligible. The regulation changed in 2014."

Although there have been HIV-positive Soldiers on Fort Knox, Meggitt said he doesn't see a lot of cases. In fact, he said the installation has an average of less than one new case a year. He also said there is nothing in a Soldier's record which states he or she is HIV positive.

"Someone at HRC is aware so that you don't come down on orders to PCS overseas," he said. "(The) chain of command (and) the company commander know and it's his (or her) discretion who else has to know. (The commander) has a record of that counseling that has to be under lock and key--no one should have access to that but (the commander)."

If an HIV-positive Soldier PCSs he or she has a case manager in the hospital. They have to tell their case manager within 30 days of leaving. The case manager will tell the receiving case manager that the Soldier will report to them at their new duty station. If the Soldier fails to do that they can be prosecuted.

"The case manager is the person who's going to be monitoring and make sure they keep up with their medical appointments and keep track of what's going on with (the) Soldier," Meggitt noted.

Although Fort Knox has less than one new case of HIV each year, Meggitt said that's not the average with summer cadets, which is more than one case during the summer.

He said when cadets arrive on Fort Knox they are processed through Ireland and take a screening test which isn't very specific for HIV. Since it isn't HIV specific, Meggitt said a lot of the screening tests are positive, which is why they don't solely rely on the test. Follow-up testing takes two weeks. He added, by the time the hospital receives the results the cadets have completed half of their summer training.

"We follow the exact same procedures, and since they are not Soldiers they are not subject to UCMJ," Meggitt said. "We let them know because most states have partner notification requirements. We need to let them know that they will be subject to those laws when they go home."

Meggitt said once a cadet is notified he or she is sent home and disenrolled from the school's ROTC program because they can't pick up the requirement that they serve for a certain amount of time and they can't receive a commission.

"For me having to do an HIV notification is the worst part of my job," he said. "It is heartbreaking in those cases even more so than the active duty (because) they put so much into ROTC. In a lot of cases they thought they were going to be active duty and find out, 'hey you're going home. You are going to be disenrolled from ROTC,' and whatever education you have left to get your degree you're going to have to do it on your own."

Risky behavior includes sharing drug paraphernalia, multiple sex partners, using drugs, and having unprotected sex.

Meggitt said education and understanding the facts and myths are key to protection against HIV.

For more information, visit http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/.

Social Sharing