Staff Sgt. Kristen Totten has something everyone wants in their veins: the gift of life.

But until the medical lab technician's O positive blood is deemed safe for public use, her universal lifeline remains a party of one--all because she lived in Germany during the 1980s when European cattle were diagnosed with Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, a fatal brain disease that could be transmitted to humans via the food chain. The result: all military personnel, civilians and dependents who spent six months or more on European-based military installations from 1980 to the mid-1990s are ineligible from donating blood, per the Center for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration.

"It's frustrating that I can't donate since I have the blood type everyone wants," she said, joking about her "mad cow disease" tainted blood, yet understanding that it's all about safety even though there's only a minuscule chance her blood contains the dormant gene associated with the European contaminated meat products. "I do understand that we need to have the best possible product for people, and if I or my kids ever needed blood, I would want it to be as clean as it could possibly be."

Totten said she hopes a test will eventually clear her blood, but for now, she said she's content in her role as cheerleader and quality control over at the Robertson Blood Center (RBC), one of 21 blood-collection centers in the Armed Forces Blood Program that provides quality blood products for service members, veterans and their Families in both peace and war.

"It's really important to me that we do the best we can here and make the best products we can because the people who need it are really hurting," she said, adding how she witnessed the power of blood in keeping trauma patients alive during her time in Iraq. "What we do over here might seem mundane and tedious, but we're helping save lives in a background sort of way, because without our diligence in making good products, a lot of people wouldn't be alive today."

According to the American Red Cross, "O positive blood is in high demand, trailing only O negative blood, which is used in emergencies when there isn't time to type a recipient's blood. Those who are O positive can donate blood to any of the other positive blood types, which means that 84 percent of the population can receive their red blood cells; 100 percent of the population can receive their platelets; and 45 percent of the population can receive their plasma."

Totten, however, has only two options if she ever needs blood: O positive or O negative, the latter of which is in short supply over at Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center's Transfusion Medical Service, according to its medical director, Maj. Molly House.

"Those with O negative blood are universal donors, and that's the blood we use during emergencies," said Major House, adding how critical it is for donors with O negative blood to "save a life," especially because donations always drop off after the holidays.

"January always has been a challenge in replenishing our O negative supply," said Melissa Showman, a medical technician at RBC.

Showman said one of the reasons for the donation drop during the first of the year is because people tend to donate before the holidays. There also is a 56-day recharge period for donors, as well as a shelf life of 45 days for red blood cells and five days for platelets.

She said it's not unusual for 40 pints to go to trauma patients, which can easily deplete the blood supply.

All donations at the Robertson Blood Center go to service members, military Family members and veterans. The center also is required to provide about 40 units a week to the war effort.

"What makes this challenging is that there are percentages of blood within the population with the same blood, so we actually have to collect more to get that quota," said Maj. Ronnie Hill, director, RBC.

Another obstacle is Fort Hood's deployment rate.

"Soldiers would deploy and come back home and then within the 12-month time period where they could donate, they would be deployed again," said Hill.

That's the reason why Staff Sgt. Joseph Farrand began a push for donors at the III Corps and Fort Hood Noncommissioned Officer Academy.

"There was a bunch of 18-20-year-olds with no combat patches at the academy," he said, adding that he first started donating blood when he was 18. "I thought 'fresh blood' when I saw them, and I made sure these young, driven Soldiers understood that their blood would only go to Soldiers or their Families. I also stressed that if an installation doesn't get enough blood, it has to buy it."

Helping other Soldiers was one of the reasons Pvt. 1st Class Josephine Wickizer, 2nd Brigade, 1st Cav., was recently over at Robertson Blood Center donating blood.

"Even though I am back here in the rear, I can still help our Soldiers on the front lines," said the first-time donor who admitted she was a bit nervous. "I know I would want someone in return to do it for me -- that is my biggest thing."

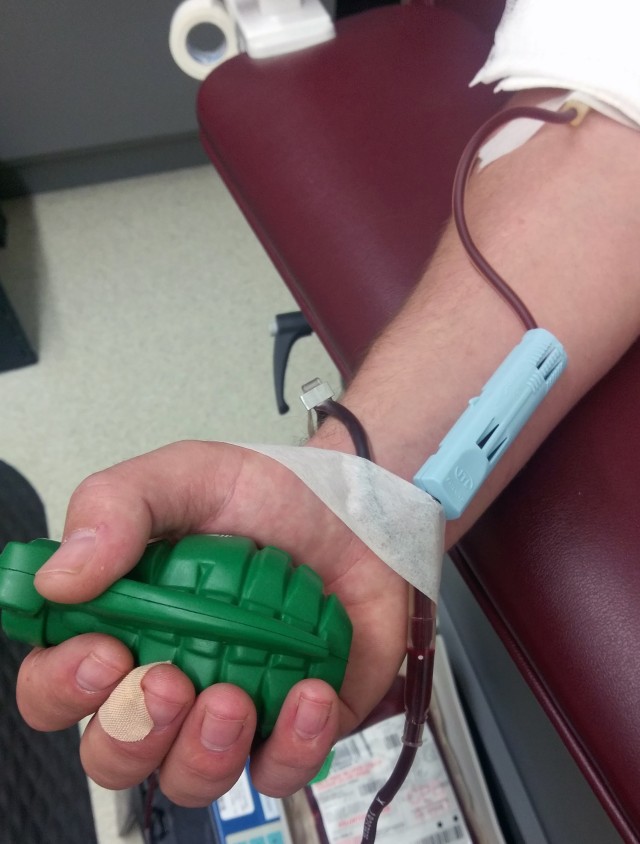

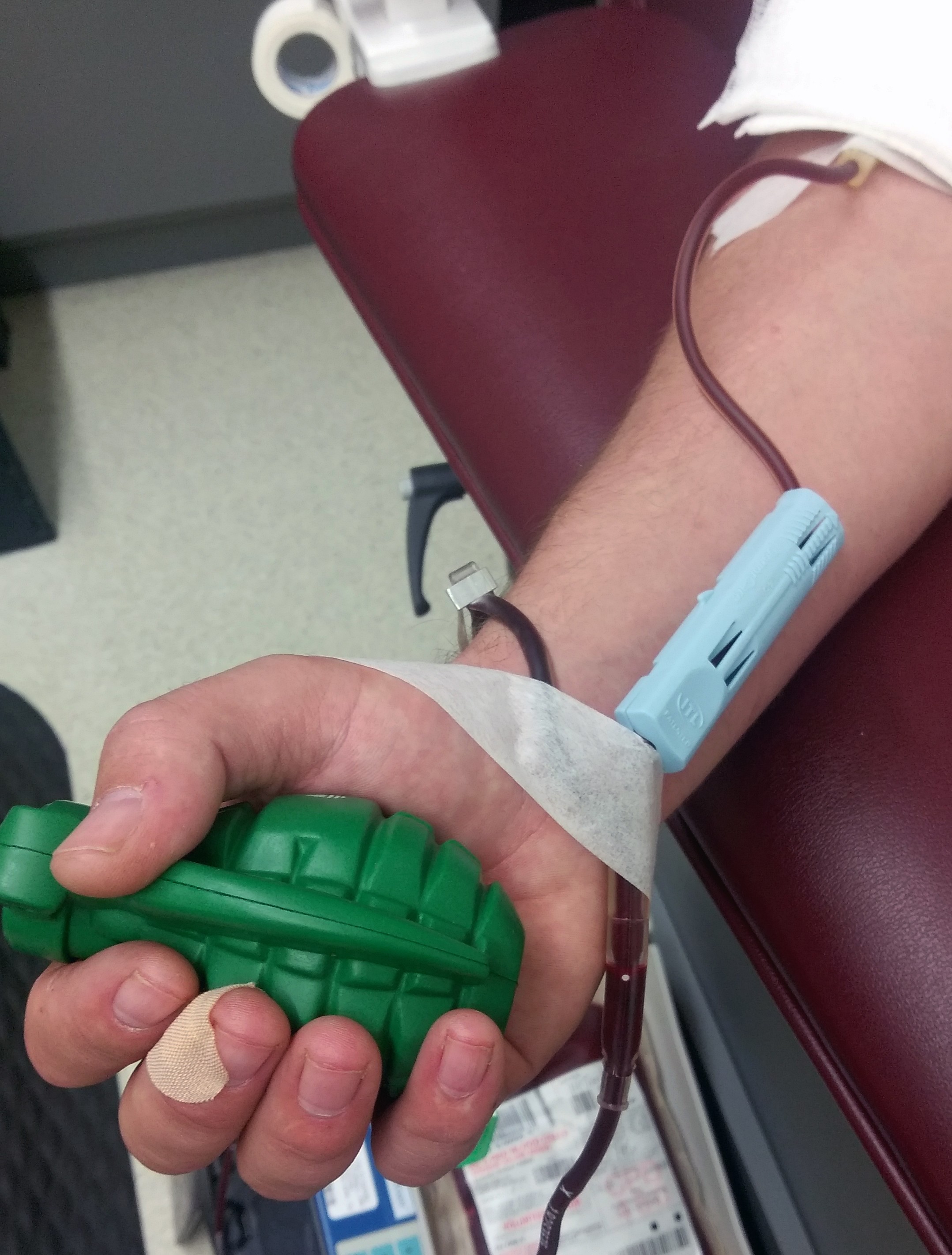

When donors walk into the clinic, they are interviewed and vetted said George Barnard, one of the center's phlebotomist. After the interview, the blood-collection process can take anywhere from four to 15 minutes.

The retired Soldier said seeing Soldiers like Wickizer donate her time to give life to others warms his heart.

"It's a good feeling to see them taking the initiative to give back," he said.

Even though Spc. John Perkins, who also is from 2nd Brigade, 1st Cav., doesn't like needles, he admitted it felt good to help someone.

"It wasn't as bad as I thought," he said, although he chuckled at Barnard when he told Perkins he had a great vein. "I thought he was way too excited about my veins."

But donating blood, according to Showman, is not about the size of the vein, but about the size of the heart.

"It can be a little intimidating if you are afraid of needles, but if you focus on what you are doing and why, it will help you get through it," said Showman. "You are saving a life by spending five minutes in a chair with a needle in your arm."

Social Sharing