MEMPHIS, Tn. (October 29, 2015) - The 2015 U.S. Military at West Point Civil Rights Staff Ride was profoundly different from those of the past two years. Previously, Cadets struggled with the widespread belief that race no longer mattered in America and that the presidency of Barack Obama was proof of a color-blind society.

This year was the first time since the dramatic and seemingly unending events involving violent police confrontations with African-Americans that raised popular awareness that racial intolerance was still lingering in America.

The Staff Ride is a component of an intensive Department of Law course combining interdisciplinary study in the classroom with a two-week journey throughout the American South to understand diversity and immerse cadets in the culture of the Civil Rights Movement.

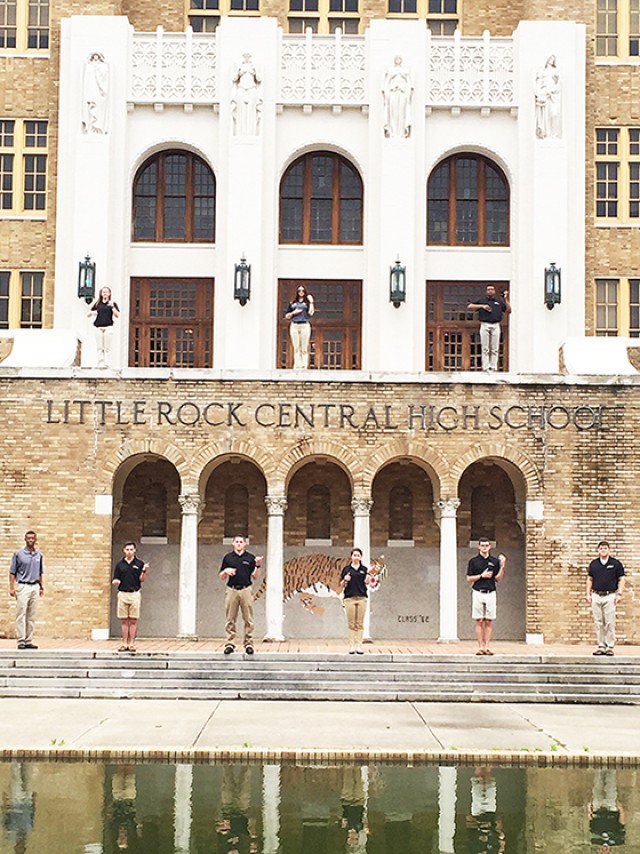

Cadets would also study current issues including intolerance in the areas of education, criminal justice and environmental justice. Cadet sophomores Gabriel Bann, Alexander Combs, Nikaila Glassy, Madeline Higgins, Jason Hug, Maria Kruegler and Morgan Landers were selected to participate.

The Staff Ride was sponsored by the West Point Center for the Rule of Law and the Departments of Law and History; and was funded entirely by gift funds. Escorting Cadets on this exciting journey were Lt. Col. Winston S. Williams, from the Law Department; Capt. Daniel Sjursen, from the History Department and Professor of Law, Dr. Robert J. Goldstein, who has led the Staff Ride since its inception in 2013.

The course syllabus included the Pulitzer Prize-winning bestseller "Devil in the Grove," by Gilbert King documenting the story of four young black men accused of raping a white woman in Lake County, Florida, in 1948. King traveled to West Point to speak with cadets. The hero of the story, NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, would risk his life to defend the boys. The future Supreme Court Justice would travel by train from New York to Jim Crow Florida. There he was a second-class citizen, unable to stay in a whites only hotel or eat in a whites only restaurant.

The Staff Ride would follow in Marshall's footsteps. The neighborhood surrounding the Leesburg African-American Museum looks much as it did when Marshall first arrived. Ramshackle homes in this clearly segregated community typify what it means to be on the "other-side-of-the-tracks."

Nevertheless, Cadets were warmly greeted by the Museum's curator and amazed as the building filled with invited neighbors anxious to talk with Cadets about the history of the Groveland case. In the room were relatives of the four boys as well as local community leaders. All were intent on retelling the story and adding their own personalized epilogues to it.

They also talked about Lake County today and the challenges that their community faced as gentrification blossomed around them. In the old Lake County Courthouse where three of the Groveland boys were beaten for a confession, and where they were later tried and convicted, the current sheriff hosted a program for Cadets with community leaders.

At Central High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Cadets focused on equality in education. There they were welcomed by Principal Clarence Sutton Jr. and a gathering of school officials and community members eager to tell their story. Cadets were introduced to the story of Tuscaloosa's Bloody Tuesday, when African-Americans protesting separate drinking fountains were beaten and arrested as they marched to the Tuscaloosa Courthouse.

According to Sutton, Central High is 99 percent black. Peering out of the back door of the school, he pointed to an adjacent house and noted that the children in that house are white and they are bused to a majority-white school out of the neighborhood. This was a surprising revelation. Even more troubling was that the re-segregation of the school came about after the federal court released the school district from federal oversight.

Environmental Justice issues are a continuing threat to the lives of residents in the poor rural South. In the "Black Belt" of Alabama, an area originally named for its rich soil, is now known for its profound poverty, these issues threaten the health of its largely African-American population.

Catherine Flowers of the Equal Justice Initiative showed Cadets a pervasive problem in Lowndes County. Because of the nature of the soils in the "Black Belt," drainage is impaired. In many poor communities without publicly operated treatment works, it means that sanitary waste must be dealt with by individuals. In other words, homeowners must construct a sanitary sewer that will handle both the solid and liquid wastes.

For the poor, it has come to mean a pipe leading from the toilet to a hole-in-the-yard where solid and liquid waste will accumulate until the liquids leach into the soil and the solids settle. The "hole" that Cadets were shown was a pool of waste. That in-and-of-itself is a problem, but there is an even more compelling health threat here--mosquitoes breed in this pool of muck and diseases are transmitted by those insects.

Flowers noted that this problem is pervasive in the "Black Belt," and that tropical disease experts are attempting to determine if health problems in this region are related to the mosquito vector.

In Gainesville, Georgia, the Cadets talked about the disparity in justice between the poor and the wealthy in America with Public Defender Travis Williams. He was one of three lawyers featured in the HBO documentary "Gideon's Army." Cadets had read "The New Jim Crow," by Michelle Alexander, which documents the disproportionate incarceration of African-Americans in the United States. One reason for this, Alexander noted, was the difference in legal defense offered to the poor by overworked public defenders as compared to the private attorneys available to less indigent defendants. Williams is a public defender bucking that trend. In his offices in the Hall County Public Defenders, Williams and his colleagues made clear the pressures they were under to provide counsel to impoverished defendants who need their help when they are entangled in the criminal justice system.

On their last stop, Cadets visited one of the very few places where the rule-of-law triumphed over discrimination and racism in Clinton, Tennessee.

In 1950, a local group had unsuccessfully sued to allow African-American students to attend Clinton High School. The team of lawyers included Thurgood Marshall. After the 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the Clinton School Board was ordered to end segregation. Almost uniquely, Clinton created an integration plan and without incident prepared to enroll 12 African-American students in the fall of 1956.

Segregationists saw the potential precedent of integration at Clinton High School as a threatening precursor toward a national move to end segregation, they descended on Clinton en-mass to violently disrupt the process.

Again remarkably, the community unified to ensure that the rule-of-law would be upheld. Community members, many of them military veterans, organized a protective force. School leaders organized monitors to ensure that the African-American students were not harassed, and uniquely, the Governor of Tennessee sent State Police and National Guard to support the integration of Clinton High School.

The West Point Civil Rights Staff Ride has taken the concept of the staff ride to a completely new level, leveraging the Army's reputation for social justice and innovation and using cultural immersion to create a unique learning environment for Cadets.

In the words of several Cadets, it was a life-changing experience.

Social Sharing