ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, Md. - Frederick Ryan decided to enlist in the Army shortly after receiving his draft notice in 1965. He nearly didn't make it in. Army officials told him that on paper, he did not exist.

Ryan was born in the Bronx, New York. He lived New York, Vermont and Pennsylvania as a child and ended up in foster care in Essex, Maryland where he grew up. He took his step-father's name, Gant, when his mother remarried, but remained in foster care. When the time came for him to join the service, and the only certification he had was from his step-father, the Maryland social services had to step in and obtain documents from the state and from his birth mother. He officially took the name Ryan before enlisting.

In the Army, Ryan took the hard road. After basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, he trained as an 11B Intrantryman at Fort Benning, Georgia, and then was shipped to Fort Lewis, to await movement orders to 'Nam. His unit was transported by ship for the 21-day journey that ended in Cu Chi, South Vietnam.

"I loved the water so it didn't really bother me. But some guys didn't take it well," he recalled.

A fully-trained demolition specialist, the 19-year-old Ryan was assigned with the elite 5th Special Forces Group. They hit the ground running and moved constantly; reconnoitering, scouting, harassing and engaging in firefights with the enemy. Much of their missions focused on the immense tunnel systems throughout the region that were utilized by Viet Cong. Ryan said he blew up bridges, tunnels and anything else that needed demolishing. This new world of beautifully lush jungles that hid innumerably deadly possibilities was no place for teens, and he grew up fast.

According to the Department of the Army "Vietnam Studies, U.S. Army Special Forces, 1961-1971," between May 1966 and May 1967 there were wide-ranging changes and improvements in the operational employment of the Special Forces. Mobile guerrilla forces were formed and operated in enemy-controlled zones; operational directives specified that camp operations begin and, where possible, end in the hours of darkness. This tactic was based on the realization that the night belongs to him who uses it. This resulted in a substantial jump in the number of the enemy killed in the last quarter of 1966.

"We were in the jungle the whole time," Ryan said. "We stayed pretty busy during the night too, setting up perimeters, going on recon missions. We saw action almost every day. But when things got quiet, sometimes the fear would come. But you dealt with it or you put it away. You didn't have time for it."

He said he survived that first tour thanks to the "great bunch of guys" he was fortunate enough to work with. Scouts, gunners, snipers and more, all were thoroughly trained and skilled in their art. He said they took pains to learn each other's skills. Trusting in and having your brother's back were essential elements to surviving in a place where no one else in the world could help you, he said.

"You either got it done or you didn't. Everyone had their role and everyone knew what the other was capable of. What's more, we knew where to pick up where the other left off if the worst happened. We were more than brothers, if that's possible. "

Out of a close-knit group of 11 young warriors during Ryan's first tour, only three made it home.

Ryan did get to enjoy R&R at Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia during that first tour. It lasted one week.

"It was good, I needed that break at that time," he said.

He was wounded, taking shrapnel in his back, during that first tour but said it was "nothing big."

Then while "reconning," he was shot in the shoulder and was medevaced to a field evacuation hospital He was lucky, the bullet passed through and he was hospitalized only three weeks. He returned to the jungle.

"They sewed you up and sent you back out there," he said.

Four months later, while on a search and destroy mission, he took a bullet through the shoulder during a firefight. Again, it passed through.

Ryan said he was angry during that hospitalization.

"I just wanted to get even. That's the only thing that was on my mind. I wanted to get back out there and back up my brothers," he said.

Ryan signed on for a second tour at the end of the first one. He said for a break he received two days R&R between at an Air Force base but even then, "flew out with them on spotter missions."

He and his buddies, all advisors now, were split up among the growing American forces with some going to the 1st Infantry Division while others went to the 25th, he said.

"I was an E-5 [sergeant] by then and in a leadership position, so I led a lot of search and destroy missions," he said.

He spent much of his second tour "up around the DMZ and in South Central 'Nam and went to Laos a couple of time."

Ryan avoids the specifics of their missions, only acknowledging that fellow Soldiers made it bearable.

He returned to the states in July 1967, first arriving in Georgia for debriefing and then to Fort Meade for just over a week before landing in Fort Drum, New York where he was assigned to a tank unit.

"They made me a tank commander and I'd never even seen a tank before," he said. Ryan "mustered out" of the Army Dec. 15, 1967. He returned to Baltimore but said he found the city less than welcoming.

"I couldn't even thumb a ride; nobody would pick you up in uniform. It really ticked me off. After all I'd been through - fought and nearly died for this country - and to come back to that," he said.

Finding employment was no easy task, either.

"For three months I tried to find work but nobody wanted you if you were a veteran. I finally got hired as a machinist when I left [my military service] off the application," he said.

The job, however, didn't last long. Ryan said too many sounds in the manufacturing environment "took me back to 'Nam."

"They had whistles for this and sirens for that. It all sounded like artillery coming in," he said. "I had to get out of there. They told me I could come back any time I wanted but I never did."

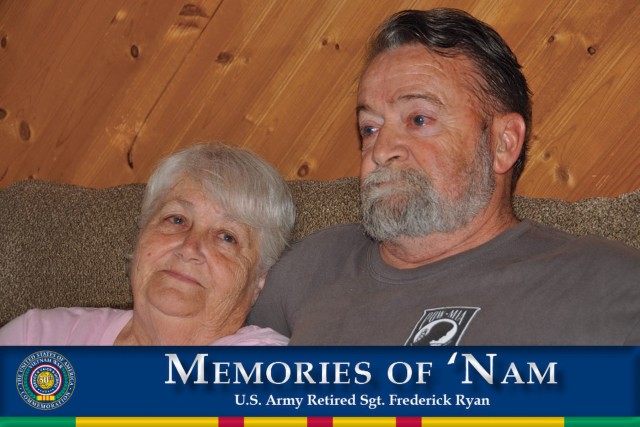

The brightest spot in his life, Ryan said, was his childhood sweetheart Eileen. They had been playmates since he was 8-years-old and she waited for him through 'Nam and through his readjustment period. They married in 1970 and raised three children together.

Forty-five years later he still is dealing with the demons he kept at bay while in 'Nam. He and Eileen live quietly in Abingdon. A member of American Legion Post #17 in Edgewood, Ryan regularly attends local Memorial and Veterans Day ceremonies. He also is a regular at the Veterans Outreach Center in Aberdeen, where he gets help confronting the demons from the past.

Eileen Ryan said it's been a trial for her husband.

"It took so long for them to finally identify his problem as PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]," she said. "He's on medication now and it does help. But sometimes at night, he's still scared."

Ryan gets misty when he thinks back on the kid who arrived in 'Nam in 1965 and the man who left there in 1967.

"I was a whole different person, he said choking back tears. "I saw a lot of killing; I lost a lot of friends. There was no way to prepare for that. They tried to make you ready with training but there's nothing like getting shot at."

He said one thing he'd like to do is to meet and chat with modern-day Soldiers, particularly Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.

"They're the real heroes," he said. "I know it was two different kinds of wars but it would be nice just to be in their company. It's still a brotherhood. I know that much hasn't changed."

#########

Like any other war, Vietnam produced an array of veterans. When the conflict ended, some veterans opted to continue service in the military while others returned to civilian life. Some returned with life altering wounds - physical and psychological - while too many others, who never came home at all, remain among the Missing in Action.

On the surface, the veterans of the Vietnam War faced the same challenges as veterans of other wars, except for one glaring difference: they were vilified by American society like no other generation before or since.

Today, nearly 50 years after the war's end, the veterans of Vietnam are in their 60s and 70s. The passage of time has cooled the tempest of indignation that shrouded their homecoming and an ambiance of repentant thanks thrives in its wake. Many still do what they can to serve this nation.

This article originally appeared in the "APG News" as part of an ongoing, multi-year series hailing the service members and civilians who served the nation during the war in Vietnam. Giving a voice to local Vietnam veterans, it is through their stories that we honor their service and sacrifice, and offer a long-overdue "Welcome Home."

The "APG News" is the weekly newspaper produced at Aberdeen Proving Ground, an Army installation located in southern Harford County, Maryland, nearly midway between Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. APG is recognized as one of the world's most important research and development, testing and evaluation facilities for military weapons and equipment, and supports the finest teams of military and civilian scientists, research engineers, technicians and administrators.

For more information about the series or the veterans featured, contact "APG News" Editor Amanda Rominiecki at amanda.r.rominiecki.civ@mail.mil.

Social Sharing