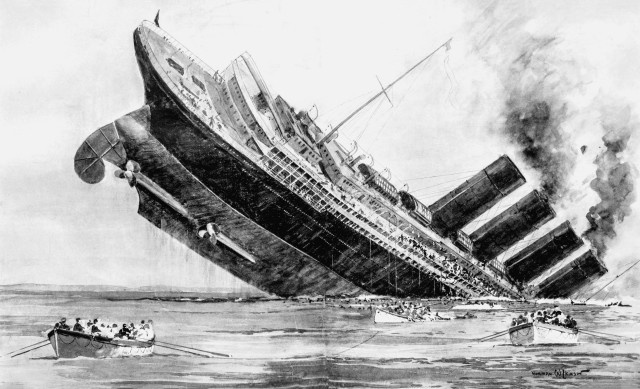

It was just after 2:00 p.m. when spotters saw the track of a torpedo heading for the starboard bow. The captain of the RMS Lusitania, William Turner, felt his ship shudder as the torpedo struck. A moment later, as confusion began to spread through his ship, he saw the emergency lights on the bridge's signal board flare up as a second and much greater explosion ripped through the bow of the great ocean liner. Convinced his ship was doomed, Turner gave the order to abandon her. What followed was 18 minutes of indescribable chaos and disaster. The heavy starboard list, quickly becoming over 25 degrees as the bow took on water, made it virtually impossible for passengers to get into the lifeboats on the starboard side. In contrast, those lifeboats on the port side swung inward to the boat deck. Some of these were released and slid their way down the deck crushing anything in their paths, while others were dashed against the side of the ship as efforts were made to lower them. And then it was over, as boats rushed from the Irish coast to search for survivors. Of the 1,962 passengers and crew on board, only 761 survived. Among the dead were more than 120 Americans.

The sinking of the Lusitania, one hundred years ago on May 7, 1915, marked a turning point for the United States regarding what is now called World War I. While it did not immediately lead to this nation entering the war, it hardened the attitudes of many towards Imperial Germany and set the stage for America's eventual intervention. It also highlighted the problem of civilians taking risks to enter war zones underscored today by the recent deaths of noncombatants in the Middle East and Ukraine.

Launched in 1906, the Lusitania, along with her sister the Mauritania, was the pride of the Cunard Line company. When she sailed on her maiden voyage in September 1907, the Lusitania established herself as one of the fastest luxury liners in the world, earning the accolade of the "Blue Riband" for the fastest transatlantic voyage no less than four times. While she would soon be rivaled by the White Star Line's Olympic-class ocean liners (which included the Titanic), these were built more for luxury than speed. If one wanted to cross the Atlantic in style and haste, the Lusitania and her sister Mauritania were unmatched. Indeed, the Mauritania set a speed record in 1909 that remained unbroken for 20 years.

With the onset of hostilities in 1914, many British merchant vessels were pressed into service as Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMCs). These boats, typically equipped with sufficient firepower to place them on par with a light cruiser, were set up to ward off raids by German vessels, particularly submarines. In the early days of the war, German submarines would surface before sinking a merchant ship with its deck gun, doing this partly because they lacked confidence in their torpedoes and also due to archaic laws of the sea which called for unarmed boats to be warned before being captured as prizes. Boats like AMCs could surprise the surfaced submarine with its armament and damage or sink it. AMCs were developed as an ad hoc measure, largely because British war planning had failed to account for the submarine as a threat. These vessels not only escorted transports carrying war materials, but even carried war material themselves. According to various international protocols established to govern such actions, AMCs were required to fly the flag of their nationality at all times; using the flag of a neutral was considered a form of illegal subterfuge.

International protocols did allow for neutrals and civilian vessels to carry some war materials to belligerent nations, particularly small arms ammunition which was considered insufficient to wage offensive war. Nevertheless, there is plenty of evidence that British civilian vessels carried munitions that were illegal according to these protocols. Typically, the passengers sailing on these ships had no knowledge of the deadly nature of the cargo carried below deck. To compound matters, there are known instances when British merchant vessels hoisted the United States flag when in the dangerous waters around Great Britain, thereby trying to deceive German submarines that may be lurking nearby that they were a vessel from a neutral country. Edward M. House, a special advisor of President Woodrow Wilson, witnessed such an incident in January 1915 while sailing to Britain on the Lusitania. As the United States was neutral at the time, House was quite troubled by the implications of such a ruse, though the distinctive silhouette of the ship would have given it away regardless.

Whether or not the second explosion was caused by munitions, coal dust in an empty bunker or a ruptured boiler near the bow is immaterial. What is important is that the Lusitania was sailing passengers, many from neutral nations, into a war zone where similar vessels were running as AMCs, thus blurring the lines between combatants and non-combatants. As can be ascertained, this is not dissimilar to the dilemmas faced by some today as they travel through areas racked by civil war and foreign invasion. The loss of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 over Ukraine, where none of the passengers aboard were Russian or Ukrainian, underscores this danger. The airspace over the area of Ukraine in question was frequented by military aircraft on combat missions making an accidental shoot-down more probable. Yet, if history is a reasonable guide then such a tragic loss should have been expected.

The sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 highlights the dangers that noncombatants face when entering war zones. It also accentuates the precarious diplomatic problems nations face when their citizens choose to transit such areas, even after being warned. After all, the German embassy in the United States had placed notices in newspapers warning people of the dangers of entering the war zone around Great Britain prior to the Lusitania's sinking. Nations, either feeling it necessary to protect their own in extreme situations or even looking for excuses for a war, could find themselves pushed over the edge into a conflict far beyond anything they had envisioned. Once the United States entered World War I in 1917, the worst of the killing was over. The nations of Europe had already been thrust headlong into a disaster by small incremental steps that culminated in more than 10 million dead. It is hard to believe that anyone, even the most militaristic leaders in Europe, envisioned such a catastrophe when they made the choices they did in the summer of 1914.

While the Lusitania is one of the better known ships to be lost at sea, it did not have the greatest loss of life. That dubious distinction goes to the German luxury liner Wilhelm Gustloff, sunk off the coast of Pomerania in the Baltic Sea on 30 January 1945 while attempting to evacuate thousands of refugees and wounded Soldiers ahead of the Soviet Army's advance into Germany during the closing days of World War II. Over 9,300 died in this single tragedy.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

For further reading...

Dead Wake, by Erik Larson

The Lusitania Story, by Mitch Peeke, Kevin Walsh-Johnson and Steve Jones

Exploring the Lusitania, by Robert Ballard with Spencer Dunmore

Social Sharing