FORT BLISS, Texas - The men and women who served their country during the 'war to end all wars' are generally revered and commonly romanticized in films. For many of these individuals, however, their experience didn't define them so much as add to their wealth of knowledge and understanding; they see the war as a task simply needing to be done.

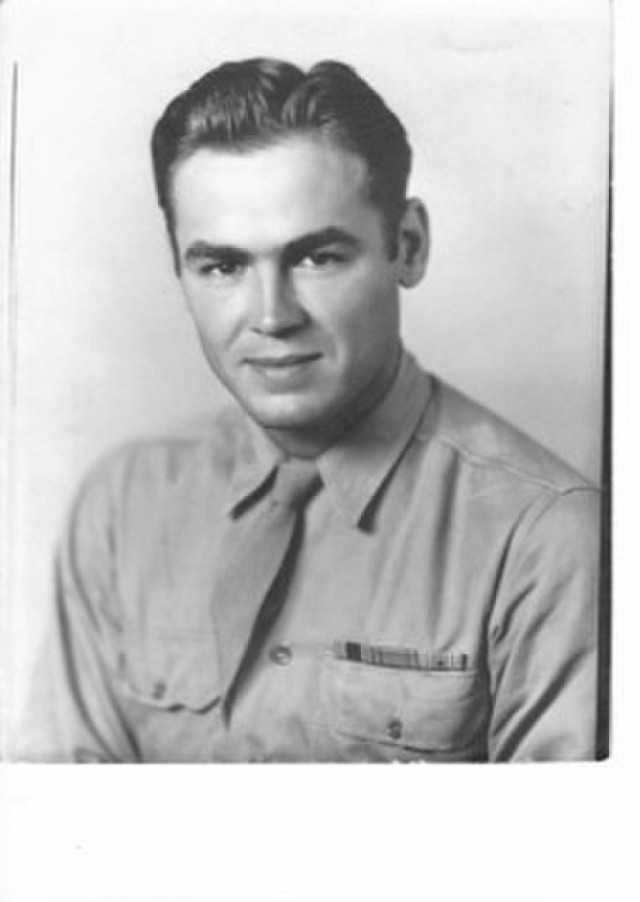

Harry Brodie is one such person; his service during WWII is purely a footnote to his long list of experiences. When asked about the war, he'll respond with an air of playful reluctance, saying, 'I don't want to talk about the war, I didn't really do anything.' With a bit of probing though, an admirable story unfolds.

Born in Kenosha, Wis., in 1919, Brodie knew tragedy early in life: his mother died when he was just eight years old. He then came to know separation when his father, being overwhelmed with caring for four sons in the wake of the Great Depression, sent him and his brothers to live with relatives and church members.

At the age of 11, Brodie and his brothers found a home where they could all be together at the Allendale School for Boys in Allendale, Ill., an orphanage still in operation today.

"We had a really good time," said Brodie. "It was run by a really nice German couple who always took care of us. It was the first time I felt secure. We would have chores, like tending the farm, and there was a lake where we could go fishing. It was a real family-like atmosphere.

"At the end of eighth grade, we were back living with our father in a one room apartment in Chicago. After high school, I got a job making die casts and drilling holes in lamp fixtures. I must have been doing a good job because I was told that they were going to make me a machinist's apprentice."

During this time Brodie made the decision to follow in his brothers' footsteps and sign up for military service. His three older brothers were already in the U.S. Navy, yet he decided to join the U.S. Army.

"They said I could volunteer for one year, do my time and I could go back to my job," added Brodie. "That was in 1941, and of course the war had broken out and I ended up staying in."

Brodie's introduction to military service took him to Camp Haan, located in Long Beach, Calif., for basic training, after which he began training as an artilleryman. He was eventually assigned for the re-taking of the Aleutian Islands, a string Alaskan islands extending into the Pacific Ocean.

Notoriously referred to as '19 days in hell,' the battle for the Aleutian Islands was meant to eventually provide a strategic jumping off point for the overall invasion of Japan. These efforts primarily took place at the island of Attu. At the age of 96, many of Brodie's recollections have been lost to time, but he still has several vivid memories.

"It was a hell of a landing," said Brodie. "We were supposed to go on a Tuesday, but the sea was too rough. So the next day, we circled around the island about eight or so times, then we landed - two ships at a time.

"I didn't have any fear of any kind, except when we first landed. That was an awful feeling. They'd drop that ramp down with a bang and you'd just take off. When you're as young as I was then, you didn't think about dying or anything. You just do what you're supposed to do."

Brodie was part of the second wave of troops to land on the island. The previous wave of 500 troops had taken heavy casualties.

"Then we climbed the mountain and down into Holtz Bay, which was on the west side of the island," added Brodie. "They were firing bursting bombs overhead, hoping to get a few of us. We'd duck down and then start moving again. It was hard to tell where they were firing from because they had powderless ammunition.

"And that was about it. By that time, we had killed most of the Japanese. They fought to the last minute; they would even fight you with a stick."

Brodie would end up spending a total of 15 months on the island, performing various tasks such as building up the airfield, maintaining living quarters and artillery training. As is common with military operations, there was an abundance of down-time that provided opportunities for mischief. Brodie recalled some of his more light-hearted activities.

"I remember the craziest things," Brodie said. "In order to clean the soot out of the chimney in our Quonset huts, we'd throw a couple rounds of powder from the guns and then blow it up, and it'd blow a hole in the tent. Another thing we'd do ... when they unloaded the ships, they'd put it on the beach, then we'd sneak down and get the coffee and peaches - the good stuff."

After the war, Brodie was honorably discharged at the rank of corporal in November of 1945.

While raising his family, Brodie was always hesitant to talk about his wartime experiences, yet just knowing he had served was enough to have an impact on how his family perceived the military.

"The thing that I admire most about my father, and in military guys, is the braveness, the 'I've got a job to do and I'm going to do it,' simple as that," said Brodie's daughter Lynette. "I think because he never really talked about it, we never really understood much about it. But as you get older and you start understanding more about war, you start realizing how devastating war is, how hard it is and that young men give their lives. You start wanting to know more and understand what they went through."

Lynette credited her father's strong character and resilience as a result of his life experience, adding it provides a shining example for her and others to emulate.

"Since he was a kid, he's had to deal with so many dramatic things ... he just does it," Lynette said. "He gives me courage and strength that I can get through this life somehow, someway."

Brodie's other daughter, Dee Mathis, recalled small mentions of her father's service from when she was younger. While his Army time may have affected his own tastes, he never let it take any of the fun from their childhood.

"What sticks out in my mind as a child growing up, in reference to my dad's military service, is his feeling about camping out," Mathis said. "He didn't like to go camp out in a tent. He would say he got his fill of that in the military. They would have to camp out for months at a time in the rain and snow, and he got his fill of that. So he would set up a tent for us in the backyard and we had just as much fun."

The hardships Brodie endured throughout his youth resulted in a personal strength that resonated during his military service. The ability to persevere perhaps goes best with his own personal philosophy of living life without regrets.

"They (the Japanese people) no more wanted the war than we did," concluded Brodie. "I'm not sorry about anything that happened to me. We did some crazy things, but I came out alive."

Social Sharing