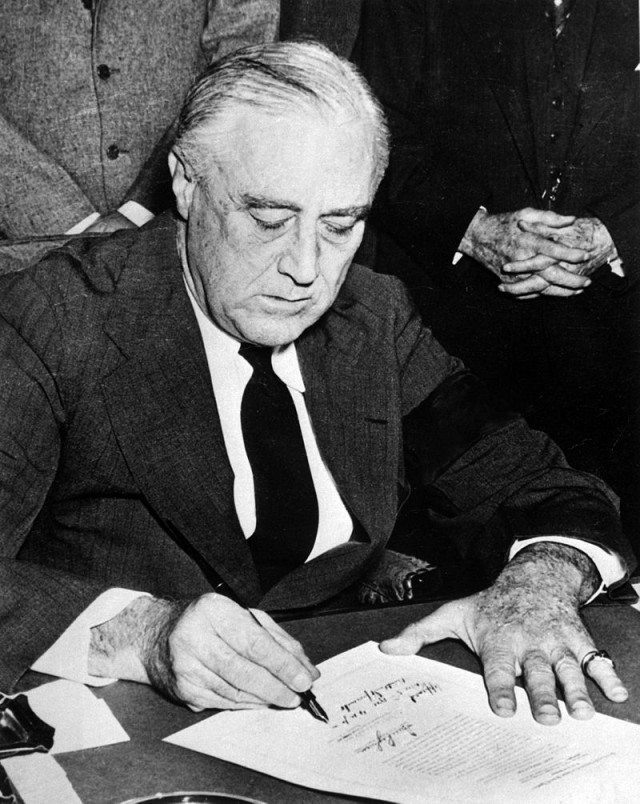

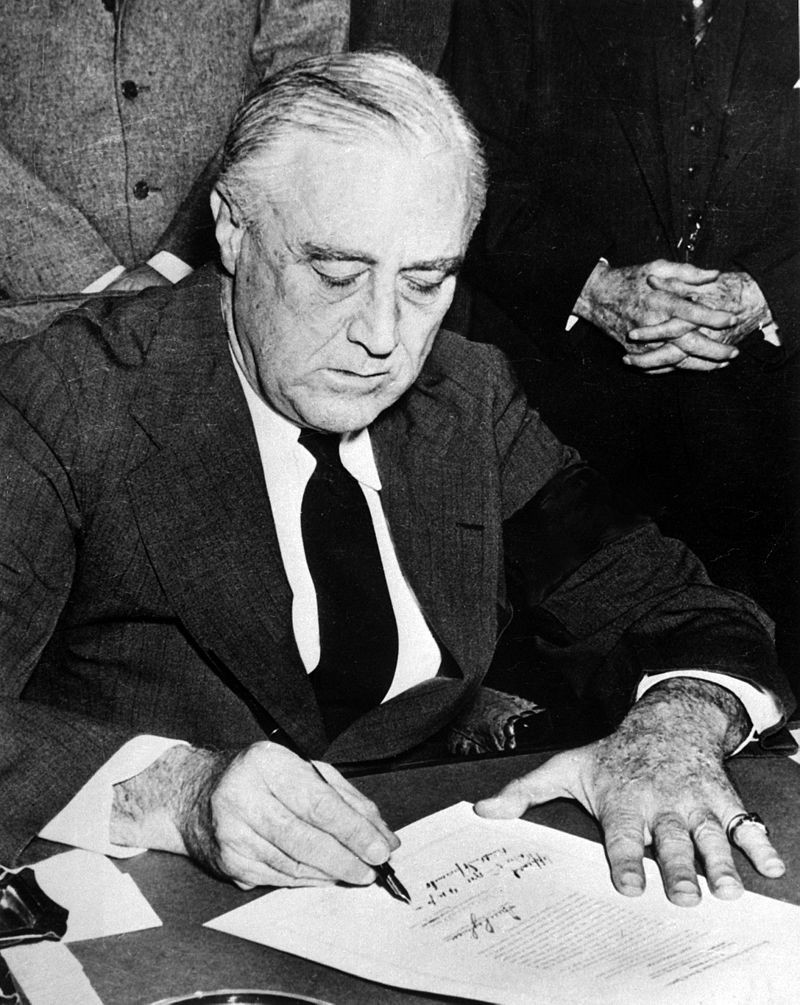

WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Dec. 8, 2014) -- On Dec. 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan carried out a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The next day, President Franklin Roosevelt told a joint session of Congress that Dec. 7 is "a date which will live in infamy." Immediately after, Congress declared war against Japan.

On Dec. 11, Congress declared war on Germany shortly after that country declared war on the U.S.

At the time, the U.S. simply did not have enough forces or equipment to mount a large-scale attack against the Axis Powers. The U.S. Army went into World War II with an end-strength of just 189,000, ranked about seventeenth in effectiveness among the armies of the world, just behind Romania, wrote Cristopher R. Gable in the U.S. Army Center of Military History publication: "The U.S. Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941."

The result of being a hollow force was U.S. forces forward-stationed on Wake Island, Guam, the Philippines and elsewhere would be forced to surrender within days or weeks, because help wasn't coming.

It's a situation with some similarities to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Just a few years earlier, the Army had a significant drawdown of forces. And today, unanticipated global threats to national security are emerging even as the Army is once again in a full-scale drawdown, according to senior Army leaders.

LOUISIANA MANEUVERS

Although the Army was not adequately manned or equipped at the start of World War II, its leaders were not sitting on their hands.

A number of plans were drawn up, the most famous being the Rainbow Plans, said Center of Military History historians. The plans were called that because each color represented a possible adversary. There was even a plan for war with the United Kingdom. Orange was the color representing the plan for war against Japan, but the thinking at the time was that Germany, which was black, would be the likeliest adversary -- although technically black isn't a rainbow color.

Accordingly, the Army prepared for war with Germany by studying its successful blitzkrieg strategy in Europe. Those lessons were applied to the largest exercise ever up to that time, known as the Louisiana Maneuvers.

About 400,000 Soldiers participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers, in 1940 and 1941, testing all their personnel and equipment in maneuver warfare. Even National Guard units joined in. It could be compared today to a large-scale exercise at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California. Wartime leaders, Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lesley J. McNair, Omar Bradley and others all participated as well.

The exercises were especially important, Center of Military History historians said, because Soldiers had never fought large-scale battles using tanks and maneuver warfare. When war was declared, about half of each newly-created Army division was outfitted by Soldiers who had received this type of training. These Soldiers would be expected to train the many raw recruits who would fill out the rest of the ranks.

Inevitably, mistakes were made by Soldiers practicing new maneuver-type tactics and procedures. As a result Gen. George C. Marshall, who was then chief of staff of the Army and would remain so during the entire war, was called to the Capitol to testify. According to Gable, he told a senator in September 1941: "My God, senator, that's the reason I do it. I want the mistake [made] down in Louisiana, not over in Europe. And, the only way to do this thing is to try it out, and if it doesn't work, find out what we need to make it work."

Marshall was also hard on himself and invited criticism from his subordinates. In July 1940, he told Bradley -- who was a lieutenant colonel at the time -- and his fellow officers: "Gentlemen, I am disappointed in all of you. You haven't disagreed with a single thing I've done all week."

Marshall also demanded results,and a certain amount of risk from his subordinates.

On Dec. 14, 1941, Marshall told then-Brig. Gen. Eisenhower: "I must have assistants who will solve their own problems, and tell me later what they have done."

As Soldiers participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers, Soldiers of the Army Air Force were beginning to train in both the traditional support of ground forces and the new concept of strategic bombing, according to Gable.

Eventually, the Army would grow from a mere 189,000 to a peak of 8.3 million.

Decades later, Army Chief of Staff Gordon R. Sullivan would draw inspiration from the Louisiana Maneuvers, even as he presided over an Army that was drawing down in the 1990s, following the end of Operation Desert Storm and the Cold War.

Sullivan prepared the Army for 21st-century warfare, testing new doctrinal and organizational ideas and taking advantage of new technologies -- computers, networks and simulation, to prepare the Army for the next fight, said Retired Brig. Gen. John Brown, the chief of military history at Center of Military History, from 1998 to 2005.

Today, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno is following in those same footsteps, overseeing the Army's operational planning into an uncertain future with multiple threats. He and the Army's Training and Doctrine Command recently released the Army Operating Concept, a document that describes how future Army forces will prevent conflict, shape security environments and win wars, while operating as part of the joint force and working with multiple other partners.

Odierno and other senior leaders have also testified to lawmakers on the impact of the drawdown and sequestration, warning that the Army may not be properly equipped, trained or manned for another Pearl Harbor or 9/11.

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService, or Twitter @ArmyNewsService)

Related Links:

Army.mil: Professional Development

Social Sharing