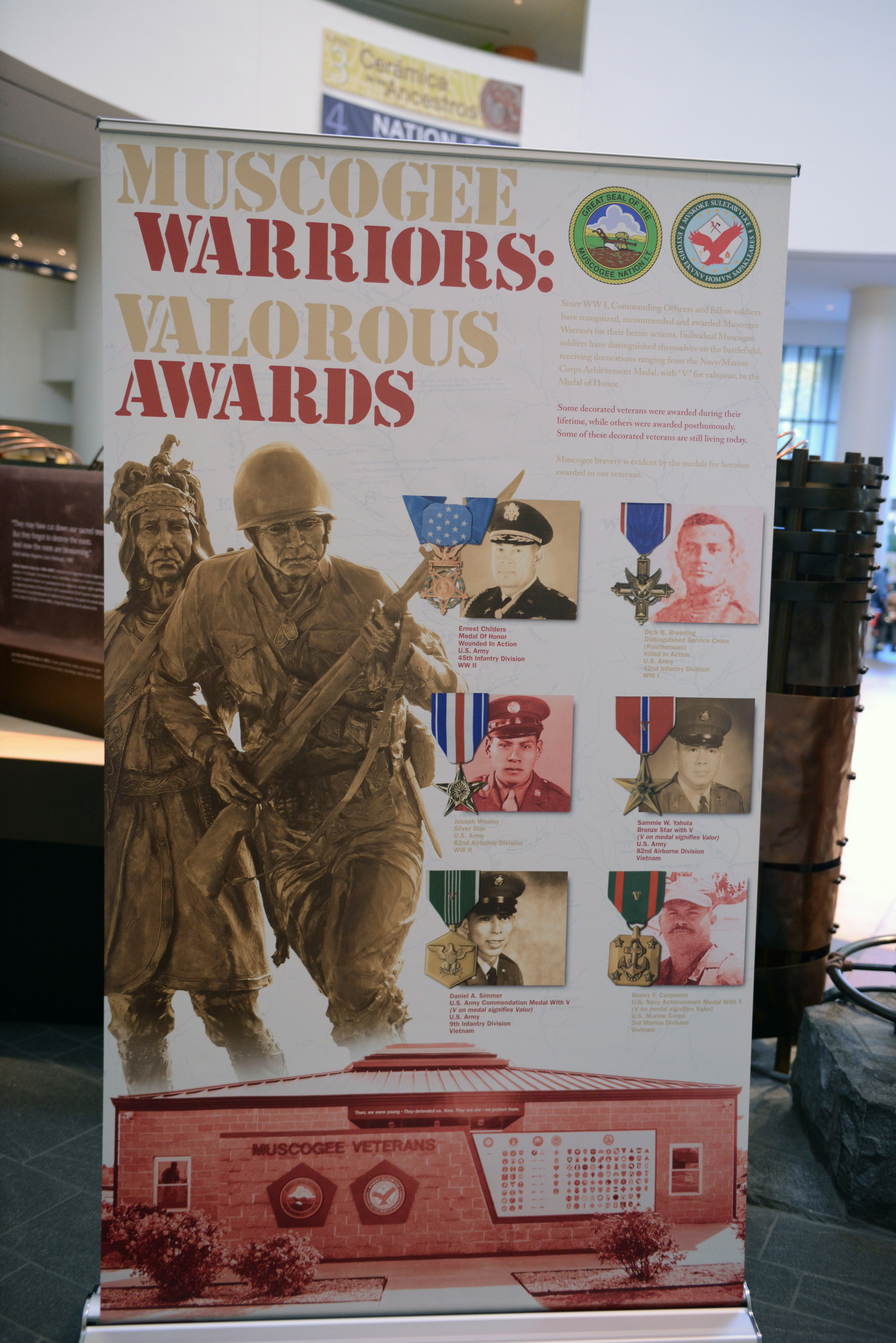

WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Nov. 17, 2014) -- Military service for Muskogee and other Native American tribes is more than just a civic duty, said Harry Beaver. For them, the warrior spirit is a way of life. "Every tribe feels the same way. It's just in them."

Beaver, the youngest of six brothers, would have joined the Army just like the rest of his brothers did. But he was not eligible due to a physical disability, said the Muskogee Native American.

The Creek nation is another name for the Muskogee, who first lived in Georgia and Alabama, but were forcibly removed during the 1830s, to territory that is now Oklahoma.

Two busloads of Muskogee, including Beaver, made the trek from east-central Oklahoma to the Smithsonian American Indian Museum here, where they celebrated the Muscogee Creek Festival, Friday through Sunday. November also marks the celebration of Native American History Month.

The warrior tradition is instilled in every boy from a young age by his parents and grandparents, he said. Stories of bravery and sacrifice are passed along by word of mouth in the oral tradition.

Today, Beaver spends most of his time in Oklahoma scouring lake and river banks for shells, which he takes home and carves. He said he finds most of his shells in the winter when the water level is usually lower and more shells are exposed.

He looks mainly for the thicker shells that won't break as easily when he carves traditional Muskogee scenes such as animals, festivals and warrior themes. Shell carving has been a Muskogee tradition long before Columbus's so-called discovery of America, he said.

Archaeologists have combed through shell mounds in Georgia, where they've come across ancient Muskogee carvings. Beaver said he carves scenes from pictures in books that archaeologists have published, keeping the tradition alive.

Another Muskogee Indian at the festival who is keeping his tribe's tradition alive was Jimmy A. Deere, the last known ballstick maker who uses traditional, non-electric tools.

Ballstick, also called curved stick, looks similar to the stick used in lacrosse, another Native American game. But the stick is different and the game is different, Deere said, adding that his tribe played ballstick long before the arrival of the Europeans in America.

Instead of one stick, each player uses two sticks made of hickory to catch the ball in a clasping motion, he said. Although players cannot touch the ball, they can get tackled by opposing players, so in that regard it resembles football somewhat. First aid stations are set up on the sidelines, as the game can get pretty rough.

Deere said he learned to make ballsticks as a youngster from a medicine man.

When Deere was 5 years old, his father died. His brother, Charles Kenneth Deere, born in 1947, a year earlier than Jimmy, then became a father figure to him, he said. Since they were so close in age, they "played and fought, but I also looked to him for guidance."

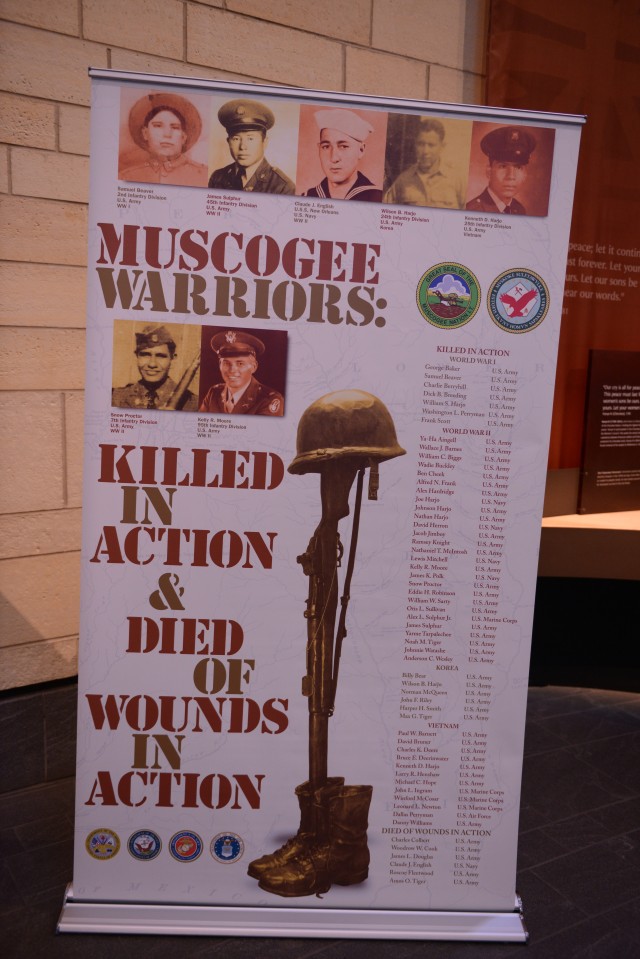

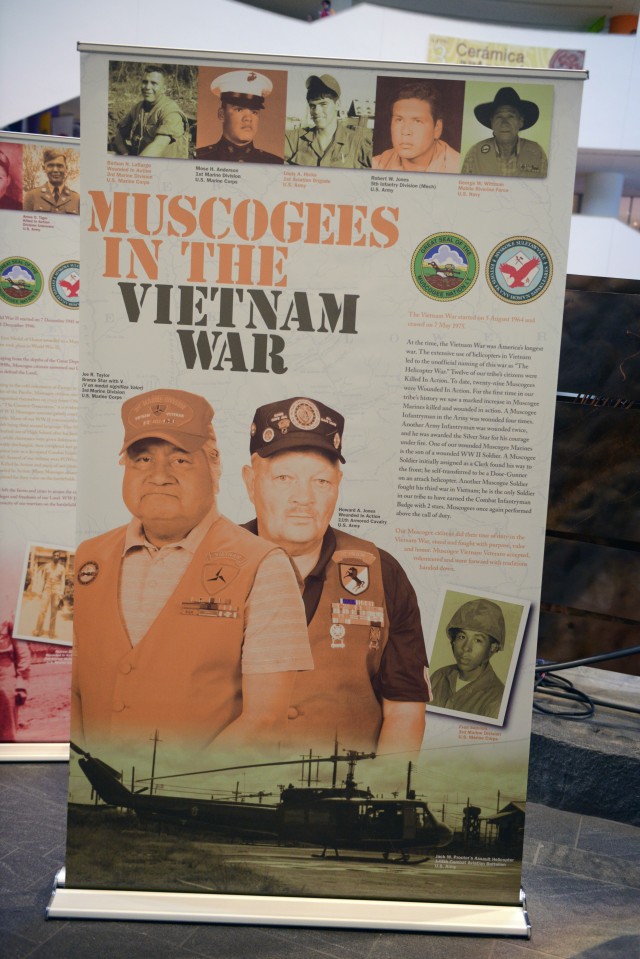

Charles later joined the Army and went to Vietnam as an infantryman with the 101st Airborne Division. The private first class was killed by enemy fire in Binh Duong, South Vietnam in 1968, along with dozens of his comrades.

Deere said he still feels a deep sense of loss and sorrow today, and sometimes visits his brother's gravesite at a church cemetery near where they grew up in Oklahoma.

A cousin who was just one day older than Deere also was killed in Vietnam, he said.

The warrior spirit of the Muskogee and other tribes lives on in military service today, but with it come sacrifices and at times, great sorrow, he said.

Muskogee in Oklahoma live on tribal land -- not reservations -- shared with non-Native Americans. Children and even teachers in public schools sometimes don't understand Native American culture and discriminate, he said.

It is still a strong tradition among Muskogee to teach children their native language and customs first and English as a second language "so the language and traditions don't get lost," he said.

When his son was in pre-school, he was sent home with a note saying the child was "dysfunctional and talking gibberish," Deere said, noting that he and his wife had to explain that the child was speaking Muskogee and was still learning English.

Deere said he's proud of the contributions his tribe has made to the United States and he's confident that the warrior traditions, language and culture will continue to be passed down for many generations to come.

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService, or Twitter @ArmyNewsService)

Social Sharing