(Editor's note: This story about a 10th Mountain Division (LI) Soldier who was forced to train as a child soldier while growing up in South Sudan ran as a three-part series in the Fort Drum Mountaineer throughout the month of July 2014.)

BAGRAM AIRFIELD, Afghanistan -- Pfc. Anthony Lodiong serves as a U.S. Army logistician with 10th Sustainment Brigade, currently deployed to Bagram Airfield in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. He spends his days working at the brigade's humanitarian relief yard, but he is haunted by early memories -- memories of war and of a stolen childhood.

In 1992, Lodiong lived with his family in Kaya, South Sudan, a small town that borders the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. He was only 9 years old then, but he vividly remembers the rebel soldiers pounding on his family's door in the middle of a hot summer night. The rebel soldiers barged in and started searching the house.

As he heard the voices and footsteps going from room to room, fear and anxiety forced him to crawl under his bed, but he was found and forcibly taken from his house. The last memory he had before being removed by the rebel soldiers was his mother hysterically pleading with them not to take him.

"In 1992, I got recruited," Lodiong said. "Forceful recruitment is something that is so sudden. You are sleeping at night, and then the soldiers come to your house. They open the door and search the house for you. When they find you, they take you even if you have already served in the SPLA. They gathered us in a nearby field until morning where they identified the former soldiers and sent them to go fight."

The Sudan People's Liberation Army was founded as a guerrilla movement in 1983, organized to fight the Sudanese government. The Second Sudanese Civil War was a conflict, from 1983 to 2005, between the central Sudanese government and the SPLA. The war originated in the southern part of Sudan and eventually spread as far as the Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains.

Over the course of the war, approximately 4 million people living in southern Sudan were displaced at least once, some multiple times. Originally from Kajo Keji, Lodiong's family was forced to leave to avoid the fighting that had erupted. They moved to Yei, which is some 80 miles west, where his father worked for the U.N. as a camp commander helping Ugandan refugees.

Yei is where Lodiong was born and lived for a year before his family decided to move back to Kajo Keji in 1985. Because of the fighting, they had to keep relocating to try to stay away from it. His family moved all over southern Sudan.

Eventually the fighting caught up with Lodiong and his family.

"There is no way to escape," Lodiong said. "They force you to do it. We were all young children from 8-14 years old."

There was an order saying everyone going to primary school must be trained and recruited into the SPLA, he said.

Training camp

He said the camp was on the outskirts of Kaya to make it more difficult to sneak or run away during training.

"The memories of the training I had … wow," Lodiong said. "I still remember my trainer. His voice was so loud. At night, I can still hear him giving us orders for marching and other training."

Lodiong said the training is normally six months long, but his lasted only four months because the SPLA desperately needed more soldiers to go and fight. The conditions were hard, as they were given very little, but the young recruits always tried to do their best during the training. His trainer would tell them they are guerrilla soldiers and had to learn the hard way.

"Some of the other training camps had some really serious training and some people even died during the training," Lodiong said. "I was happy during my training because nobody died. We were all child soldiers, so the conditions were not as tough as the older group's training."

He figured they didn't want to discourage the young recruits.

"When I was growing up, I had no idea what the SPLA was really about," Lodiong said. "I only knew that it was an organization that had to fight. At that time, I didn't know the reason to fight, but I was ready to fight since I was recruited."

The recruits were housed in abandoned school structures, which are large huts with grass roofs.

Their living conditions weren't much better than their diet, which consisted of beans, hard corn and sorghum, a cereal grass that has corn-like leaves and a tall stem bearing a cluster of grain.

"That is your lunch and dinner every day; there was no change of diet at all," he recalled.

The child soldiers each carried a wooden rifle every day during training, as their trainers wanted them to get used to a real AK-47. Training was focused on marching, shooting, attack tactics and group movements. Lodiong can still remember the tactics he was taught to attack the enemy.

He said they only went to the firing range once because they didn't want to waste ammunition. It didn't matter if you were accurate with the weapon. You were considered trained as long as you could point it in the direction of the enemy and pull the trigger.

"I was being trained as the leader of a nine-man group," Lodiong said. "I think it would be compared to a squad leader in the U.S. Army. I was trained on how to lead soldiers in attacks."

After his training, Lodiong returned to his family.

"My parents realized since I was already trained, it was only a matter of time before I was sent to fight in the war," he said.

Liberation

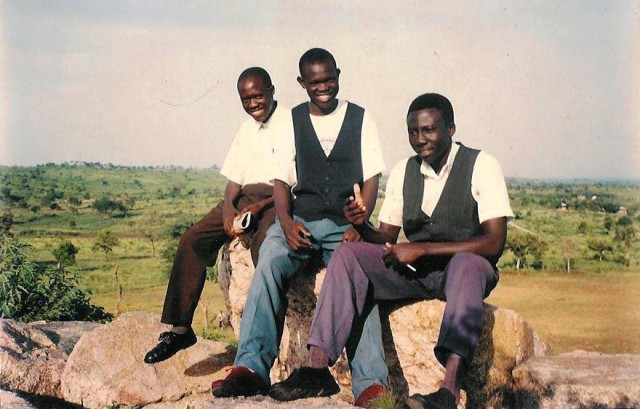

In January 1993, Lodiong's parents snuck him out of the country to Uganda, where he stayed in exile. He lived with his uncle at the U.N. Magburu refugee settlement.

"Living there wasn't too hard," Lodiong said. "That was where I got my college scholarship."

He said if you went to school, studied hard and passed with good grades, you could get a scholarship.

"Looking back, I am happy that I didn't have to go and fight in the war, because I later found out that most of the people I was recruited with and trained with lost their lives," Lodiong said. "There were only a few who survived."

Refugee

Hearing the words "refugee camp," some people might picture a large plot of land with tents pitched and starving people waiting for their next meal.

This, however, was not the case for Pfc. Anthony Lodiong, a U.S. Army logistician serving in Afghanistan with the 10th Sustainment Brigade, who might have even pictured that himself while he was traveling from South Sudan to Uganda. He went into exile in 1993 in an effort to avoid being forced to fight for the Sudan People's Liberation Army at the age of 9.

When Lodiong went into exile, he lived with his uncle at the U.N. Magburu refugee settlement, where he went to school and church and worked on the farm that provided food for his family.

He said conditions in Uganda were not as hard as they were back in Sudan.

"It was different because it was peaceful -- you do not live with anxiety or fear that someone is coming to take you away at night," Lodiong said. "There was no more fear for the Antonov that normally comes. When you (heard) the sound, you ran into a pit or bunker, hoping that the bomb doesn't fall close to you. It was easier to concentrate in school with no fear of being separated from your family if an attack (occurred)."

He said the Antonov is a war plane that the Sudan government normally sent to bomb cities that have been taken over by the SPLA.

"I did not really miss South Sudan so much because my own understanding was that it is a dangerous place to live in," Lodiong said.

Some families had multiple huts, depending on the number of family members. Lodiong would sleep in the hut his family used as a kitchen.

"For other people, there could be up to 10 people sleeping in one room," he said. "I was lucky because I was the only boy at my uncle's house. I was happy because I got my own room. Even if it was the kitchen, at least it was my own room."

Even after Lodiong fled, Sudan was still at war with itself.

"At the end of 1994, the war got serious in South Sudan all the way down to Kaya," he said. "My mother ended up making her way to Uganda, but my uncle decided that since I had already been living with him that I should stay with him."

Lodiong's mother went to a refugee camp about 50 miles away from the settlement.

He said he didn't mind staying with his uncle because he was already settled into his new school.

"Every once in a while I was able to go visit and check up on her," he said.

School

Lodiong finished most of nursery while growing up in Sudan and went right into primary school, which is similar to elementary and middle school.

"As long as I was going to school, I never cared about anything else," he said.

Getting to school was not as easy as going to the bus stop and riding a bus to school like students might do in the U.S.

He had to wake up at 5 a.m. and walk four miles to school. After school, he would walk back to the refugee settlement.

Lodiong said he was lucky because the school he attended was made of bricks and had a sheet metal roof.

"The other schools were made of grass, and the students sat on logs," he said. "I was happy because I didn't have to go to a school like that. I went to a school like that back in Sudan when I was in nursery."

Lodiong said he never had any problems when it came to school work.

"During class I was very attentive and serious," he said. "I had to make sure I understood what was being taught. I would sometimes even ask for books to take home to read."

He said the most challenging part was getting up early every day and making the trek to and from school.

In 1997, he moved in with his mom. That is where he finished his last class of primary school.

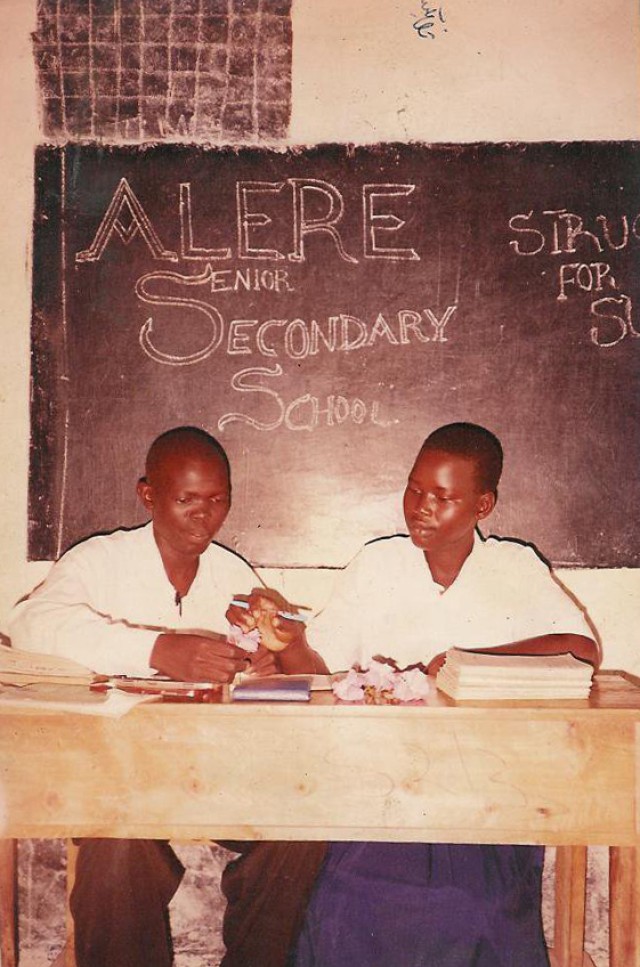

Lodiong did so well in primary school that he received a full scholarship from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugee for secondary school, which is a four-year-long school that is equivalent to high school. Students didn't normally receive full scholarships due to cost sharing.

He said he was lucky to receive a full scholarship to his secondary school.

"Secondary school is a boarding school," Lodiong said. "By that I mean you go and live there."

Lodiong stayed at the boarding school all four years, only returning to the refugee settlement on holiday breaks. After finishing ordinary secondary school, he went on to advanced secondary school, which was also a boarding school but only two years long.

"The advanced secondary school was in another district," Lodiong said. "That's probably 80 miles away. At that time, there was no public transportation in that area. Most of the students would get a group together, get your case on your head if you don't have a bicycle, and we would walk as a team. You wake up very early in the morning. You get there the following day."

Lodiong said during his second year in advanced secondary school, the public transportation began to get better with buses and motorcycle taxis.

When he finished the advanced secondary school, he received a scholarship from the Hugh Pilkington Charitable Trust.

After Lodiong finished college in September 2006, he decided to teach until he saved enough money to make his way back to South Sudan, since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement had been signed in 2005.

The CPA was a set of agreements culminating in January 2005 that were signed between the Sudan People's Liberation Movement and the government of Sudan. The CPA was meant to end the Second Sudanese Civil War, develop democratic governance countrywide and share oil revenues.

"Following the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, I felt I should go and contribute in rebuilding the nation, though I have always thought that it would never ever be totally peaceful," Lodiong said. "It had to start from scratch. There was a request for people who had gone through school to help with the development."

Lodiong moved back to South Sudan in 2007.

South Sudan

As a child, Lodiong said, the living conditions were better in Uganda than they were in Sudan.

"After going back, life was better for me than when I was in Uganda," he said. "I drove my own car to work. I was able to see most of my relatives that I didn't see in over 14 years."

His true passion wasn't to teach, but to become a journalist.

"The teaching profession that I took in college was not exactly my degree of interest, but the scholarships are based on something that can help out the community after you finish," he said. "My interest at that time was really journalism."

The only media office in South Sudan was the Juba Post, which was in the capital.

Lodiong went to the Juba Post in search of a job and talked to the editor.

"I told him that I was interested in journalism," he said.

The editor asked Lodiong to return the following day to start his two weeks of training before working for the Juba Post writing articles.

Seeking even more training, Lodiong applied for radio journalism training.

"One week later I was told I was successful and I had to get ready to go to Khartoum, Sudan, for the radio journalism training," he said. "I was interested in getting all the necessary skills in what I was trying to practice."

After resigning from his position as a reporter at the Juba Post, Lodiong headed to Khartoum for his training.

"When I returned from the training, I got an ad for the Free Voice Foundation," Lodiong said. "I applied because it was a humanitarian organization that was supported by the Dutch government. They had a project called 'Safe at home in South Sudan.'"

While working for Free Voice, Lodiong was a researcher and journalist who went out to neighboring countries, such as Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda, and talked with refugees about returning to South Sudan since the CPA was signed.

Lodiong's findings and reports were turned into a radio drama, which was a way to inform South Sudanese refugees about the changes that had happened.

He worked for Free Voice for approximately a year before he went to work for Save the Children.

Lodiong said he wanted to do something that made a greater impact, where he could see the improvements to which he contributed.

"In December 2008, I saw the ad identifying that they needed a communications officer," Lodiong said. "I read the job description, and it was exactly what I (had) been doing except it would be mostly in South Sudan, so I applied."

He had an interview in January 2009, and a few days later he was told to report for work in February.

"I liked Save the Children because they provided more training and it was a greater humanitarian project," Lodiong said. "They established schools not made from grass and mud. They also provided scholastic materials like books and pens, as well as clinics in the rural areas so people can receive needed treatment."

Lodiong said that he had an emotional connection with the people he was trying to help, and he recalled a memory that has stuck with him.

"I felt so sad when I saw a mother in Maiwut County, Upper Nile State, (get) a cup of water from the river that was brown water," Lodiong said. "(She) gave it to her child, and then she drank it, too."

In the 10 states that make up South Sudan, Save the Children was working with all of them.

"My duty as a communications officer was go to out to all the areas and ensure they were implementing all of the services provided," he said. "We would also conduct a cash transfer where we would give real money to the people who are in need."

Lodiong's main duty was to fly out at least once a week to rural areas and interview beneficiaries of the services Save the Children provided.

"I would present my finding to the project director, who would in turn apply them to the project proposals, such as funding," he said. "My joy comes when the people in need received (supplies) after I present reports to the director and projects are approved and funded."

Lodiong worked with Save the Children until March 2011, when he decided to move to the U.S.

Born during war

Every person who chooses to serve in the military has a story and reason for joining. Some may join for the benefits, some for the chance to see the world, while others enlist for the college money. For Pfc. Anthony Lodiong, a U.S. Army logistician serving in Afghanistan with 10th Sustainment Brigade, these ideas never crossed his mind.

His story is unique. He has gone from a child soldier in the Sudan People's Liberation Army, to a knowledge-hungry refugee in Uganda, to a journalist for the Juba Post in South Sudan and then working with humanitarian organizations before making his way to the U.S. and becoming a Soldier in the Army.

Lodiong said he knew it was just a matter of time before he would leave South Sudan.

"I was born during the wartime," he said. "I had in my mind that this country is not the best place for me to live."

That time came in 2011, when Lodiong decided to resign from his position as a communications officer with the humanitarian organization, Save the Children, and leave South Sudan.

It was time for Lodiong to go and experience life somewhere else.

He had to decide where he was going to start his new life. Australia and the U.S. were two places he considered at the time.

Lodiong had an uncle who lived in Australia who wanted him to move there, but on the other hand, his girlfriend, whom he met while she was working in South Sudan, resided in the U.S.

He eventually decided to move to the U.S.

"I decided to go to the U.S. because it has helped South Sudan become independent, and Australia hasn't done anything to bring peace to South Sudan," Lodiong said.

He went to the U.S. embassy in Cairo to begin the process of moving.

"When I got to the U.S., I decided since I am now in this country, I am a part of this country," Lodiong said. "I love this country, and I need to do something great for this country."

New beginning

He said life in the U.S. is far better than it was in South Sudan.

The weather wasn't the only lifestyle improvement; security and safety were among some of the first things Lodiong noticed.

"In South Sudan, there is no night where you can sleep peacefully not thinking about what might happen that night," he said.

Lodiong said there are no good schools or health care services in South Sudan, and even the roads are bad.

"You drive through the mud," he said. "There are only a few good roads."

Along with the poor road conditions, the economy is in poor shape.

"Food production is a big problem, since the country just got out of war, so everything is imported from other countries to sustain life in South Sudan," Lodiong said. "It is harder living in South Sudan than in other countries."

South Sudan is among the poorest of third-world countries.

"It's very difficult to compare it to the U.S. because (the U.S.) is a developed country and life is generally good," he said. "You have good health care system and a good education system."

Lodiong said Americans are lucky to have student loans and financial assistance.

"Where I come from, you have to struggle on your own or receive a scholarship from some humanitarian organization," he said.

Louisiana seemed like a good fit for Lodiong to start his new life.

"When I moved to the states, I went to New Orleans, because the weather there is comparable to the weather in east Africa," he said.

"I settled there and married my girlfriend," he said. "She was from the U.S. and was already here."

After they got married, Lodiong started doing volunteer work with a hospice company while he was trying to figure out what he was going to do.

"I sat down and thought what I could do to show how grateful I am to the U.S. government for everything they have done for the country where I was before," he said.

U.S. Army

Lodiong came to the conclusion that he should serve his new country by enlisting in the Army.

"That is the only way I can serve the whole country," he said.

He chose the Army because where he came from, there was no other military branch.

"I was forced to join the army (in the past), but that was against my will," Lodiong said. "I wanted to join the Army out of my own free will and see what that felt like."

Lodiong left his home in New Orleans for basic combat training Jan. 1, 2013.

His first duty station was Fort Drum, and he is currently deployed to Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

"I am very grateful that I was able to find the Army," he said.

Earlier this year, Lodiong competed in and won the 10th Special Troop Battalion Soldier of the Month board.

"Lodiong is an outstanding Soldier who knows what it means to be a member of a team," said Staff Sgt. Lobsang Salaka, humanitarian relief yard noncommissioned officer in charge assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 10th STB. "He continues to put the mission first in everything he does."

"Due to his outstanding performance and potential, I have recommended him for the 1st Theater Sustainment Command Soldier of the Quarter board," Salaka added.

Lodiong said he loves how the Army helps him stay in a good physical condition. His most recent goal was to max his Army Physical Fitness Test.

"If other people can do it, then I can do it," he said. "And I did it."

Lodiong took an APFT and earned a score of more than 300. The next day, he participated in a Boston Marathon satellite run at Bagram Airfield, and he was the first person from the Muleskinner Brigade to cross the finish line with a time of 3 hours, 17 minutes.

He said he enjoys running, and he has completed many 5- and 10-kilometer runs.

Lodiong said he finds that in the Army, everything is laid out systematically and there are regulations to follow, and as long as they are followed, problems can be avoided.

He is aware of his responsibilities and always places duty first.

"I work at the humanitarian relief yard," he said. "My mission is humanitarian relief."

The HR mission responds to natural disasters, such as earthquakes and floods, as well as displaced indigenous populace due to insurgent or drug warlord activities, which may assist ground commanders with their counter-insurgency operations.

Lodiong said he enjoys his work at the humanitarian relief yard.

"I'm always happy to see people progress and am willing to help them out whenever I can," he said.

He said he is very grateful to all of the leaders in his chain of command for supporting him and helping him become the Soldier that he is today.

"I am very proud to help the people out who need humanitarian relief," Lodiong said. "It's the right place for me to be."

Social Sharing