ARLINGTON, Va. (Army News Service, May 21, 2014) -- "I truly understand we want the pointy end of the spear and a lot of trigger pullers… But just saying 'reduce the tail, reduce the tail'" is a risky proposition.

Lt. Gen. Raymond V. Mason, deputy chief of staff, G-4, was referring to a "tooth-to-tail" ratio with the tail being logistics supporting the infantry.

He delivered his remarks at the Association of the U.S. Army's "Sustaining Force 2025" seminar here, yesterday.

Like many things in life, he said the ratio involves a tradeoff.

"There are a lot of innovative things can be done to reduce the tail, but just cutting it and taking out capability before putting in a mitigation process and solution set just increases risk."

He then made reference to what Army Vice Chief of Staff John F. Campbell spoke to earlier in the morning -- the notion of "just-in-time" business practice used for military applications.

"The closer you get where people are fighting and dying, business practices don't make sense. But there are money people and programmers that want to drive this."

Just in time, for example, is used by retailers who order just enough stock to fill orders or over-the-counter sales. Any more than that would likely be excess inventory with associated high overhead costs.

Business practice for the military, Mason said, would work out to having just enough ammunition to kill the last enemy with the last remaining bullet.

"We don't want the other end of the spectrum, where there's 'just-in-case' logistics, solving everything with mass. We tend to do that. We did that in Desert Storm and the beginning of OIF," he said.

Once again, Mason pointed out the need to find that sweet spot in tradeoffs, citing two examples, the first being "just-in-case" logistics:

"Many ammunition lines in Afghanistan had 10 years capability on the ground because the commanders don't trust us," he said, adding that one reason may be skepticism in the IT system. "If commanders don't see it, they don't trust the system, so they order more and more ammunition."

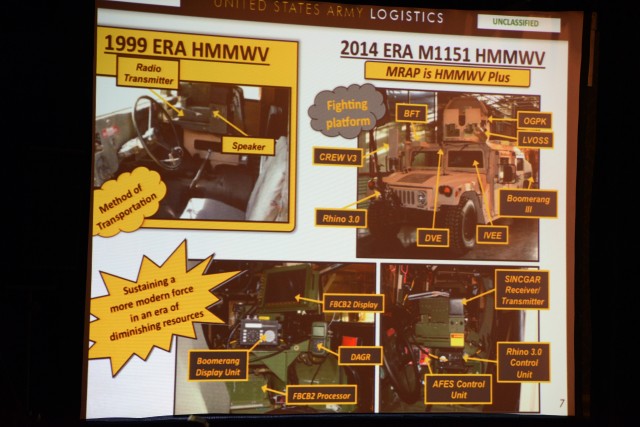

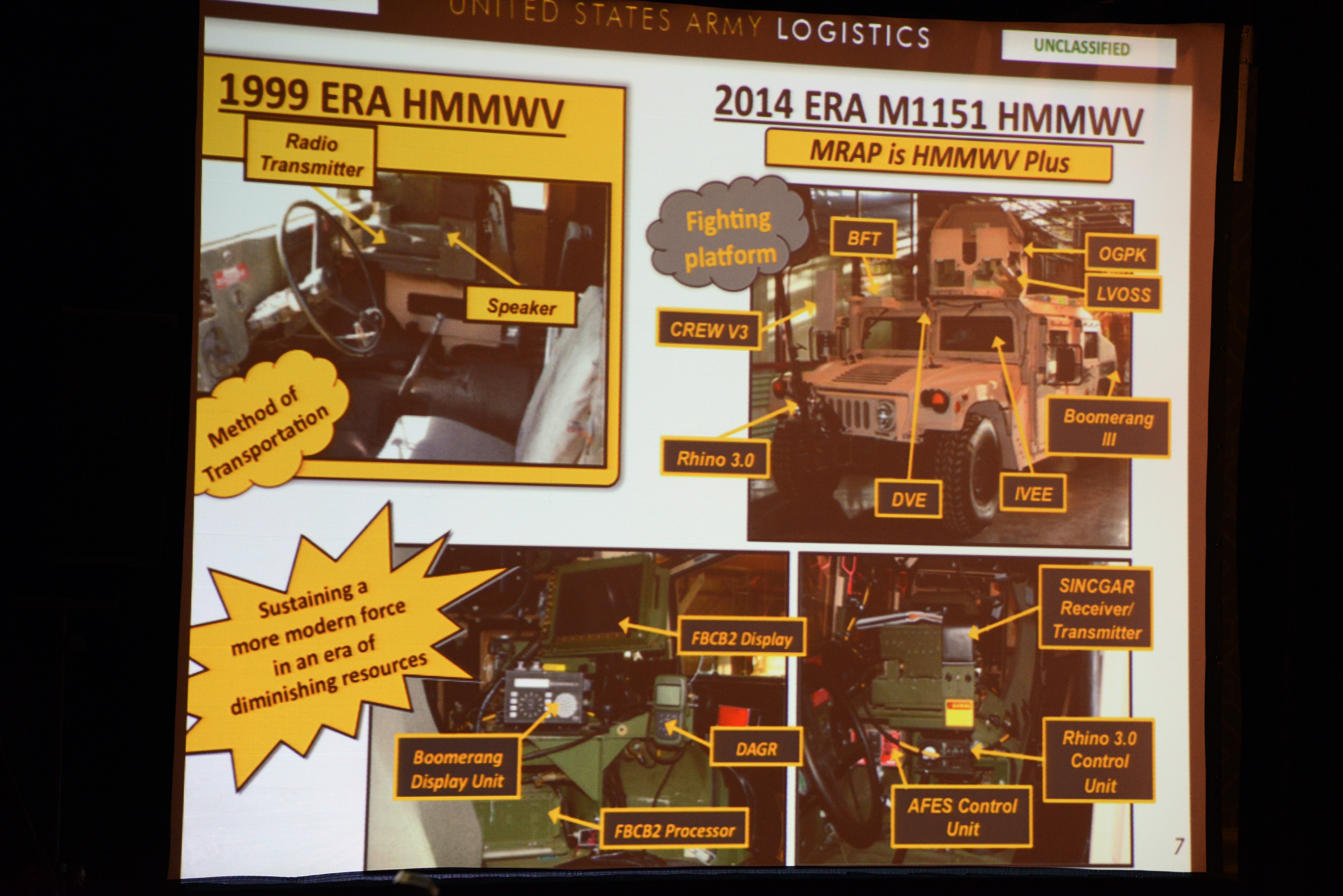

Mason then showed a PowerPoint slide (see attached), showing a 1999 Humvee on the left, and a 2014 one on the right.

The one on the left side looked like a chop shop had cleaned out a lot of goodies while the one on the right was jazzed up for the 21st-century battlefield.

In 1999, "a company commander might have had a speaker and a radio," he said, referring to add-on components. The Humvee on the right was armored and had computerized displays, a gun turret and other gizmos.

Today, "our vehicles have become fighting platforms," he said, just "like Bradleys and tanks."

The Army hasn't really "taken that on," he said, referring to the associated costs from the unit to the depot levels.

The "one on the right is exponentially more expensive at every level of maintenance and repair parts. Do you know what's driving that cost?" he asked the audience.

"Software," replied someone.

"Right," he said. "Software costs are becoming unaffordable. We can't afford to have every vehicle in the Army look like this."

Mason then returned to his tradeoff theme, illustrating how complex a cost-benefit analysis can be.

In the Army's 2025 motor pool, "which vehicles will look like the one on the left and which will look like the one on the right?"

G-3/8 is working their way through that, he said.

"It's a tough thing to do," he explained. "It's a leadership issue as well."

He explained that a corporal who is deployed using the Humvee on the right gets spoiled by the features, and when he "comes back home, they stick him in the vehicle on the left. Then it becomes a motivation and retention issue as well," as a pure cost calculus.

One area that doesn't necessarily involve trade-offs is operational energy, Mason said, referring to it as "a growth industry."

Operational energy involves designing vehicles and generators to use fuel more efficiently and using energy other than fossil fuels when practicable.

"My challenge is to convince leadership to keep investing" in operational energy, he noted.

Besides operational energy, Mason said fuel consumption can also be a leadership issue.

Generators in Afghanistan consume 55 percent of the fuel, powering things like hospitals, living quarters, exchanges, gyms and barber shops.

"FOBs become little Fort Hoods," he said.

Commanders need to ask themselves "how good does it have to be in terms of quality of life?" versus using a lot of that fuel to power vehicles and aircraft.

Mason then illustrated the importance of energy to decision-making by combatant commanders.

There were two metrics Gen. Tommy Franks "had in making the decision to cross the berm" into Iraq, he said. "One was how much fuel we had" and the second was the supply of batteries, which at the time were in short supply.

SACRED COWS

Nothing is too sacred in logistics to question, Mason said, citing four examples:

First, "how does a nation go to war?" and by default, how does the Army go to war?

Ideally, "we're going to go in fast, we're going to go in light, we're going to win, we're going to come home. But when did that happen in our lifetime?" he asked.

In reality, "we go in light and fast and end up staying a long time," he said. Getting out of the fight is more problematic than getting in.

"It's one of the challenges of why people look at the Army and say 'it's so big, it's (deployed) so long, and they can't get out.' That's why they call the Marine Corps."

Not that getting in is a cakewalk either, he said. "We're still in the mode of planning to deploy a year out. That's got to change."

Leadership is aware of that challenge, he said, and is trying to create a more expeditionary Army, with logistics playing a big part of that, which leads to point number two, getting all the stuff over there, wherever there may be.

Most of the heavy stuff is still going to be sea-lifted for the foreseeable future. How that's done may need to change, he said, referring not to new high-speed vessels, which are promising, but something even simpler -- loading them.

"We load our ships administratively," he said. "It's efficient for TRANSCOM, but it's not effective" for commanders.

Ships, and even aircraft, have to be combat configured in loading so what comes out are ready-to-fight platforms, he said. For example, a ship loaded with Humvees and nothing else won't do a commander any good if he has to wait for another ship carrying weaponry. "You don't want to try to build all that infrastructure in the battle space."

A third topic that needs to be thoroughly debated is the "operational reserves."

He noted the fine achievements played by the Guard and Reserve in Iraq and Afghanistan, with Soldiers "asked to leave their jobs with little notice, not knowing if their jobs would still be there when they returned."

But, with only "39 days of training a year, you won't get you an operational combat-ready force. It'll generally just get the individual Soldier ready" with stuff like marksmanship and basic military training.

Just 39 days doesn't provide enough time for extensive unit training, Mason said.

"We may need more investment there," he said, as the Army is relying more and more on the Guard and Reserve. "It concerns me."

A fourth area that Mason said needs to be debated is one of the Army's strategic cornerstones of its formations: modularity. "We gave the brigades everything," he said. Gone are the unit allocations of equipment that's "authorized and required."

While not advocating dismemberment of modularity, Mason said it's "an expensive readiness model we can't afford" and there needs to be more activity on how to "balance" that.

BREAKING HABITS

Others have said that the Army is in the process of moving from a counterinsurgency model to one of full-decisive action and unified land operations, but Mason was blunt about re-learning the complete art of warfare.

"We got bad habits" over the last 12 years of war "when we became boxed in" with counterinsurgency. "We became sedentary when a lot of stuff started showing up at the FOBs," he said.

Many Soldiers don't even know what a ROM is anymore, and many that do haven't done one in the last 10 years, he said, noting that ROM means refuel on the move.

Other lost arts include echeloning logistics capabilities and "jumping the BSA," or brigade support area, he said.

When the Iranians "started getting a little froggy" a while back, Soldiers started looking around for their gas masks, Mason said, with some of them remembering that they "left it back in the locker at Fort Hood."

The Army is also learning to become more agile in its global commitments, he said, a concept referred to as "regionally aligned forces." And, one of the biggest regions is the Pacific, an area Soldiers haven't been fighting in since Vietnam, not counting small counterinsurgency operations.

In its "rebalance to Pacific," the Army is now working on how to put the right kinds of capabilities there, he said. "We just don't see a lot of force structure building up initially. We're looking at putting some pre-positioned supplies there like ammunition and logistics nodes. And, we're looking at where we want to put it, Australia, Guam, we'll see where it goes. But we'll continue to do a lot of exercises" with partner nations.

HAPPY OUTCOMES

The Army has done a lot of things right over the years, Mason said, in a closing note of optimism for the Army of 2025.

At the beginning of World War II, when the nation "was on its butt" and Americans feared California would be invaded, the Army did some out-of-the-box thinking. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, B-25s were stripped down to conserve fuel and were sent to bomb mainland Japan in the so-called Doolittle Raid, he said.

"Tactically, the raid was insignificant. It didn't do anything," he said. But, "strategically, it was huge. It sent out the message 'we can reach out and touch you.'"

That kind of bold thinking and action is needed today, he said.

Another success story is the all-volunteer Army, he said.

"Pundits said if the U.S. ever got into a protracted conflict, it would have to go back to the draft," he said. "They've been proven wrong."

But the all-volunteer force comes with a price tag, he added.

"It's a relatively expensive force in terms of compensation, retirement and medical. That's why all the services are trying to figure out how to control escalating costs, just as health-care costs are rising for civilians. There's got to be some give and take in that and they're working their way through that."

Mason then provided two recent examples of success in Iraq and Afghanistan.

One was the up-armoring of about 50,000 vehicles in a combat zone. It "was kind of like a NASCAR pit stop operation," he said. "We pulled the vehicles off the gun line and up-armored them at night. The industrial base did that. There are literally thousands of Americans walking around today alive because of the work done by the American industrial base."

Another success was achieved in Afghanistan after the main supply route in Pakistan was cut. Commercial aircraft and Air Force transports became the Army's "incredible left partners, flying in supplies," he said, noting that it's a good thing the enemy didn't find a way to shoot them down."

He said "someone should write a book about that" effort, comparing it favorably to the Red Ball Express of World War II, where the allies moved quickly inland from the beaches of Normandy toward Germany, relying on an efficient network of express lanes to move supplies to the front lines by trucks.

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit http://www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService)

Related Links:

Contracting panel addresses initiatives, challenges

Vice Chief: Sustainment innovation key to Army of tomorrow

Army.mil: Inside the Army News

Social Sharing