When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, the US Army's intelligence efforts were nearly non-existent. Early attempts to gather important information about foreign armies had resulted in the creation of a Military Information Division in 1885. In 1903, the division was transferred from the Adjutant General's Office to the Office of the Chief of Staff, where it became the Second Division of the General Staff. However, by 1908, the Second Division had been absorbed by the Third (War College) Division, and the Army's intelligence functions had been relegated to a committee. According to the official history of the Military Intelligence Division, written in October 1918, "Personnel and appropriations were limited, the powers of the committee were narrow and its accomplishments, though valuable, were necessarily meager. Such was the situation at the time war was declared."

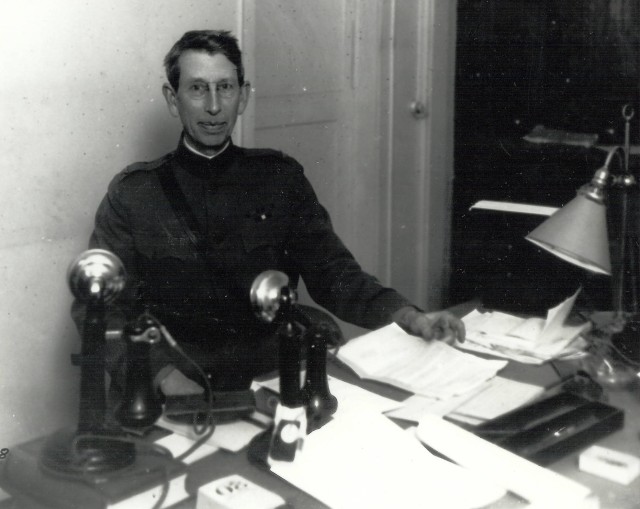

In 1915, Major (later Major General) Ralph Van Deman had been assigned to the War College. Van Deman was a native of Delaware, Ohio, and had attended both law and medical schools before accepting an infantry commission in 1891. Four years later, he was assigned to the mapping section of the Military Information Division. Over the next ten years, he would gain valuable intelligence experience in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and China. Upon his arrival at the War College, Van Deman immediately grasped the implications of the United States' lack of a military intelligence organization. Yet, recognizing this weakness was a minor part of the overall battle to develop a robust intelligence organization for the US Army.

Van Deman wrote numerous memoranda criticizing the ineffectual nature of the War College's committee. He stated, "To call a chair a table does not make it a table--it still remains a chair. And to call the personnel of the War College Division a Military Information Committee does not make it one" [emphasis in original]. His appeals for the creation of a competent organization were essentially ignored. One week after the US declaration of war, Van Deman pled his case in person to Major General Hugh Scott, the Chief of Staff, who refused to consider the establishment of a US military intelligence organization on the grounds that it would only duplicate British and French efforts.

According to Van Deman's memoirs, he found "other means" to reach his goals. While perhaps more anecdotal than factual, Van Deman wrote, "At this particular time one of the best known and respected women novelists of the United States appeared in Washington. She had been engaged for some weeks in visiting various training camps of the Army at the request of the Secretary of War [Newton Baker] and had come to Washington to make a report to him on the matter. Merely by chance, the writer [Van Deman] was detailed to escort this lady to certain of the installations in the immediate vicinity of Washington. In conversations she … was quite audible on the subject of the importance which the Allied military authorities in Europe placed on the work being accomplished by their intelligence services. The writer explained to this lady that there was no military intelligence service in the United States Army and there had not been since 1908. He also explained to her the methods that had been employed to persuade the Chief of Staff to take the matter up and provide an intelligence service and how these methods had failed and that in addition that he had been forbidden to go to the Secretary of War in the matter. She became quite excited and said that she should certainly report this matter to the Secretary of War that very day. Further events revealed that she had done just that."

Van Deman reportedly enlisted similar aid from the Chief of Police of the District of Columbia, a mutual friend of Secretary Baker's. Either because of or coincident to these outside interventions, Van Deman was summoned to Secretary Baker's office on April 30, 1917, to explain the state of US military intelligence. Just three days later, on May 3, the War College received an order to create a intelligence organization and detail an officer to "take up the work of military intelligence for the Army." Van Deman, of course, was the perfect choice to lead the newly established Military Intelligence Section (MIS).

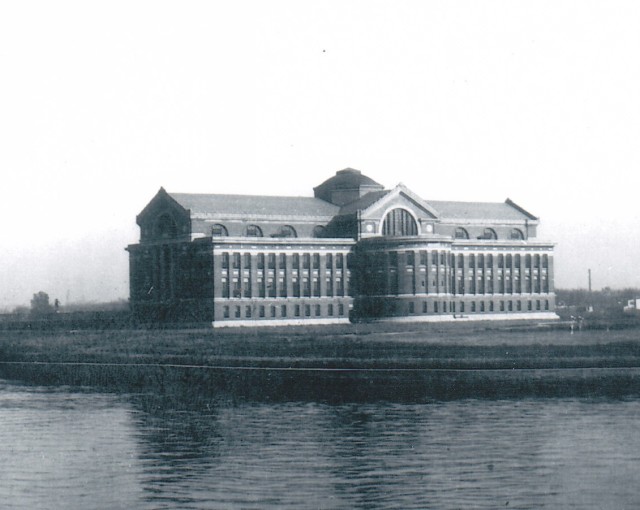

The MIS experienced rapid growth throughout the war. From three main branches in the beginning, by the end of the war, the MIS grew to 12 different functional offices, including those for intelligence collection, espionage and counterespionage, codes and ciphers, attachés, translations, censorship, and graft and fraud. In 1918, the renamed Military Intelligence Division had more than 1,400 personnel, both military and civilian. At this time, it moved out from under the War College to a spot as one of four equal divisions on the War Department's General Staff, a position it has maintained to this day. In addition to equality on the General Staff, other long-standing consequences of the establishment of the MIS were the recognized need for professional intelligence personnel and the preservation of an intelligence effort even in times of peace. That this was a watershed period in US Army intelligence history cannot be understated.

Social Sharing