History provides a wonderful opportunity to learn from the past. It teaches both mistakes to not be repeated and successes to perpetuate.

However, history also provides heritage. As contracting professionals for the U.S. Army, the Army Contracting Command has a legacy that stretches back to the Continental Army and the Yorktown campaign. There have been dark times in our legacy, when budget cuts eliminated skilled contracting officers from the ranks and entrusted the responsibility to the combatant commanders. There have also been bright beacons that show the truly awesome impact of an organized, skilled contracting workforce supporting the Army. In some cases, that work force is the reason for victory. These moments provide more than lessons learned, they provide a legacy of ideals, actions, and results. They provide a legacy of supporting the Army's war fighters above and beyond.

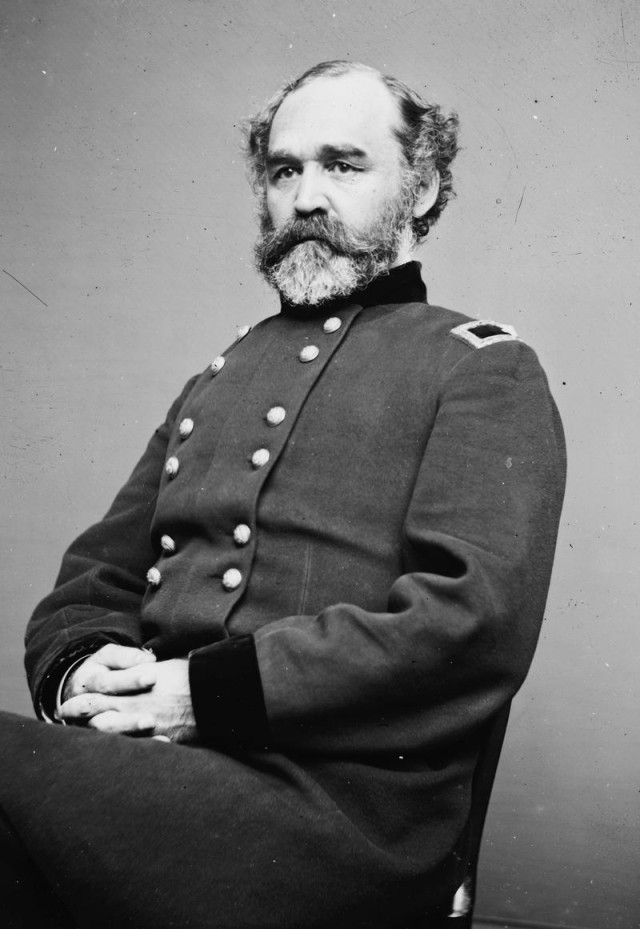

During the Civil War, the U.S. Quartermaster Department held responsibility for all Army contracting except ordnance and medical. Through four years of war the Quartermaster Department obligated more than $15 billion, roughly $279 billion in today's dollars, and accounted for every penny. More importantly, with only two exceptions, the U.S. Soldier did not want for anything during the Civil War; the sieges at Fort Sumter and Chattanooga being the two exceptions. The guiding force of this success was Maj. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs.

According to Robert O'Harrow Jr., Washington Post staff writer, Meigs knew Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was a great leader and his army formidable.

"The rebels are a gallant people and will make a desperate resistance," Meigs wrote to Secretary of State William H. Seward in 1863, "but it is exhaustion of men and money that finally terminates all modern wars."

"The vast, efficient logistical system that Meigs created supported that strategy like no other in history," said O'Harrow.

William Dickinson, co-editor of a collection of essays about Meigs, said that Meigs's appointment as quartermaster general "signaled the beginning of a new style of modern business management in government that would profoundly influence the course of the Civil War."

Meigs and his many assistants, working with private contractors, the nation's railroads, ship builders and others, routinely came up with innovative solutions to the logistical problems the war posed. His men bought or built almost 600 boats and ships. They made, and then laid hundreds of miles of railroad track and ran 50 different rail lines. At the end of the war they owned, and sold, more than 200,000 horses and mules. They built hospitals for the wounded and then buried the dead, O'Harrow explained.

James G. Blaine, former speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives, remarked, "Montgomery C. Meigs, one of the ablest graduates of the U.S. Military Academy, was kept from the command of troops by the inestimably important services he performed as quartermaster general. Perhaps in the military history of the world there never was so large an amount of money disbursed upon the order of a single man…. The aggregate sum could not have been less during the war than fifteen hundred million dollars (sic), accurately vouched and accounted for to the last cent." Seward's estimate was "that without the services of this eminent Soldier the national cause must have been lost or deeply imperiled."

The war would be a long struggle until 1865. But unlike the Confederate Army, which habitually suffered from shortages, the Union Army was generally well clothed and better equipped to endure difficult conditions than their Southern counterparts. The wealth of supply and coordination was attributable to Meigs' unsung administrative genius.

"The corps," he said on that occasion, "has seen great changes since I entered it. It has been expanded till, leavened by the knowledge and spirit and integrity of the small body of officers who composed it early in 1861, it showed itself competent to take care of the supplies and transportation of a great army during four years of most active warfare. It moved vast bodies of Soldiers over long routes; it collected a fleet of over 1,000 sail of transport vessels upon the great rivers and upon the coast; it constructed and equipped a squadron of river iron-clads which bore an important part in the operations in the West and after having proved its practical power and usefulness, was accepted by the Navy to which such vessels properly belonged; it supplied the Army while organizing, and while actively campaigning over long routes of communication by wagon, by rail, by river, and by sea, exposed to hostile attacks and frequently broken up by the enemy; and, having brought to the camps a great army, it, at the close of hostilities, returned to their homes a million and a quarter of men.

"It is now reduced to the proportions of a peace establishment, containing only 64 officers of the staff and about 200 acting assistant quartermasters who hold their commissions in the line.

"During this time the corps has applied to the needs of the Army over $1,956,616,000 and has used this vast sum - nearly two thousand millions - with less loss and waste from accident and from fraud than has ever before attended the expenditure of such a treasure."

"In battle," Meigs reported, "the losses of our equipment have been very large. Knapsacks are piled, blankets, overcoats and outer clothing are thrown off, and whether victorious or defeated, the regiments seem seldom to recover the property thus laid aside."

Such improvidence was disheartening to the Quartermaster Corps, which had such tremendous problems of procurement and distribution. Nevertheless, Meigs tried to be philosophical about it all and, at the same time, to placate Congress, which had to appropriate increasingly large sums of money.

"That an army is wasteful is certain," Meigs reported in 1864, "but it is more wasteful to allow a soldier to sicken and die for want of the blanket or knapsack which he has thoughtlessly thrown away in the heat of the march or the fight than to supply him on the first opportunity with these articles indispensable to health and efficiency."

On November 15, 1864, Sherman began his famous March to the Sea. Meigs, anticipating that when Sherman reached Savannah after living off the land for six weeks or more, having supplies on hand for his army would be necessary and critical, so he ordered a wide range of materiel to be warehoused on Hilton Head Island, just a few miles away but already in Union hands. Waiting for Sherman's men were 30,000 coats and trousers; 60,000 shirts and drawers; 100,000 pairs of shoes and boots; 20,000 caps and blankets; 10,000 greatcoats and waterproof blankets; 10,000 tents, knapsacks and canteens; 100 hospital tents; 5,000 axes (two handles each); 2,000 kettles, pans, spades and picks; and on and on. Sherman's army would want for nothing.

Meigs' quartermaster department instituted the foundation of modern Army contracting; advertisements for bids, contract specifications, quality control, and the depot system all began during this time. Meigs' commitment to the U.S. Soldier, balancing the demands of Congress, the stewardship of the nation's treasury and still ensuring the Soldier wants for nothing - this is the legacy Meigs left for Army contracting professionals.

(Mikhael Weitzel serves as command historian for the U.S. Army Contracting Command and primary historian on U.S. Army contracting history. Weitzel has published several articles and texts for the U.S. Army and continues to research and consolidate Army contracting heritage.)

Social Sharing