During Women's History Month, the Army highlights the contributions of women in its ranks. These women certainly should be commended for choosing to serve their country throughout history in times of peace and war. An often untold story, however, is how the spouses of Soldiers also serve, directly and indirectly. Army spouses regularly raise the children, go to work, and keep up homes by themselves while their Soldier-spouses serve far away in danger zones for months, or often years, at a time. Genevieve Young Hitt was one of these remarkable women. The essence of resilience, she loved her country and was willing to serve just as readily as anyone who has taken the oath to uphold and defend the constitution. Historian Betsy Rohaly Smoot wrote an article for Cryptologia entitled "An Accidental Cryptologist: The Brief Career of Genevieve Young Hitt," which clearly illustrates that women of courage, commitment, and character are not limited to those in uniform.

Genevieve Young Hitt was born into a wealthy society family in San Antonio in 1885. She never attended college, but after completing public school, she attended Mulholland School for Girls, San Antonio's most prestigious finishing school, and later, St. Mary's Hall, a college preparatory school. Here she took courses in history, English language and literature, botany, geology, chemistry, astronomy, mythology, and the history of art, civics, and psychology. Notably missing was mathematics. After graduation, her next eight years were filled with parties, dances, and card games -- all perfectly acceptable pursuits for a young woman with "lady-like deportment, and Christian character," to quote her principal. In short, Genevieve was perfectly trained to marry a man who would take care of her for the rest of her life. Although she had vowed to never marry an Army officer, she met and fell in love with Captain (later Colonel) Parker Hitt, an infantry commander at Fort Sam Houston. They married in 1911 and Genevieve made her first Army move to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas where her husband attended and then instructed at the Army's Signal Corps School.

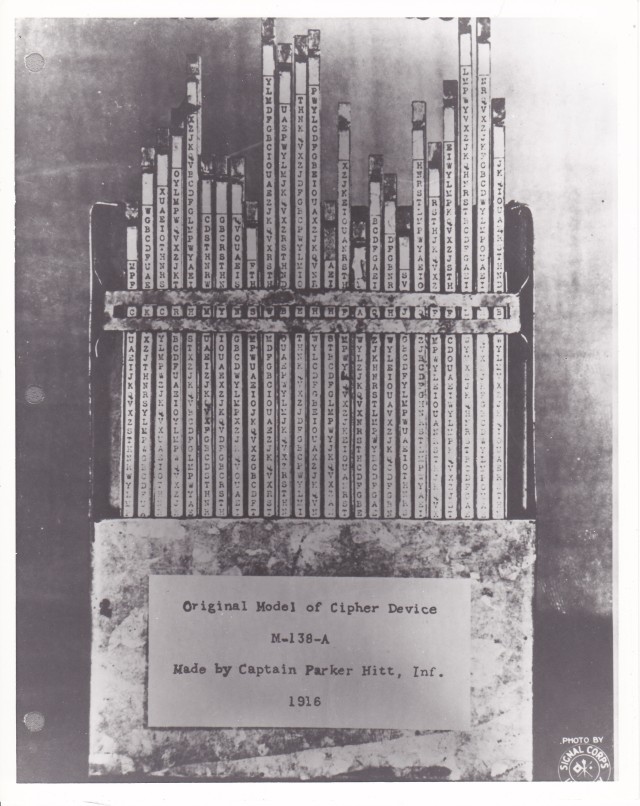

The year of their arrival was coincidental. It was the same year that the Army?'s Signal School began focusing on military cryptanalysis with a series of technical conferences on the topic that captured the attention of Captain Hitt. Historian David Kahn points out in his book, The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing, "[Hitt] discovered that he was 'very much interested in cipher work of all kinds' and that he had a real knack for it." While it is unknown when Mrs. Hitt developed an interest in cryptology, she likely studied the discipline alongside her husband, and became proficient in using the M138-A sliding strip decoding device that Parker first developed in 1914. Genevieve has also been credited with assisting in the preparation and compilation of her husband's seminal work, Manual for the Solution of Military Ciphers, published by the Army in 1916. Obviously, she had a knack for cipher work too.

While Genevieve and her husband were stationed at Fort Sill, Oklahoma the Army put them both to work analyzing intercepted Mexican government messages during the 1916 Punitive Expedition. However, the reality of being an Army wife surfaced when Captain Hitt was sent overseas in May 1917 to serve on General Pershing's staff as assistant to the Chief Signal Officer during World War I. Genevieve moved from Fort Sill to Fort Sam Houston to be near her family. But rather than siting around pining for her deployed husband, Genevieve traveled to Riverbank Laboratories to gain some training in cryptology, meeting another cryptology pioneer, William Friedman. Back home in Texas, Genevieve began receiving hand-written notes marked "For Mrs. Hitt," clipped to cipher messages that had been sent to the Southern Department. Without ceremony or salary, she routinely deciphered them.

In April 1918, the Army finally deemed her work worthy of a paycheck. Genevieve was placed in charge of code work for the Southern Department's Intelligence Officer, Robert L. Barnes, for the salary of $1,000 per year. She worked 5 ½ days per week (plus overtime) coding and decoding official Army intelligence correspondence, maintaining control of the Army codebooks in the department, and breaking intercepted coded and enciphered messages. Except for her brief visit to Riverbank, she was entirely self-taught. Barnes later noted that Genevieve was "specially qualified for such work having made a special study thereof." Her new job was hardly what she imagined her life would be as a young debutante in Texas a few years earlier.

In fact, everything about those times was foreign to Genevieve. On a business trip to Washington, D.C. a few weeks after she began her paid job, she wrote to her mother-in-law about how it was all affecting her:

"All this seems so funny to me, at times I have to laugh. It is all so foreign to my training, to my family's old fashioned notions about what and where a woman's place in this world is, etc., yet none of these things seem to shock the family now. I suppose it is the war. I am afraid I will never be contented to sit down with out something to do, even when this war is over and we are all home again…

This is a man's size job, but I seem to be getting away with it, and I am going to see it through. It does not seem to be affecting my health in any way, for every one says I have never looked so well. I am getting a great deal out of it, discipline, concentration (for it takes concentration, and a lot of it, to do this work, with machines pounding away on every side of you and two or three men talking at once), the other fellow's point of view, and working side by side with the woman who has to work if she is to eat or wear any clothes."

Genevieve Hitt enjoyed the support of a loving husband, which certainly was a factor in her ability to take on such a demanding and non-traditional job. But her work ethic was all her own. In October 1918, she wrote that she had worked six months without a break. Exhausted, she used the work as a distraction against the stress of the war. When it ended, Genevieve resigned, not wanting to stand in the way of other clerks who would need the pay.

Col. Hitt was inducted into the MI Hall of Fame in 1988, and Hitt Hall on Fort Huachuca was named after him in 1995. His wife's service, however temporary and/or voluntary, was also invaluable. Genevieve Young Hitt is an inspiration to all the women who followed in her footsteps in cryptology, an example to Army spouses everywhere, and truly a woman of courage, commitment, and character.

Social Sharing