FORT LEE, Va. (Feb. 27, 2014) -- He donated money to the military services, demonstrating his support for the war effort.

When that fell short of his aspirations, he walked away from a life of privilege, enlisted in the Army and plunged himself into the toil of service, travelling thousands of miles to lift the spirits of fighting men and women.

Ultimately, Joe Louis would have eagerly relinquished his role as morale-booster for the duties of a grunt, gladly shouldering a .50 caliber machine gun on the cold, mud-covered battlefields of Europe, said his son.

"He would have done it," said Joe Louis Barrow Jr. by telephone from his office in Florida. "He would have seen it as his obligation … being the patriot he was."

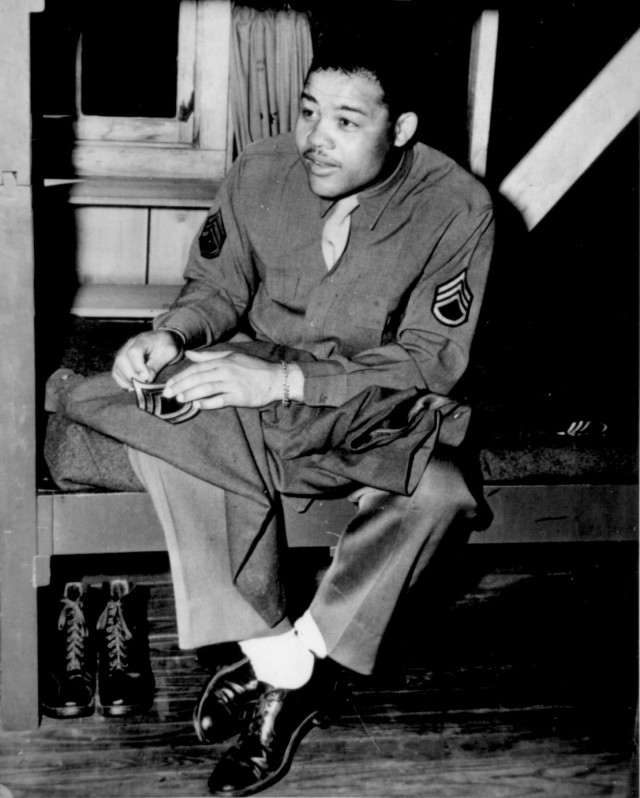

Louis's work as a patriot and Soldier during World War II is a telling tribute to his personal character. He donated the purses from two fights -- nearly $100,000 -- to the Army and Navy relief societies in 1942. When he joined the Army later that year, he would embark upon a schedule of staging 96 boxing exhibitions during nearly four years of service at installations all over the world including Fort Lee on Sept. 15, 1943. More than 2 million military members saw "The Champ" strengthen their sense of purpose through his athletic skills, wholesomeness and humility.

"Everyone relished meeting the heavyweight champion of the world," said Barrow, "and they relished the fact that the heavyweight champion of the world was a Soldier. Whether they were white or whether they were black -- it didn't matter in the sense that he was a Soldier. They knew the indignities that Soldiers had to endure, but he was a Soldier and they loved that."

The champ had cultivated his image after crushing Max Schmeling in 1938 before 70,000 people at New York's Yankee Stadium. Listeners by the millions tuned in to radio broadcasts to hear the man they called the Brown Bomber knock out the German in the first round, retain his title and slap down Aryan idealism in the process. It brought the nation's citizenry together like no other event and was the first time in history that white America had embraced a black man.

"They recognized the fight pitted the freedom of democracy against Nazism," said Barrow of the pre-event sentiment. "He became an American hero because of the situation associated with the fight."

Louis realized after the event the deep impact his fists had on America's collective consciousness. He was the man, the American who single-handedly thwarted, at least superficially, Adolf Hitler's powerful advances and gained a scepter of admiration from the American public. Thus, his newly attained celebrity status presented him with a challenge: as a black man, he was not extended the rights of full citizenship; as champ, he was afforded treatment most black people could never fathom.

Louis seemed to know, however, that his stardom rested on a rickety platform, and he withstood the weight of public adoration with an unwavering sense of humility.

"He knew as an individual not to cross the line," said Barrow. "They would reserve the entire floor of a white hotel, but he'd go to a black hotel. He knew as a black man where his place was. He was under no illusion he was greater than the black race. He felt he was part of the race in that regard."

Although Louis saw himself as a patriot and supported all the troops, he felt a special obligation to support the masses of blacks who had donned uniforms like himself.

"He fought to make it better," said Barrow. "He talked regularly to Truman Gibson (then assistant civilian aide to the Secretary of War) to make it better. He would go on to black bases and see how black troops were taken care of, or not being taken care of, and he would say 'You need to make it right for the black troops down here.'"

During World War II, African-American service members often lived in substandard conditions and received poor training and equipment in comparison to whites.

They also lacked opportunities for advancement. This was especially evident in the Army's officer corps, where a lengthy application process made it even more difficult to join the ranks. When a young draftee named Jackie Robinson applied to attend OCS at Fort Riley, Kan., he turned to the champ for assistance. Robinson became an officer in 1943 with the help of Louis and later broke the color barrier in major league baseball.

Despite his patriotism and support for black troops, Louis was criticized by members of his own community for promoting the recruitment of blacks for an Army that didn't serve their interests and not lending a more vocal presence to the struggle for civil rights. A statement he made in 1943 -- "Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain?'t going to fix them" -- in many ways captured his patriotism but prompted questions about his allegiance to black causes and his willingness to fight for them. Barrow said his father did push for change but did it in a way in which he was comfortable.

"Because he held the title for almost 12 years, people felt he held a status," he said. "Because of that status, people felt he could have an impact. Well, that wasn't Joe Louis. Joe Louis was a mild-mannered, amicable individual who certainly had his beliefs, but chose not to express them openly."

Louis preferred to work behind the scenes when it came to racial issues, according to Gibson in his book, "Knocking Down Barriers: My Fight For Black America." In it, he states Louis endured several bouts of racism in the Army, including one incident in which he and fellow Soldier Sugar Ray Robinson were nearly arrested by military police because they wouldn't change seats at an Alabama bus depot. Louis never made light of the incident publicly.

At the conclusion of his military career in 1945, Louis was awarded the Legion of Merit for his service. In his official military personnel file, it stated he boxed in exhibitions so frequently that he injured himself, putting his livelihood at risk "rather than disappoint soldiers who frantically stormed by thousands to the scene of his exhibitions."

His deeds and actions were not part of a public façade, neither. As a civilian, he continued to navigate his way through the complex maze of race relations as only he could. This was evident in 1952 when he became the first black man to play in a Professional Golf Association-sanctioned event. The PGA was a holdout and staunch-white institution beforehand, but somehow saw fit to include the champ. Louis's breakthrough eventually led to the sport's integration.

Furthermore, he supported the careers of numerous black golfers and played a pivotal role in founding The First Tee, an organization that teaches golf and golf values to youth.

Later in his life, Louis bore the weight of many personal struggles: marital, financial and health problems were among them. The son of former Alabama sharecroppers died of cardiac arrest in 1981. President Ronald Reagan made an exception to policy for Louis's burial at Arlington National Cemetery. Barrow said his father will always be known as the Brown Bomber, but his accomplishments outside the ring deserve recognition in their own right.

"People want to put him as one of the greatest boxers in the world, but they need to understand that his legacy is broader than boxing," he said.

Indeed, the champ was one of the greatest -- beating Schmeling and earning America's respect, losing only three fights in a career that last more than two decades and clutching the heavyweight title for nearly 12 years.

For all of his accomplishments in and outside the ring, however, what was greater than serving his country?

(Editor's note -- Joe Louis Barrow Jr. is the first of Joe Louis's two biological sons; both carry the same name. The source named in this story is now chief executive officer of The First Tee.)

.

Social Sharing