The Army's shift to mission command from the earlier concepts of battle command and command and control has opened up great opportunities for expeditionary logistics. Using mission command, tactical logisticians can leverage leader development and creative training to have a positive effect on strategic landpower.

Army strategic maneuver in the coming years will require junior logisticians, especially those serving in divisional and brigade separate units, to be more flexible and innovative than ever. Familiarity with the regions to which their units are aligned will be as important to company-grade logistics officers as it will be to every other commander.

On the company training calendar, leader development will become as important as military occupational specialty (MOS) task development--to the point that units will be task-organized under the leadership of sergeants and lieutenants in remote locations. How should tactical logistics officers approach the evolving issue of supporting forward units in a strategic landpower-focused Army?

LEADING LOGISTICIANS

For strategic landpower, tailoring logistics to meet the operational needs of supported commanders becomes critical. Just like their combat arms peers, commanders of logistics companies will need to plan and execute realistic training that prepares their subordinate units as part of a ready, relevant strategic landpower force.

Successful commanders will never pass up an opportunity to take their unit to the field and will overcome the urge to support training from the motor pool. They will encourage Soldiers to learn field craft and help their noncommissioned officers (NCOs) establish assembly area operations instead of sleeping in trucks. The conditions in which our units will operate will be austere and demanding, but knowing how to provide logistics support in unimproved locations will bring mission success.

Unfortunately, many leaders at the tactical level of logistics too often view their assets by function, ignoring the human dimension. Logistics units are typically built around groups of similar MOSs, but future commanders should approach complex issues with a flexible and adaptable crew of junior leaders.

The brigade support battalion and the forward support company (FSC) of the armored brigade combat team and infantry brigade combat team are well-suited for linear warfare. But FSCs in particular are not designed to allow platoons or squads to operate independently. Indeed, when short-term mission teams are necessary (for example, during combat recovery missions in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom), they are often ad hoc groups with no formally established "leader-led" relationships.

To support regionally aligned forces' expeditionary maneuver missions, logistics officers at the company and battalion levels should include the human dimension in their training and operational planning. The subordinate leaders' talents will need to be considered along with the tasks necessary to support a strategically expeditionary Army that is flexible enough to achieve our nation's objectives.

Conditions for effective mission command can be set in many ways, and every unique situation will require a unique solution. The following example shows how a 1st Cavalry Division unit developed junior leaders to solve a problem that most likely will reoccur.

THE MISSION

In late 2011, the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division (1-5 Cav), was deployed to northern Iraq in support of Operation New Dawn. As the operation drew to a close, 1-5 Cav was to execute a tactical road march from its forward operating base (FOB) to Camp Buehring, Kuwait, where it would assume the U.S. Forces-Iraq strategic reserve mission. In this role, it was to provide the theater commander with a rapid reaction force to counter violent extremists and insurgents during the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq.

The basic plan was for a rotation of battalions to provide scaled force packages on short notice. These force packages were variable, and the size could be selected by the operational commander based on the threat and location, among other factors.

Units within the on-call battalion that were not part of immediate-response force packages would conduct individual and collective task training. The challenge for tactical-level logisticians was how to provide effective support to numerous dissimilar force packages without encumbering the tactical commander.

At the same time, 1-5 Cav's FSC was conducting its own rigorous training to prepare its Soldiers and leaders to be part of an expeditionary force. The company provided daily support operations to base units and operations.

The FSC was based on a three-platoon layout of maintainers, distributors, and cooks. However, this design did not provide the flexibility and rapid response that was needed for the mission set.

How could the unit continue to provide seamless logistics support, conduct rigorous training, and give the operational commander the tools he needed at the same time? The best solution was the most obvious one: the leaders should task organize the unit and push decision-making power as low as possible.

The task organization plan, compiled by the company leaders in conjunction with the 1-5 Cav logistics officer (S-4), was to build multifunctional teams with clearly defined leadership relationships. Each force package would have its own attached team, which could be quickly augmented to support larger operational forces.

LEADER DEVELOPMENT

The path to successful implementation of the strategy began long before 1-5 Cav deployed in support of Operation New Dawn. When they learned that they would be deploying to Iraq, the S-4 and the FSC's officers and senior NCOs sat down together to determine what the training plan would be. They devised a campaign plan that would be the roadmap.

In this campaign plan, the unit outlined areas where it wanted to excel and areas where it would assume risk. Every leader had input and was given a task. This ensured ownership of the task and achievement of a war-ready standard.

By including NCOs and lieutenants in the campaign plan, the company's leaders hoped to help them see how their roles were critical to success, not just for their platoon but also for the other platoons in the company. In this way, they developed leaders who could train and mentor Soldiers while understanding the battalion's posture and the reason for their missions.

Throughout the year spent training for the deployment, the FSC volunteered for every tactical training scenario available. It executed gunneries, live-fire exercises, expeditionary-style support lanes, and assembly area occupation and activities.

By conducting realistic, strenuous training as a company (when possible), junior Soldiers developed relationships with NCOs outside of their sections. The NCOs could accurately assess the capabilities and weaknesses of individual Soldiers, which is critical to leading teams outside of normal command and control channels.

THE TASK ORGANIZATION PLAN

The task organization plan was tested before 1-5 Cav could even begin the road march to Kuwait. Two days before departure from the FOB, the battalion was tasked to leave behind a security element to ensure the U.S. State Department personnel moving into its footprint had time to properly establish and secure the area. The force package, which would consist of one infantry company with enablers, would remain on the base until further notice. The FOB was hours away from the nearest logistics resupply base and outside the normal radio communications range of any unit.

Since the FSC continued to prepare for the road march south, it did not have time to give detailed orders and plans to the team it was leaving behind to support the security force. This initial trial would be the ultimate test of the mission command strategy. Would the sergeant first class team leader, a food service specialist, be up to the task of leading a team built to serve all company capabilities?

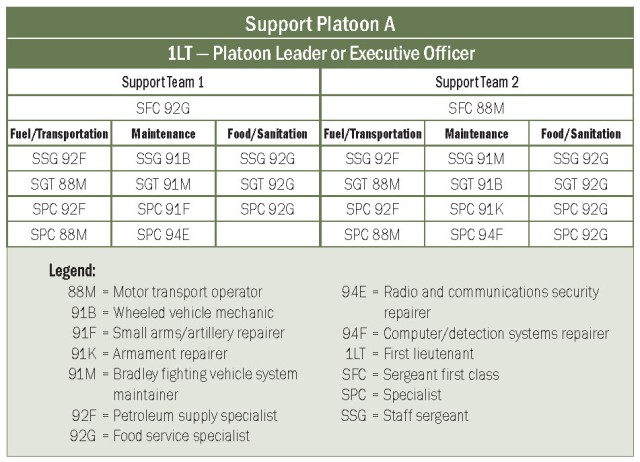

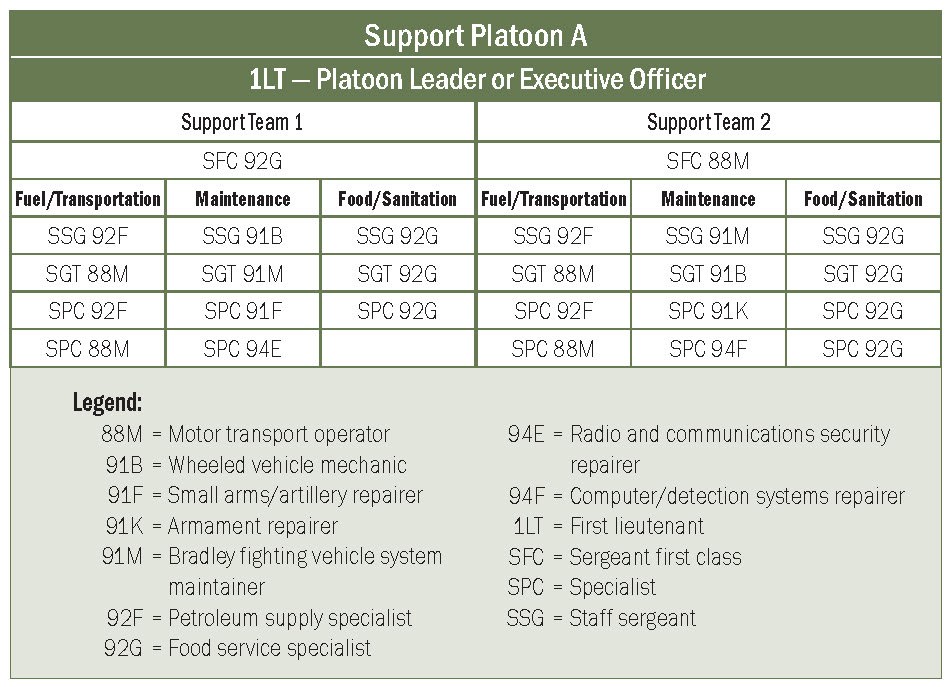

Each team would be made up of 12 to13 Soldiers representing every key function of the company: weapons and electronics maintenance, fuel handling and delivery, field feeding, cargo transportation, tracked and wheeled vehicle maintenance, and combat recovery. (See figure 1.)

The teams would be led by a sergeant first class, and he would have three section chiefs to oversee small teams. These teams would be led by staff sergeants or sergeants, allowing the team chief to embed himself in the supported unit's headquarters.

The ability to gain and maintain awareness--and to be available to the supported unit's leaders--was essential to the success of these team chiefs. By maximizing the abilities of subject-matter-expert junior leaders, the team chief was free to command his element to best support the operational commander. He was unencumbered by minutia, which not only allowed him to oversee the entire team but also made him a valuable subordinate asset to the supported unit's headquarters.

As the FSC had five sergeants first class, one from each of the major functions, the leaders were careful to match personalities, strengths, and weaknesses of team chiefs to subordinate leaders.

For example, the food service section NCO-in-charge was particularly strong in both leadership and technical skills, so he was paired with a less experienced junior NCO to lead the three cooks on his team. The more senior staff sergeants from the field feeding section were paired with other team chiefs to ensure they could provide trustworthy advice to their leader.

The small 13-Soldier team would support the smallest force package, one company--a ratio of one to 12. In the event the second force package, consisting of two companies, was deployed, both support teams would deploy. To ensure unity of command and to better support the operational commanders, this double package would be led by a lieutenant. These roles and relationships were set and rehearsed.

The rest of the company not assigned to a support team was similarly task-organized under the leadership of a fifth sergeant first class. This NCO was responsible for training support for the companies not in ready status, day-to-day support operations at the base, and training for his Soldiers.

Team chiefs whose teams were not in "ready" status planned, executed, and refined training for their teams under the guidance given by their supported commander. Organizing the on-base element under the leadership of the fifth sergeant first class allowed the commander and first sergeant to remain engaged with the operational planning, training management, and Soldier tasks required to make the plan function.

EXECUTING A READINESS EXERCISE

When 1-5 Cav officially assumed the strategic reserve mission two days after arriving in Kuwait, it executed an emergency deployment readiness exercise in the middle of the night. The smallest force package was alerted for air deployment and within three hours completed a mission rehearsal, movement by bus to the airfield, and pallet loading.

When the previous battalion executed its emergency deployment readiness exercise, its support company took 11 hours to find its support personnel and equipment, which effectively caused the whole unit to fail the exercise.

But 1-5 Cav's FSC had prepared under a mission command mindset. Its team chiefs had complete command and control over their teams. The support team loaded all supplies, equipment, and Soldiers within two hours. Because the junior leaders knew the mission and intent, the company's leaders were free to provide help where needed without having to micromanage packing lists, roll calls, or timelines.

Mission command enabled the FSC to add true value to the 1-5 Cav during a very stressful time in its deployment. The commander, first sergeant, and executive officer knew they would be unable to personally lead every mission that was to happen simultaneously in Kuwait. Therefore, they had to trust their leader development program and the decisions their geographically isolated leaders would make.

When the small team supporting the force left behind finally rejoined the 1-5 Cav in Kuwait two weeks later, the experiment was validated again. The infantry company's commander, first sergeant, and platoon leaders all went out of their way to say how much help the support team and the engaged, empowered team leader was to their organization. By having all the tools needed and the ability to maintain contact with the company's leaders, the team leader met the intent of seamless support despite his isolation from the FSC.

The concept was successfully used much later by the same unit in support of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. This serves as a proof of concept, showing that the details of the mission are immaterial. As long as leader development is the key theme in training, logistics units will be postured to excel in support of strategic landpower. Once leaders are trained and empowered, their skills do not expire, as shown by the success despite the passage of time.

Dozens of task organization methods could have been used to support the U.S. Forces-Iraq strategic reserve. However, what made the FSC's design so effective was the mission command attitude. The team chiefs had ultimate authority to support their operational commander based on the mission and intent given. They were not required to ask permission, which shortened the flash-to-bang time and gave them ownership of their teams. Adding staff sergeant experts to control the support tasks further enabled the team leaders' success.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Capt. Jon D. Mohundro is a strategic planner in the Training and Doctrine Command Commander's Planning Group. He is a logistics officer with eight years of experience, including an assignment as a forward support company commander in the 1st Cavalry Division.

Capt. Randall B. Moores is a student in the Combined Logistics Captains Career Course. He is a logistics officer with 6 years of experience, including an assignment as the S-4 of a combined arms battalion in the 1st Cavalry Division.

Capt. Patrick R. O'Reilly is S-4 of a combined arms battalion in the 1st Cavalry Division. He is a Quartermaster officer with 4 years of experience. He was previously assigned as a forward support company executive officer in the 1st Cavalry Division.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the March-April 2014 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing