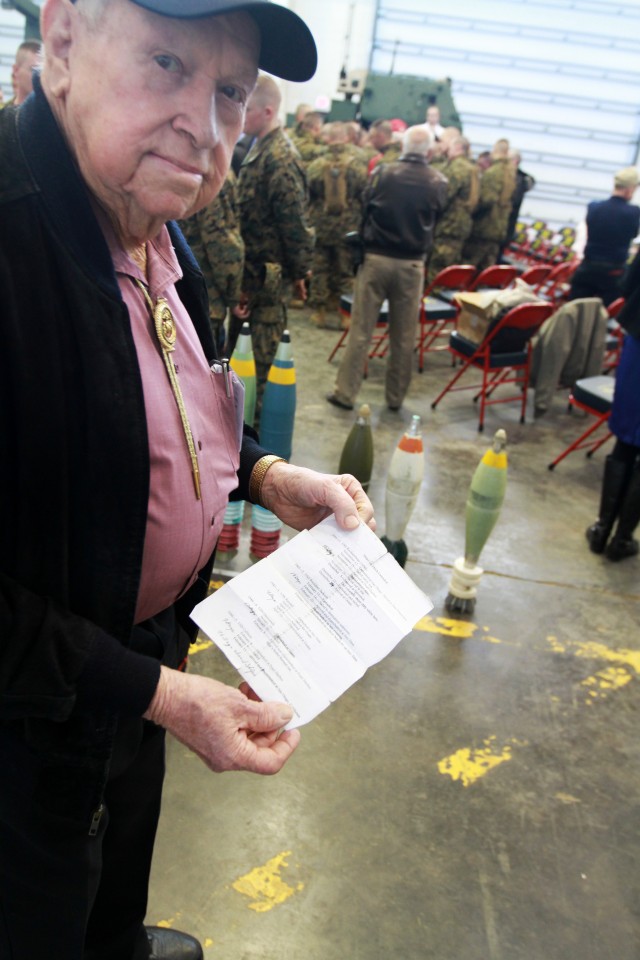

FORT SILL, Okla. -- Surrounded by a tight circle of camouflage, Hershel "Woody" Williams, had a group of young Marines captured. Hanging on his every word, the group drew closer and closer. Williams, a retired Marine and World War II Medal of Honor recipient, and other Iwo Jima survivors shared stories Feb. 13 in Powers Hall at Fort Sill.

"Iwo Jima is the legacy of the Marine Corps," said Pfc. Jonathan Hart. "Without Iwo Jima the Marine Corps wouldn't be what it is today."

Williams told the Marines who were about to enter training at Fort Sill, "Learn everything you can about your job; training, because you never know when you're going to have to use it. And, it could be the difference between survival and not survival."

One of only seven living Marine World War II MOH recipents, Woody received his for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as a demolition sergeant serving with the 21st Marines, 3rd Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, Feb. 23 1945.

Williams told the Marines how he was hit with shrapnel March 6, 1945, and called for a Navy corpsman to remove the metal from his leg. The corpsman removed it, tended to the wound, and told him to return to their ship.

"They would tag you and say 'OK you're out.' He put a tag on me and said 'You gotta go back,' and I said 'I'm not going back (to the ship).' So he started to walk away and I grabbed the tag and pulled it off and said 'I don't have a tag on me.' He turned around and I can 't repeat what he said to me, and anyway I stayed," said Williams.

The Marine Corps originally turned the war hero down because he didn't meet their 5-foot, 8-inch minimum height requirement. It wasn't until the Marines expanded their operations in the Pacific and changed it to 5-foot, 2-inches or better that he went on to serve.

"To me heighth was not a problem. At the time when I tried to get in the Marine corps in 1942 it was a problem, but it was their problem and not mine. I was 5'6" and gorgeous," said Williams. "The same guy that turned me down because I was too short, looked me up to say 'now do you want to go?' And I said 'of course, I still want to go.'"

His warfighting record goes on to say: "On one occasion, he daringly mounted a pillbox to insert the nozzle of his flamethrower through the air vent, killing the occupants and silencing the gun; on another he grimly charged enemy riflemen who attempted to stop him with bayonets and destroyed them with a burst of flame from his weapon.

"His unyielding determination and extraordinary heroism in the face of ruthless enemy resistance were directly instrumental in neutralizing one of the most fanatically defended Japanese strong points encountered by his regiment and aided vitally in enabling his company to reach its objective."

"The professionalism and the history of our Corps is very important to us and I think it's what makes Marines special is they pride themselves on being Marines, but they use examples and models from folks that went before them. All these stories just make them a better warfighter," said Col. Wayne Harrison, Marine Detachment commander.

Harrison said for him and his fellow Marines, meeting the survivors was like meeting a rockstar.

"It's better than watching movies. It's just an honor. It almost feels like you were there," said Pfc. Otilion Martinez. "Most people have grandparents who've been through war. I don't have any grandparents that I know of that went through any wars and to have stories like that to share I'm very emotional when it comes to stuff like that. I love hearing about it."

Williams said after everything he is been through, his biggest dream is that there will be no more war.

"I have the hope that somebody in this world will be smart enough at some point to say we can figure out how to get along with each other without having to kill each other. Somehow this country and other countries have got to find a peaceful way of solving our problems. It's just crazy you have to train people to kill other people. I still have hope. I'll never lose it," said Williams.

The group of Iwo Jima survivors left Fort Sill on their way to a reunion with more Marines.

"It really humbles you seeing the Medal of Honor around his neck. He must have gone through a lot and he's still here. There's not much I can say, except thank you," said Pfc. Jesus Geovanni Cruz-Pena.

On the way out, Williams made it known that he did not want any recognition for his service, but he wants another group deserved more recognition than they are receiving.

"That group of people are the Gold Star families: somebody who gave one of their own for our freedom. They gave more than I did, more than any survivor did in a sense."

Williams has started a nonprofit organization to try to erect a memorial in Washington, D.C. and across the United States in their honor.

Social Sharing