There's something about Redstone Arsenal and its engineer work force that keeps Bill Pittman coming to work each day.

Each day, that is, for 57 years.

This 87-year-old, World War II Marine veteran began his civilian career with the Army's rocket development team at Redstone Arsenal in 1951. He supported the 1953 history-making launch of the first Redstone rocket, which will celebrate the 55th anniversary of its first launch on Aug. 20.

Besides launching the nation's race to space, the Redstone rocket also launched the careers of American scientists and engineers at Redstone Arsenal, including Pittman, whose work has involved many of the rockets and missiles developed for the Army since the 1950s.

Yet, Pittman is the only engineer from those early rocket days still working for the Army or NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. In 1999, Pittman retired from his work at the Aviation and Missile Research Development and Engineering Center. But he still works daily at AMRDEC through the federal government's volunteer emeritus program.

When asked why he feels compelled to continue his work at AMRDEC, Pittman shrugged and said he still has "unfinished business."

"I feel a personal commitment to the work I've yet to finish here," said Pittman, looking around an office filled with mementoes from his fulfilling career. "I still want to strengthen the patent portfolio at AMRDEC and I am still working to support workshops by helping to seek out people who are willing to serve as chairmen and vice chairmen.

"I also enjoy being a mentor for younger engineers. We are fortunate to have some really sharp young people here dedicated to being engineers and scientists."

Pittman's career at Redstone Arsenal began in 1951, when, as a graduate of Mississippi State, he was recruited by the Army to work on rocket development at the Ordnance Missile Laboratories.

"It was the first time I had heard of the famous German rocket team," he said. "Mr. Hans Heuter was the senior mechanical engineer on the von Braun team. Personnel sent me to his office. He told me to sit down and then he called Personnel and said 'I need a mechanical engineer and you sent me this electroniker' (German reference for an electronics engineer)."

"I think he felt sorry for saying that in front of me because then he pulled out two big, thick documents that were declassified V-2 documents, and he told me to read them and report back to him."

It wasn't long before Pittman had proven his scientific and technical abilities to his German boss. He was put to work in the radio and telemetry group, which was housed in buildings located on what was then called Squirrel Hill (buildings 111 and 112 on Goss Road). He was the group supervisor for the telemetry system of the Redstone rocket, which was a direct descendent of the German's V-2 rocket.

"It was an exciting time," Pittman said of his work on the Redstone rocket. "At the time, we were in an international competition with the Russians. Von Braun had created such a vision. It was pretty revolutionary for our time."

Pittman rode down to Cape Canaveral in August 1950 with his then German boss, Otto Hoberg.

"We loaded our instruments in the back seat of his car and drove down together for the launch," he said. "When the systems were turned on for the temperature readings, you had to tune them up and wait for them to stabilize. I was the last one to come down from the missile when we closed the instrument hatch. We didn't know much about the effect temperatures had on components back then.

"As I was coming down from the missile, I passed von Braun who was getting his photograph taken. He asked me to explain to him about the temperature readings. I did my best and he said 'It's too complicated for me.' We all knew at that launch that we were going to be part of an historic event."

That first launch was considered a partial success by the team, with the rocket flying 8,000 yards from the missile range.

"We watched the missile go through a hole in the clouds," Pittman recalled. "Then, we heard a low rumble like it had burned out. We were standing near our trailer in the sand, and everyone jumped and ran to get a hiding place under the trailer. There was a burnout of carbon, but the launching proved our concept. It was successful because it proved our concept could launch a rocket. We knew it would lead to the next step."

Pittman attended two more launches of the Redstone rocket, one of which his wife Eloise also attended. From 1953 through 1958, 37 Redstones were fired to test structure, engine performance, guidance and control, tracking and telemetry. His work in support of the Redstone and other rockets involved studying the effects of the atmosphere on tracking systems.

"If you're going to track things in deep space then you had to know what was in space that could affect your tracking systems," he said. "It was all about understanding the ionosphere and rocket plasma effects."

The Redstone rocket engine went on to power the Jupiter C rocket that launched America's first orbiting satellite, Explorer I, in 1958. A Redstone rocket engine - known as "Old Reliable" -- also launched America's first astronaut in space - Alan Shepard - in 1961.

The Redstone rocket also had a significant role in the development of military missiles. As an Army field artillery theater ballistic missile, Redstone was known as the "Army's workhorse."

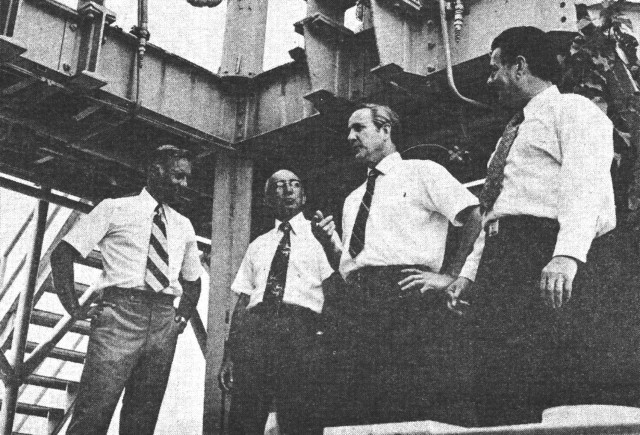

Pittman was among several American scientists and engineers who joined with the German rocket team to form the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in 1955. Pittman worked in the agency's Development Operations Division under the direction of Dr. Wernher von Braun.

Then, in 1958, NASA was created. In 1960, the German rocket team along with Pittman and many other American scientists and engineers became part of NASA's new Marshall Space Flight Center.

"It was a period of time filled with a sort of anxiety because we didn't know what the future was for our work. But we were too busy working to ponder it much," said Pittman, whose job title went from supervisor of electronics engineering to supervisor of aerospace engineering in the transition.

A year later, Pittman left MSFC to rejoin the civilian engineers at the Army's missile laboratories.

"There was never a dull moment," he said. "All these years, the work has not only been important for the defense of the country, but I think we have provided and are providing an important research foundation in advance technologies. Because of missile work here there has been a revolution in electronics and material sciences."

Pittman has been involved in the scientific research of many of the missiles developed and designed at Redstone Arsenal, including Hercules, Pershing and Hellfire. His name can be found on hundreds of research papers on missile technologies, and connected to many patents taking those technologies into the commercial realm.

He has received many accolades during his career. In 1994, he received the Meritorious Civilian Service Award (1986-93), the second highest award given to a Department of the Army civilian, for his work as a program manager in the Advanced Sensors Directorate, Research Development and Engineering Center. He has also received 12 performance awards, at least 40 commendation letters, a certificate of recognition from Maj. Gen. James Link and 14 U.S. patents.

Community organizations have also recognized Pittman. He is the recipient of the

Daughters of the American Revolution Medal of Honor and the Sons of the American Revolution Patriot Medal and Good Citizenship Medal and the Martin Schilling Award from the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. He has been active in several organizations and professional societies, including the Disabled American Veterans, First Marine Division Association, 9th Marine Defense Battalion Association, Association of the U.S. Army, Sons of the American Revolution, Institute of Radio Engineers, Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers and American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

As a volunteer at AMRDEC, Pittman is further developing a patent portfolio, and is working with engineers both at AMRDEC and with other local companies and organizations to promote research and development in missile fields.

"I think AMRDEC is in a very strong position as a hub of research and development," he said. "It has a long history of leading missile R&D and it's located in a city that has the second largest research park in the U.S. There's an enormous array of engineer and science talent at AMRDEC and in local industry and at the universities. And all of this wouldn't have happened without Redstone Arsenal and Marshall Space Flight Center."

Back in the 1950s, Pittman was a young engineer "thrown into a responsible position" in a new organization that has had a long-lasting impact on the nation's technologies. Today, young engineers are still being given responsibilities for research and development programs that have the potential of affecting the further advancement of science and technology.

"The Germans were good mentors back then. They told us to learn about all things, but to do one thing extremely well," he said. "I hope I have passed that along as a mentor to young engineers.

"I think a good engineer has to have a good foundation in physics and mathematics. And they should also have a good foundation in American and world history because it broadens their vision of the world. They should also have a respect for ethical standards. Those things provide for a foundation in the real advances in engineering."

Pittman hopes to stay on at AMRDEC "as long as I feel I'm being productive and the organization feels I am being productive."

He spends his free time with his wife, who is undergoing cancer treatment. He also enjoys time with his three children and five grandchildren, and he enjoys genealogy and history hobbies. He often writes book reviews of technical and history books.

"You got to stay active and productive," he said. "As long as I feel I'm being productive, I'll be here. I'm very fortunate to have made it this far."

Social Sharing