Soldiers and Civilians regularly attend briefings in the Holland Room in Fort Huachuca's Riley Barracks, or at the very least, pass by the portrait of Colonel Leland Holland every day on their way to their offices. Do any of them really know anything about the man behind the name?

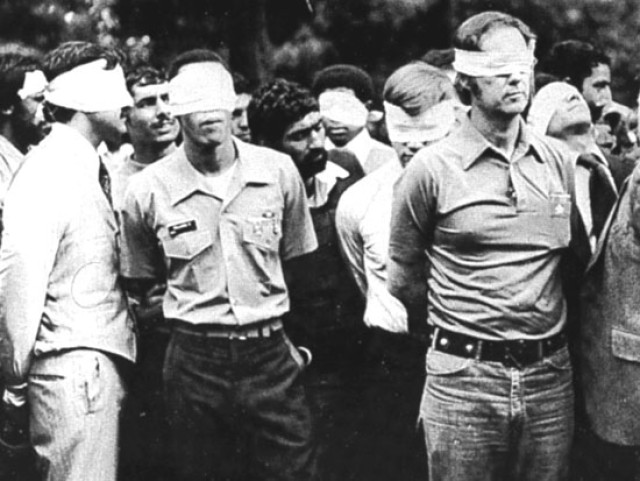

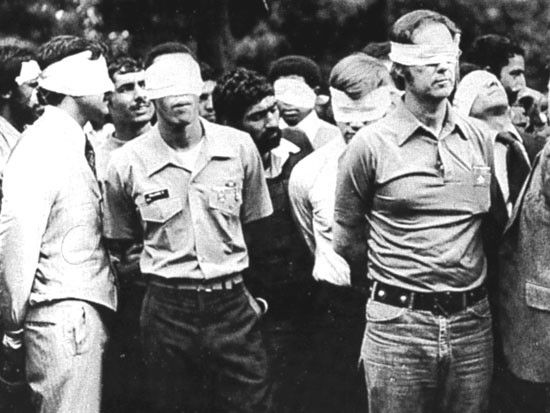

It was a quiet Sunday in November for most Americans. But halfway around the world, a mob was forming outside the gates of the US Embassy in Tehran, Iran. A group of about 150 members of the Muslim Students Association cut the heavy chains securing the gates of the embassy and made their way across the compound, securing the gates behind them. The Iranian police assigned to the compound made no efforts to stop them. What happened next was disturbing. While thousands of angry Iranians, with no clear purpose in mind, climbed the walls and forced their way into the Embassy compound, the students located the sixty-six US citizens inside, embassy personnel and a handful of Marine guards, blindfolded and tied their hands behind their backs. This was Day One: November 4, 1979. American journalist Walter Cronkite, night after night on American television, would count down the agonizingly long and humiliating number of days of captivity for the American hostages in Iran until they were freed, 444 days later.

The politics that led to this dramatic were set in motion when oil was discovered under Iranian sand in 1908. Over the course of two World Wars, the British government, with the help of the Soviets, worked to keep the oil away from the Germans. American leaders preferred to stay on the sidelines, pushing for an independent Iran, until it appeared that the Iranian leader was getting too close to the Soviets. For fear of that possibility, in 1953, the Central Intelligence Agency orchestrated a secret operation ousting the Iranian leader and putting Reza Shah Pahlavi into power with full backing of the American president. Prosperity followed for Iran, as its oil was sold around the world. But a growing resistance to Western influence, coupled with anger over the uneven distribution of wealth and power, led to the rise of a radical Islamic insurgency led by the cleric, Ayatollah Khomeini. As the Shah's popularity decreased over the years, the power and influence of the Ayatollah grew. Finally, a revolution in early 1979 deposed the Shah, sending him into exile, and Iran's fortunes were in the hands of radical, fundamentalist Muslims.

The deposed Shah was d

iagnosed with cancer in 1979 and his health was rapidly failing. No countries offered him asylum, until President Jimmy Carter, for humanitarian reasons, allowed him to enter the US for medical treatment in October 1979. This infuriated the militant extremists in Iran. Their takeover of the US embassy was in direct protest. They vowed to hold the Americans hostage until the ailing Shah was returned for trial and execution, and billions of dollars that they claimed he had stolen from the Iranian people was restored.

They very nearly kept their promise. The hostages were held for 444 days, through failed diplomacy, severe sanctions and oil embargoes, a botched rescue, and an increasingly impatient American public. President Carter was never to recover, politically. Even when Khomeini realized the futility of holding the hostages any longer, in September 1980, he kept the negotiations going until minutes after Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the new American president in January 1981.

One of those hostages was Colonel Leland Holland, assigned to Tehran as the Army Attaché to the US Embassy. Holland was no stranger to these scenarios. He had played a key role in the defense and subsequent liberation of the US Embassy and its personnel during a February 1979 attack by Iranian revolutionary forces. For his commendable efforts in that action Holland received a Distinguished Service Medal. But that attack lasted only hours. When the embassy was seized on November 4, 1979, Holland was the ranking military officer. His courage, temerity, and leadership would again be called into action, although this time he would spend 7 ½ months in solitary confinement, longer than any other military hostage. For his leadership and courage during this second ordeal, he was awarded the Defense Meritorious Service Medal. The citation reads, in part, "He served with discipline and demonstrated professional conduct under extremely adverse conditions as a captive. He lived up fully to the Code of Conduct, and continually demonstrated his personal qualities as a Soldier and as an American despite being subjected to mental and physical abuse by his captors."

After the hostage crisis finally ended, Colonel Holland served in the Pentagon as the Chief of Current Intelligence on the Army Staff. His final assignment was as Commander of Vint Hill Farms Station in Warrenton, Virginia, before he retired in 1987. Holland was inducted into the MI Hall of Fame in 1988. He died of cancer in 1990 and the US Army Intelligence Center memorialized him with the renaming of the Command Lab in Riley Barracks as the Holland Room. Hopefully, when current and future generations of Soldiers pass through and by that room, they will honor the memory and sacrifice of the man behind the name.

Social Sharing