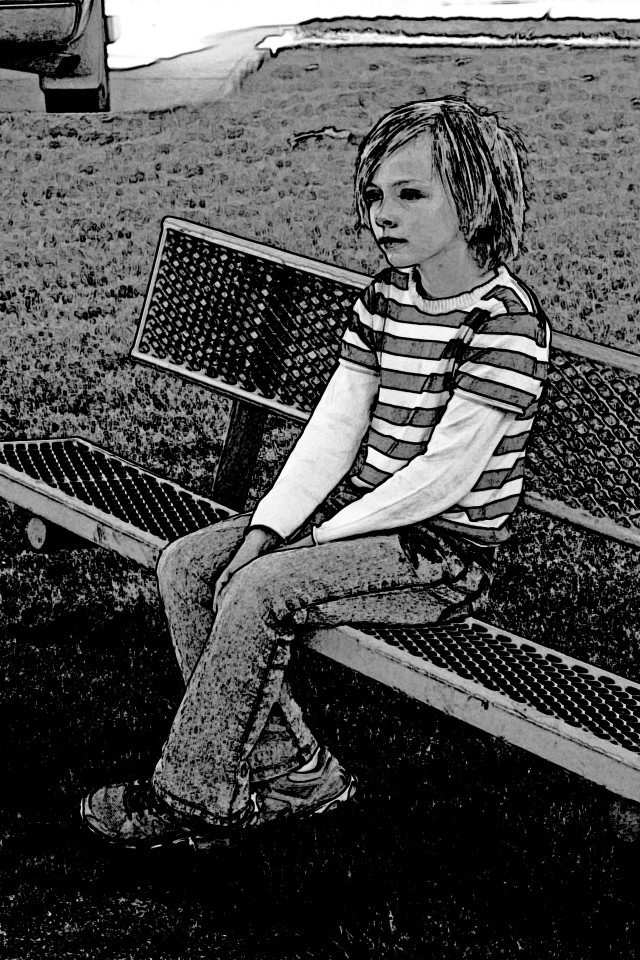

FORT CARSON, Colo. -- Bullying is an issue that can strike close to home.

At the middle school two years ago, a female student was having serious issues, struggling with school and fighting with her mother, said Felipe Nardo, school resource officer, Fort Carson police.

"They got her down to the hospital, got some help, and after speaking to the psychologist, (found out) she was being bullied for about six months, but she didn't say anything," he said.

Whether it's happening at school or in the neighborhood, parents can feel helpless in the face of bullying, unsure how to help their children or how to put a stop to it.

When bullying takes place in the schools, there are several options available.

"First of all, if they feel comfortable, just ask the bully to stop," Nardo said. "If that doesn't happen, let an adult know."

Once an adult is alerted to the situation, school officials investigate. Often, the situation can be handled internally.

"We'll sit down (with them) and mediate, (use) conflict management," said Steven Webb, Carson Middle School counselor. "Each kid gets a chance to tell their side of the story … and then we come to a solution."

If the bullying continues, or the bully tries to retaliate, there are consequences.

"We talk to the subject and let them know, if you continue to do that, we can charge you with a felony," Nardo said. They also get parents involved.

Students who are afraid of speaking up still have an option. They can call Safe 2 Tell, a 24/7 hotline answered by the Colorado State Patrol communications center. Students, parents and teachers can call to anonymously report bullying, threats, fights, substance abuse or other activities of concern. The report is then sent to the SRO and school administration to be dealt with.

"If you can't tell your mom or your teacher or your friend, you can call on your own. Immediately, we do an investigation," Nardo said.

If bullies refuse to stop bullying, and getting the parents involved doesn't resolve the situation, the last resort is to charge them with harassment.

"The last thing that I want to do is get kids in the system, so we try to work with them as much as we can," he said. "But if they're not listening to us or their parents, maybe the judge will get their (attention)."

Cyberbullying is an increasing problem, as well. Through text messages, Facebook and photo-sharing websites, bullies taunt their victims, and victims are sometimes hesitant to speak up.

"As far as cyberbullying, 'I don't want my parents to take away my cell phone. I don't want them to take away my computer,'" Nardo said, explaining the reasons why children don't tell anyone about the bullying.

If parents find that their children are being cyberbullied, they should bring it to the attention of the SRO, school administration or a counselor. If possible, they should get a screen shot, he said.

"Sometimes they wait for a couple (of)weeks, a couple (of) months," Nardo said. "If it happens, right away, as soon as it's happening, let us know. Then we can talk to the other person … and get it taken care of."

He recounted a situation in which a middle-school boy assaulted another boy in the gym.

"After speaking to him, (asking) why did it happen, he said this kid was picking on him for about four months, but nothing was said. He told his mom at the beginning … that he was being picked on, and they let it go," Nardo said. "Finally, this one day, he couldn't take it anymore and just punched (the other boy's) lights out."

The parents of the child who was hit pressed charges.

"If (the victim) would've come to us four months ago, (the bullying) would've been stopped," he said.

One of the difficulties in the schools is helping students to understand what bullying is and what it isn't.

"You have to figure out what's going on," Webb said. "Is it repetitive? Is it constant? Has it reached a physical point?"

Teasing, name calling, harassment and pushing can all be classified as bullying, if the actions continue over time. One-time incidents don't qualify as bullying, he said.

Parents also need to determine what role their own child played.

"A lot of times, it's a 50-50 thing, but parents don't always see it (that way)," said Kelly Boren assistant principal at Carson Middle School.

When dealing with a bully, Nardo recommends avoiding them as much as possible.

"Bullies like the audience," he said. "They like someone to react to what they're doing. If they can be ignored, I think that's one of the best things to do."

But when ignoring the bully doesn't work, school officials are there to help.

"We want the kids to feel safe here, and ultimately, we want them learning," Boren said. "If you don't feel safe, you're not going to learn."

Dealing with bullying in the villages requires more parental involvement.

The first step is for parents to speak with the other child's parents.

"I would expect the parent to handle it at their level, unless it's a constant issue, and they've exhausted their means," said Maj. Christopher Bolt, Fort Carson provost marshal, Directorate of Emergency Services.

That conversation can sometimes cause its own problems, depending on parents' response.

If discussing the issue doesn't work, Bolt recommends contacting the chain of command and notifying the housing office. Parents can also contact the MPs, who can do a report of entry, detailing the incident.

"The Soldier's chain of command would talk to the other Soldier's chain of command, letting that Soldier know, your son or daughter is bullying and you could lose your post privileges and be asked to move off post if it continues," he said.

Before it gets to that point, it would go through the garrison commander and command sergeant major first, he said.

"That's going to be the extreme case," Bolt said.

When incidents happen in the neighborhoods, police face several challenges in responding.

If there isn't sufficient evidence, police are limited in what actions they can take.

"What we can do is have our officers who respond let them know, this is what can happen if you're caught doing this, put a scare into them. But if the evidence isn't there, our hands are really tied," he said.

Police also need to weigh both sides of the story.

"When we respond to issues out in the villages, we look at both sides of the story and try to figure out what the truth is," he said. "There's always two sides to every story … I see it every day."

The situations in the villages on post often spill over into the schools, Bolt said.

"If it's happening at the (neighborhood) playground, then it's probably happening at school, too," he said. "Although it might be a middle schooler picking on an elementary school kid, but, at the end of the day, that middle schooler's probably being a bully at school, too."

Social Sharing