FORT BENNING, Ga., (Aug. 21, 2013) -- Nine-year-old Noah Ramirez is unable to maintain his weight, maintain vitals such as blood pressure, blood sugar levels and body temperature and suffers from gastroparesis -- a condition that slows or stops food from moving to the small intestines, said his mother, Tiffany Schumacker, a military spouse.

Because of these things, Noah requires total parenteral nutrition, which provides sustenance for those unable to get their foods through eating, a peripherally inserted central catheter, which goes from his arm to his heart, as well as a gastrostomy tube, which delivers nutrients to his stomach.

"When Noah gets sick, it's scary," she said, referring to how life threatening Mitochondrial Disease can be.

He has a doctor for almost every organ system, Schumacker said.

Aside from gastrointestinal problems, he has problems keeping up with other children his age because of extreme fatigue. And, Schumacker said, they keep their house temperature at 69 degrees, yet Noah still sweats.

WHAT IT IS

One thousand to 4,000 children are born each year with a mitochondrial disease, according to United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation.

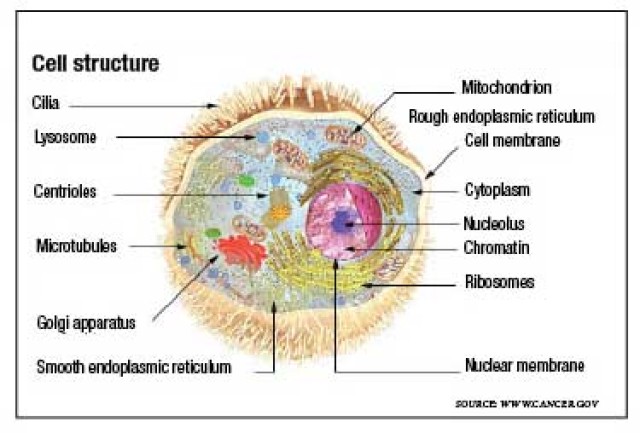

There are approximately 100 trillion cells in the human body. These cells make up each organ in the body -- including the skin, eyes, fingernails, intestines and heart. Each of these cells contains a mitochondrion -- also known as the power plant of the cell.

The mitochondrion converts sugar to energy so the cell is able to carry out its function. In people with the disease, the mitochondria are not able to produce the energy needed to keep the cell alive -- this causes the body's systems to malfunction or stop working.

LIVING WITH MITO

Wendy Loyd, chairperson for the Energy For Life Walkathon, knows all about the disease.

Wendy's daughter, 19-year-old Chelsea Loyd, also struggles to get things done in her daily life.

"I can go all day and do stuff, but usually within an hour of being out of the house I'm begging to come home," Chelsea said describing how fatigued she can get. "I watch a lot of TV, I listen to a lot of music -- that's one way I keep myself from getting depressed everyday. I went from being up at 8 o'clock in the morning doing school, cheerleading -- I would go running everyday, I'd baby-sit a couple of times -- I'd just be doing active stuff. I went from doing that to barely getting out of bed, going to school -- maybe three hours a day."

Chelsea saw multiple doctors before finding Dr. Paul LoDuca, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at Columbus Regional. Ramirez also sees LoDuca.

"When she (Chelsea) first came to me ... there was concern that she had leukemia because all of her counts were low," LoDuca said.

Chelsea didn't bounce back after an infection like normal people, he said. The inability to recover from an illness can raise a red flag.

Chelsea said after a recent breathing attack, she had no energy because her body used it trying to recover and open her airway.

"If you get too hot or too cold that burns energy (too) because your body can't regulate temperature," she said. "The smallest fever can be fatal."

Chelsea described her energy as having a set amount she could use, but had to use sparingly. She has to avoid others who are sick and said while in high school she was often removed from class if a person showed even the slightest signs of being sick.

There is no cure or treatment for the disease, Wendy Loyd said.

LoDuca said the current management of the illness is through a "mito cocktail," which includes many different pills with the hope there will be some improvement in the patient.

Because of the spectrum of symptoms patients can have, and the severity, it makes it hard to treat patients who often have a variety of problems, he said.

"One of the reasons why it's so hard to diagnose and to treat, is that people can present initially with anything," LoDuca said.

"(Chelsea) presented problems with the GI system at an early age. I've had other kids that presented with strokes right after delivery, other kids can have fatique -- there's lots of different things because it can affect everything.

He said the more the disease is understood, those who were treated for other diseases may eventually be diagnosed with a mitochondrial dysfunction.

"You have to take care of yourself because the littlest thing can be fatal to you," Chelsea said.

Chelsea said she is sometimes depressed because she doesn't feel normal and isn't able to keep up with her peers. She also calls the illness the "invisible disease," saying people have looked at her and said she looked as though there was nothing wrong with her.

She wants others to know that just because someone looks healthy, they may not be. And that is where the awareness comes in.

Wendy and Chelsea, started the local Energy For Life Walkathon to raise awareness in the Columbus community.

The walkathon is important to mito children and adults who, Chelsa said, are often overlooked because of the disease's invisibility. The walkathon is a way for those with the illness to get involved and be recognized.

Schumacker and her Family are also participating in the walkathon.

The walkathon is at 10 a.m. Sept. 14 at Golden Park and Riverwalk.

"When he (Noah) found out about the walk … his eyes lit up," she said.

They have created a team for the walk -- Team Noah.

"He's very involved in it," she said. "He thinks that it is really awesome that there are people who are willing to help."

MOVING FORWARD

The illness is overlooked, even among doctors, Schumacker said. She often has to explain mito to doctors every time she and her Family PCS to a new installation. Being a military Family can create some issues for the Family as they PCS every two years -- which means having to find new doctors for Noah, she said.

Schumacker said doctors could be skeptical and want to run their own tests, especially if they are unfamiliar with the disease.

"A lot of times you will start to think you are crazy," she said. "You think you are seeing things … because people will look at you and say 'that's not possible.' Labs would always come back normal."

But its parents who know their children best, she said.

"Parents see them every day… doctors see them (less)," Schumacker said. "They are not there to see them everyday. You are your child's biggest advocate."

Schumacker copes with her son's disease by staying on top of research, she said. But that doesn't stop her Family from enjoying their lives as normal as possible.

"We try to treat him as normal as possible," she said. "He still has chores, he still is disciplined the same as the other two kids. My husband still plays with him like the other kids."

Kids who have serious illnesses are usually more mature about their medical condition than others their age, she said.

"Noah can tell you almost everything about his medical condition," Schumacker said.

Schumacker also receives a lot of support from doctors and nurses willing to help her and her Family. When it's time for the Family to PCS, it will be hard Schumacker said.

"Dr. LoDuca, has been a life-saver for us here," she said. "We're going to have to go to another place and tell our story," she said. "We have to start over every time we move. When we go to the next base -- those same doctors and nurses aren't going to be there."

Schumacker said each PCS is scary because Noah has developed trust in the providers he sees and when they PCS the Family will have to rebuild relationships and support groups.

After a recent hospital visit, Schumacker said, Noah began showing some weight gain. She hopes he will be able to thrive without the TPN.

Chelsea is currently not in college, but said she will attempt to start in January.

For more information, visit www.energyforlifewalk.org/columbusga.

Social Sharing