Creation of the Women's Army Corps

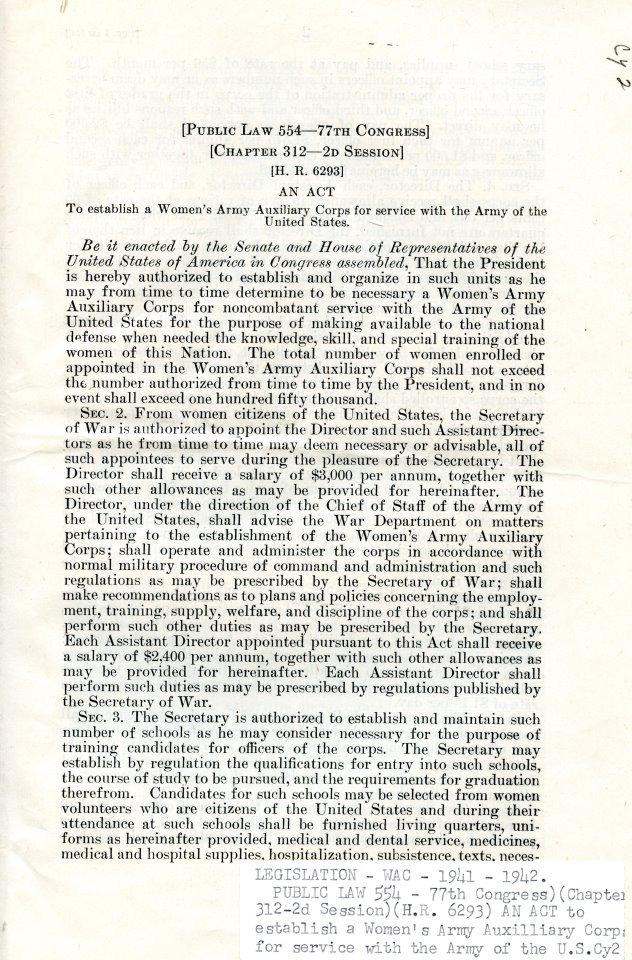

Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC)

With war looming, U.S. Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill for the creation of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in May 1941. Having been a witness to the status of women in World War I, Rogers vowed that if American women served in support of the Army, they would do so with all the rights and benefits afforded to Soldiers.

Spurred on by the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Congress approved the creation of WAAC on May 14, 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law on May 15, and on May 16, Oveta Culp Hobby was sworn in as the first director. WAAC was established "for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of women of the nation."

on May 15, and on May 16, Oveta Culp Hobby was sworn in as the first director. WAAC was established "for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of women of the nation."

WAAC adopted Pallas Athene, Greek goddess of victory and womanly virtue - wise in peace and in the arts of war - as its symbol.

Pallas Athene and the traditional "U.S." were worn as lapel insignia. Cap insignia was an eagle, adapted from the design of the Army eagle. The WAAC eagle, later familiarly known as "the Buzzard," was also imprinted on the plastic buttons of the uniform.

Recruitment and Training

Hobby immediately began organizing the WAAC recruiting drive and training centers. Fort Des Moines, Iowa, was selected as the site of the first WAAC Training Center. Over 35,000 women from all over the country applied for less than 1,000 anticipated positions.

The first women arrived at the first WAAC Training Center at Fort Des Moines on July 20, 1942. Among them were 125 enlisted women and 440 officer candidates (40 of whom were black), who had been selected to attend the WAAC Officer Candidate School, or OCS. Their arrival and subsequent training brought considerable public interest surrounding civil rights, as this corps presented the biggest opportunity to test integration in the Army. After OCS, black officers and white officers were segregated.

After training, the WAAC officer or enlisted person was assigned to a 150-woman table of organization company, which only had spaces for clerks, typists, drivers, cooks and unit cadre. Women primarily worked in four fields: baking, clerical, driving and medical. Within one year of the WAAC establishment, over 400 jobs were open to women.

Members of the WAAC work in the motor pool at Fort Huachuca!, 1943. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Women's Museum)

WAAC recruiting postcard and poster, entitled “THIS IS MY WAR TOO!” (Courtesy of U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center)

Since to the WAAC law did not women an integral part of the Army, they could not be governed by Army regulations or the Articles of War. Stateside, enlisted women and men received the same basic rate of pay. However, women could not receive overseas pay and were ineligible for government life insurance. If they were killed, their parents could not collect the death gratuity.

In the beginning, WAAC exceeded all its recruiting goals, but by June 1943, recruiting efforts had fallen. Higher paying jobs in civilian industry, unequal benefits with men, and attitudes within the Army itself - which had existed as an overwhelmingly male institution from the beginning - were factors.

Conversion to Army status, Women's Army Corps (WAC)

In January 1943, U.S. Rep. Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced identical bills in both houses of Congress to permit the enlistment and commissioning of women in the Army of the United States, or Reserve forces, as opposed to regular enlistments in the U.S. Army. This would drop the "auxiliary" status of the WAAC and allow women to serve overseas and "free a man to fight."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the legislation on July 1, 1943, which changed the name of the Corps to the Women's Army Corps (WAC) and made it part of the Army of the United States. This gave women all of the rank, privileges, and benefits of their male counterparts.

Women were recruited from all 50 states and territories. A WAC recruiting campaign on the island of Puerto Rico resulted in 200 women being selected out of a pool of 1500. Entrance requirements were rigorous, with each woman required to pass an exam that was entirely in English. Those selected represented many professions: teachers, office workers, translators and even a lawyer.

Women's Army Corps also recruited Nisei women, or second-generation Japanese-American women. Several hundred were selected, and a number of these trained in linguistics at the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Other Nisei WACs received more traditional training in clerical, medical, and supply positions. Eventually, some Nisei WACs found themselves serving as translators and officer workers at Gen. Douglas MacArthur's headquarters in Tokyo.

During World War II, members of WAC were assigned to the Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, and the Army Service Forces - comprised of nine service commands, the Military District of Washington and the Technical Services. At first, job opportunities were limited, but soon wide arrays of positions were available to women.

Army Air Forces (AAF)

Assigned as: weather forecasters and observers, electrical specialists, sheet metal workers, link trainer instructors, control tower specialists, airplane mechanics, photo-laboratory technicians and photo interpreters.

Army Ground Forces (AGF)

Assigned to Armor and Cavalry Schools and worked as radio mechanics, took care of records and requisitions involving radio equipment, repaired and installed radios in tanks, bantams and other vehicles - both in camps and in bivouac areas, and trained men in field artillery and code sending and receiving.

Army Service Forces (ASF)

The Signal Corps used women as telephone, radio and teletype operators, cryptographers, cryptanalysts, and photographic experts. The Technical Service, employed under the Transportation Corps, utilized assistance in processing troops and mail. Women served as medical and surgical technicians served within the medical department, and also conducted administrative services for Adjutant General's Corps, Chemical Warfare Service, Quartermaster Corps, finance department, provost marshal and Corps of Chaplains.

In 1944, as Allied forces took the initiative both in Europe and the Far East, WAC units moved into support areas behind the combat troops. January 1944 marked the arrival of the first WAC, in the Pacific theater of operations, at New Caledonia. In May 1944, the first contingent assigned to the Southwest Pacific arrived in Sydney, Australia. Landing crafts put WACs ashore on the Normandy beachhead during July 1944, while others began assuming duties in the China-Burma-India theater. The women of the Corps went where they were needed – to Oro Bay, Hollandia, Casablanca, Chunking, and Manila.

Victory in Europe, victory over Japan and the end of World War II

Victory in Europe was proclaimed when German Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, of the German High Command, signed the terms of an unconditional surrender in Reims, France, May 7, 1945. Similarly, Victory in Japan was proclaimed on Sept. 2, 1945, to celebrate Japan's acceptance of unconditional surrender terms that occurred on Aug. 14, 1945.

After the war, WAACs had no legal re-employment rights, no peacetime component or even an inactive Reserve. Without these rights, jobs for women would be scarce in peacetime. For this reason, Hobby favored disbanding the WAC as soon as the war ended. Congress provided re-employment rights for WAACs and WACs on Aug. 9, 1946.