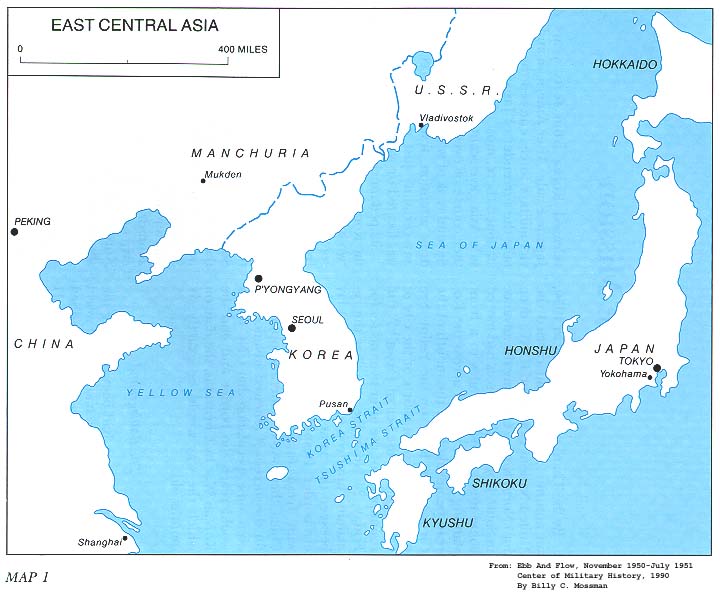

Surviving the Holocaust, Serving in the Korean War

Tibor "Ted" Rubin knows what it's like to slowly starve to death, how lice itch when crawling over skin and how giving up on life can seem easier than fighting for it. Nazi guards made sure Rubin understood despair at the age of 13. A Hungarian Jew, he was forced into the Mauthausen Concentration Camp toward the end of World War II. But Rubin defied odds: He survived. After the war he moved to New York, and eventually joined the same Army that liberated him from hell on earth.

An M8 Greyhound armored car of the US Army's 11th Armored Division entering the Mauthausen concentration camp. The banner in the background (in Spanish) reads as "Anti-fascist Spaniards salute the forces of liberation. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration."

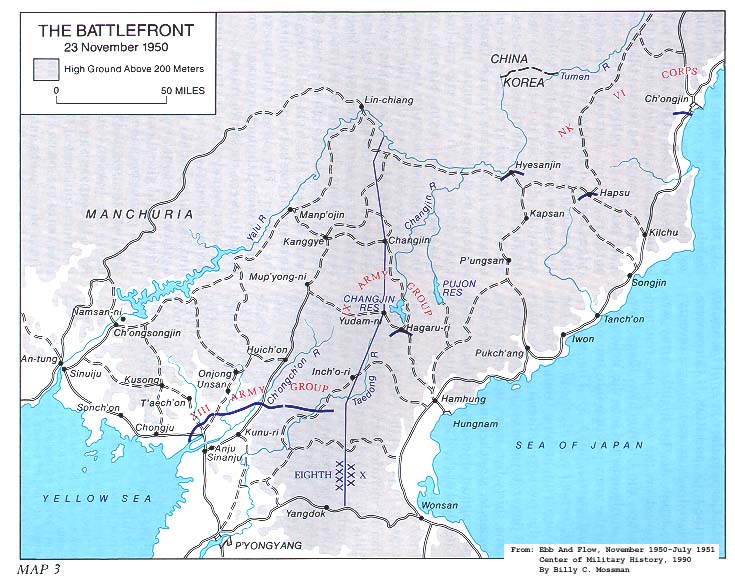

From the horror of the Holocaust arose a bravery that few can match. Rubin went on to fight in the Korean War and was taken prisoner by the Chinese. This time, he breathed life into his fellow captives, who were dying at the rate of 40 a day in the winter of 1950-1951.

Life as a prisoner under the Nazis and the Chinese are incomparable for Rubin. Of his Chinese captors, Rubin says only that they were "human" and somewhat lenient. Of the Nazis, Rubin remains baffled by their capacity to kill. He was just a boy when he lost his parents and two little sisters to the Nazi's brutality. "In Mauthausen, they told us right away, 'You Jews, none of you will ever make it out of here alive'," Rubin remembers. "Every day so many people were killed. Bodies piled up God knows how high. We had nothing to look forward to but dying. It was a most terrible thing, like a horror movie." American Soldiers swept into the camp on May 5, 1945, to liberate the prisoners. It is still a miraculous day for Rubin, indelibly imprinted in his heart. "The American Soldiers had great compassion for us. Even though we were filthy, we stunk and had diseases, they picked us up and brought us back to life." Rubin made a vow that day that he's fulfilled ten times over.

"I made a promise that I would go to the United States and join the Army to express my thanks," said Rubin. Three years later he arrived in New York. Two years after that he passed the English language test — after two attempts and with "more than a little help," he jokes — and joined the Army. He was shipped to the 29th Infantry Regiment in Okinawa. When the Korean War broke out, Rubin was summoned by his company commander. "The 29th Infantry Regiment is mobilizing. You are not a U.S. citizen so we can't take you — a lot of us are going to get killed. We'll send you to Japan or Germany," Rubin remembers being told.

"But I could not just leave my unit for some 'safe zone,'" Rubin said. "I was with these guys in basic training. Even though I wasn't a citizen yet, America was my country." Rubin got what he wanted and headed for Korea. Cpl. Tibor Rubin deployed to Korea on February 13, 1950 as a part of I Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.

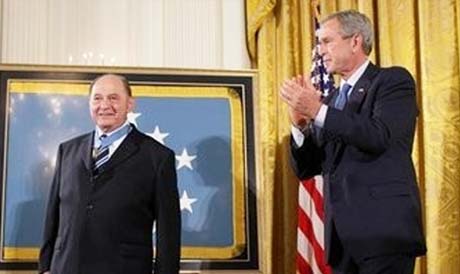

"He saved a lot of GI's lives. He gave them the courage to go on living when a lot of guys didn't make it," said Sgt. Leo Cormier, a fellow POW. "He saved my life when I could have laid in a ditch and died — I was nothing but flesh and bones." Rubin was nominated for the Medal of Honor four times by grateful comrades. While most military decorations are awarded for a single act, Rubin's was earned by courage that withstood battle on the front lines, and then thrived in the face of death for two and a half years. "People ask, 'How the hell did you get through all that?'" said Rubin. "I can't answer, but I figured whatever I did, I was never going to make it out alive."

The personal character of Corporal Rubin and his “call to duty” are exemplified in this quote:

“I always wanted to become a citizen of the United States and when I became a citizen it was one of the happiest days in my life. I think about the United States and I am a lucky person to live here. When I came to America, it was the first time I was free. It was one of the reasons I joined the U.S. Army because I wanted to show my appreciation.”

Rubin received the Prisoner of War Medal after being held as a POW in North Korea for 30 months and two Purple Hearts during his service.

Ted Rubin's life before and after service in the Army

Rubin is a survivor of 14 months in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Liberated by the U.S. Army, he credits Army medics for saving the lives of survivors. He notes, “I thank God that I came to the United States.”

He follows a legacy of military service in his family — his father, Ferenz, was a Soldier in the Hungarian Army and a hero in World War I, and was a prisoner of war in Russia for over six years. During WWII, his father was moved to Auschwitz and later to Buchenwald where he died. Rubin's uncle was also a POW. His mother, Rosa and 10-year-old sister Elonja died in a gas chamber in Auschwitz, Germany. His older brother, Mike Lesak fought with the English and Czech in World War II.

Rubin worked as a butcher before he entered the Army, but his war injuries prevented him from continuing. He worked as a clerk and later as a manager at a liquor store owned by his brother, Emery I. Rubin. Emery is also a survivor of a concentration camp. Later, Emery brought on Ted as a partner at a liquor store.

He became an American citizen between 1953-1954 — the exact date is unknown. Rubin had two children with his wife, Yvonne. His son, Frank, served four years in the U.S. Air Force and is employed at the Veteran's Administration in Long Beach, California. Rubin's daughter, Rosalyn, has worked as a school teacher. Rubin traveled all over the world to include: Turkey (to visit his POW friends), Israel, Italy, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, Austria, Mexico, Sweden and Norway. His hobbies included reading and talking with people. He enjoyed soccer, chess and ping-pong, and competed as an amateur boxer in his younger days in Germany.

When admired for his courage, Rubin was quick to wave off praise. His acts had more to do with his vow to serve than with heroism, he said. "The real heroes are those who never came home. I was just lucky," Rubin said. "This Medal of Honor belongs to all prisoners of war, to all the heroes who died fighting in those wars."

And Rubin couldn't forget the Jews who died in vain, or the American Soldiers who made survivors of the rest. To them, he dedicated the best years of his life, becoming an American war hero — a Soldier of uncommon bravery.

Rubin died on December 5, 2015 at the age of 86 in Garden Grove, California.

Rubin, lying down with a blanket over him, talks to reporters upon his release from the Communist prisoner of war camp. Although life in the camp was difficult, he told reporters from Stars and Stripes that the Chinese treated him much better than the Germans had. Photo used with permission from Stars and Stripes.