Introduction

The Korean War was the first major armed clash between Free World and Communist forces, as the so-called Cold War turned hot. The half-century that now separates us from that conflict, however, has dimmed our collective memory. Many Korean War veterans have considered themselves forgotten, their place in history sandwiched between the sheer size of World War II and the fierce controversies of the Vietnam War. The recently built Korean War Veterans Memorial on the National Mall and the upcoming fiftieth anniversary commemorative events should now provide well-deserved recognition. I hope that this series of brochures on the campaigns of the Korean War will have a similar effect.

The Korean War still has much to teach us: about military preparedness, about global strategy, about combined operations in a military alliance facing blatant aggression, and about the courage and perseverance of the individual soldier. The modern world still lives with the consequences of a divided Korea and with a militarily strong, economically weak, and unpredictable North Korea. The Korean War was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over and near the Korean peninsula. It lasted three years, the first of which was a seesaw struggle for control of the peninsula, followed by two years of positional warfare as a backdrop to extended cease-fire negotiations. The following essay is one of five accessible and readable studies designed to enhance understanding of the U.S. Army’s role and achievements in the Korean conflict.

During the next several years the Army will be involved in many fiftieth anniversary activities, from public ceremonies and staff rides to professional development discussions and formal classroom training. The commemoration will be supported by the publication of various materials to help educate Americans about the war. These works will provide great opportunities to learn about this important period in the Army’s heritage of service to the nation.

This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Richard W. Stewart. I hope this absorbing account, with its list of further readings, will stimulate further study and reflection. A complete listing of the Center of Military History’s available works on the Korean War is included in the Center’s online catalog: http://www.history.army.mil/catalog/index.html.

JOHN

S. BROWN

Brigadier General, USA

Chief of Military History

2

The Chinese Intervention

3 November 1950-24 January 1951

They came out of the hills near Unsan, North Korea, blowing bugles in the dying light of day on 1 November 1950, throwing grenades and firing their "burp" guns at the surprised American soldiers of the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division. Those who survived the initial assaults reported how shaken the spectacle of massed Chinese infantry had left them. Thousands of Chinese had attacked from the north, northwest, and west against scattered U.S. and South Korean (Republic of Korea or ROK) units moving deep into North Korea. The Chinese seemed to come out of nowhere as they swarmed around the flanks and over the defensive positions of the surprised United Nations (UN) troops. Within hours the ROK 15th Regiment on the 8th Cavalry’s right flank collapsed, while the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 8th Cavalry fell back in disarray into the city of Unsan. By morning, with their positions being overrun and their guns falling silent, the men of the 8th Cavalry tried to withdraw, but a Chinese roadblock to their rear forced them to abandon their artillery, and the men took to the hills in small groups. Only a few scattered survivors made it back to tell their story. The remaining battalion of the 8th Cavalry, the 3d, was hit early in the morning of 2 November with the same "human wave" assaults of bugle-blowing Chinese. In the confusion, one company-size Chinese element was mistaken for South Koreans and allowed to pass a critical bridge near the battalion command post (CP). Once over the bridge, the enemy commander blew his bugle, and the Chinese, throwing satchel charges and grenades, overran the CP.

Elements of the two other regiments of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 5th and 7th Cavalries, tried unsuccessfully to reach the isolated battalion. The 5th Cavalry, commanded by then Lt. Col. Harold K. Johnson, later to be Chief of Staff of the Army, led a two-battalion counterattack on the dug-in Chinese positions encircling the 8th Cavalry. However, with insufficient artillery support and a determined enemy, he and his men were unable to break the Chinese line. With daylight fading, the relief effort was broken off and the men of the 8th Cavalry were ordered to get out of the trap any way they could. Breaking into small elements, the soldiers moved out overland under cover of darkness. Most did not make it. In all, over eight hundred men of the 8th Cavalry were lost—almost one-third of the regiment’s strength—in the initial attacks by massive Chinese forces, forces that only recently had been considered as existing only in rumor.

3

4

U.S. soldiers with tank make their way through the rubble-strewn streets

of Hyesanjin in November 1950. (DA photograph)

Other elements of the Eighth Army were also attacked in the ensuing days, and it fell back by 6 November to defensive positions along the Ch’ongch’on River. However, as quickly as they had appeared, the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) disappeared. No additional attacks came. The Chinese units seemed to vanish back into the hills and valleys of the North Korean wastelands as if they had never been. By 6 November 1950, all was quiet again in Korea.

Strategic Setting

The large-scale Chinese attacks came as a shock to the allied forces. After the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter and the Inch’on landings, the war seemed to have been won. The desperate defensive fighting of June was a distant memory, as were the bloody struggles to hold the Naktong River line in defense of Pusan in August and early September. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the Far Eastern Command Theater Commander, had triumphed against all the odds by landing the X Corps, consisting of the 1st Marine Division, the 7th Infantry Division, and elements of ROK Marines at the port of Inch’on

5

near Seoul on 15 September. Breaking out from the Pusan Perimeter four days later, Eighth Army defeated and then pursued the remnants of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) up the peninsula by many of the same roads over which they had retreated a mere two months before. On 29 September Seoul was declared liberated.

As the victorious UN forces pursued the fleeing NKPA, MacArthur was authorized by President Harry S. Truman to go north of the pre-June boundary, the 38th Parallel, while enjoined to watch for any indications that the Soviets or Chinese might enter the war. Korea was seen by most at the time as just part of the overall struggle with world communism and perhaps as the first skirmish in what was to be World War III. MacArthur, convinced that he could reunify all of Korea, moved his forces north. Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker’s Eighth Army advanced up the west coast of Korea to the Yalu River, while Maj. Gen. Edward M. "Ned" Almond’s independent X Corps conducted amphibious landings at Wonsan and Iwon on the east coast. Almond’s units moved up the coast and to the northeast and center of Korea to the border with China. Until the attacks by the CCF at Unsan, the war thus seemed on the verge of ending with the UN forces merely having to mop up NKPA remnants.

In retrospect the events on the battlefield in late October and early November 1950 were harbingers of disaster ahead. They had been foreshadowed by ominous "signals" from China, signals relayed to the United States through Indian diplomatic channels. The Chinese, it was reported, would not tolerate a U.S. presence so close to their borders and would send troops to Korea if any UN forces other than ROK elements crossed the 38th Parallel. With the United States seeking to isolate Communist China diplomatically, there were very few ways to verify these warnings. While aware of some of the dangers, U.S. diplomats and intelligence personnel, especially General MacArthur, discounted the risks. The best time for intervention was past, they said, and even if the Chinese decided to intervene, allied air power and firepower would cripple their ability to move or resupply their forces. The opinion of many military observers, some of whom had helped train the Chinese to fight against the Japanese in World War II, was that the huge infantry forces that could be put in the field would be poorly equipped, poorly led, and abysmally supplied. These "experts" failed to give full due to the revolutionary zeal and military experience of many of the Chinese soldiers that had been redeployed to the Korean border area. Many of the soldiers were confident veterans of the successful civil war against the Nationalist Chinese forces. Although these forces were indeed poorly supplied, they were highly motivated, battle hardened, and led by officers who were veterans, in some cases, of twenty years of nearly constant war.

6

Perhaps the most critical element in weighing the risks of Chinese intervention was the deference paid to the opinions of General MacArthur. America’s "proconsul" in the Far East, MacArthur was the American public’s "hero" of the gallant attempt to defend Bataan and Corregidor in the early days of World War II, the conqueror of the Japanese in the Southwestern Pacific, and the foreign "Shogun" of Japan during the occupation of that country. He was also the architect of the lightning stroke at Inch’on that almost overnight turned the tide of battle in Korea. When he stated categorically that the Chinese would not intervene in any large numbers, all other evidence of growing Chinese involvement tended to be discounted. MacArthur and his Far Eastern Command (FEC) intelligence chief, Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, continued to insist, despite the CCF attacks at Unsan and similar attacks against X Corps in northeastern Korea, that the Chinese would not intervene in force. On 6 November the FEC continued to list the total of Chinese troops in theater as only 34,500, whereas in reality over 300,000 CCF soldiers organized into thirty divisions had already moved into Korea. The mysterious disappearance of Chinese forces at that time seemed only to confirm the judgment that their forces were only token "volunteers."

The overall situation in early November 1951 was unsettled, but UN forces were still optimistic. The North Korean Army had been thoroughly defeated, with only remnants fleeing into the mountains to conduct guerrilla warfare or retreating north toward sanctuary in China. Eighth Army positions along the Ch’ongch’on River, halfway between the 38th Parallel and the Yalu, were strong. The 1st Cavalry Division had admittedly taken a beating, but two regiments were still in good condition, while the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions had generally recovered from their earlier trials. On the Eighth Army’s right flank, the 2d Infantry Division was in a position to backstop the vulnerable ROK 6th and 8th Divisions. In northeastern Korea, the units under X Corps were fresh and, in the case of the 1st Marine Division, at full strength. By the first week of November, despite the surprise attacks by what were still classed as small Chinese volunteer units, the United Nations forces as a whole were well positioned and looking forward to attacking north to the Yalu to end the war and being "home by Christmas."

Operations

The U.S.-led United Nations Command (UNC) had extensive forces at its disposal in Korea in November 1950. The major UNC

7

ground combat strength consisted of Eighth Army headquarters, a ROK army headquarters, 6 corps headquarters (3 U.S., 3 ROK), 18 infantry division equivalents (10 ROK, 7 U.S. Army, and 1 U.S. Marine), 3 allied brigades, and a separate airborne regiment. The total combat ground forces were around 425,000 soldiers, including some 178,000 Americans. In addition, of course, the UNC had major air and naval components in support.

Forces opposing the UN in early November were organized under a combined headquarters staffed by North Korean and Chinese officers. Kim Il Sung, the leader of North Korea, was also commander of the North Korean Armed Forces based at Kanggye, deep in the mountains of north central Korea. On paper, the North Korean forces consisted of 8 corps, 30 divisions, and several brigades, but in fact only 2 corps totaling some 5 weak divisions and 2 depleted brigades were in active operations against UN forces. The IV Corps with one division and two brigades opposed the ROK I Corps in northeastern Korea, while the II Corps with 4 scattered and weakened divisions was engaged in guerrilla operations in the Taebaek Mountains both above and below the 38th Parallel. The remainder of the surviving North Korean Army elements were resting and refitting in the sanctuary of Manchuria or along the border in north central Korea, away from the main lines of UN advance along the east and west coasts of the peninsula. Most of the enemy striking power was contained in the 300,000-strong Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA). They had entered Korea during the last half of October, undetected by FEC intelligence assets. The stage was set for the near-destruction of Eighth Army and the abandonment of the military attempt to reunify Korea.

Convincing himself and his Far Eastern Command staff that the Chinese would not intervene in force, General MacArthur was determined to reunify Korea and change the balance of power in Asia. The Joint Chiefs of Staff, impressed by MacArthur’s stunning triumph at Inch’on and the collapse of the NKPA during the following month, were in no position to argue. Despite some misgivings, they allowed MacArthur a generous, although not unrestrained, latitude to pursue his vision of winning the war before the year was out. Even President Truman, not a man to defer easily to anyone, apparently felt that MacArthur should be allowed to carry on the war and finish off the North Koreans.

To implement MacArthur’s objectives, General Walker drafted plans for his Eighth Army to advance quickly against the crumbling opposition all the way to the Yalu River on the Chinese frontier. Meanwhile, General Almond and his X Corps, separated from Eighth

8

9

Army by the virtually impassable Taebaek Mountains, planned a similar series of widely scattered offensive spearheads on the eastern side of the peninsula in order to beat Eighth Army to the Yalu. Beginning in mid-October, each major force sought to take as much terrain as possible. Eighth Army units occupied P’yongyang, the North Korean capital, about seventy-five miles north of the 38th Parallel, on 19 October. Almond’s X Corps came ashore at Wonsan on the other side of the peninsula on 25 October and moved quickly inland. Only the unforeseen incidents at Unsan, about sixty miles north of P’yongyang, at the end of October caused both forces to pause and reconsider the wisdom of such an all-out offensive.

With the cessation of Chinese attacks on 6 November, Walker and Almond began planning to resume the offensive. Elements of X Corps units even reached the Yalu River at Hyesanjin on 21 November and Singalp’ajin on the twenty-eighth. Although these were only minor "reconnaissance-in-force" elements, both Walker and Almond planned to follow through with major offensives of all their forces beginning on 24 and 27 November, respectively.

In the west, Eighth Army began its offensive north from its positions along the Ch’ongch’on River, some fifty miles north of P’yongyang, on 24 November. Its initial objective was to reestablish contact with any remnant North Korean forces or Chinese volunteer units. The I Corps (24th Infantry Division, ROK 1st Infantry Division, and British 27th Commonwealth Brigade) was on Eighth Army’s left, IX Corps (25th Infantry Division, 2d Infantry Division, and the Turkish Brigade) was in the center, while the ROK II Corps, with its 6th, 7th, and 8th Infantry Divisions, was on the eastern flank. The 1st Cavalry Division and the British 29th Infantry Brigade were in reserve, along with the U.S. 187th Regimental Combat Team (Airborne).

The I Corps attacked west and northwest toward Chongju and T’aech’on, while IX Corps headed north toward Unsan, Onjong, and Huich’on. The ROK II Corps began moving toward the northeast and into the Taebaek Mountains on the Eighth Army’s right flank that separated Eighth Army from X Corps. All advancing units generally received only scattered small-arms fire, and in most instances they moved unopposed toward their objectives. A few miles from Unsan, elements of the 25th Division discovered thirty U.S. soldiers missing since the 8th Cavalry’s battle with the Chinese weeks before. They had been captured and then released by the Chinese and suffered from wounds and frostbite, but they were alive. By 25 November all units were reporting that they had reached their objectives, although they

10

also reported increasing enemy resistance and even some local counterattacks. However, optimism still prevailed. Eighth Army thus planned to resume its offensive in conjunction with the planned attack of X Corps in the east beginning on 27 November.

The Battles Along the Ch’ongch’on

On the night of 25 November the Chinese struck Eighth Army again. The first CCF attacks hit the 9th and 38th Infantries of the U.S. 2d Infantry Division about eighteen miles northeast of Kunu-ri along the Ch’ongch’on River. Charging to the sounds of bugles, the Chinese 40th Army found gaps between the units and struck their flanks. They hit units on both sides of the river just south of a low mountain called, ironically, Chinaman’s Hat. Infiltrators also attacked elements of the 23d Infantry just behind the 9th Infantry. The Chinese took heavy casualties and were forced to suspend their attack in the early morning hours, only to resume just before dawn. Vigorous U.S. counterattacks restored most of the main line positions. Attacks also were pressed against the U.S. 25th Infantry Division to the 2d Division’s left, prompting a now-alerted U.S. command to cancel the advance planned for 26 November. Suddenly on the defensive, U.S. soldiers dug in and consolidated their positions while waiting for new Chinese attacks.

Eighth Army’s situation was complicated by the fact that the Chinese broke through elements of the ROK II Corps on the army’s right wing. They penetrated the ROK front in several places, establishing roadblocks to the rear of ROK units, cutting them off and creating panic. By noon on the twenty-sixth the ROK II Corps front had folded, exposing Eighth Army’s entire flank.

Reacting quickly, Walker sent the 1st Cavalry Division, at that time guarding supply installations and routes in Eighth Army’s rear, and the Turkish Brigade, in IX Corps reserve, forward to protect possible Army lines of retreat. Farther west, Walker halted the 24th Division and prepared to conduct an active defense all along his lines. Although his intelligence officer (G–2) raised the estimate of Chinese troops in the area from 54,000 to 101,000, Walker still did not realize the size of the Chinese offensive. No one did. FEC headquarters merely reported to Washington that "a slowing down of the UN offensive may result" from these new attacks.

Late on the twenty-sixth Chinese forces struck again on the Eighth Army’s right flank, with the goal of exploiting the collapse of the ROK II Corps while attempting to flank the entire Eighth Army from the east. Attacking heavily in the east and center sections of the UN line, the Chinese threw five field armies into the fight while sending another

11

against the 24th Division to the west on a holding mission. Attacks against the ROK 1st Division drove that unit back and soon exposed the flanks of both the U.S. 24th and 25th Divisions. Only a rapid readjustment of forces plugged this gap and stabilized the situation by early evening on 27 November. However, the situation was growing grim. By mid-afternoon on the twenty-eighth all U.S. and ROK units were in retreat. Attempts by the 2d Division to hold the line and by the 1st Cavalry Division and Turkish Brigade to restore Eighth Army’s right flank were in vain. Two Chinese Armies, the 42d and 38th, were pouring through the broken ROK lines to Eighth Army’s east and threatening to envelop the entire force. Walker’s only hope was to bring off a fighting withdrawal of his army deep behind the Ch’ongch’on River line, below the gathering Chinese thrust from the east.

The withdrawal of Eighth Army units was made more difficult by the thousands of fleeing Korean refugees who blocked the roads. In addition, the hordes of refugees gave excellent cover to Chinese and North Korean infiltrators, who often dressed in Korean clothing, went through U.S. checkpoints, and then turned and opened fire on the startled Americans. The tactics repeated those used by the North Koreans during the initial invasion of the South and were often equally effective. One 7th Cavalry company commander was killed and eight of his men wounded by enemy infiltrators throwing hand grenades. As in the summer, Eighth Army orders directed that refugees be diverted from main

12

roads, escorted by South Korean police, and routed around allied defensive lines, although the strictures were often difficult to enforce.

The brunt of the renewed enemy attacks fell on the exposed U.S. 2d Infantry Division. With his division almost cut off from the rest of the Army, Maj. Gen. Laurence B. "Dutch" Keiser relied upon the Turkish Brigade to protect his right flank as he prepared to withdraw from Kunu-ri. The Chinese, however, bypassed the Turks, who remained concentrated at Kaech’on, ten miles to the west of Kunu-ri, and established roadblocks on the 2d Division’s withdrawal route to the south. These roadblocks, combined with attacks against U.S. and ROK troops north and northeast of Kunu-ri, proved a lethal combination. As the 2d Division began its withdrawal under pressure on the morning of the thirtieth, it found itself literally "running the gauntlet" as its trucks and vehicles were trapped on a congested valley road under fire from Chinese positions on the high ground to the east and west. Air strikes helped but could not dislodge the Chinese troops as they poured rifle and machine-gun fire into the slow-moving American vehicles. Soldiers were often forced to crouch in the ditches as their vehicles were raked with enemy fire; while hundreds were killed or wounded, others were forced to proceed on foot down the long road to Sunch’on, almost twenty miles to the south of Kunu-ri. Chinese roadblocks halted the columns repeatedly as the casualties mounted. Some artillery units were even forced to abandon their guns. The 37th Field Artillery Battalion, for example, lost 35 men killed, wounded, or missing and abandoned 10 howitzers, 53 vehicles, and 39 trailers. As the road became clogged with abandoned vehicles, men were forced to leave the column and make their way south as best they could. Unit integrity in some places broke down under the murderous fire. Finally, late on 30 November, the last units closed on Sunch’on and the shattered Eighth Army established a hasty defensive line from Sukch’on to the west to Sinch’ang-ni in the east, some twenty-five miles south of their initial positions on the Ch’ongch’on River line.

The battles along the Ch’ongch’on River were a major defeat for the Eighth Army and a mortal blow to the hopes of MacArthur and others for the reunification of Korea by force of arms. The 2d Division alone took almost 4,500 battle casualties from 15 to 30 November, most occurring after the twenty-fifth. It lost almost a third of its strength, along with sixty-four artillery pieces, hundreds of trucks, and nearly all its engineer equipment. While the rest of Eighth Army had not been hit as hard, with the possible exception of the ROK units whose total losses will probably never be known, there was no doubt about the magnitude of the reverse. The U.S. 1st Cavalry, 24th and 25th

13

Infantry Divisions, and the ROK 1st Infantry Division were still relatively intact, but the U.S. 2d Infantry Division, the Turkish Brigade, and the ROK 6th, 7th, and 8th Infantry Divisions were shattered units that would need extensive rest and refitting to recover combat effectiveness. Although not closely pursued by the Chinese, Walker decided that his army was in no shape to hold the Sukch’on–Sinch’ang-ni line and

14

ordered a retreat farther south before his forces could be enveloped by fresh Chinese attacks.

X Corps

The Chinese offensive of late November destroyed Eighth Army plans to push all the way to the Yalu. They also stymied the other arm of the offensive: the attack of X Corps and the ROK I Corps up the eastern coast and center of the peninsula. General Almond, following the intent of General MacArthur to push vigorously against the retreating foe, had planned a multipronged operation using these two corps. The ROK I Corps, consisting of the ROK 3d and Capital Divisions, was to proceed up the coastal roads over 200 miles northeast to Ch’ongjin and then on to the Yalu, there to guard the X Corps right flank. The X Corps was to attack north and west of the Changjin Reservoir. Its 7th Infantry Division was to occupy the center of the X Corps front and push to the Yalu at Hyesanjin, about 160 miles north of Wonsan. On the left of the corps, the 1st Marine Division was to proceed up both sides of the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir, about halfway to the border, tie in with the ROK II Corps of the Eighth Army to the west, and then push sixty more miles north towards the Yalu at Huch’angganggu and Singalp’ajin. However, despite the urgings of the X Corps commander for more speed, 1st Marine Division Commander Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith was leery about dispersing his division over too broad a front. He ordered his units to attack cautiously, maintaining unit integrity, and within generally supporting distances of each

15

other. The terrain in this part of Korea—narrow roads often cut by gullies and valleys with imposing ridgelines and mountains surrounding them—made it critical for units to stay together.

Rounding out X Corps was the newly arrived 3d Infantry Division, which landed at Wonsan between 7 and 15 November and was augmented by a ROK marine regiment. These units were to guard the corps rear, relieve the marines of any port protection duties, and prepare to conduct offensive operations in support of corps operations as needed. The 3d Division faced some challenges with making a fighting team out of its subordinate units. The 65th Infantry Regiment, filled out with hundreds of mobilized Puerto Rican National Guardsmen, had only recently been assigned to the division and had not worked with the division staff officers before. In addition, while training in Japan, the 3d Division’s 7th and 15th Regiments had been assigned thousands of minimally trained Korean augmentees, called KATUSAs (Korean Augmentees to the U.S. Army). Nonetheless, the division was fresh and constituted the major reserve available to X Corps.

In a seemingly minor change in plans, Almond ordered the 31st Regimental Combat Team (RCT) of the 7th Division to relieve the 5th Marine Regiment on the east side of the Chosin Reservoir so the marines could concentrate their forces on the west, reorienting their drive to the north and west of the frozen reservoir. The 31st RCT, like most of the rest of the 7th Infantry Division, was widely scattered and arrived in its new area in bits and pieces. The roads were treacherous, trucks were in short supply, and the different battalions and artillery assets only slowly began to assemble east of the reservoir. Although the unit was called the 31st RCT, the 31st regimental commander, Col. Allan D. "Mac" MacLean, was to command the 1st Battalion of the 32d Infantry along with his 2d and 3d Battalions of the 31st Infantry.

The 1st Battalion, 32d Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Donald C. Faith, Jr., was first to reach the new positions, relieving the marines on 25 November. Faith’s battalion was alone on the east side of the reservoir for a full day before other elements of Task Force (TF) MacLean—the 3d of the 31st Infantry and two artillery batteries—arrived on the twenty-seventh. The 2d Battalion, 31st Infantry, the other artillery battery, and the 31st Tank Company were still missing. The tanks were on the road just outside the Marine perimeter at Hagaru-ri at the southern end of the reservoir, and the 2d of the 31st was still en route. Nevertheless, MacLean confidently prepared to launch his attack the next day.

Almond’s offensive was not to be. Late on 27 November the Chinese struck the U.S. forces on both sides of the Chosin Reservoir

16

nearly simultaneously. Two CCF Divisions, the 79th and 89th, attacked the marines west of the reservoir in the Yudam-ni area. The marines killed the Chinese by the hundreds but were in danger of being cut off from the division headquarters at Hagaru-ri, at the southern end of the reservoir. In a similar maneuver, the CCF 80th Division struck the spread-out positions of Task Force MacLean while simultaneously moving around its flank to cut it off from the marines at Hagaru-ri. Initially successful, the Chinese were finally stopped just before dawn.

During the day on 28 November, General Almond and his aide, 1st Lt. Alexander Haig, helicoptered into the perimeter of TF MacLean. Despite all the evidence of massive Chinese intervention, Almond exhorted the soldiers to begin the offensive. "We’re still attacking," he told the soldiers, "and we’re going all the way to the Yalu." The corps

17

commander then flew back to Hagaru-ri, convinced that TF MacLean was strong enough to begin its attack and deal with whatever "remnants" of CCF forces were in their way.

That evening the Chinese remnants struck again. The CCF 80th Division hit the dispersed U.S. units with waves of infantry. Despite the reassuring presence of tracked antiaircraft weapons (40-mm. killing machines), the sub-zero cold and the constant Chinese attacks began to take their toll. The fighting was often hand to hand. Convinced now that launching any kind of attack on the twenty-ninth was futile, Colonel MacLean abruptly ordered a pullback to form a more consolidated defense. That accomplished, he proposed waiting for the arrival of his missing third battalion before resuming any offensive operations. However, during the withdrawal operations his troops came under renewed enemy attack, and in the confusion MacLean was captured by the Chinese. With no hope of rescuing his commander, Colonel Faith took command of the task force. Colonel MacLean in fact died of wounds four days after his capture.

The epic struggle of Task Force MacLean—now called Task Force Faith—was drawing to a close. Its separated tank company, augmented by a pickup force of headquarters company soldiers and clerks, attempted twice to relieve the beleaguered force. However, the tanks foundered on the icy roads, and the attacks were further hindered by misdirected air strikes. The tanks withdrew into the safety of Hagaru-ri. Faith, unaware of this attempted rescue because of faulty communications, was running short of ammunition and had over four hundred wounded on his hands. General Smith, commander of the 1st Marine Division, was given operational control of the cut-off Army unit, but apparently had his hands full withdrawing his marines in an orderly fashion into Hagaru-ri. The 7th Division commander, Maj. Gen. David G. Barr, flew into the perimeter of TF Faith on the thirtieth, but had only bad news for Colonel Faith. The Marines could provide little more than air support. Continued Chinese attacks during the night of the thirtieth and into the morning of 1 December left TF Faith in a dangerous situation with no help in sight. Chinese assaults had almost destroyed the perimeter that night, and the number of wounded went up to nearly six hundred, virtually one-fourth of the entire formation. Believing that one more Chinese attack would destroy his force, Faith decided to withdraw and run the Chinese gauntlet down the frozen road along the east side of the reservoir in hopes of reaching the marines at Hagaru-ri.

On the morning of 1 December the exhausted men of TF Faith formed into a column with the wounded piled into about thirty overcrowded trucks. Taking a while to get organized, the column began

18

to pull out in the early afternoon just as their Marine air cover arrived. Tragically, the lead plane dropped its napalm short, and the thick, jellied gasoline exploded near the head of the column, badly burning over a dozen soldiers. Many of the men ran for cover, destroying what little order the column had left. Colonel Faith rallied the men and got them moving again, but near-panic had set in and the men began to gather in leaderless groups. The CCF, noting the withdrawal, began to pour in fire from the high ground to the east of the column. As it advanced, the column encountered a destroyed bridge on the road. Bypassing the bridge was possible, but only one vehicle at a time could be winched up the steep slope on the other side. The CCF clustered along the column, directing fire into the exposed trucks.

Farther south, the column was stopped by a Chinese roadblock near Hill 1221. Some brave soldiers under the command of a few officers stormed up the slopes and, despite severe casualties, managed to take most of the hill, gaining valuable time for the column. It was getting dark, and the lights of Hagaru-ri could be seen in the distance over the ice-covered reservoir. However, the Chinese roadblock stood between the column and safety. Desperately, Colonel Faith gathered a few men and charged the Chinese defenses. Seizing the position, the American soldiers managed to disperse the enemy, but Faith was mortally wounded. Although his men managed to prop him up on the hood of his jeep and the convoy began moving again, the retreating force began to give up hope. Despite the desperate attempts of the few remaining leaders, the convoy began to come apart. Just miles from safety, the column hit another blown bridge. The few unwounded men began moving out over the ice, thick enough for foot travel but not for vehicles, leaving the stranded convoy behind. By dark Task Force Faith thus ceased to exist. As the CCF fire intensified with heavy machine guns and grenades, the remaining able soldiers abandoned their trucks and fled to Hagaru-ri over the ice. Colonel Faith, later awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously, remained behind with his men to die in the cold.

All during the night of 1–2 December, shattered remnant of Task Force Faith trickled into the Marine positions at Hagaru-ri. A few were rescued by Marine jeeps racing out over the ice to pick up dazed, frostbitten survivors. Some 319 Americans were rescued in this manner by individual marines. Many of the worst wounded were airlifted to safety. Of the 2,500 men of Task Force Faith, 1,000 were killed, wounded, captured, or left to die of wounds. After the air evacuation, about 500 7th Infantry Division soldiers were left to accompany the 1st Marine Division as it began its withdrawal from Hagaru-ri to the port of Hungnam, fifty miles southeast, and evacuation by sea.

19

The men of Task Force Faith did not die in vain. They had virtually destroyed an entire Chinese division and prevented any possible attack south by the Chinese for four critical days. If they had not been able to hold out as long as they had, the 80th Division might have hit the 1st Marine Division perimeter at Hagaru-ri in force before the 5th and 7th Marines could have withdrawn. Those units might then have faced dug-in Chinese roadblocks in their rear instead of a safe perimeter and a reasonably open road to the south. The entire fate of X Corps may well have been different, if not for the bravery and stubborn defense of the area east of the Chosin Reservoir by the men of Task Force Faith.

Faced with the renewed Chinese attacks on X Corps and Eighth Army, General MacArthur finally admitted that the Chinese intervention had changed everything, announcing, "We face an entirely new war." Summoning both Walker and Almond to Japan even as their units were fighting off the massive Chinese attacks, MacArthur grappled with ideas to save his units. He considered establishing a defensive line, or perhaps two enclaves along the coast, to prevent the destruction of Eighth Army and X Corps and the loss of all that had been gained since September. Another plan had the 3d Infantry Division attacking directly east from Wonsan into the Chinese flank, but the units involved considered it far too risky and besides, the terrain made it nearly impossible. MacArthur next asked Washington for augmentation by troops of Chiang Kai-shek, the defeated ruler of China now in exile with some of his army on the island of Taiwan. Viewing this scheme as a dangerous escalation of the war, Washington would have nothing to do with it. Sensing disaster, MacArthur began imagining the total destruction of his forces in Korea or an evacuation of the mainland.

Retreat from North Korea

After the defeat at the Ch’ongch’on River, General Walker realized that it was necessary to withdraw his Eighth Army from its positions before the Chinese could move around its still-open right flank. He ordered an immediate retreat to create an enclave around P’yongyang. However, even as troops occupied their new positions, he realized that he lacked the forces to maintain a cohesive defensive line. Three of his ROK divisions (6th, 7th, and 8th Infantry Divisions) had disintegrated; the U.S. 2d Infantry Division was in shambles; and all the other units had taken heavy loses in men, materiel, and morale. Faced with these problems, Walker decided to abandon P’yongyang. He needed time to regroup and refit his units. He ordered the with-

20

U.S. combat engineers place satchel charges on a railroad bridge near P'yongyang,

preparing to destroy it to slow the Communist advance. (DA photograph)

drawal of the army to a line along the Imjin River, about ninety-five miles to the south near the prewar border. He further ordered that all supplies that could not be moved or any installations that could be of use to the enemy be destroyed.

Moving slowly down the few good roads in Korea, Eighth Army units began pulling back from their positions near P’yongyang on 2 December and retreated over the course of three weeks to a line along the Imjin River, from Munsan-ni on the western coast to just south of the Hwach’on Reservoir across the peninsula. Caught wrong-footed by

21

U.S. soldiers retreat from P'yongyang in December 1950, carrying their equipment

on traditional Korean "A" frames. (DA photograph)

this quick withdrawal, and needing time of their own to refit and resupply their troops, the Chinese did not immediately pursue. By 23 December the U.S. I and IX Corps and the ROK III and II Corps, west to east, were in place along the line. The ROK I Corps began to arrive after its evacuation from northeast Korea, to be placed on the far right of the line, anchoring the line to the eastern coast. It was not a strong defensive position, but it had the advantage of leaving no flanks in the air. It also maintained UN control of Seoul.

In northeast Korea, with the consolidation of the 1st Marine Division at Hagaru-ri along with the remnants of TF Faith, the situation in the X Corps area was improved, but hardly reassuring. There was only one narrow road leading from Hagaru-ri to the port of Hungnam, over fifty tough miles to the southeast. At Hungnam, Almond planned to establish a perimeter and begin the slow process of withdrawal. Early in the process he had ruled out a "Dunkirk" situation, where the men would be extracted while leaving their equipment and supplies behind. Such a blow to allied pride and troop morale was

22

too grievous to contemplate. The challenge was first to safely withdraw the Marine and Army units from the Chosin Reservoir area down to Hungnam, then to establish a strong defensive perimeter, and finally to begin shrinking that perimeter under enemy pressure while loading up all the supplies and equipment possible. It would be a race between the Chinese forces and U.S. tactical and logistical skills.

The first challenge—withdrawing the Marine and Army units from Hagaru-ri to Hungnam intact—was potentially the most dangerous. If

23

the Chinese in the area could cut the road between Hagaru-ri and Hungnam with a strong enough force, the entire 1st Marine Division could be lost. Such a disaster would seriously undercut the entire UN position in Korea. The effect on the American public would be tremendous. Their failure to rescue TF MacLean/Faith, fresh in their minds, the Marine and X Corps staffs began working together to coordinate their movements and fires to prevent any chance of a reoccurrence of such a tragedy. Their planning, coupled with massive American firepower and airpower and the sheer persistence and courage of the marines and soldiers at hand, would turn the tide and snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

The 1st Marine Division plan was relatively clear and straightforward, although still difficult to execute. The division with its attached Army units would move all its men and equipment down the road to Hungnam, while combat units would systematically take and clear the ridgelines dominating the road. There was to be no repetition of the Kunu-ri gauntlet of the 2d Infantry Division. Combat power would clear the ridges, while air support and artillery would destroy any roadblocks or major concentrations of Chinese forces. Meanwhile, X Corps would send a special task force from the relatively fresh 3d Infantry Division—code-named Task Force Dog—about thirty miles north up the road from Hungnam through Hamhung to just south of the Funchilin Pass near Kot’o-ri. Task Force Dog, with its powerful attached artillery units, would keep the road south of the pass open all the way to the port.

Leading the way south some eight miles to Kot’o-ri on 6 December were the 7th Marines and the ad hoc Army battalion formed from the remnants of Task Force Faith/MacLean. With artillery support carefully planned and around-the-clock air cover, the force quickly met and overcame enemy resistance at various strong points. The rest followed, and a Marine rear guard was out of Hagaru-ri by midmorning of the following day. During the fight south to Kot’o-ri, some 103 marines lost their lives, with almost 500 wounded.

Once at Kot’o-ri, the Marine and Army force faced a major obstacle: a sixteen-foot gap in the road near the Funchilin Pass. A steep chasm prevented any hope of bypassing the gap. The staff of X Corps coordinated an airdrop on 7 December of eight 2 1/4-ton treadway bridge sections to cross the gap. In a series of air operations, all eight sections were dropped by parachute near the pass, with one falling inside Chinese lines and another damaged in the drop. However, the remaining sections bridged the gap and, despite some tense moments when trucks almost slid off the narrow bridge, the way was clear.

24

A U.S. infantryman with a 75-mm recoilless rifle (rocket launcher) guards

a pass south of the Chosin Reservoir. (DA photograph)

Followed by hundreds of fleeing Korean refugees, the Marine and Army forces made their way south against continuing Chinese flank attacks. Finally, early in the morning of 10 December, the first linkup occurred between the lead elements of the northern force and Task Force Dog. Over the next two days the rest of the Marine and Army elements withdrew through the covering elements of TF Dog to safety in Hungnam. Again, the withdrawal came at a price. The Chinese managed to cut the road near Sudong, about ten miles south of Kot’o-ri, late on 10 December, but a composite Marine force led by two Army officers beat back the enemy. In the process one of the leaders of the force, Army Lt. Col. John U. D. Page, was killed in action and later received the Medal of Honor posthumously. Despite the attacks of two Chinese armies, the withdrawal from the Chosin area of over eleven thousand Marines and one thousand soldiers was successful.

On 8 December MacArthur ordered X Corps to evacuate through the port of Hungnam and redeploy to South Korea as part of Eighth Army. Given the size of the force and the near presence of the Chinese, the withdrawal had to be a carefully orchestrated event. Setting up a special Evacuation Control Group, Almond directed the

25

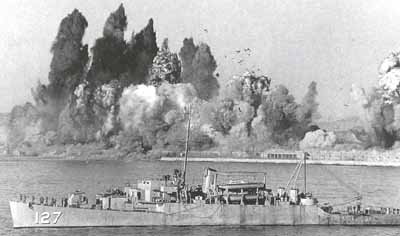

The USS Begor lies off the port of Hungnam as demolition charges destroy

the dock facilities on 24 December 1950. (U.S. Navy photograph)

battle-weary 1st Marine Division to be evacuated first, from 9–15 December. It was followed by the ROK I Corps from 15–17 December, the 7th Infantry Division from 18–21 December, and the 3d Infantry Division from 21–24 December. All this occurred while coordinating shipping with the Navy’s Task Force 90, uploading thousands of tons of supplies, and maintaining a secure perimeter.

The withdrawal from Hungnam was accomplished successfully, despite all the potential dangers. The X Corps arranged for the withdrawal of over 105,000 troops; 18,422 vehicles; 350,000 tons of bulk cargo; and as a bonus some 98,100 refugees. Naval gunfire support assisted in pulling off the maneuver with minimal enemy interference. The Navy and Army worked together as well to coordinate a massive demolitions plan to destroy any cargo too bulky or dangerous (like frozen dynamite) to move, along with the docks and port facilities. The X Corps outloaded all its elements on a strict timetable and moved them by sea to Ulsan, just north of Pusan in South Korea, for refitting and redeployment to the front to help Eighth Army hold the line. The last soldiers from the 3d Infantry Division embarked on their landing craft to the waiting ships on Christmas Eve 1950. As they left,

26

the docks erupted behind them in a series of huge explosions. The attempt to reunify Korea by force was over.

Ridgway Takes Command

General Walker was an indirect casualty of the Chinese attacks. On the morning of 23 December, with the redeployment of Eighth Army to new lines in the south complete and the first elements of the evacuated X Corps on the way, the Eighth Army commander left Seoul by jeep on an inspection trip. Ten miles north of the capital, his vehicle zoomed north past several U.S. trucks halted on the opposite side of the road. Suddenly, a Korean truck driver pulled out of his lane, heading south, and tried to bypass the trucks. In doing so, he pulled into the northbound lane and collided with Walker’s jeep. The commander was knocked unconscious and later pronounced dead from multiple head injuries.

The man selected to replace General Walker as Eighth Army commander was Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway. At the time Ridgway was serving on the Army staff in the Pentagon as deputy chief of staff for operations and administration. A famed airborne commander from World War II, Ridgway was knowledgeable about conditions in Korea and the Far East and had a strong and dynamic personality. He would need both for the task ahead. His success in turning Eighth Army’s morale around, using little more than a magnetic personality and bold leadership, is still a model for the Army, showing how the power of leadership can dramatically change a situation.

Ridgway landed in Tokyo on Christmas Day 1950 to discuss the situation with MacArthur. The latter assured the new commander of his full support to direct Eighth Army operations as he saw fit. Ridgway was encouraged to retire to successive defensive positions, as currently under way, and hold Seoul as long as he could, but not if it meant that Eighth Army would be isolated in an enclave around the city. In a foreshadowing of his aggressive nature, Ridgway asked specifically that if he found the combat situation "to my liking" whether MacArthur would have any objection to "my attacking"? MacArthur answered, "Eighth Army is yours, Matt. Do what you think best."

General Ridgway knew that one of his first jobs was to restore the Eighth Army soldiers’ confidence in themselves. To accomplish this he had to be aggressive, despite the hard knocks of November and December, and find other leaders in Eighth Army who were not defeatist or defensive oriented. In practice he proved quick to reward commanders who shared his sentiments and just as quick to relieve those officers at any level who did not. During one of his first brief-

27

ings in Korea at I Corps, Ridgway sat through an extensive discussion of various defensive plans and contingencies. At the end he asked the startled staff where their attack plans were. The corps G–3 (operations officer) responded that he had no such plans. Within days I Corps had a new operations officer. The message went out: Ridgway was interested in taking the offensive. To aid in this perception he also established a plan to rotate out those division commanders who had been in action for six difficult months and replace them with fresh leaders who would be more interested in attack and less in retreat. In addition, he sent out guidance to commanders at all levels to spend more time at the front lines and less in their command posts in the rear. The men had to see their commanders if they were to have confidence that they had not been forgotten. All these positive leadership steps would have a dramatic effect almost from the first. Eighth Army was in Korea to stay.

Ridgway, despite his aggressive intent, was also enough of a realist to know that the Chinese were still capable of launching major attacks. He also knew that his Eighth Army still needed time to refit and reorganize. Thus, he immediately began planning to strengthen the defensive lines around Seoul while bringing up X Corps as quickly as possible to strengthen the Wonju sector in the center of the line. Almond’s X Corps was no longer independent, but would be just another corps of the Eighth Army, tied into a new defensive line that stretched unbroken from one side of the peninsula to the other.

Before Ridgway’s changes could be instituted, however, the Chinese attacked again. Beginning on 26 December, the CCF struck hard at UN units on the western approaches to Seoul. Supporting attacks occurred as well in the central and eastern parts of the line. The Chinese hit the ROK units hard, and again several units broke. Two out of three regiments of the ROK 2d Division fled the battlefield, leaving their valiant 17th Regiment to fight alone and hold its position for hours despite heavy losses. Ridgway reluctantly ordered a general, but orderly, withdrawal, with units instructed to maintain contact with the enemy during their retreat, rather than simply giving up real estate without inflicting losses on the enemy.

Initially, Eighth Army pulled back thirty miles to a defensive line along the Han River to protect Seoul. By 2 January both I and IX Corps had successfully concluded the new withdrawal and, with extensive firepower at their command, their chances of holding the city were good. However, there was a distinct danger that the two corps could be outflanked to the east and forced to defend Seoul with their backs to the sea. Ridgway, unwilling to risk the loss or isolation of so much of

28

his combat power, reluctantly ordered the retreat of both corps to "Line C," just south of the Han. For the third time in the war so far, Seoul was to change hands.

Followed by hordes of refugees hauling their loved ones or a few personal treasures on their backs or on oxcarts, I and IX Corps began withdrawing from Seoul on 3 January. The loss of the capital was again a bitter pill for everyone to swallow. The cold froze refugee and soldier alike as the long UN columns snaked southward again. As the Han River began to freeze solid, refugees braved the treacherous ice to reach the temporary safety of UN lines. However, the freezing of the river threatened the entire UN position, since the same ice that held refugees could hold Chinese infantry intent on heading off the American withdrawal. Before such attacks could occur, however, the movement south was completed.

On the whole, the allies accomplished the evacuation of Seoul with minimal casualties. However, one of the units, the attached 27th Commonwealth Brigade, had been forced into hand-to-hand combat to rescue one of its cut-off battalions and had suffered heavy casualties. Finally, on the morning of 4 January, despite the continuing stream of desperate refugees, Eighth Army engineers blew the three ponton bridges and the main railway bridge over the Han to prevent their use by the pursuing Chinese. The withdrawal to Line C was complete. However, even as units were moving into position on this defensive line, plans were being executed to withdraw some thirty-five miles farther south to Line D, running from P’yongt’aek in the west, northwestward through Wonju to Wonpo-ri.

The freezing of the Han River limited the defensive capabilities of UN troops scattered along Line C. In addition, the ROK III Corps in central Korea had virtually collapsed. Only the ROK 7th Division was in a position to help stabilize the line. The ROK 2d Division was down to less than a regiment. The ROK 5th and 8th Divisions were in complete retreat toward Wonju. To the east the ROK II Corps’ 3d Division was also withdrawing to the south. As a result Ridgway ordered the U.S. X Corps, still recovering from its near-disaster in northeast Korea, to move up and take responsibility for some thirty-five miles in the center of Line C. Almond was to have control of the U.S. 2d and 7th Infantry Divisions and whatever remnants that he could gather of the ROK 2d, 5th, and 8th Divisions. To the right of X Corps, the ROK III and I Corps would extend Line C to the eastern coast. However, the staying power of this new defensive line was problematic.

Ridgway assessed the situation and, after the withdrawal from Seoul was completed, ordered the entire Eighth Army to withdraw

29

again to Line D, which was somewhat redrawn to run straight east from Wonju to Samch’ok instead of northeastward to Wonpo-ri. Beginning on 5 January all five corps of Eighth Army pulled back to this line. Despite its losses, the Eighth Army situation was thus much improved from the last days of November, with better coordination between units and fewer open flanks.

30

The enemy attacks, however, were not over. The rejuvenated NKPA opened a two-corps assault on X Corps positions near Wonju in the center of Line D on 7 January. The NKPA V Corps hit the 2d Division at Wonju with two divisions in a frontal attack, while a third division attacked from the northwest against the adjacent ROK 8th Division. They were assisted by one of the divisions of the NKPA II Corps, which also launched attacks against the neighboring ROK III Corps to the east. The North Koreans managed to force the 2d Division out of Wonju by the evening of 7 January, and all counterattacks failed to retake the city.

The North Korean success at Wonju and the dangerous penetration of the ROK III Corps by the NKPA II Corps threatened to unhinge the entire UN line. However, the harsh winter weather and logistical challenges, coupled with newly aggressive patrolling by UN soldiers, began to take their toll on the attackers’ momentum. The defensive line was reestablished just south of Wonju, cutting off the weakened NKPA divisions that had penetrated the line. The 1st Marine Division was sent up from reserve to conduct a systematic antiguerrilla campaign against the scattered forces and in three weeks managed to destroy virtually one entire NKPA division. By the end of January a new defensive line had been established from the Han River, running just south of Wonju to Samch’ok on the eastern coast.

While X Corps was dealing with the potentially disastrous penetration in the center, I and IX Corps were busy stabilizing their positions

31

U.S. military leaders in Korea visit the front linres north of Suwon on 28

January 1951. General MacArthur is at the right front. General Ridgeway is in

the center, third from the left. (DA photograph)

and instituting a series of aggressive reconnaissance-in-force patrols to their front. General Ridgway, dismayed by the continuing poor showing of his battle-weary units, demanded that unit commanders lead the way in restoring an aggressive spirit. To help rebuild the still shaky morale of Eighth Army, he ordered I Corps to plan a major reconnaissance-in-force in its sector to test the measure of Chinese resistance. Operation Wolfhound used troops from the U.S. 25th Infantry Division (especially the 27th Infantry Regiment, the "Wolfhounds," from which the operation drew its name), the U.S. 3d Infantry Division, and the ROK 1st Division. Maj. Gen. Frank W. "Shrimp" Milburn, commander of I Corps, directed it along the Osan-Suwon axis, twelve to twenty miles to the north, supported by artillery and tanks.

The reconnaissance began on 15 January. The 3d Infantry Division units involved were quickly immobilized by enemy defensive positions, but the rest of the forces met little opposition until near Suwon. There, Chinese troops forced the Wolfhound units to turn back just south of their objective, but they were able to establish an advance corps outpost line along the Chinwi River, south of Osan, by

32

late on 16 January, while inflicting some 1,380 enemy casualties at the cost of 3 killed and 7 wounded of their own. More important, they had showed both the Chinese and themselves that the Eighth Army continued to have an offensive spirit.

Almost immediately, two other reconnaissances-in-force sallied out from UN lines: another from I Corps and a one-day action in the IX Corps sector, both on 22 January. The reconnaissance in the IX Corps sector consisted of a tank-heavy formation called Task Force Johnson after its commander, Colonel Johnson. The immediate results of both operations were small, but the ground was being laid for a return to the offensive by the entire Eighth Army in the near future.

Analysis

The period from early November 1950 to late January 1951 was in many ways the most heartbreaking of the Korean War. During the previous summer the North Korean attack had been a total surprise, and the disastrous retreat to the Pusan Perimeter was painful in the extreme. However, the series of defeats could be explained by the necessarily haphazard and slow reinforcement of the outnumbered U.S. and South Korean forces. Moreover, these defeats were followed by elation as the Inch’on landings reversed the situation and the UN forces seemed on the verge not just of victory in South Korea but of total victory, including the liberation of North Korea and the reunification of the peninsula. All these dreams were swept away by the massive intervention of the Chinese Army in late November 1950. There would be no homecoming victory parade by Christmas.

The initial warning attacks and diplomatic hints by the Chinese were ignored by the overconfident Far Eastern Command under General MacArthur. MacArthur’s failure to comprehend the reality of the situation led the entire United Nations army to near disaster at the Ch’ongch’on River and the Chosin Reservoir. Only the grit and determination of the individual American soldiers and marines as they fought the three major enemies of cold, fear, and isolation held the UN line together during the retreats from North Korea. Once tied together into a coherent defensive line, under new and dynamic leadership, these same soldiers and marines showed their determination to continue the fight. Hard battles lay ahead, but the period of headlong retreats from an attacking, unsuspected foe, was finally over.

33

Further Readings

Appleman, Roy E. East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987.

———. Escaping the Trap: The U.S. Army X Corps in Northeast Korea, 1950. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1990.

———. South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June–November 1950). U.S. Army in Korea. Washington, U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1961.

Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea 1950–53. New York: Doubleday, 1987.

Marshall, S. L. A. The River and the Gauntlet: November 1950, the Defeat of Eighth Army. Nashville, Tenn.: Battery Press, 1987.

Mossman, Billy C. Ebb and Flow: November 1950–July 1951. U.S. Army in Korea. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1990.

Stanton, Shelby. America’s Tenth Legion: X Corps in Korea, 1950. Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1989.

35

CMH Pub 19-8

Cover: U.S. 7th Infantry Division Soldiers pass through the outskirts of Hyesanjin in November 1950. (DA photograph)

|

Last updated 3 October 2003

|