CHAPTER IV

VII Corps Penetrates the Line

Having engineered the authorization to reconnoiter the West Wall in force on 12 September, General Collins of the VII Corps expected to accomplish more by the maneuver than did General Gerow of the V Corps. General Collins had in mind a strong surprise attack which might breach the fortified line in one blow before the Germans could man it adequately. Even if he had to pause later for resupply, the West Wall would be behind him.

Though oriented generally toward the region known as the Aachen Gap, the VII Corps operated in a zone about thirty-five miles wide that encompassed only a narrow portion of the gap. This portion was the Stolberg Corridor, southeast and east of Aachen. The rest of the zone was denied by dense pine forests in sharply compartmented terrain. Stretching northeast from Verviers, Belgium, for about 30 miles almost to Dueren on the Roer River, the forest barrier averages 6 to 10 miles in width. (See Map III.) Within Belgium, it embraces the Hertogenwald; within Germany, the Roetgen, Wenau, and Huertgen Forests. Only one logical route for military advance runs through the forests, a semblance of a corridor extending from the German border near Monschau northeast across a village-studded plateau toward the Roer at Dueren. For convenience, this route may be called the Monschau Corridor.

It was obvious that the main effort of the VII Corps should be made in the north of the zone through the more open Stolberg Corridor. Yet even this route had some disadvantages. At one point it is less than six miles wide. At others it is obstructed by the sharp valleys of the Inde and Vicht Rivers and by a congested industrial district centering on Stolberg and the nearby town of Eschweiler.

General Collins entrusted the reconnaissance in force on 12 September to two combat commands of the 3d Armored Division and two regiments of the 1st Division. Each of the infantry regiments was to employ no more than a battalion at first. The infantry was to reconnoiter in the direction of Aachen, while the armor was to strike the face of the Stolberg Corridor. Should the West Wall be easily breached, the 1st Division was to capture Aachen, the 3d Armored Division was to push up the corridor to Eschweiler and thence to Dueren, and the 9th Division was to operate on the right wing to sweep the great forest barrier.1

In the event, the reconnaissance on 12 September failed to accomplish what General Collins had hoped for. Not through any great German strength did it fail, but because roadblocks, difficult terrain, and

[66]

Still intent on pressing forward without delay, General Collins nevertheless interpreted the results of the reconnaissance as an indication that farther advance might not be gained merely by putting in an appearance. In these circumstances, capturing the city of Aachen at this stage would serve no real purpose. The open left flank of the VII Corps might be secured by seizing high ground overlooking Aachen rather than by occupying the city itself.2 The decisive objective was the second or main band of West Wall fortifications which ran east and southeast of Aachen.

Reflecting this interpretation, General Collins told the 1st Division to avoid the urban snare of Aachen and protect the left flank of the corps by seizing the high ground east of the city. When the XIX Corps came abreast on the north, Aachen then could be encircled. The 3d Armored

GENERAL COLLINS

Division was to proceed as before to penetrate both bands of the West Wall, capture Eschweiler, and turn east toward the Roer River; the 9th Division was to protect the right flank of the armor by penetrating the great forest barrier to seize road centers in the vicinity of Dueren. Though General Collins was not officially to label his advance an "attack" for another twenty-four hours, he was actually to launch a full-scale attack on 13 Septem-

[67]

ber under the guise of continuing the reconnaissance in force.3

General Collins specified further that advance was to be limited for the moment to the west bank of the Roer River, a stipulation probably based upon the physical and logistical condition of the VII Corps. The troops, their equipment, and their vehicles had been taxed severely by the long drive across France and Belgium. Little more than a third of the 3d Armored Division's authorized medium tanks were in operational condition. Shortages in ammunition, particularly in 105-mm. ammunition, necessitated strict rationing. The divisions often had to send their own precious transportation far to the rear in search of army supply dumps that had fallen behind. Trucks of the 1st Division made two round trips of 700 miles each.4

For all these problems and more, the temptation to breach the West Wall before pausing was compelling. Even if the Germans had been able to man the line, there was some chance that they intended to fight no more than a delaying action within the fortifications, reserving the main battle for the Rhine River. "Militarily," the VII Corps G-2, Col. Leslie D. Carter, noted, "[the Rhine] affords the best line of defense." Yet, Colonel Carter conceded, "for political reasons, it is believed that the West Wall will be held in varying degrees of effectiveness."5 Perhaps the most accurate indication of what the VII Corps expected came from the G-2 of the 9th Division. Vacillating for a while between two theories, the 9th Division G-2 finally merged them in a prediction that the enemy intended to hold the West Wall but that he probably was capable only of delaying action.6

The first of the two bands of the West Wall facing the VII Corps was a thin single line closely following the border west and south of Aachen. This band the Germans called the Scharnhorst Line. About five miles behind the first, the second band was considerably thicker, particularly in the Stolberg Corridor. Called the Schill Line, the second band became thinner in the Wenau and Huertgen Forests before merging with the forward band at the north end of the Schnee Eifel. Dragon's teeth marked the West Wall in the Aachen sector along the forward band west of Aachen and across the faces of the Stolberg and Monschau Corridors.

Colonel Carter, the VII Corps G-2, expected the Germans to try to hold the two bands of the West Wall with the battered remnants of two divisions and a haphazard battle group composed primarily of survivors of the 105th Panzer Brigade and the 116th Panzer Division. All together, he predicted, these units could muster only some 7,000 men. Elements of two SS panzer corps, totaling no more than 18,000 men and 150 tanks, might be in reserve, while some or all of two panzer brigades and four infantry divisions—all makeshift units—might be brought from deep inside Germany. "However," the G-2 added, "transportation difficulties will add to the uncertainty of these units making their appearance along the VII Corps front."7

[68]

GENERAL BRANDENBERGER

The German commander charged directly with defending the Aachen sector was the same who bore responsibility for the Eifel, the Seventh Army's General Brandenberger. Not the Eifel but Aachen, General Brandenberger recognized, would be the main point of American concentration. Yet he had little more strength there than in the Eifel.

As was the ISS Panzer Corps for a time, the other two of General Brandenberger's three corps were trying to hold in front of the West Wall while workers whipped the fortifications into shape. On the north wing, sharing a common boundary with the First Parachute Army at a point approximately six miles northwest of Aachen, was the LXXXI Corps commanded by Generalleutnant Friedrich August Schack. General Schack's zone of responsibility extended south to Roetgen and a boundary with the LXXIV Corps under General der Infanterie Erich Straube. General Straube's responsibility ran to the Schnee Eifel and a common boundary with General Keppler's I SS Panzer Corps near the Kyll River.8

Probably weakest of the Seventh Army's three corps, Straube's LXXIV Corps was to be spared wholesale participation in the early West Wall fighting because of the direction of the U.S. thrusts. General Schack's LXXXI Corps was destined to fight the really decisive action.

General Schack had to base his hopes of blocking the Aachen Gap upon four badly mauled divisions. Northwest of Aachen, two of these were so occupied for the moment with the approach of the XIX U.S. Corps that neither was to figure until much later in the fight against the VII U.S. Corps. At Aachen itself General Schack had what was left of the 116th Panzer Division, a unit whose panzer regiment had ceased to exist and whose two panzer grenadier regiments were woefully depleted. The fourth unit was the 9th Panzer Division, earmarked to defend the face of the Stolberg Corridor.

The 9th Panzer Division had been reorganizing in a rear assembly area when Field Marshal von Rundstedt had seized upon it as the only sizable reserve available on the entire Western Front for commitment at Aachen. Though traveling under urgent orders, only a company of engineers, three companies of panzer grenadiers, and two batteries of artillery had arrived at Aachen by 11 September. Desperate for some force to hold outside

[69]

Nominally, General Schack had a fifth unit, the 353d Infantry Division, but about all that was left of it was the division headquarters. Schack assigned it a sector in the Schill Line, the second band of the West Wall, and put under it a conglomeration of five Landesschuetzen (local security) and Luftwaffe fortress battalions and an infantry replacement training regiment.10

The LXXXI Corps had in addition a few headquarters supporting units, of which some were as much a hindrance as a help. Overeager demolition engineers of one of these units in rear of the 116th Panzer Division had destroyed bridges on 11 and 12 September before the panzer division had withdrawn. A battery of Luftwaffe antiaircraft artillery in position near Roetgen panicked upon hearing a rumor that the Americans were approaching. Abandoning their three 20-mm. guns, the men fled.11

To General Schack's misfortune, he anticipated the VII Corps main effort against Aachen itself. Shoring up the 116th Panzer Division at Aachen with three Luftwaffe fortress battalions and a few other miscellaneous units, he gave command of the city to the division commander, Generalleutnant Gerhard Graf von Schwerin. His limited corps artillery he put under direct control of Schwerin's artillery officer. For defense of the Stolberg Corridor, he subordinated all miscellaneous units between Aachen and Roetgen to the 9th Panzer Division.12

Other than this General Schack could not do except to wish Godspeed for promised reinforcements. Most likely of these to arrive momentarily was the 394th Assault Gun Brigade, which had six or seven assault guns. A firmer hope lay further in the future. During 12 September, Schack had learned that the first of three full-strength divisions scheduled

[70]

Though hope existed, an observer in Aachen the night of 12 September could not have discerned it. Aachen that night was Richmond with Grant in Petersburg. While General von Schwerin was regrouping his 116th Panzer Division north of the city before moving into battle, only local defense forces remained between the Americans and the city itself. Through the peculiar intelligence network war-torn civilians appear to possess, this knowledge had penetrated to a civilian population already in a quandary over a Hitler order to evacuate the city. Entering Aachen, Schwerin found the population "in panic."14

Aware that the 116th Panzer Division could not fight until regrouped and that local defense forces were no match for their opponents, Schwerin was convinced that the fall of the city was only hours away. This, the German commander thought privately, was the best solution for the old city. If Aachen was to be spared the scars of battle, why continue with the civilian evacuation? Schwerin decided to call it off. Though he may not have known that Hitler himself had ordered Nazi officials to evacuate the city, he must have recognized the gravity of his decision. He nevertheless sent his officers to the police to countermand the evacuation order, only to have the officers return with the shocking news that not only the police but all government and Nazi party officials had fled. Not one police station was occupied.15

Not to be sidetracked by this development, General von Schwerin sent his officers into the streets to halt the evacuation themselves. By daylight of 13 September the city was almost calm again.

In the meantime, Schwerin searched through empty public buildings until at last he came upon one man still at his post, an official of the telephone service. To him Schwerin entrusted a letter, written in English, for transmission to the American commander whose forces should occupy Aachen:16

I stopped the absurd evacuation of this town; therefore, I am responsible for the fate of its inhabitants and I ask you, in the case of an occupation by your troops, to take care of the unfortunate population in a humane way. I am the last German Commanding Officer in the sector of Aachen.

[signed] Schwerin.

Unfortunately for Schwerin, General Collins at almost the same moment was deciding to bypass Aachen. No matter if innocently done, Schwerin had countermanded an order from the pen of the Fuehrer himself. As proof of it, he had left behind an incriminating letter he would surely come to rue.

The Battle of the Stolberg Corridor

With the decision to bypass Aachen, the VII Corps scheme of maneuver became basically a frontal attack by the corps

[71]

Commanded by Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose, the 3d Armored Division was to pierce the West Wall with two combat commands abreast.18 From Roetgen and Schmidthof, Combat Command B was to drive northeast along the fringe of the Roetgen and Wenau Forests, on an axis marked by the villages of Rott, Zweifall, Vicht, and Gressenich. After crossing the Inde and Vicht Rivers, CCB was to attack over open ground east of Stolberg to come upon Eschweiler, some ten miles inside Germany, from the south. Assailing the face of the corridor near Ober Forstbach, about three miles north of Schmidthof, CCA was to pass through the villages of Kornelimuenster and Brand to hit Stolberg from the west, thence to turn northeast against Eschweiler.

The mission of the 1st Division having changed from capturing to isolating Aachen, the commander, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner, planned to send his 16th Infantry northeast along the left flank of the armor. After penetrating the Scharnhorst Line—the first band of pillboxes—the 16th Infantry was to secure hills that dominate Aachen from the east. The remainder of the 1st Division (minus a battalion attached to the armor) was to build up on high ground south and southeast of Aachen.19

Because the 9th Division still had to move forward from assembly areas near Verviers, the first participation by this division would come a day later. On 14 September one regiment was to move close along the right flank of the armor through the fringes of the Wenau Forest while another regiment attacked northeast through the Monschau Corridor.

The main attack began at dawn on 13 September when the 3d Armored Divi-

[72]

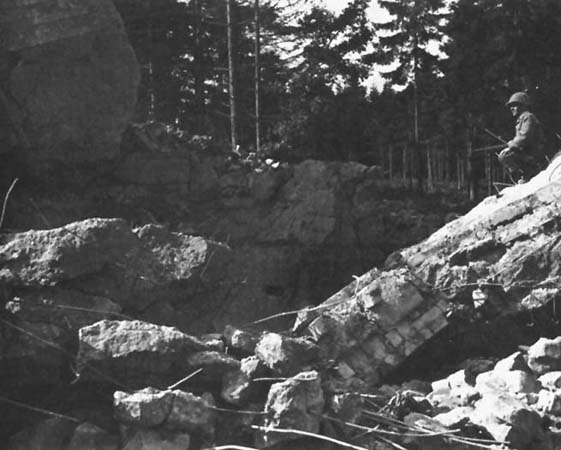

sion's CCB under Brig. Gen. Truman E. Boudinot moved out in two columns. At Roetgen Task Force Lovelady (Lt. Col. William B. Lovelady) eventually had to blast a path through the dragon's teeth after dirt thrown in the big crater in the highway turned to muck. Not until late in the morning did the armor pass the dragon's teeth. As the task force proceeded cautiously northward along a forest-fringed highway leading to the village of Rott, the Germans in eight pillboxes and bunkers along the way turned and fled. In one quick blow Task Force Lovelady had penetrated the thin Scharnhorst Line.20

On the outskirts of Rott the picture changed suddenly when a Mark V tank and several antitank guns opened fire. In the opening minutes of a blazing fire fight, Task Force Lovelady lost four medium tanks and a. half-track. For more than an hour the enemy held up the column until loss of his Mark V tank prompted withdrawal. Because a bridge across a stream north of Rott had been demolished, the task force coiled for the night.

At Schmidthof the second and smaller task force of CCB found the pillboxes in greater density and protected by a continuous row of dragon's teeth. From positions in and around the village, the Germans had superior observation. The task force commander, Lt. Col. Roswell H. King, recognized that to carry the position he needed more infantry than his

[73]

A few miles to the northwest, the other combat command, CCA, attacked at daylight against a nest of four or five pillboxes at a point south of Ober Forstbach. Supported by tanks and tank destroyers deployed along the edge of a woods, the infantry battalion of Task Force Doan (Col. Leander LaC. Doan) got across the dragon's teeth before machine gun fire from the pillboxes forced a halt. Because mortar fire prevented engineers from blowing a gap through the dragon's teeth, tanks could not join the infantry. Their fire from the edge of the dragon's teeth failed to silence the enemy gunners.

In midafternoon, when the attack appeared to have faltered irretrievably, someone made a fortuitous discovery a few hundred yards away along a secondary road. Here a fill of stone and earth built by local farmers provided a path across the dragon's teeth. Colonel Doan quickly ordered his tanks forward.

For fear the roadway might be mined, a Scorpion (flail) tank took the lead, only to founder in the soft earth and block the passage. Despite German fire, Sgt. Sverry Dahl and the crew of the Scorpion helped a tank platoon leader, Lt. John R. Hoffman, hitch two other tanks to pull out the Scorpion. Climbing back into the flail tank, Sergeant Dahl tried the roadway again. This time he rumbled across.

The other tanks soon were cruising among the pillboxes, but without infantry support. Pinned down and taking disconcerting losses, the infantry could not disengage from the first encounter. With panzerfausts the Germans knocked out four of the unprotected tanks and accounted for others with three assault guns of the 394th Assault Gun Brigade. Having detrained at Aachen at midday, these assault guns had been en route to oppose Task Force Lovelady at Rott when diverted to meet the new threat posed by Task Force Doan.21 In an hour Colonel Doan lost half his tanks. Only ten remained.

To guarantee this foray beyond the dragon's teeth, the CCA commander, Brig. Gen. Doyle O. Hickey, called on two platoons of tanks from another task force, plus the attached 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, provided from the division reserve. Together, Task Force Doan and the reinforcements were to push beyond the pillboxes to the village of Nuetheim, which affords command of roads leading deep into the Stolberg Corridor.

At first, these reinforcements merely provided more targets for the German gunners, but as the approach of darkness restricted enemy observation, both tanks and infantry began to move. Blanketing Nuetheim with artillery fire, the armor of Task Force Doan reached the western edge of the village in little, more than an hour. Approaching over a different route, the fresh infantry battalion was not far behind. Because the hour was late, Task Force Doan stopped for the night, the first band of the West Wall left behind.

Slightly to the northwest, the 1st Division's 16th Infantry in the attempt to advance close along the north flank of the armor had run into one frustration after

[74]

Despite the tribulations of the infantry regiment and of Colonel King's task force at Schmidthof, the "reconnaissance in force" on 13 September had achieved two ruptures of the Scharnhorst Line. That both were achieved along the face of the Stolberg Corridor rather than at Aachen went a long way toward convincing the German commander, General Schack, that he had erred in his estimate of American intentions.

General Schack had not been so sure when soon after noon he had ordered General von Schwerin at Aachen to counterattack immediately with the 116th Panzer Division to wipe out the Americans in the Aachen Municipal Forest.22 Reluctantly—for Aachen now would become a battleground—Schwerin had ordered his men to countermarch to the southern outskirts of the city. Augmented by a few replacements, which brought the panzer grenadier battalions to an average strength of about 300, and by half the six assault guns of the 394th Assault Gun Brigade, the panzer division nevertheless succeeded only in driving back American patrols. Though the Germans claimed they had "closed the gap" south of Aachen, the Americans in the forest remained.23

By nightfall of the 13th General Schack had fewer doubts. The main threat apparently was in the Stolberg Corridor. In response to pleas from the commander of the 9th Panzer Division, Generalmajor Gerhard Mueller, Schack sent the only reserves he could muster—a Luftwaffe fortress battalion and a battery of artillery—to Kornelimuenster. The LXXXI Corps operations officer directed headquarters of the 353d Infantry Division to alert its Landesschuetzen battalions to stand by for action because "the enemy will probably launch a drive bypassing Aachen . . . toward the second band of defenses." As the night wore on, engineers began to demolish all crossings of the Vicht River between the Wenau Forest and Stolberg in front of the Schill Line.24

General Collins' plans for renewing the attack on 14 September were in effect a projection of the original effort. On the left wing, the 16th Infantry was to try again to get an attack moving against the Scharnhorst Line. At Nuetheim CCA's second task force coiled behind Task Force Doan in preparation for a two-pronged drive northeast on Kornelimuenster and

[75]

German commanders, for their part, did not intend to fall back on the Schill Line without a fight. Yet to some American units, the German role as it developed appeared to be nothing more than a hastily executed withdrawal. Cratered roads, roadblocks, and what amounted to small delaying detachments were about all that got in the way.

As on the day before, CCB's Task Force Lovelady made the most spectacular advance on 14 September. Sweeping across more than four miles of rolling country, the task force approached the Vicht River southwest of Stolberg as night came. Though the bridge had been demolished, the armored infantry crossed the river, harassed only by an occasional mortar round and uneven small arms fire. Engineers began immediately to bridge the stream. On the east bank the infantry found a nest of 88-mm. guns well supplied with ammunition which could have caused serious trouble had the Germans used them. The infantrymen had to ferret the demoralized crews from their hiding places.

Though General Mueller's 9th Panzer Division by this time had begun to move into the Schill Line, this particular sector was held by one of the 353d Division's Landesschuetzen battalions. Before daylight the next morning, 15 September, the men of this battalion melted away in the darkness.25 When the American armor crossed a newly constructed bridge about noon on 15 September, the pillboxes were silent. Winding up a road toward Mausbach, a village one mile north of a bend in the Vicht River on the planned route toward Eschweiler, the armor passed the last bunker of the Schill Line. Ahead lay open country. Task Force Lovelady was all the way through the West Wall.

CCB's other prong, Task Force Mills (formerly Task Force King but renamed after Colonel King was wounded and succeeded by Maj. Herbert N. Mills), matched Task Force Lovelady's success at first. Because Lovelady's advance had compromised the German positions in the Scharnhorst Line at Schmidthof, Task Force Mills had gone through the line with little enough difficulty. But by midmorning of 15 September, as Mills approached Buesbach, a suburb of Stolberg on the west bank of the Vicht River, the armor ran abruptly into four tanks of the 105th Panzer Brigade and four organic assault guns of the 9th Panzer Division, a force which General Mueller was sending to counterattack Task Force Lovelady.26

Confronted with the fire of Task Force Mills, the German tanks and assault guns fell back. Task Force Mills, in turn, abandoned its individual drive and tied in on the tail of CCB's larger task force.

Elsewhere on 14 and 15 September, General Hickey's CCA had begun to exploit the penetration of the Scharnhorst Line at Nuetheim. By nightfall of 14 September the combat command had advanced four miles to the fringes of Eilen-

[76]

The 16th Infantry, General Hickey knew, would be there soon. After days of frustration with outlying obstacles, this regiment at last had launched a genuine attack against the Scharnhorst Line on 14 September. The leading battalion found the pillboxes at the point of attack hardly worthy of the name of a fortified line. Though skirmishes with fringe elements of the Aachen defense forces prevented the infantry from reaching Eilendorf the first day, the regiment entered the town before noon on 15 September. Fanning out to the west, north, and northeast to seize the high ground, the 16th Infantry by nightfall of 15 September had accomplished its mission. The 1st Division now ringed Aachen on three sides.

Upon arrival of the 16th Infantry, CCA renewed the drive northeast toward Eschweiler. Nosing aside a roadblock of farm wagons on a main highway leading through the northern fringes of Stolberg, the armor headed for the Geisberg (Hill 228), an eminence within the Schill Line. As another unreliable Landesschuetzen battalion fled from the pillboxes, the going looked deceptively easy. Eight U.S. tanks had passed the roadblock when seven German assault guns opened fire from concealed positions. In rapid succession, they knocked out six of the tanks.27

For use in an event like this, General Hickey had obtained permission to supplement his armored infantry with a battalion of the 16th Infantry. He quickly committed this battalion to help his armor clear out the guns and the cluster of pillboxes about the Geisberg. The fighting that developed was some of the fiercest of the four-day old West Wall campaign, but by nightfall the tanks and infantry had penetrated almost a mile past the first pillboxes. Only a few scattered fortifications remained before CCA, like CCB, would be all the way through the West Wall.

From the German viewpoint, the advance of CCA and the 16th Infantry beyond Eilendorf was all the more distressing because it had severed contact between the 116th and 9th Panzer Divisions. Because the 116th Panzer Division estimated that an entire U.S. infantry division was assembling south of Aachen and almost an entire armored division around Eilendorf, General Schack was reluctant to move the 116th Panzer Division from Aachen into the Stolberg Corridor. Almost continuous pounding of Aachen by American artillery strengthened a belief that the city would be hit by an all-out assault on 16 September. Thus the German defense remained divided.28

In the meantime, the battle of the Stolberg Corridor had been broadened by commitment of the 9th Division's 47th Infantry close along the right flank of the 3d Armored Division. So that the regi-

[77]

Commanded by Col. George W. Smythe, the 47th Infantry began to move through Roetgen early on 14 September in the wake of Task Force Lovelady. Even after the route of the main column diverged from that of Task Force Lovelady, resistance was light. One battalion which moved into the Roetgen Forest to come upon Zweifall and Vicht from the east advanced rapidly, but the main column proceeding down a highway got to Zweifall first. While engineers began rebuilding bridges in Zweifall, a second battalion pushed into the forest to eliminate a line of pillboxes.30

On 15 September the situation in the forest near Zweifall and Vicht changed abruptly, not so much from German design as from the confusion of chance encounters with errant Germans of a poorly organized replacement training regiment. Before daylight enemy estimated at less than battalion strength blundered into the perimeter defense of one of the American battalions. One of the first to spot the Germans, Pfc. Luther Roush jumped upon a tank destroyer to fire its .50-caliber machine gun. Though knocked from his perch by an enemy bullet, he climbed up again. Eventually the Germans melted in confusion into the forest. A mess sergeant on his way with food for one of the American companies bumped into a group of the fleeing enemy and captured six.

Another battalion attempting to move through the forest to envelop Vicht ran into a German platoon accompanied by a Mark V tank. Though an American Sherman knocked out the Mark V with its first round, the morning had passed before all these Germans were eliminated. Through the rest of the day both the battalions in the forest found that almost any movement brought encounters with disorganized German units. It was fact nonetheless that in their maneuvers within the forest the battalions actually had penetrated a portion of the Schill Line.

The fighting near Zweifall prompted the German corps commander, General Schack, to order General Mueller's 9th Panzer Division for a third time to counterattack. "9th Panzer Division armor will attack the enemy," Schack directed, "and throw him back behind the West Wall. There is no time to lose!"31 Although General Mueller tried to comply, his force could not advance in the face of heavy artillery, tank, and mortar fire.32

This was not to say that General Mueller could not cause trouble. Contingents of the 9th Panzer Division demonstrated this fact in late afternoon of 15 September, after Task Force Lovelady had crossed the Vicht River and filed past the silent pillboxes of the Schill Line. The

[78]

highway between the villages of Mausbach and Gressenich lies in a shallow valley bordered on the southeastern rise by the Wenau Forest and on the northwestern rise by the high ground of the Weissenberg (Hill 283). The expanse on either side of the highway is broad and open. As Task Force Lovelady reached a point not quite half the distance between the two villages, six or seven German tanks and self-propelled guns opened fire from the flanks. In quick succession they knocked out seven medium tanks, a tank destroyer, and an ambulance. Colonel Lovelady hastily pulled his task force back into Mausbach. Reporting that he had left only thirteen medium tanks, less than 40 percent of authorized strength, Colonel Lovelady asked a halt for the night.

Adroit use of a minimum of tanks and assault guns during the afternoon of 15 September thus had produced telling blows against both main columns of the 3d Armored Division—against CCB at Mausbach and CCA at the Geisberg. To the Germans, these events would have been encouraging even had the LXXXI Corps not been notified that night of the impending arrival of the 12th Infantry Division. First contingents were sched-

[79]

Unaware of this development, the units of the VII Corps renewed their attacks the next day, 16 September. For the most part, the armored combat commands had a bad day of it, though no real cause for concern became evident. At the Geisberg the Germans mounted a local counterattack, but CCA's armored infantry soon disposed of it with concentrated machine gun fire. Nevertheless, when CCA tried to continue northeastward through the industrial suburbs of Stolberg, intense fire from commanding ground brought both armor and infantry up sharply. To the east, CCB shifted the direction of attack from Gressenich to the Weissenberg, only to be denied all but a factory building on the southwestern slope.

The 3d Armored Division's only real advance of the day came in late afternoon when the division commander, General Rose, acted to close a four-mile gap between his two combat commands. Scraping together a small force of tanks to join with the attached 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, he sent them against high ground near Buesbach, within the Schill Line southeast of Stolberg. It was a hard fight, costly in both men and tanks, but the task force held the objective as night came.

The difficulties of the 3d Armored Division were offset by a spectacular advance achieved by the 9th Division's 47th Infantry. With the aid of a captured map, the 47th Infantry cleared Vicht and mopped up nearby pillboxes during the morning. Thereupon, one battalion pressed on two and a half miles northeast through the fringe of the Wenau Forest to seize the village of Schevenhuette, east of Gressenich. This late-comer to the West Wall fighting thus had advanced deeper into Germany than any other Allied unit, approximately ten miles.

The 47th Infantry's deep thrust, which put a contingent of the VII Corps less than seven miles from the Roer at Dueren, augured well for a renewal of the attack the next day. On the other hand, indications began to appear during late afternoon and evening of possibly portentous stirrings on the enemy side of the line. In late afternoon, for example, a platoon of the 16th Infantry patrolling north from Eilendorf reported the enemy approaching the village of Verlautenheide in a column of twos "as far as the eye could see." That night almost every unit along the front noted the noise of heavy vehicular traffic, and the 47th Infantry at Schevenhuette captured a German colonel who had been reconnoitering, presumably for an attack. Even allowing for hyperbole in the patrol's report, these signs had disturbing connotations.

While events in the Stolberg Corridor gave some evidence of reaching a climax, other events transpiring on the left and right wings of the VII Corps exerted a measure of influence on the fight in the corridor. On the left wing, at Aachen, the most significant development was that two regiments of the 1st Division unintentionally maintained the myth that the city was marked for early reduction. Thus they prompted the Germans to con-

[80]

In reality, the 1st Division commander, General Huebner, had no intention of becoming involved among the streets and bomb-gutted buildings of Aachen. He was trying to build a wall of infantry defenses on the southwest, south, southeast, and east of the city while awaiting arrival of the XIX Corps to assist in encircling the city. It was no easy assignment, for the 1st Division's left flank was dangling, and the defensive line eventually encompassed some eight miles of front.

As the 16th Infantry tried on 13 and 14 September to get through the Scharnhorst Line and advance alongside the 3d Armored Division, the 18th Infantry moved up west of the Liège-Aachen highway to push through the Aachen Municipal Forest southwest of Aachen. Before digging in on high ground in the forest, the 18th Infantry penetrated the Scharnhorst Line. A gap between the regiment's left flank and cavalry of the XIX Corps was patrolled by the 1st Division Reconnaissance Troop.

General Huebner's third regiment, the 26th Infantry, was minus a battalion attached to the 3d Armored Division. To the remaining battalions General Huebner gave the mission of following in the wake of the 16th Infantry and filling in to confront Aachen from the south and southeast. By the evening of 15 September, the basic form of the wall about Aachen had set, a half-moon arc extending from the 18th Infantry's positions southwest of the city to the 16th Infantry's advanced hold at Eilendorf.

Stretched to the limit, the 18th and 26th Infantry Regiments patrolled actively toward the buildings and smoke stacks of Aachen a mile and a half away and fought off enemy patrols and local counterattacks. It was no easy assignment, for the Aachen Municipal Forest was damp and cold and the enemy was always close.

The Germans, for their part, could not believe that the Americans would stop short of the city, particularly in light of the condition of the Aachen defenses. Charged with the defense, General von Schwerin's 116th Panzer Division was only a shell. Schwerin had only five organic battalions with a "combat strength"34 of roughly 1,600 men, plus two Luftwaffe fortress battalions and a grenadier training battalion. In armor and artillery, he had 2 Mark IV tanks, 1 Mark V, 1 organic assault gun, 4 assault guns of the 394th Assault Gun Brigade, 9 75-mm. antitank guns, 3 105-mm. howitzers, and 15 150-mm. howitzers.35

To add to the problems of the German commander, the panic which had struck the population of Aachen the night of 12 September came back. Conditions on 14 September, Schwerin said, were "catastrophic." Because no police or civil authorities had returned, a committee of leading citizens begged Schwerin to form a provisional government with the city's former museum director at its head. On top of everything else came a special order from Hitler, this time through military channels rather than through the Nazi

[81]

When police and Nazi officials returned to Aachen on 15 September, they found the civilian evacuation once more in full swing; but that wasn't enough to keep General von Schwerin out of trouble. Schwerin's compromising letter to the American commander had fallen into the hands of the Nazis. You are relieved of your command, they told Schwerin, to stand trial before Hitler's "People's Court."

The fractious Schwerin refused to comply. The men of his division, he believed, would protect him. While he took refuge in a farmhouse north of Aachen, a reconnaissance platoon from his division surrounded his hideout with machine guns. Confident that the battle of Aachen was about to begin, Schwerin determined to stick with his division to the bitter end.

As it gradually became evident that the Americans had no intention of fighting for Aachen immediately, Schwerin at last decided to present himself at Seventh Army headquarters to appear before a military court. Field Marshal von Rundstedt, the Commander in Chief West, apparently had interceded on Schwerin's behalf to get the trial shifted from a "People's Court" to a military tribunal. Rundstedt even proposed that Schwerin be reinstated as commander of the 116th Panzer Division. This last Hitler would not permit, though he agreed to no greater punishment than relegation to the OKH Officer Pool, which since the 20 July attempt on Hitler's life had become a kind of military doghouse. Surprisingly, Schwerin later emerged as commander of a panzer grenadier division and at the end of the war had risen to a corps command in Italy.37

Battle of the Monschau Corridor

At the southern end of the VII Corps front, the 9th Division in the meantime had launched an ambitious attack designed to clear the great forest barrier off the right flank of the Stolberg corridor. Though the 47th Infantry on the fringe of the forest was making the announced main effort of the 9th Division, the course of events had allied this regiment's attack more closely to that of the 3d Armored Division. The real weight of the 9th Division was concentrated farther south in the Monschau Corridor.38

In terms of ground to be cleared and variety of missions to be accomplished, the 9th Division had drawn a big assignment. The division's sector, for example, was more than seventeen miles wide. In sweeping the forest barrier, the division

[82]

In other than a pursuit situation, the 9th Division's responsibilities clearly would have been out of keeping with the division's strength. Even as matters stood the only factor tending to license the scope of the assignment was the expectation that the enemy had no real strength in the forest.

To all appearances, this expectation was correct. On 14 September, that part of the forest lying in the zone of the enemy's LXXXI Corps, north of Roetgen, was virtually unoccupied while General Schack concentrated on holding Aachen and the Stolberg Corridor. South of Roetgen, the weakest of the Seventh Army's three corps, General Straube's LXXIV Corps, had but two infantry divisions, the 347th and the 89th. Hardly any organic forces remained in either division.

The 347th Division, which held the southern portion of the LXXIV Corps front and thus was to be spared direct involvement with the 9th Division, was perhaps the weaker. So understrength was the division that when a training regiment, a fortress battalion, and a "Stomach Battalion"39 were attached, the newcomers exceeded the organic personnel by more than ten to one.40

The other division, the 89th, which held the Monschau Corridor, had few more organic forces left. Of two infantry regiments, one had been destroyed completely and the other had but 350 men. The commander, a Colonel Roesler, long ago had redesignated his artillerymen, engineers, and service troops as infantrymen. The only reinforcements upon arrival in the West Wall were a Landesschuetzen battalion, three Luftwaffe fortress battalions, 14 75-mm. antitank guns, about 450 Russian "volunteers" in a so-called Ost-Batallion (East Battalion), and a grenadier training regiment. The Ost-Batallion and the training regiment provided the 89th Division's only artillery. The former had four Russian 122-mm. howitzers; the latter, two pieces: a German 105-mm. howitzer and an Italian medium (about 150-mm.) howitzer. When the Italian piece ran out of ammunition after two days of firing, the Germans towed it about the front to give an impression of artillery strength.41

The American division commander, Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig, assigned responsibility for pushing through the Monschau Corridor to the 39th Infantry. This regiment and the 47th Infantry, which was making the thrust alongside the 3d Armored Division, together were to clear the forest barrier and converge near Dueren. The remaining regiment, the

[83]

Under Lt. Col. Lee W. Chatfield, the reinforced battalion of the 60th Infantry began operations a day ahead of the rest of the 9th Division by moving to Camp d'Elsenborn, a road center and former Belgian Army garrison ten miles south of Monschau. From here Colonel Chatfield turned north early on 14 September to come upon the Hoefen-Alzen ridge from the southwest. Pushing back a small delaying detachment at the German border, the battalion occupied the border village of Kalterherberg.

Though Colonel Chatfield attacked the Hoefen-Alzen ridge during the afternoon of 14 September, 350 men of the 1056th Regiment, representing the hard core of veterans available to the 89th Division, already had occupied the pillboxes.42 When Chatfield's infantrymen crossed a deep ravine Separating Kalterherberg from the ridge, they met the full force of small arms and machine gun fire from the pillboxes.

To make quick work of the ridge and get on with the main task of driving northeast up the Monschau Corridor, General Craig decided during the evening of 14 September to send the rest of the 60th Infantry to help. Both remaining battalions were to move southeast from Eupen through the Hertogenwald to Monschau. Thereupon a battalion from Monschau and Colonel Chatfield's battalion at Kalterherberg were to press the ridge between them. The remaining battalion was to defend at Monschau; in effect, a reserve.

On 15 September Colonel Chatfield noted no slackening of fire from the pillboxes opposite Kalterherberg. Nor was the weight of the other battalions around Monschau felt appreciably, because the length of the journey from Eupen and demolished bridges at Monschau delayed any real participation by them. Only the advent of supporting tanks on 16 September had any real effect. With the help of the tanks, a battalion from Monschau drove into Hoefen on the 16th, but even then Colonel Chatfield could detect no break at the other end of the ridge. Indeed, the next day the Germans reacted actively with a counterattack which carried to the center of Hoefen before the Americans rallied. Not until 18 September, when Colonel Chatfield abandoned the attack from Kalterherberg and joined the other battalion in Hoefen, did the enemy relinquish his hold on Alzen and the rest of the ridge. By a tenacious defense, the 1056th Regiment had tied up the entire 60th Infantry for five days at a time when the weight of the regiment might have been decisive elsewhere.

General Craig obviously could have used the regiment to advantage elsewhere, particularly in the Monschau Corridor. Here the 39th Infantry had been discovering how much backbone concrete fortifications can put into a weak defensive force.

That part of the Scharnhorst Line blocking the Monschau Corridor was one

[84]

Commanded by Lt. Col. Oscar H. Thompson, the 39th Infantry's 1st Battalion marched almost unopposed on 14 September across the German border into the village of Lammersdorf at the northern edge of the Monschau Corridor. Colonel Thompson then turned his men northward to strike the West Wall at a customhouse a mile away. The customhouse guarded a highway leading northeast through the Roetgen Forest in the direction of Dueren.

Hardly had the infantrymen emerged from Lammersdorf before small arms and mortar fire from pillboxes around the customhouse pinned them to the ground. Though Colonel Thompson sent two of his companies on Separate flanking maneuvers, darkness came before any part of the battalion could get even as far as the dragon's teeth.

Soon after Colonel Thompson met his first fire, the 39th Infantry commander, Lt. Col. Van H. Bond, committed another battalion on Thompson's right. This battalion was to pass east through Lammersdorf, penetrate the Scharnhorst Line, and take the village of Rollesbroich, two miles away. Capture of Rollesbroich would open another road leading northeast through the forest. But here again the Germans stopped the attackers short of the dragon's teeth, this time with antitank fire to supplement the small arms and mortars.

In a renewal of the two-pronged attack on 15 September, the 39th Infantry displayed close co-ordination between infantry and attached tanks and tank destroyers; but the fortifications in most cases proved impervious even to point-blank fire from the mobile guns. Sometimes the Germans inside the pillboxes were so dazed by this fire that the attacking infantry could slip up and toss hand grenades through firing apertures, but this was a slow process which brought reduction of only about seven pillboxes and by no means served to penetrate the entire band.

Attempting to open up the situation, Colonel Bond sent his remaining battalion far around to the north to pass through the Roetgen Forest in a wide envelopment of the customhouse position. By nightfall of 15 September this battalion had reached the rear of the enemy strongpoint, but not until after a full day of tedious, costly small unit fighting was the position reduced.

Three days of bitter fighting had brought a path only a mile and a half wide through the Scharnhorst Line and no advance beyond the line. Even this path could not be used, for strong West Wall positions stretching south to Monschau commanded almost all roads leading to Lammersdorf. By holding between Lammersdorf and Monschau, the Germans still kept a dagger pointed toward the 9th Division's flank and rear, thereby virtually negating the importance of the 60th Infantry's conquest of the Hoefen-Alzen ridge.

[85]

Looking beyond the troubles of the 39th Infantry to the situation of the entire VII Corps, the first five days of West Wall fighting had produced encouraging, if not spectacular, results. Though success probably was not commensurate with General Collins' early hopes, the corps nevertheless had pierced the forward band of the West Wall on a front of twelve miles and in the second belt had achieved a penetration almost five miles wider The VII Corps clearly had laid the groundwork for a breakthrough that needed only exploitation.

On the other hand, was the VII Corps in a position to reap the rewards? The logistical situation, particularly in regard to 105-mm. howitzer ammunition, still was acute. Though supporting aircraft normally might have assumed some of the artillery missions, overcast skies, mists, drizzles, and ground haze had been the rule. Day after day since the start of the West Wall fighting the airmen had bowed to the weather: 13 September—"While we had cloudless skies, nevertheless, haze restricted operations . . . ." 14 September—"Weather again proved to be our most formidable obstacle . . . ." So it had gone, and so it would continue to go: 17 September—". . . 77 sorties were abortive due to the weather." 18 September—"Only two missions were flown due to the weather." Although the weather often was good enough for long-range armed reconnaissance flights, these provided little direct assistance to the troops on the ground.44

Nor was the condition of the divisions of the VII Corps conducive to encouragement. The 3d Armored Division, for example, had only slightly more than half an authorized strength of 232 medium tanks, and as many as 50 percent of these were unfit for front-line duty.45 By nightfall of 16 September, every unit of the VII Corps was in the line, stretched to the limit on an active front which rambled for almost thirty miles from Aachen to Eilendorf to Schevenhuette to the Hoefen-Alzen ridge. Great gaps existed on either flank of the corps and gaps of seven and five miles within the lines of the 9th Division.

The only genuine ground for optimism lay in the deplorable condition of the German units. The 89th Division in the Monschau Corridor, for example, had re-

[86]

To reduce the 9th Panzer Division's responsibility, the corps commander, General Schack, transferred a few hundred men to the headquarters of the almost-defunct 353d Infantry Division and told that division to defend the Wenau, Huertgen, and Roetgen Forests from below Schevenhuette southward to the boundary with the LXXIV Corps. General Brandenberger, in turn, eased the responsibility of the LXXXI Corps by transferring the 353d Division to General Straube's LXXIV Corps and altering the boundary between the two corps to run just south of Schevenhuette.47

These adjustments obviously were feeble moves hardly worthy in themselves of any great expectations. Nevertheless, the Germans did possess a genuine hope in the impending arrival of a fresh division, something which the VII U.S. Corps could not duplicate. The first contingents of the 12th Infantry Division arrived at detraining points along the Roer River early on 16 September. These and subsequent units of the division made a deep impression on a military and civilian population starved for the sight of young, healthy, well-trained soldiers.

Numbering 14,800 men, the 12th Division was organized along the lines of the "Type-1944 Infantry Division." It had three regiments of two battalions each—the 27th Fusilier Regiment and the 48th and 89th Grenadier Regiments—plus a separate infantry unit, the 12th Fusilier Battalion. The division was fully equipped except for an authorized twenty assault guns, a defect which Field Marshal Model at Army Group B remedied by attachment of seventeen assault guns of the 102d Assault Gun Brigade.48 The 12th Artillery Regiment had its authorized strength of nine batteries of 105-mm. howitzers and three batteries of 150-mm. howitzers. The division's antitank battalion had twelve 75-mm. guns. Thanks to priority growing out of specific orders from Hitler and Field Marshal von Rund-

[87]

"Seventh Army will defend the positions . . . and the West Wall to the last man and the last bullet," General Brandenberger declared. "The penetrations achieved by the enemy will be wiped out. The forward line of bunkers will be regained . . . ."50

Cognizant of the dangers of piecemeal commitment, General Schack assured the 12th Division commander, Col. Gerhard Engel, that he would try to wait until the entire division had arrived.51 He kept the promise less than twenty-four hours. Straight from the railroad station at Juelich General Schack sent the first battalion of the 27th Fusilier Regiment to Verlautenheide, north of Eilendorf, whence the battalion was to attack on 17 September to thwart the thrust of CCA, 3d Armored Division, toward Eschweiler. The second battalion of the 27th Fusiliers moved to Stolberg. When the other two regiments and some of the organic artillery detrained before daylight on 17 September, General Schack ordered them to start immediately driving CCB from the vicinity of the Weissenberg (Hill 283) and Mausbach in order to restore the Schill Line southeast of Stolberg.52

Renewing the two-pronged thrust toward Eschweiler on Q September, both combat commands of the 3d Armored Division bumped head on into the German reinforcements. On the left, while CCA was getting ready to attack shortly before dawn, the Germans began a heavy artillery barrage against both CCA and the 16th Infantry at Eilendorf. Plunging out of a woods between Verlautenheide and Stolberg, men of the 27th Fusilier Regiment charged in well-disciplined waves with fixed bayonets. They made a perfect target for prepared artillery and mortar concentrations. Those who got through the curtain of shellfire were cut down close to American foxholes with small arms and machine gun fire. Though the fusiliers tried again in the afternoon and prevented CCA from attacking, they gained no ground. American casualties were surprisingly light. The hardest hit battalion of the 16th Infantry, for example, lost two men killed and twenty-one wounded.

Split into two task forces, CCB attacked at midday to take the Weissenberg. The task force on the left ran almost immediately into an attack by a battalion of the 89th Grenadier Regiment, while the task force on the right encountered a thrust by a battalion of the 48th Grenadier Regiment supported by three tanks. On the left, neither side could gain. On the right, the grenadiers shoved the armored task force back a thousand yards. Late

[88]

The other battalion of the 48th Grenadier Regiment intended to retake Schevenhuette. Here the 47th Infantry commander, Colonel Smythe, had decided to delay his attack in view of the indications of German build-up. In midmorning, a patrol under S. Sgt. Harold Hellerich spotted the Germans moving toward Schevenhuette from the village of Gressenich. Notifying his company commander, Sergeant Hellerich waited for the Germans to enter an open field, then pinned them to the ground with fire from his patrol. At this point gunners in the main positions of the 47th Infantry raked the field with machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire. Observers estimated that of at least 200 Germans who had entered the field no more than ten escaped.

Before daylight the next morning, 18 September, a reinforced company of the 48th Grenadier Regiment sneaked through the darkness to surprise the defenders of a roadblock on the Gressenich-Schevenhuette road. Undetected until too late, the Germans pushed quickly into the village, only to encounter an American tank hidden among the buildings. Assisted by nearby riflemen and machine gunners, the tank's fire virtually wiped out the enemy company. Not until four days later, on 22 September, did the 48th Grenadiers desist in their attempts to retake Schevenhuette, and then only after a full battalion had failed in the face of "murderous" losses. Schevenhuette, the survivors reported, had been turned into a veritable fortress, fully secured by mine fields and barbed wire and tenaciously defended by 600-700 men.54

Even before this action at Schevenhuette, the very first day of active commitment of the 12th Division had shown the division commander, Colonel Engel, how difficult—perhaps how insurmountable—was his task. On the night of 17 September, the Americans had begun to pound the fresh division with artillery fire of alarming proportions. In another few hours Colonel Engel was to report his units hard hit by casualties, particularly a battalion of the 89th Regiment that was down to a hundred men, less than a fifth of original strength.55 Somewhat disheartened by the outcome of the counterattacks and possibly more than a little displeased at the piecemeal commitment of his troops, Colonel Engel called off offensive action for most of the division the next day to permit regrouping.56

On the American side, General Collins had noted that the advent of a fresh German division had changed the situation materially. Though the Germans had gained ground in only isolated instances, he recognized that as long as his

[89]

On the surface General Collins' order to consolidate looked like a sorely needed rest for most of the troops of the VII Corps. Yet the divisions were in the delicate situation of being through the West Wall in some places, being half through in others, and at some points not having penetrated at all. The line was full of extreme zigs and zags. From an offensive standpoint, the penetrations of the Schill Line were too narrow to serve effectively as springboards for further operations to the east; as a defensive position, the line was open to infiltration or counterattack through the great forest between Schevenhuette and Lammersdorf and through the daggerlike redan which the Germans held between Lammersdorf and Monschau. In addition, the positions within the Stolberg Corridor were subject to observation from high ground both east and west of Stolberg. To eliminate these flaws, the VII Corps was destined to attack on a limited scale for most of the rest of September.

The 9th Division drew what looked to be the major role. General Collins directed General Craig to drive through the Roetgen, Wenau, and Huertgen Forests to occupy a clearing near the villages of Huertgen and Kleinhau, about six miles east of Zweifall. This would bring control of the only good road net between the forest barrier and the Roer River and also knit together the two forces in the Stolberg and Monschau Corridors. At the same time, the combat commands of the 3d Armored Division were to seize heights on either side of the Vicht River valley at Stolberg, both to eliminate superior enemy observation and to merge the two penetrations of the Schill Line. Only the 1st Division, in the half-moon arc about Aachen, was to stick strictly to the defense.58

As the fighting continued in the Stolberg Corridor, both German and American units wore themselves out. While the 3d Armored Division's CCA tried to take high ground about the industrial suburb of Muensterbusch, less than half a mile west of Stolberg, and CCB to occupy the high ground east of Stolberg, the enemy's 12th Division and what was left of the 9th Panzer Division continued their futile efforts to re-establish the Schill Line. The result was a miserable siege of deliberate, close-in fighting which brought few advantages to either side.

Attachment of the remnants of the 9th Panzer Division to the 27th Fusilier Regiment made CCA's task at Muensterbusch considerably more difficult.59 Not until late on 19 September did troops of CCA gain a foothold in Muensterbusch from which to begin a costly, methodical mop-up lasting over the next two days.

For two days CCB fought in vain for

[90]

CCB's remaining task was to occupy the Donnerberg (Hill 287), another major height overlooking Stolberg from the east. The assignment fell to Task Force Mills, which with but fourteen effective medium tanks still was stronger than Task Force Lovelady. Screened by smoke and protected on the east by fire of the combat command's tank destroyers, Task Force Mills dashed across a mile of open ground and took the height in one quick thrust.

Holding the Donnerberg was another matter. No sooner had the smoke dissipated than the Germans knocked out half of the tanks. Afraid that loss of the height would compromise a switch position under preparation in the center of Stolberg, the Germans on 22 September mustered a battalion of the 27th Fusilier Regiment to counterattack.60 In the meantime, CCB's Task Force Lovelady had moved up the hill to strengthen Task Force Mills. In danger of losing almost all the combat command at one blow, the division commander, General Rose, authorized withdrawal. Behind a smoke screen the two understrength task forces dashed down the slopes into Stolberg. Here they found sanctuary, for in bitter fighting Task Force Hogan by this time had pushed the enemy back to the switch position across the center of the town.

This was about all either Germans or Americans could accomplish in the Stolberg Corridor. After 22 September the fighting died down. Despite grievous losses, the Germans actually ended up stronger than they had been since General Collins first opened his "reconnaissance in force"; for as the fighting died, reinforcements began to arrive. Unfortunately for the LXXXI Corps commander, General Schack, they came too late to benefit him. On 20 September, because of Schack's connection with the Schwerin affair in Aachen, General Brandenberger relieved him of command. General der Infanterie Friedrich J. M. Koechling took over.

The first major reinforcement to arrive was the 183d Volks Grenadier Division, which had to be employed north of Aachen against the XIX U.S. Corps. Having shored up the line there, General Koechling pulled out the depleted 275th Infantry Division and sent it southward to occupy a narrow sector around Schevenhuette between the 12th Division and the LXXIV Corps. On 23 September a third full-strength division, the 246th Volks Grenadier, entrained in Bohemia with a mission to relieve—at long last—the 9th and 116th Panzer Divisions. These two units were to pass into reserve for refitting and reorganization.61

[91]

On the south wing of the VII Corps, General Collins' order to push through the forest barrier to the clearing around Huertgen and Kleinhau coincided roughly with completion of the 60th Infantry's conquest of the Hoefen-Alzen ridge on 18 September. Relinquishing responsibility for holding the ridge to the 4th Cavalry Group, the division commander, General Craig, left one battalion behind to back up the cavalry and moved the rest of the regiment northward for commitment in the forest. To make up for the battalion left behind, General Craig withdrew the 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, from the fighting in the Monschau Corridor and attached it to the 60th Infantry.

The new drive through the forest in no way lessened the necessity for the 39th Infantry to enlarge the penetration of the West Wall in the Monschau Corridor. Given no respite, the two remaining battalions of the regiment were to fight doggedly for the rest of the month in quest of two dominating pieces of terrain which would secure the penetration. These were Hill 554, within the West Wall south of Lammersdorf, and an open ridge between Lammersdorf and Rollesbroich.

By this time the American battalions had developed closely co-ordinated patterns of maneuver with their attached tanks and tank destroyers, but at best reduction of the pillboxes was slow and costly. Late on 19 September success appeared imminent when tanks and infantry plunged through the line more than two miles toward Rollesbroich, but so fatigued and depleted were the companies that they had no energy left to exploit the gain. Having failed to reach Rollesbroich, the thrust provided no real control of an important road net leading northeast from the village. Hill 554 was finally secured on 29 September after two tenuous holds on it had given way.

In the meantime, the 60th Infantry's attempt to push through the forest and seize the road net around Huertgen and Kleinhau also had begun on 19 September. Something of the confusion the dense forest would promote was apparent on the first day when the lead battalion "attacked" up the main supply route leading to the 47th Infantry at Schevenhuette.

Embracing approximately seven miles, the 60th Infantry front in the forest corresponded roughly to the sector which the enemy's nondescript 353d Infantry Division had assumed when transferred from the LXXXI to the LXXIV Corps. The 60th Infantry commander, Col. Jesse L. Gibney, planned to attack with two battalions moving directly through the center of the forest. This was tantamount to two Separate operations; for as Colonel Gibney knew, secure flanks within a forested zone seven miles wide would become a fancy that one had read about long ago in the field manuals.

The attached 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, commanded by Colonel Thompson, was to move almost due east from Zweifall to seize a complex of trails in the valley of the Weisser Weh Creek, about a mile from the woods line at Huertgen. Colonel Gibney intended later to send this battalion into Huertgen, thence northeast to the village of Kleinhau, only three miles from the flank of the 47th Infantry at Schevenhuette. On the right, a battalion of the 60th Infantry under Colonel Chatfield was to advance southeast from Zweifall, follow the trace of the second

[92]

Experiencing more difficulty from terrain than from the enemy, Colonel Thompson's 1st Battalion reached the valley of the Weisser Weh by nightfall of 20 September. Though Colonel Gibney ordered a push the next day into Huertgen, the enemy awoke at daylight to the battalion's presence. Colonel Thompson's men spent the entire day beating off diverse elements of the 353d Division and trying to get tanks and tank destroyers forward over muddy firebreaks and trails to assist the attack on Huertgen.

Before the battalion could get going on 22 September, orders came to cancel the attack. Colonel Thompson was to move north to back up the 47th Infantry at Schevenhuette where the 12th Division's 48th Regiment was threatening to push in that regiment's advanced position. The division commander, General Craig, also sent the 60th Infantry's reserve battalion northward to Schevenhuette.

Even though neither of these battalions had to be committed actively at Schevenhuette, concern over the situation there had served to erase the penetration through the forest to the valley of the Weisser Weh. By the time Colonel Thompson's battalion became available to return three days later, on 25 September, the Germans had moved into the Weisser Weh valley in strength. Not only that; now Colonel Thompson's men had to go to the aid of Colonel Chatfield's battalion astride the wooded ridge near Deadman's Moor.

Colonel Chatfield's battalion of the 60th Infantry had found the opposition tough from the outset. Strengthened by the pillboxes in the Schill Line, the Germans clung like beggar lice to every position. Two days of fighting carried the battalion over a thousand yards to the western slopes of the objective, the ridge north of Deadman's Moor; but the next morning, 22 September, the Germans began to counterattack.

The counterattack resulted from direct intervention by the Seventh Army commander, General Brandenberger. Concerned about American advances in the forest on 20 September, Brandenberger had transferred an understrength assault gun brigade from the LXXXI Corps to the 353d Division. About this brigade the 353d Division had assembled a battalion each of infantry and engineers, an artillery battery, and five 75-mm. antitank guns.62

Though the counterattack on 22 September made no spectacular headway, close combat raged back and forth along the wooded ridge for the next three days. The fighting centered primarily on possessesion [sic] of a nest of three pillboxes that changed hands time after time. Having entered the forest with only about a hundred men per rifle company, Colonel Chatfield's battalion felt its casualties

[93]

By 25 September losses had become so oppressive that the regimental commander, Colonel Gibney, saw no hope for the battalion's renewing the attack. Altering his plan of maneuver, he sent both his reserve battalion and Colonel Thompson's 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, to take over the assault role. From the contested ridge, these two battalions were to drive south through Deadman's Moor, cut the Lammersdorf-Huertgen road, and make contact to the southwest with that part of the 39th Infantry which had pierced the forward band of the West Wall at the customhouse near Lammersdorf. If this could be accomplished, the 60th Infantry would have carved out a sizable salient into the forest and would have secured at least one of its flanks. Then the regiment conceivably might renew the drive northeast up the highway to the original objective of Huertgen.

Both battalions attacked early on 26 September. Five days later, by the end of the month, the 60th Infantry at last had cut the Lammersdorf-Huertgen highway near Jaegerhaus, a hunting lodge that marked a junction of the highway with a road leading northwest through the forest to Zweifall. But it had been a costly, frustrating procession of attack followed by counterattack, a weary, plodding fight that pitted individual against individual and afforded little opportunity for utilizing American superiority in artillery, air, and armor. Enemy patrols constantly infiltrated supply lines. Although units at night adopted the perimeter defense of jungle warfare, the perimeter still might have to be cleared of Germans before the new day's attack could begin. So heavy a toll did the fighting take that at the end of the month the 60th Infantry and the attached battalion from the 39th Infantry were in no condition to resume the attack toward Huertgen.

The Germans had effectively utilized terrain, the West Wall, and persistent small-unit maneuver to thwart the limited objective attack of the widespread 9th Division. As others had been discovering all along the First Army front, General Craig had found his frontage too great, his units too spent and depleted, and a combination of enemy and terrain too effective to enable the division to reach its objectives. In the specialized pillbox and forest warfare, "the cost of learning 'on the job' was high."63

As events were to develop, the 9th Division was the first of a steady procession of American units which in subsequent weeks were to find gloom, misery, and tragedy synonymous with the name Huertgen Forest. Technically, the Huertgen Forest lies along the middle eastern portion of the forest barrier, but the name was to catch on with American soldiers to the exclusion of the names Roetgen and Wenau. Few could distinguish one dank stretch of evergreens from another, one abrupt ridge from another. Even atop the ridges, the floor of the forest was a trap for heavy autumn rains. By the time both American and German artillery had done with the forest, the setting would

[94]

look like a battlefield designed by the Archfiend himself.

The VII Corps was stopped. "A combination of things stopped us," General Collins recalled later. "We ran out of gas—that is to say, we weren't completely dry, but the effect was much the same; we ran out of ammunition; and we ran out of weather. The loss of our close tactical air support because of weather was a real blow." The exhausted condition of American units and the status of their equipment also had much to do with it. It was a combination of these things, plus "really beautiful" positions which the Germans held in the second band of the West Wall.64

General Collins had gone into the West Wall on the theory that "if we could break it, then we would be just that much to the good; if we didn't, then we would be none the worse."65 Perhaps somewhere between these conditions lay the true measure of what the VII Corps had accomplished. The West Wall had been penetrated, but the breach was not secure enough nor the VII Corps strong enough for exploitation.

The fighting had cost the Germans dearly in casualties. In a single week from 16 to 23 September, for example, the 12th Division had dropped from a "combat strength" of 3,800 men to 1,900, a position from which the division was not to recover fully through the course of the autumn fighting. During a similar period, the 9th Panzer Division had lost over a thousand men representing two thirds of its original combat strength. One unit, the 105th Panzer Grenadier Battalion, had been reduced from 738 officers and men to 116. Only the 116th Panzer Division in the relatively quiescent sector about Aachen had avoided appreciable losses.66 On the other hand, the Germans had bought with those losses a priceless commodity. They had bought time.

As September came to an end, the VII Corps all along the line shifted to defense. Before General Collins could hope to renew the attack, he had somehow to shuffle the front to release some unit with which to attack.67 The logical place to shuffle was in the defensive arc about Aachen; for the next fight lay not to the east or northeast but in conjunction with the XIX Corps against the city which General Collins had by-passed in favor of more critical factors like dominant terrain and the West Wall.

[95]