CHAPTER XXIII The Battle Between the Salm and the Ourthe The Sixth Panzer Army had begun the Ardennes counteroffensive with two distinct missions in hand: the first, to cross the Meuse River between Liège and Huy as a prelude to the seizure of Antwerp; the second, to wheel a cordon of divisions onto a blocking line extending due east of Liège to cover the depth of the advancing army and to deny incoming Allied reinforcements the use of the highway complex southeast of Liège. Constricted by the American grip on the Elsenborn Ridge "door post" (as the German High Command called this position), the Sixth Panzer Army had bumped and jostled some of its divisions past Elsenborn and on toward the west, but had failed to achieve the momentum and maneuver room requisite to the assigned missions. The armored gallop for the Meuse had foundered on the north bank of the Amblève River when Peiper's mobile task force from the 1st SS Panzer Division had run squarely against the 30th Infantry Division. The 12th SS Panzer Division, supposed originally to be running mate with the 1st SS Panzer, had become involved in a costly and time-consuming fight to budge the American "door post," failing thereby to keep its place in the German scheme of maneuver. Therefore, the task-and glory-of leading the drive across the Meuse had passed to the Fifth Panzer Army. But General Sepp Dietrich's SS formations had failed quite as signally to achieve the second mission-to create the blocking line east of Liège. Left free to deploy along the proliferating highway system southeast of Liège, the Americans had been able to throw two fresh corps into defensive array along the Salm, the Ourthe, the Lesse, and L'Homme Rivers, thus still further obstructing the advance of the Sixth Panzer and, more important, endangering the exposed right flank of the Fifth Panzer as it maneuvered before the Meuse. (See Map VIII.) By 24 December the westernmost armored columns of the Fifth Panzer Army had been slowed to a walk quite literally, for the OB WEST orders on that date called for the advance toward the Meuse "to proceed on foot." In part the loss of momentum arose from supply failure, but basically the slowing process stemmed from the failure of the Sixth Panzer Army to form a protected corridor for its neighbor to the south [578] and so to cover the flank, the rear, and the line of communications for Manteuffel's salient. It was apparent by the 24th to all of the higher German commanders that the advance must be strengthened in depth and-if possible-enlarged by pushing out the northern flank on the Marche plateau. German intelligence sources now estimated that the Allies were in the process of bringing a total of four armored and seven infantry divisions against the northern flank between the Salm and Meuse Rivers. The Sixth Panzer Army had to transfer its weight to the west. Hitler, who had been adamant that Sepp Dietrich should drive the Americans back from the Elsenborn position, finally granted permission on 24 December to give over the battle there and move in second-line divisions capable only of defensive action. Rundstedt already had gone on record that it was "useless" to keep five divisions in the Elsenborn sector. Neither Rundstedt nor Model had completely given up hope that the point of the Sixth Panzer Army might shake free and start moving again, for the German successes in the Vielsalm area at the expense of the American XVIII Airborne Corps promised much if Dietrich could reinforce his troops on this western flank. Nonetheless, the main play still would be given the Fifth Panzer Army. The orders passed to Dietrich for 24 December were that his attack forces in the Salm River sector should push hard toward the northwest to seize the high ground extending from the swampy plateau of the Hohes Venn southwest across the Ourthe River. In the opinion of Rundstedt's staff the Fifth Panzer Army was at tactical disadvantage because its westernmost divisions, which had followed the level path of the Famenne Depression at Marche and Rochefort, were under attack from American forces holding command of the high ground on the Marche plateau to the north. It therefore seemed essential for the Sixth Panzer to establish itself on the same high ground if it was to relieve the pressure on Manteuffel's open and endangered north flank. In theory the strategic objectives of the Sixth Panzer were Liège and Eupen, but the German war diaries show clearly that Rundstedt (and probably Model) hoped only that Dietrich could wheel his forward divisions into a good position on defensible ground from which the Fifth Panzer Army could be covered and supported.1 On the morning of 24 December the Sixth Panzer Army was deployed in an uneven stairstep line descending southwest from the boundary with the Fifteenth Army (near Monschau) to the Ourthe River, newly designated as the dividing line between the Fifth and Sixth. In the Monschau-Höfen sector the LXVII Corps held a north-south line, the corps' front then bending at a right [579] angle past the Elsenborn ridge line. This corps front coincided almost exactly with that of the American V Corps. The I SS Panzer Corps continued the German line west along the Amblève River where it faced the reinforced 30th Infantry Division, but at the juncture of the Amblève and the Salm the line bent south at a sharp angle, following the east bank of the latter river as far as Vielsalm. This section of the German line opposite the 82d Airborne Division was poorly manned. The 1st SS Panzer Division (the only division available to the corps) had put troops across both the Amblève and Salm, but by the 24th the 1st SS, already badly beaten, was able to do little more than patrol its corner position. The fall of St. Vith had opened the way for the westernmost corps of the Sixth Panzer Army to form a base of attack running generally west from Vielsalm and the Salm River to the crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture (Parker's Crossroads). This corps, the II SS Panzer, had relieved the 560th Volks Grenadier Division of its attack against the south front of the 82d Airborne and 3d Armored Divisions, the 560th sideslipping further west to take over the front, facing elements of the 3d Armored Division between the Aisne and Ourthe Rivers. The diagonal course of the Ourthe valley and the broken nature of the ground lying east of it posed an organization and command problem for both Germans and Americans. Those elements of the 3d Armored east of the Ourthe, though belonging to Collins' VII Corps, were actors in the story of the XVIII Airborne Corps. The same lack of neat accord between battle roles and order of battle listings was reflected on the German side of the line. There the LVIII Panzer Corps, forming the right wing tip of the Fifth Panzer Army, lay astride the Ourthe with its armor (the 116th Panzer) on the west bank and the bulk of its infantry (the 560th Volks Grenadier Division) on the east bank, echeloned in front of the incoming II SS Panzer Corps. When, on the night of 22 December, the advance guard of Bittrich's II SS Panzer Corps first descended on the American-held crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture, General Bittrich had only one regiment of the 2d SS Panzer Division available for mounting this new Sixth Panzer Army attack. On 23 December, when the Americans at the crossroads finally succumbed to superior numbers, Bittrich had nearly all of the 2d SS at his disposal and the advance guard of his 9th SS Panzer Division was nearing the east bank of the Salm. Field Marshal Model had just wheeled the two infantry divisions of the LXVI Corps northward with orders to attack astride the Salm valley, thus bolstering Bittrich's right flank, now insecurely held by the decimated 1st SS Panzer Division. General Bittrich had been promised still more forces for his attack to the northwest. The Fuehrer Begleit Brigade, re-forming after its battles in the St. Vith sector, was en route to join the 2d SS Panzer at the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads. The 12th SS Panzer Division, so Bittrich was told, would be relieved in the Elsenborn sector and hurried to the new Sixth Panzer front. Finally, Hitler himself would order the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division moved from the Elsenborn battle to the fight looming between the Salm and the Ourthe. Bittrich has not recorded any gloomy suspicion of [580] this potential plethora of riches, but as a veteran commander he no doubt recognized the many slips possible between cup and lip: the increasing poverty of POL, Allied air strikes against any and all moving columns, the poor state of the few roads leading back through the narrow Sixth Panzer zone of communications, and, finally, the pressing and probably overriding demands of the Fifth Panzer Army with one foot entangled at Bastogne and the other poised only a few miles from the Meuse. The German attack plans, formulated during the night of 3 December as the 2d SS Panzer mopped up the last of the defenders around the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads, called for a continuation of the 2d SS Panzer attack northwest, astride the Liège highway on the 24th. The immediate objective was the Manhay crossroads five miles away. Once at Manhay the attack could either peel off along the road west to Hotton, there freeing the Fifth Panzer Army formations hung up at the Hotton-Marche road, or swing northwest to gain the main Ourthe bridge site at Durbuy. The II SS Panzer Corps attack base on the Salmchâteau-La Roche road seemed secure enough. On the left the 560th had driven a salient clear to Soy, a distance of eleven miles. On the right American stragglers from St. Vith were fighting to escape northward through or around Salmchâteau. The 82d Airborne Division still had an outpost line covering much of the road west of Salmchâteau, but the Fuehrer Begleit Brigade was in position to roll back the Americans in this sector. In any case the 9th SS Panzer Division would, in a matter of hours, cross the Salm River in the Vielsalm-Salmchâteau area and swing northwest to march forward at the right shoulder of the 2d SS Panzer. This was the outline plan for 24 December. On the morning of 24 December the American troops between the Salm and Ourthe Rivers were deployed on a front, if so it can be called, of over thirty miles. This, of course, was no flankless and integrated position. On the west wing in particular the American line consisted of small task forces from the 3d Armored, each defending or attacking a hill or hamlet in what were almost independent operations. In the Salm sector the 82d Airborne Division faced north, east, and south, this disposition reflecting the topsy-turvy condition encountered when the division first came in to cover the deployment of the XVIII Airborne Corps. The 504th Parachute Infantry (Col. Reuben H. Tucker), on the division north flank, was bent at an angle reaching west and south from the confluence of the Amblève and Salm Rivers, a position assumed while Kampfgruppe Peiper was on the rampage west of Stavelot. The 505th Parachute Infantry (Col. William E. Ekman) over-watched the Salm from positions on the west bank extending from Trois Ponts south past Grand Halleux. The 508th Parachute Infantry (Col. Roy E. Lindquist) held a series of bluffs and ridges which faced the bridge sites at Vielsalm and Salmchâteau, then extended westward overlooking the La Roche highway. The 325th Glider Infantry (Col. Charles Billingslea) held the division right flank and continued the westward line along the ridges looking down on the La Roche road; its wing was affixed to the village of Fraiture just northeast of the crossroads where the 2d SS Panzer had begun its penetration. [581]

PRIME MOVER TOWING AN 8-INCH HOWITZER ALONG A ROAD NEAR MANHAY From Fraiture west to the Ourthe the American "line" was difficult to trace. Here elements of the 3d Armored Division and two parachute infantry battalions were attempting to hold an extension of the American line west of Baraque de Fraiture, none too solidly anchored at Lamorménil and Freyneux. 2 At the same time the Americans' exposed right wing was counterattacking to erase the German penetration which had driven as far north as the Soy-Hotton road and threatened to engulf Task Force Orr, standing alone and vulnerable at Amonines on the west bank of the Aisne River. Two regimental combat teams from the as yet untried 75th Infantry Division were en route to help shore up the ragged 3d Armored (-) front but probably would not reach General Rose until the evening of the 24th. There were some additional troops immediately at hand to throw in against the II SS Panzer Corps. All through the afternoon and evening of the 23d the St. Vith defenders poured through the American lines. When the last column, [582] led by Colonel Nelson of the 112th Infantry, reached the paratroopers, some 15,000 men and about a hundred usable tanks had been added to Ridgway's force west of the Salm. Aware of the increasing enemy strength south of Manhay, General Ridgway sent troops of the 7th Armored and the remnants of the 106th Division to extend and reinforce the right flank of the 82d Airborne. At the same time, he ordered CCB, 9th Armored, to assemble as a mobile reserve around Malempré, east of the Manhay road, and to back up the American blocking position just north of the Baraque de Fraiture. Ridgway, however, recognized that the 7th Armored was much below strength and that the rugged, forested terrain on his front was poor for armor; so, on 24 December, he asked Hodges to give him an infantry division. The Battle at the Manhay Crossroads By dawn on 24 December Generalleutnant Heinz Lammerding, commander of the 2d SS Panzer, had brought his two armored infantry regiments into line north of the Baraque de Fraiture crossroads. The zone on the west side of the road to Manhay was given over to the 3d Panzer Grenadier, that east of the road to the 4th Panzer Grenadier. Both groups possessed small panzer detachments, but the bulk of Lammerding's tanks were left bivouacked in wood lots to the rear. The terrain ahead was tactically negotiable only by small packets of armor, and in the past twenty-four hours the amount of POL reaching the westernmost German columns had been gravely reduced. Lammerding had to husband his fuel for a short, direct thrust. The assault, however, was initiated by the right wing of the 560th Volks Grenadier Division, which had provided the cover for the 2d SS Panzer assembly. During the previous night the 1130th Regiment, now reduced to fewer than 500 men, had slipped between the 3d Armored outposts manned by Task Force Kane at Odeigne and Freyneux. The American outpost in Odeigne having been withdrawn, a German assault gun platoon supported by a company or two of grenadiers moved into the open to attack Freyneux. About a dozen American tanks, half of them light, remained quiet in their camouflaged positions inside Freyneux. The German infantry entered the village while the assault guns closed in to give support; this was what the short-barreled Shermans needed. They destroyed or crippled over half the guns, an American tank destroyer shelled the enemy infantry out of the houses, and the skirmish abruptly ended. A second German force meanwhile had made a pass at the third of Kane's roadblock positions here in the valley, Lamorménil, just west of Freyneux. In this case the enemy first perched up on the heights, trying to soften the American detachment with long-range assault gun fire, but when the guns moved down into the village for the kill the American tankers promptly knocked out the leaders. At twilight further enemy adventures in this sector were abandoned since the possession of Odeigne opened the way for a flanking thrust at the Manhay crossroads and the seizure of Grandménil on the road to Hotton and the Ourthe. In any case the 1130th had sustained such severe losses during the day [583]

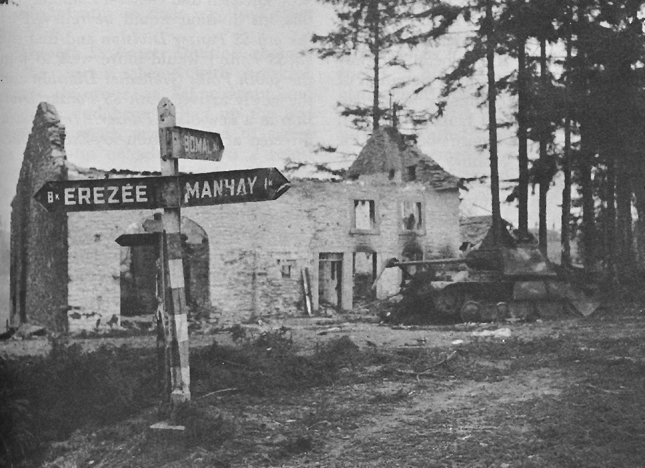

MANHAY CROSSROADS that it was temporarily out of action. Kane's task force was not hit again and withdrew to the north under cover of fog and artificial smoke on the 26th. It will be recalled that Task Force Brewster had established a roadblock position athwart the Manhay road late on the 23d. During the night German infantry had filtered into and through the surrounding woods, taking possession of Odeigne-only 1,200 yards to the west-in the process, but Brewster's tanks and guns were deployed with enough infantry to hold the enemy riflemen at arm's length. For any one of a number of reasons General Lammerding did not essay a tank assault in force to oust Brewster from the highway. The Americans in part were masked from direct observation, the ground was poor, the German main force needed a wider corridor than possession of twenty-two feet of pavement would provide, the American fighter-bombers were exceedingly busy-whatever his reason Lammerding did no more during the morning than to probe at Brewster's position while waiting for elbow room to be won a mile or two on either side of the highway. Remer's Fuehrer Begleit Brigade, which had the task of driving the Americans back and giving free play to the east wing of the 2d SS Panzer, moved up past Salmchâteau in the early morning and struck through the village of Regné, where a platoon of paratroopers and three 57-mm. antitank guns proved no match for the panzers. Possession of Regné opened the way into the Lienne River valley, thus endangering the 82d Airborne flank and line of supply. More immediately, the German coup de main at Regné opened the way for the [584] 4th Panzer Grenadier to initiate a pincers attack against the 2d Battalion of the 325th Glider Infantry at Fraiture, the western corner post of the 82d Airborne defenses. Hard on the heels of the German infantry, the point of the Fuehrer Begleit swung to take a hand against Fraiture. Here the 2d Battalion, "tired of attempting to stop armor with tired men and thin air," received permission about noon to withdraw a half-mile to the northeast. The battalion fell back with almost no loss, although it had to take on one of the flanking detachments from the 4th Panzer Grenadier en route. While this rear guard action was in progress, the reserve company of the 325th and a medium tank company from the 14th Tank Battalion counterattacked at Regné and wrested it from the tank detachment left there by Remer. This village no longer had a place in the Fuehrer Begleit scheme. The brigade was shifting to Fraiture, and even before its columns could close new orders arrived from Marshal Model which would send Remer and his panzers hurrying posthaste to join the Fifth Panzer Army farther west. During the morning of the 24th a series of somewhat un-coordinated and disconnected steps had been taken by the American commanders facing the threat posed by the II SS Panzer Corps. General Ridgway had no direct authority over the 3d Armored Division troops, who belonged to the VII Corps, and the units which had just come out of the St. Vith salient were scattered hither and yon without much regard to tactical unity or proper integration in the wire and radio command net earlier established for the XVIII Corps formations west of the Salm. On the night of the 23d Ridgway had ordered Hasbrouck to collect a force from the 7th Armored sufficient to hold the Manhay junction and to tie this force to the 82d Airborne positions. Hasbrouck selected Colonel Rosebaum's CCA, which had come through the withdrawal from St. Vith in fair shape. The first part of the 7th Armored mission was carried out in the early morning of the 24th when a task force outposted Manhay and its radial roads, but a reconnaissance detachment sent southeast to contact the 82d Airborne was halted by a blown bridge. There remained a gap, therefore, between the 7th Armored advance task force, which was assembling at noon in the vicinity of Malempré, southeast of Manhay, and the new 82d Airborne flank being formed north of Fraiture. On the west wing coordination between the 7th Armored and the 3d Armored task forces would prove to be very complicated indeed. That portion of General Rose's division east of the Ourthe River by now was fighting two separate battles, one in the Hotton-Soy sector where the 560th Volks Grenadier penetration had occurred, and the other along the series of blocking positions that reached from Task Force Brewster's handhold on the Manhay road, through Freyneux and Lamorménil, and northwest to Orr's position at Amonines on the Aisne River. To give cohesion to the 3d Armored defensive battle east of the Aisne, General Rose recalled Brig. Gen. Doyle Hickey, his CCA commander, from the 84th Division sector and placed him in command there. Early in the afternoon Hickey met Colonel Rosebaum, who had just brought the main force of CCA, 7th Armored Division, into Manhay, and [585]

ELEMENTS OF THE 3D ARMORED DIVISION ADVANCING NEAR MANHAY the two worked out a plan to coordinate the efforts of their respective commands. The 7th Armored troops would deploy on the high ground south of Manhay and extend their line across the highway and along the ridge leading east to Malempré. Thereafter Task Force Brewster would attempt to withdraw from its beleaguered roadblock position, retire through the 7th Armored line, and swing westward to bolster the 3d Armored outposts in the Lamorménil-Freyneux sector. Colonel Rosebaum's command took the rest of the daylight hours to carry out the planned deployment, but before Task Force Brewster could begin its retirement new orders arrived from the XVIII Airborne Corps. Field Marshal Montgomery had visited Ridgway's headquarters in midmorning and had decided at once that the American front between the Ourthe and the Salm was too full of holes and overextended. 3 Furthermore he was concerned with the increasing German pressure on the western flank of the First Army as this was represented by movement against the [586] VII Corps flank at Ciney. He told the First Army commander, therefore, that the XVIII Airborne Corps must be withdrawn to a shorter, straighter line and that the VII Corps could be released from "all offensive missions." General Collins might, on his own volition, draw the left wing of the VII Corps back on the line Hotton-Manhay, conforming to Ridgway's regroupment.4 The American line to be formed during the night of 24 December was intended to have a new look. The 82d Airborne would pull back to a much shorter front extending diagonally from Trois Ponts southwest to Vaux Chavanne, just short of Manhay. CCA of the 7th Armored would withdraw to the low hills north of Manhay and Grandménil (although Colonel Rosebaum protested that the high ground now occupied by his command south and southeast of Manhay was tactically superior) and retain a combat outpost in the valley at Manhay itself. The 3d Armored task forces had been promised support in the form of the 289th Infantry, due to arrive on Christmas Eve; so Hickey mapped his new position to rest on the Aisne River with its east flank tied to Grandménil and its west resting on Amonines. Since the 289th, a green regiment, would be put into an attack on the morning of the 25th to clear the Germans out of the woods near Grandménil, Hickey decided that Task Force Kane would have to remain in its covering position at Freyneux and Lamorménil while the 289th assembled, and that Task Force Brewster-thus far exposed only to desultory attack-would have to hold on at the Manhay road until the 7th Armored had redressed its lines. A glance at the map will show how difficult the series of American maneuvers begun on Christmas Eve would be and how tricky to coordinate, particularly in the Manhay sector. Yet it was precisely in this part of the front that communications had not been thoroughly established and that tactical cohesion had not as yet been secured. As shown by later events, communication between the 3d Armored and the 7th Armored commanders and staffs failed miserably. There had been so many revisions of plans, orders, and counterorders during the 24th that Colonel Rosebaum did not receive word of his new retrograde mission until 1800. The withdrawal of CCA, 7th Armored, and the elements of CCB, 9th Armored, south and southeast of Manhay was scheduled to begin at 2230 and most of these troops and parts of the 3d Armored would have to pass through Manhay. Toward Manhay, on the night of 24 December, the main body of the 2d SS Panzer Division was moving. The seizure of Odeigne the night before had opened a narrow sally port facing Grandménil and Manhay, but there was no road capable of handling a large armored column between Odeigne and the 2d SS Panzer assembly areas south of the Baraque de Fraiture. On the 24th the commander of the 3d Panzer Grenadier Regiment secured General Lammerding's approval to postpone a further advance until the German engineers could build a road through the woods to Odeigne. By nightfall on Christmas Eve this road was ready-and the Allied fighter-bombers had returned to their bases. The 3d Panzer Grenadier [587]

TROOPS OF THE 84TH INFANTRY DIVISION DIGGING IN now gathered in attack formation in the woods around Odeigne, while tanks of the 2d Panzer Regiment formed in column along the new road. To the east the 4th Panzer Grenadier sent a rifle battalion moving quietly from Fraiture through the woods toward Malempré. By 2100, the hour set for the German attack, the column at Odeigne was ready. Christmas Eve had brought a beautifully clear moonlit night, the glistening snow was hard-packed, tank-going good. About the time the German column started forward, the subordinate commanders of CCA, 7th Armored, received word by radio to report in Manhay, there to be given new orders-the orders, that is, for the general withdrawal north. The commander of the 7th Armored position north of Odeigne (held by a company of the 40th Tank Battalion and a company of the 48th Armored Infantry Battalion) had just started for Manhay when he saw a tank column coming up the road toward his position. A call to battalion headquarters failed to identify these tanks, but since the leader showed the typical blue exhaust of the Sherman, it was decided that this must be a detachment from the 3d Armored. Suddenly a German bazooka blasted [588] from the woods where the Americans were deployed; German infantry had crept in close to the American tanks and their covering infantry. Four of the Shermans fell to the enemy bazooka men in short order and two were crippled, but the crippled tanks and one still intact managed to wheel about and head for Manhay. The armored infantry company asked for permission to withdraw, got no answer, and finally broke-the survivors turning toward Manhay. A thousand yards or so farther north stood another 7th Armored roadblock, defended by an understrength rifle company and ten medium tanks which had been dug in to give hull defilade. Again the Americans were deceived by the Judas Goat Sherman leading the enemy column. When almost upon the immobile American tanks the Germans cut loose with flares. Blinded and unable to move, the ten Shermans were so many sitting ducks; most were hit by tank fire and all were evacuated by their crews. The American infantry in turn fell prey to the grenadiers moving through the woods bordering the road and fell back in small groups toward Manhay. It was now a little after 2230, the hour set for the 7th Armored move to the new position north of Manhay. The covering elements of the 3d Armored had already withdrawn, but without notifying CCA of the 7th.5 The light tank detachment from Malempré had left that village (the grenadier battalion from the 4th Regiment moving in on the tankers' heels), the support echelon of CCB, 9th Armored, already had passed through Manhay, and the headquarters column of CCA, 7th Armored, was just on its way out of Manhay when the American tanks that had escaped from the first roadblock position burst into the latter village. Thus far the headquarters in Manhay knew nothing of the German advance-although a quarter of an hour earlier the enemy gunners had shelled the village. A platoon commander attempted to get two of his medium tanks into firing position at the crossroads itself, but the situation quickly degenerated into a sauve qui peut when the leading panzers stuck their snouts into Manhay. In a last exchange of shots the Americans accounted for two of the panzers but lost five of their own tanks at the rear of the CCA column. Thus Manhay passed into German hands. The medium tanks and armored infantry that had started to follow the light tank detachment out of Malempré circled around Manhay when they heard the firing. Working their way north, the road-bound tanks ended up at Werbomont while the riflemen moved cross-country to reach friendly lines about two thousand yards north of Manhay. There Colonel Rhea, commanding the 23d Armored Infantry Battalion, had formed a defense on the hills bordering the highway to Werbomont and Liège. All this while Major Brewster and the task force astride the highway south of Manhay had been under fire, but the enemy had refused to close for a final assault. It soon became apparent, however, that this small American force was on its own and that the Germans were in strength to the rear. Brewster [589] radioed for permission to pull out; when it was granted he turned east toward Malempré, hoping to find this spot still in friendly hands. The German battalion which had come up from Fraiture met Brewster's column at Malempré and shot out his two lead tanks. Since there was no other road, Brewster ordered his vehicles abandoned and released his men to reach the American lines on their own-most of his command made it. Although the 2d SS Panzer had preempted a piece of the new American line, General Lammerding was none too pleased by the results of the Christmas Eve attack. His tanks had bitten only a small piece from the tail of the "long American column" reported fleeing Manhay. (Their inability to do better his officers ascribed to the difficulty attendant on bringing more than one or two tanks into firing position on the narrow roads.) The accompanying infantry formations had failed to coordinate their advance with that of the armored assault from Odeigne and to seize, as planned, the wooded heights northwest of Manhay and Grandménil. Lammerding and the II SS Panzer Corps commander, General Bittrich, agreed that the 1st SS Panzer should continue the battle with shock tactics aimed at securing an enlarged maneuver space east and west of Manhay. The 9th SS Panzer (which had crossed the Salm River behind the withdrawing 82d Airborne) was to align itself as rapidly as might be with Lammerding's division in an advance up the Lienne valley toward Bras, commanding the high ground northeast of Manhay. The fall of Manhay roused considerable apprehension in the American headquarters. General Ridgway saw that his new corps defense might be split in the center before it could properly solidify. General Hodges sent message after message to the XVIII Airborne Corps insisting that Manhay must be retaken, for it was all too clear that if the Sixth Panzer Army could reinforce the Manhay salient, Liège and the Meuse bridgehead would be in grave danger.6 In addition, he pressed Field Marshal Montgomery for more divisions to backstop the threatened sector between the Salm and the Ourthe. By daylight on the 25th Colonel Rhea had amassed a sizable force on the hills north of Manhay, his own armored infantry battalion, reinforced by the 2d Battalion of the 424h Infantry, plus the tanks and stragglers that had worked their way past the enemy in Manhay. The Germans scouted this position, then broke contact-probably discouraged by twelve P-47's from the 389th Squadron who claimed ten tank kills on this mission. To the east General Gavin sent the 1st Battalion of Billingslea's glider infantry to secure his division's right flank at Tri-le-Cheslaing, a tiny collection of houses in the valley about 2,000 yards east of Manhay. For some reason, perhaps the lack of coordination which had bothered Lammerding, the 4th Panzer Grenadier had not pushed forward and the village was unoccupied. Thus far the 82d Airborne had had no physical contact with CCA of the 7th Armored, but Gavin was apprised by radio that his western neighbor was in position on the Werbomont-Liège highway. [590] General Bittrich had no intention of pushing the 2d SS Panzer north toward Liège. Although the time at which the II SS Panzer Corps commander received his orders is uncertain, it is known that by the small hours of 25 December Bittrich was embarked on a new mission assigned by General Kraemer, the Sixth Panzer Army chief of staff. The 2d SS Panzer now was to turn west from Manhay, drive along the lateral road to Erezée on the Aisne River, then pivot northwest to seize the Ourthe bridgehead at Durbuy, all this as a maneuver to strike the American VII Corps in the flank and break the deadly grasp Collins and Harmon had on the throat of the Fifth Panzer armored columns in the Celles-Marche sector. For such a change of axis the Germans needed turning room, and they could best gain it by seizing the road center at Grandménil just west of the Manhay crossroads. As a result, then, the major part of the 2d SS Panzer would turn away from the 7th Armored to engage General Hickey's troops from the 3d Armored. Richardson's task force, really little more than a light tank platoon, had fallen back from Manhay to Task Force Kane's roadblock at Grandménil. Here Kane had his trains and a platoon of tank destroyers. The Panthers, followed by the German infantry, pursued the Americans into Grandménil. The American tank destroyers attempted a fight from the high ground west of the village but had no infantry in support and, as the grenadiers close in, withdrew westward along the road to Erezée. By 0300 on 25 December then, the Germans held Grandménil and were poised on the way west. It will be remembered that the new 289th Infantry (Col. Douglas B. Smith) had come into assembly areas west of Grandménil on Christmas Eve in preparation for a dawn attack to drive the enemy off the wooded hills southwest of Grandménil.7 The lead battalion, the 3d, actually had started forward from its bivouac in Fanzel when it encountered some 3d Armored tanks (the latter supposed to be screening the 289th deployment) hurrying to the west. About this time the battalion received orders from Hickey that it should dig in to bar the two roads running west and northwest from Grandménil. Deploying as rapidly as possible in the deep snow, the battalion outposted the main west road to Erezée. The Germans negotiated this forward roadblock without a fight, the ubiquitous and deceptive Sherman tank again providing the ticket. When the panzers, some eight of them, arrived at the main foxhole line the German tankers swiveled their gun turrets facing north and south to blast the battalion into two halves. One unknown soldier in Company K was undaunted by this fusillade: he held his ground and put a bazooka round into the spot but he had stopped the enemy column cold in its tracks, for here the road edged a high cliff and the remaining panzers could not pass their stricken mate. Apparently the Panther detachment [591] had outrun its infantry support or was apprehensive of a close engagement in the dark, for the German tanks backed off and returned to Grandménil. It took some time to reorganize the 3d Battalion of the 289th, but about 0800 the battalion set off on its assigned task of clearing the woods southwest of Grandménil. At the same time the rest of the regiment, on the right, moved into an attack to push the outposts of the 560th Volks Grenadier Division back from the Aisne River. General Hickey, however, needed more help than a green infantry regiment could give if the 3d Armored was to halt the 2d SS Panzer and restore the blocking position at Grandménil. His plea for assistance was carried by General Rose up the echelons of command, and finally CCB was released from attachment to the 30th Division in the La Gleize sector to give the needed armored punch. Early in the afternoon Task Force McGeorge (a company each of armored infantry and Sherman tanks) arrived west of Grandménil. The task force was moving into the attack when disaster struck. Eleven P-38's of the 430th Squadron, which were being vectored onto their targets by the 7th Armored Division, mistook McGeorge's troops for Germans and made a bombing run over the wooded assembly area. CCB later reported that 3 officers and 36 men were killed by the American bombs. Here again the failure of communications between the 3d and 7th Armored Divisions had cost dear.8 A new attack was mounted at 2000, McGeorge's armored infantry and a company from the 289th preceding the American tanks in the dark. Within an hour five tanks and a small detachment of the armored infantry in half-tracks were in Grandménil, but the enemy promptly counterattacked and restored his hold on the village. The 2d SS Panzer had nevertheless failed on 25 December to enlarge the turning radius it needed around the Grandménil pivot. The German records show clearly what had stopped the advance. Every time that the 3d Panzer Grenadier formed an assault detachment to break out through the woods south and west of Grandménil, the American artillery observers located on the high ground to the north brought salvo after salvo crashing down. All movement along the roads seemed to be a signal for the Allied fighter-bombers to swoop down for the kill.9 To make matters worse, the 9th SS Panzer had failed to close up on the 2d SS Panzer Division's right. General Lammerding dared not swing his entire division into the drive westward and thus leave an open flank facing the American armor known to be north of Manhay. Although General Ridgway had [592] ordered the 7th Armored to recapture Manhay "by dark tonight," the means at Hasbrouck's disposal on the 25th were meager. CCA, which had been employed earlier because it had come out of the St. Vith fight with the fewest wounds, now was in poor shape indeed, having lost nearly two medium tank companies and much of its tank destroyer complement. CCB had not yet been reorganized (and in any case it was very much below strength in men and vehicles) but it could furnish two understrength tank companies and one company of armored infantry. The main road into Manhay from the north, intended as the avenue of Hasbrouck's advance, would take some hours to clear, for the retreating tankers had littered it with felled trees during the night withdrawal. To get at grips with the enemy from this direction the 2d Battalion of the 424th Infantry was added to the attack; the whole operation would, or so it was hoped, mesh with the 3d Armored advance on Grandménil from the west. The abatis on the Manhay road effectively stopped the 7th Armored tanks. When a company of six tanks lined up for a charge into Manhay from the east, half of them were knocked out; General Hasbrouck, who was on the scene, ordered the remaining tanks to retire. The battalion from the 424th did succeed in nearing the village but paid a heavy toll for the few hundred yards crossed-later estimated as some 35 percent casualties-and at dark was ordered back to the north. While the 2d SS Panzer was struggling to shake itself loose for the drive west along the Erezée-Soy road, the battle-weary and depleted 560th Volks Grenadier Division fought to gain control of the western section of the same road between Soy and Hotton. Having driven a salient north in the Aisne valley, the left wing of this division set up a night attack on Christmas Eve intended to dislodge Task Force Orr from the Aisne bridgehead at Amonines. This small American task force held a three-mile front-little more than a chain of pickets-with no support on the flanks and no troops to cover its rear. When evening came, crisp and clear, the enemy guns and rocket launchers set to work. Probably the Germans used a battalion of infantry, making twelve separate attempts to break through Orr's line. At one point they were near success: Orr said later, "If they'd have had three more riflemen they'd probably have overrun our positions." But the attacker lacked the "three more riflemen" and Task Force Orr retained control of Amonines. While the enemy hammered futilely at Task Force Orr on the night of 24 December, Hogan's encircled task force far to the south at Marcouray finally made a break to reach the American lines.10 All the operable vehicles were destroyed or damaged, and the wounded were left in the charge of volunteer medical aid men. Guiding on the stars and compass, Hogan's men moved stealthily through the enemy positions. At one point a German sentry gave a challenge, but a sergeant got to him with a bayonet before he could spread the alarm. Most members of the task [593] force reached their comrades by Christmas morning. The appearance of the 75th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Fay B. Prickett) in the 3d Armored sector promised the needed rifle strength to establish a solid defense in the rugged country east of Hotton and along the bluffs of the Aisne River. To establish a homogeneous line the Americans would have to seize the high, wooded, and difficult ground south of the Soy-Hotton road, and at the same time push forward on the left to close up to the banks of the Aisne over the tortuous terrain south of the Erezée-Grandménil road. With the two regiments of the 75th attached to the 3d Armored (the 289th Infantry and the 290th Infantry), General Rose ordered a drive to cement the CCA wing in the west. The units of the 75th had been scattered in widely separated areas after their arrival in Belgium. A smooth-running supply system had not yet been set up, and to concentrate and support the rifle battalions would prove difficult. But the 290th (Col. Carl F. Duffner), which had been moving into a defensive position around Petit Han, north of Hotton, received orders at 1600 on the 24th to assemble at Ny for an attack to begin two hours later. There ensued much confusion, with orders and counter-orders, and finally the attack was rescheduled for a half-hour before midnight. The regiment had no idea of the ground over which it was to fight but did know that the line of departure was then held by a battalion or less of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment deployed along the Soy-Hotton road. The 2d and 3d Battalions of the 290th were chosen for this first battle, their objective the wooded ridge south of the road. About midnight on the 24th the battalions started their assault companies forward, crossing a small stream and ravine, then halting to reorganize at a tree line which edged a broad meadow over which the assault had to be carried. Here all was confusion and the companies were not straightened out until dawn. Finally the assault began, straight across the open, snow-covered meadow beyond which lay the ridge line objective. Losses among these green troops were severe and most of the officers were killed or wounded. Despite this harsh baptism of fire the troops reached the wood cover at the foot of the ridge and held on. In midafternoon more infantry came up (probably from the 517th), plus a platoon of tank destroyers, and a fresh assault was now organized. This carried through the woods and onto the ridge. Participants in the action later estimated that the 3d Battalion, 290th Infantry, alone suffered 250 casualties, but this figure probably is exaggerated. 11 Farther east the 289th Infantry also had a rough introduction to battle on rugged terrain far more difficult than any training ground in the States. On the night of 24 December the regiment moved by truck to Fanzel, north of Erezée, there receiving orders to attack at 0800 the next morning and seize the high ground north of the Aisne. Early on Christmas morning, as already related, the 3d Battalion was hastily thrown into the fight being waged by the 3d Armored troops west of Grandménil. By the hour set for the 289th to attack, [594] however, a part of the 3d Battalion could be freed to move into the regimental advance. The 560th Volks Grenadier Division had only a thin screen facing the 289th and by dusk the 3d Battalion was on its objective, the hill mass southwest of Grandménil. On the right flank the 1st Battalion reached the line of the Aisne, but in the center the yd Battalion lost its direction in the maze of wooded hills and ravines. By midnight of the 25th it had gravitated into and around La Fosse, a village southwest of Grandménil, leaving a wide gap between itself and the 1st Battalion. The next day, under a new commander, the 2d Battalion deployed along the Aisne but still had no contact with the 1st.12 Although the 2d SS Panzer Division still held Grandménil and Manhay on the morning of 26 December, it had lost much of its bite and dash. The two grenadier regiments had been whittled down considerably; the 4th Panzer Grenadier had lost heavily, particularly in officers, during the fight for the Baraque de Fraiture. Across the lines thirteen battalions of field artillery were firing into the German positions between the Aisne and the Lienne, and the II SS Panzer Corps had been unable to bring forward enough artillery and ammunition to engage in any counterbattery duels. So heavy was the traffic on the meager Sixth Panzer Army line of communications, and moving as it did by fits and starts under the watchful eyes of Allied air, that only one battalion of corps artillery and one corps Werfer battalion succeeded in crossing to the west bank of the Salm. Ammunition resupply from the rear was almost nonexistent. On Christmas Eve the corps had taken matters in its hands and dispatched its own trucks to the ammunition dumps back at Bonn, but each round trip would take three to four nights because the daylight movement of thin-skinned vehicles carrying high explosive was almost certain suicide. Finally, the 9th SS Panzer had failed to keep to schedule and probably would not come abreast of the 2d SS until the night of 26 December. But General Lammerding could not delay his bid for a breakout until reinforcements arrived. On the morning of the 26th he ordered the 4th Panzer Grenadier to attack northward, using Manhay and the forest to the east as a line of departure. The 3d Panzer Grenadier would have to make the main effort, forcing its way out of Grandménil and along the road west to Erezée. The enemy attempt to shake loose and break into the clear proved abortive. On the right the 4th Panzer Grenadier sent a battalion from the woods east of Manhay into an early morning attack that collided with Billingslea's glider infantry in Tri-le-Cheslaing. In the predawn darkness some of the grenadiers sneaked in on the battalion command post, only to be driven off by a reserve platoon. A move to encircle the village from the east was beaten back almost single-handedly by a stray Sherman tank [595] which the glider infantry had commandeered during the 7th Armored withdrawal. When daylight came the enemy assault force was in full retreat, back to the woods. Plans for a second attack north from Manhay died aborning, for by that time the Americans had the initiative. The German advance out of Grandménil was planned as a double-pronged assault: one column thrusting straight west on the Erezée road; the other heading off to the northwest along a narrow, precipitous road which would bring it to Mormont and a flanking position vis-à-vis Erezée. The westward move began at false dawn, by chance coinciding with Task Force McGeorge's renewal of its attack to enter Grandménil. Again the road limited the action to a head-on tank duel. McGeorge's Shermans were outgunned by the Panthers, and when the shooting died down the American detachment had only two medium tanks in going condition. Sometime after this skirmish one of the American tanks which had reached the edge of the village during the attack of the previous evening suddenly came alive and roared out to join the task force. What had happened was one of the oddities born of night fighting. Captain Jordan of the 1st Battalion, 3d Armored Regiment, had led five tanks into Grandménil, but during the earlier fight four had been hit or abandoned by their crews. Jordan and his crew sat through the night in the midst of the dead tanks, unmolested by the enemy. When the captain reported to his headquarters, he told of seeing a German column, at least twelve Panthers, rumbling out of Grandménil in a northerly direction. The 3d Armored put up a liaison plane to find the enemy tanks, but to no avail. It is known that Company L of the 289th Infantry knocked out a Panther leading a vehicular column through a narrow gorge on the Mormont road and took a number of casualties during a scrambling fight between bazookas and tank weapons. The German accounts say that this road was blocked by fallen timber and that intense American artillery fire halted all movement north of Grandménil. Whatever the reason, this group of tanks made no further effort to force the Mormont road.13 Task Force McGeorge received sixteen additional Shermans at noon and a couple of hours later, on the heels of a three-battalion artillery shoot, burst through to retake Grandménil. The pounding meted out by the 3d Armored gunners apparently drove most of the grenadiers in flight from the village; by dark the 3d Battalion of the 289th had occupied half of the village and held the road to Manhay. There remains to tell of the 7th Armored's attempt to recapture Manhay. To visualize the 7th Armored as a ready combat division at this time would be to distort reality. By the 26th its three armored infantry battalions were woefully understrength, and less than 40 percent of its tanks and tank destroyers were operable. Even this very reduced capability could not be [596]

DESTRUCTION AT GRANDMÉNIL, including a damaged German King Tiger tank. employed with full effect against the enemy. It was only a matter of hours since the 7th Armored had been driven from St. Vith, and the officers, men, and vehicles of most of its units were spread about helter-skelter from village to village just as they had arrived back in the American lines after the disorganization attendant on the withdrawal across the Salm. The problem of combat morale is more difficult for the historian, writing long after the event, to analyze. Hasbrouck's division had made a fight of it at St. Vith, more than meriting the eulogy of Field Marshal Montgomery's retreat order, "They come back in all honor"; but it was too much to expect of human flesh and blood, mind and heart, that the 7th Armored should continue, only hours after the retreat, to demonstrate the same high order of combat efficiency seen in the defense of St. Vith. General Hasbrouck had no plans for retaking Manhay on the morning of the 26th; he counted rather on a few hours to regroup his command. But about 0900 General Collins called from the VII Corps to ask that Ridgway put the 7th Armored into an attack at Manhay as an assist for the 3d Armored drive against the twin village of Grandménil. [597] Within the hour the First Army Commander had General Ridgway on the telephone, insisting that the 7th Armored must attack-and that forthwith. Ridgway could do no more than tell Hasbrouck to retake Manhay "as soon as possible." The 7th Armored commander put the few tanks he could scrape together into a march toward the road linking Manhay and Grandménil, but this move was slow in starting and the 3d Armored troops entered Grandménil while the 7th Armored tanks still were several hundred yards to the north. About this time the 7th Armored detachment came under accurate direct fire from some German tanks dug in north of the connecting road and the Americans halted. Meanwhile Allied fighter-bombers had been vectored over Manhay to soften up the defenders, and General Ridgway decided to use the fresh 3d Battalion of the 517th Parachute Infantry, which had just come down from helping the 30th Division in the La Gleize operation, for a night assault at Manhay. This attack, made an hour or so after midnight and preceded by an eight-battalion artillery concentration fired for twenty minutes, gained quick success. By 0400 on 27 December the paratroopers had cleared the village, at a cost of ten killed and fourteen wounded. By dawn airborne engineers had cleared the fallen trees from the road back to Werbomont, and a platoon of medium tanks moved in to cover the approaches to the village. Some clue to the ease with which the paratroopers took Manhay-not forgetting, of course, the weight of metal thrown into the town by the American cannoneers-may be found in the German account of events on the 26th. It would appear that the 7th Armored tank detachment which had neared the Grandménil-Manhay road had convinced the commander of the 3d Panzer Grenadier that his battalion in Manhay was in danger of being surrounded (particularly since Billingslea's paratroopers to the east had driven back the 4th Grenadiers) and that he had ordered the Manhay garrison to withdraw under cover of night, leaving its wounded behind. The loss of Manhay ended the 2d SS Panzer battle in this sector, and the German corps and division commanders agreed that there seemed little chance of starting the attack rolling again. On the morning of the 27th orders from Sepp Dietrich told General Lammerding that his division would be relieved by the 9th SS Panzer Division and that the 2d SS Panzer would move west to join the 560th Volks Grenadier Division and the newly arrived 12th SS Panzer Division in a new Sixth Panzer Army attack directed at the Hotton-Soy-Erezée line. The 82d Airborne Withdraws From the Salm River Line When the XVIII Airborne Corps commander ordered the defense of St. Vith abandoned on 23 December, one of his chief concerns was the mounting enemy strength which threatened to outflank and overrun the small detachments of the 82d Airborne Division, plus the 3d Battalion, 112th Infantry, deployed to hold the bridgeheads at Salmchâteau and Vielsalm through which the St. Vith garrison had to withdraw. The 82d, it will be remembered, was forced to hurry troops from its north flank, where they had been involved in [598] hard battle with the 1st SS Panzer Division around Trois Ponts and Cheneux, in order to reinforce the opposite flank of the division, which extended from Salmchâteau west to Fraiture, at Fraiture dangling in the air. The danger now was that the German armor already on the west side of the Salm River would speed to turn this open flank and crush the 82d Airborne back against the Salm, or at the least-make a powerful jab straight along the west bank to dislodge the American hold on the two bridgehead towns. Kampfgruppe Krag, as already recounted, did succeed in doing exactly that at Salmchâteau late on the 23d and entrapped part of Task Force Jones and the last column of the 112th Infantry on their way back from St. Vith. The 9th SS Panzer Division, charged in the enemy scheme with breaking across the river at Salmchâteau and Vielsalm and here rolling up the 82d Airborne south wing, failed to arrive at the Salm on schedule. As a result General Gavin was faced with one major threat against his position, on the night of 23 December posed by the 2d SS Panzer and the Fuehrer Begleit Brigade at Fraiture, rather than two as the II SS Panzer Corps had hoped. By midday on the 24th, however, the Germans had patrols across the river at Vielsalm. This covering force came from the 19th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, recruited from Germans living in the Black Sea area, and it had earned a reputation as the elite regiment of the 9th SS Panzer Division. The rest of the 9th SS Panzer either had been detached on other missions or was straggling to the east-indeed, the divisional tank regiment did not reach the Salm sector until the first days of January. American identification of this new armored division, however, added to the list of factors that resulted in the decision to withdraw the 82d Airborne and shorten the XVIII Airborne Corps line. Early on Christmas Eve General Gavin met with some of his officers in the command post of Ekman's 505th. He knew that his division was faced by elements of at least three German divisions, his right was overextended, the support which might be expected from his right wing neighbor was problematical, and a large German force (the remnants of Kampfgruppe Peiper) was actually in his rear somewhere near Trois Ponts. Gavin now had to decide whether he should divert some of his troops to hunt out and fight the enemy in his rear or proceed with the planned withdrawal. The main problem, Gavin concluded, was to put his division in an organized position, dug in with wire and mines in place, to confront the attack of "several" panzer divisions on the morning of the 25th. He held, then, to his plan for withdrawing the 82d Airborne.14 Gavin's plan was to bring back the bulk of his regiments under cover of night; he would leave small detachments from each as covering shells until the early morning. About 2100 the division moved out for the new Trois Ponts-Manhay line. Christmas Eve was crystal clear and the moonlight on the [599] snow made it easy to follow the routes assigned. (Overhead the buzzbombs could be traced on their flight to Antwerp.) At only two points did the enemy interfere with the marching columns of the 82d Airborne, and at only one of these by design. After the debacle at La Gleize, Colonel Peiper and some 800 of his kampfgruppe had taken refuge in the densely wooded and broken ground north of Trois Ponts, waiting for an opportunity to cross the Salm and rejoin their comrades of the 1st SS Panzer. The hour chosen by Peiper coincided with the move made by the 50th Parachute Infantry as it pivoted on Trois Ponts back from the river. The two forces, both attempting to withdraw, brushed against each other and one company of the 505th got into a brief but hot fire with Peiper's men. Colonel Ekman, however, had a mission to complete before day dawned and with General Gavin's permission the 505th let Peiper go. The second action this night was no accident. It involved the covering force of the 508th, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Shanley, in what the regiment later recorded as "one of the best pieces of fighting in the 508th's history." The main body started on the seven-mile trek to its new line with no sign of the enemy and by 0415 was in position. Some time around midnight the covering platoons near the Vielsalm bridge site (one each from Companies A and B) heard much noise and hammering coming from the direction of the bridge, which the airborne engineers had partially demolished. Suddenly artillery and mortar shells erupted around the American foxhole line, a barrage followed by smoke shells. Out of the smoke rose dark figures, whooping and yelling as they charged the paratroopers. The platoon from Company B had a few moments to get set and then stopped the grenadiers with machine gun fire before they could reach the position. The Company A platoon, closer to the river's edge, had a worse time of it. Here a few of the enemy got into the American position, while others blocked the withdrawal route to the west. At one point the 508th wrote this platoon off as lost; but skillfully led by 1st Lt. George D. Lamm the paratroopers fought their way through the enemy and back to their own lines. The 19th Regiment, which had hit the paratroopers at Vielsalm, followed the American spoor doggedly, despite the laggard pace of the rest of the division, and in the early afternoon of 25 December was observed in Odrimont, a couple of miles from the 508th outpost line. That night the 19th hit the regimental left, with perhaps two battalions making the assault, but was beaten back after a three-hour fire fight. Two nights later the 19th struck again, this time driving on a narrow front against the right wing of the 508th. Company G was driven out of the twin villages of Erria and Villettes where it was bivouacked, but this penetration came to an abrupt halt when two artillery battalions went to work. The following morning the commander of the 3d Battalion (Lt. Col. Louis G. Mendez) organized a counterattack which swept through Erria (catching a number of the tired grenadiers still asleep in captured bedrolls) and restored the line. The American gunners had done much to take the sting out of the enemy force over 100 German dead were counted [600] around the village crossroad (the German account relates that the 1st Battalion of the 19th was "cut to pieces" here). As the year came to a close the Sixth Panzer Army made one last effort to breach the American defenses between the Salm and the Ourthe. This battle took place in and around the hamlet of Sadzot (so tiny that it does not appear on most of the Belgian maps). Sadzot lay on a small creek 400 yards south of Briscol, a village on the main road between Grandménil and Erezée. The engagement at Sadzot was fought by squads and platoons, and so may be appropriately called a "soldiers' battle"; with equal propriety the name coined by the GI's for this confused action is used here: "The Sad Sack Affair." 15 Having given up the fight for Manhay and Grandménil, the 2d SS Panzer began to parcel out its troops. Some were left to cover the deployment of the 9th SS Panzer as it extended its position in front of the 82d Airborne to take over the onetime 2d SS Panzer sector. Other units shifted west to join the incoming 12th SS Panzer in what was planned as a major attack to cross the Trois Ponts-Hotton road in the vicinity of Erezée and regain momentum for the drive to the northwest. Once again, however, the forces actually available to the II SS Panzer Corps were considerably fewer than planned. The march west by the 12th SS Panzer Division had taken much longer than reckoned, for the slow-moving 9th SS Panzer had jammed the roads in front of the 12th SS Panzer, there had been a series of fuel failures, Allied air attacks had cut most of the march to night movement, and just as the division was nearing the Aisne River OB WEST had seized the rearward columns for use at Bastogne. All that the 12th SS Panzer could employ on 27 December, the date set by the army commander for the new attack, was the 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, most of which was already in the line facing the 3d Armored. The 2d SS Panzer contribution perforce was limited: its reconnaissance battalion, a battalion of mobile guns, and two rifle companies, a task force commanded by the same Major Krag who had raised such havoc at Salmchâteau. The time for the attack was midnight. During the 27th the lines of General Hickey's command had been redressed. In the process the 1st Battalion of the 289th Infantry had tied in with Task Force Orr on the Aisne River while the 2d Battalion, having finally straightened itself out, continued the 3d Armored line through the woods southwest of Grandménil. Unknown at the time, a 1,000 yard gap had developed south of Sadzot and Briscol between these two battalions. At zero hour the German assault force started forward through the deep woods; the night was dark, the ground pathless, steep, and broken. The grenadiers made good progress, but radio failed in the thick woods and it would appear that a part of the attackers became disoriented. At least two companies [601] from the 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment did manage to find their way through the gap between the battalions of the 289th and followed the creek into Sadzot, where they struck about two hours after the jump-off. The course of battle as it developed in the early morning hours of 28 December is extremely confused. The first report of the German appearance in Sadzot was relayed to higher headquarters at 0200 by artillery observers belonging to the 24th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, whose howitzers were emplaced north of the village. The two American rifle battalions, when queried, reported no sign of the enemy. Inside Sadzot were bivouacked Company C of the 87th Chemical Battalion and a tank destroyer platoon; these troops rapidly recovered from their surprise and during the melee established a firm hold on the north side of the village. General Hickey immediately alerted the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion near Erezée to make an envelopment of Sadzot from west and east, but no sooner had the paratroopers deployed than they ran into Krag's kampfgruppe. This meeting engagement in the darkness seems to have been a catch-as-catch-can affair. The American radios, like the German, failed to function in this terrain (the 3d Armored communications throughout the battle were mostly by wire and runner); the Germans were confused and put mortar fire on their own neighboring platoons; and the fight on both sides was carried by squads and platoons firing at whatever moved. When daylight came the paratroopers got artillery support, which far outweighed the single battalion behind the enemy assault force, and moved forward. By 1100 the 509th had clicked the trap shut on the Germans inside Sadzot. There remained the task of closing the gap between the two battalions of the 289th. General Hickey put in the 2d Battalion of the 112th Infantry at dark on the 28th, but this outfit, hastily summoned to the fight, lost its direction and failed to seal the gap. Early on the morning of the 29th Hickey, believing that the 112th had made the line of departure secure, sent the 509th and six light tanks to attack toward the southeast. But the enemy had reorganized in the meantime, put in what probably was a fresh battalion, and begun a new march on Sadzot. In the collision that followed, a section of German 75-mm. antitank guns destroyed three of the light tanks and the paratroopers recoiled; but so did the enemy. During the morning the 2d Battalion, 112th Infantry, got its bearings-or so it was believed-and set out to push a bar across the corridor from the west, where contact with the 1st Battalion of the 289th was firm, to the east and the socket provided the 2d Battalion, 289th. Across the deep ravines and rugged hills American troops were sighted, and believing these to be the 2d Battalion the troops from the 112th veered toward them. What had been seen, however, proved to be the paratroopers of the 509th. After this misadventure and the jolt suffered by the paratroopers, Hickey and the battalion commanders concerned worked out a coordinated attack. First the paratroopers put in a twilight assault which forced the Germans back. Then the 2d Battalion of the 112th made a night attack with marching fire, guiding this time on 60-mm. illuminating [602] mortar shells fired by the 2d Battalion of the 289th. Crossing through deep ravines the infantrymen of the 112th drove the enemy from their path. At dawn on the 29th the gap finally was closed. The German failure to penetrate through the Erezée section on 28-29 December was the last serious bid by the Sixth Panzer Army in an offensive role. On that day Field Marshal Model ordered Sepp Dietrich to go over to the defensive and began stripping the Sixth of its armor. The German commanders left facing the VII and XVIII Airborne Corps east of the Ourthe record a number of attacks ordered between 29 December and 2 January, the units involved including infantry detachments from the 9th SS Panzer Division and the 18th and 62d Volks Grenadier Divisions. But to order these weak and tired units into the attack when the German foot soldier knew that the great offensive was ended was one thing, to press the assault itself was quite another. The American divisions in this sector note only at the turn of the year: front quiet," or "routine patrolling." The initiative had clearly passed to the Americans. General Ridgway, who had been champing at the bit to go over to the offensive even when his corps was not hard pressed, sought permission to start an attack on the last day of the year with the XVIII Airborne, but Field Marshal Montgomery already had decided that the Allied offensive on the north flank would be initiated farther to the west by Collins' corps and had set the date-3 January 1945. The four infantry divisions of the V Corps by 24 December formed a firm barrier along the northern shoulder of the deepening German salient. This front, extending from Monschau to Waimes, relapsed into relative inactivity. The Sixth Panzer Army had tried to widen the road west by levering at the American linchpin in the Monschau area, by cutting toward the Elsenborn Ridge via Krinkelt-Rocherath, and by chopping at Butgenbach in an attempt to roll back the V Corps' west flank, but the entire effort had been fruitless and its cost dear. Having failed to free the right wing of the Sixth Panzer Army, the higher German commands gave the ball to the Fifth Panzer Army and perforce accepted the narrow zone of advance in the Sixth Panzer Army sector which gave two instead of the originally scheduled four main roads for its drive west. Be it added that the northernmost of the two remaining roads was under American artillery fire for most of its length. It cannot be said that the Sixth Panzer Army clearly had written off the possibility of overrunning the Elsenborn Ridge. The attacks by the German right wing had dwindled away by 24 December because of sheer fatigue, heavy losses, the withdrawal of most of the German armor, the feeling on the part of the army staff that it would be best to wait for further successes in the south before going out on a limb, and the desire to withhold sufficient strength to meet any American counterattack directed from the Elsenborn area against the shoulder of the salient. Furthermore, on 24 or 25 December, Hitler dropped the plan for the secondary attack by the Fifteenth Army toward Maastricht and Heerlen, which had been intended to assist the Sixth Panzer drive after the [603] latter got rolling. But there still were five German divisions in this sector under Hitzfeld's LXVII Corps, the corps maintaining a front whose boundaries coincided almost exactly with those of the American V Corps. These could be no further thought of a drive to Eupen and the establishment of a blocking cordon west of that point; this mission had been scrubbed when the last attacks at Monschau collapsed. Nor was there hope that the right wing of the Sixth Panzer Army could be set in motion at this date, the armor already having been shifted to beef up the advance on the left. Hitzfeld's task was to defend, to hold the shoulder; but his line, bent in a sharp right angle near Wirtzfeld, was expensive in manpower and tactically poor. On Model's order Hitzfeld and his division commanders ran a map exercise on 26 December whose solution was this; the angle at Wirtzfeld must be straightened and the line shortened. The powerful groupment of American artillery on Elsenborn Ridge constituted an ever-present threat; therefore this ground should be taken. Four divisions, it was planned, would attack to achieve this solution. Meanwhile the main German advance was having trouble. The Bastogne road center continued in American hands, greatly hampering the development of the Fifth Panzer Army attack. The forward wing of the Sixth Panzer Army had collided with the American defenses along the line of the Amblève and Salm Rivers but had failed to gain maneuver room and was proceeding on a dangerously narrow front. Every mobile or semimobile unit which could be found would have to be thrown into the main advance. The Army Group B commander, acting on Hitler's order, took the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division out of the LXVII Corps and told Hitzfeld to abandon his planned attack against the strong Elsenborn Ridge position. The corps was left a limited task, to iron out the Wirtzfeld angle. Finally, on 28 December, Hitzfeld was ready, but his assault force now represented only parts of two divisions, the 12th Volks Grenadier Division and the 246th. Early that morning two battalions of the 352d Regiment (246th Volks Grenadier Division) moved out of the woods near Rocherath against the forward lines of the 99th Infantry Division on the Elsenborn Ridge. This attack was blown to pieces by accurate shelling from the batteries on the ridge. A battalion of the 48th Regiment (12th Volks Grenadier Division) met an identical fate when it started toward the 2d Infantry Division position northwest of Wirtzfeld. Two battalions from the 27th Regiment (12th Volks Grenadier Division) took a crack at the 1st Infantry Division front in the Butgenbach sector, but intense rocket fire and shellfire failed to shake the defenders and left their supporting artillery unscathed. The German assault battalions had not even deployed from approach march formation when a rain of bursting shells scattered them in every direction. A handful of riflemen and engineers reached a draw leading to the American foxhole line only to be captured or driven off. This was the last attack against the American forces arrayed on the north shoulder. Hitzfeld was left to hold what he could of his lengthy front with a force which by the close of December had dwindled to [604] three understrength divisions. The German High Command and the troops of the Sixth Panzer Army now waited apprehensively and hopelessly for the retaliatory blow to fall. That the American attack would come in a matter of hours or a very few days was clear to all. Where it would be delivered along the length of the north flank of the Ardennes salient was a good deal less certain. A few of the German leaders seem to have anticipated originally that the Allied counterattack would come from north and south against the base of the salient, but by the end of December intelligence reports definitely ruled out any Allied build-up at the shoulders of the salient. The Sixth Panzer Army staff, acutely aware of the weakened condition of the German troops in the Malmédy sector, was apprehensive that the Allied effort would be made there in a drive through to St. Vith, and set two ordnance companies scrambling to recreate a single operational tank company from the armored debris the 1st SS Panzer Division had brought out of the La Gleize debacle. What Rundstedt and Model expected of their adversary can never be known, although their respective staffs seem to have read into Patton's battle around Bastogne a strong indication that the poised Allied pincers would close somewhere in the vicinity of Houffalize. It is known, however, how Rundstedt regarded the Allied strategy which on 3 January sent the American divisions attacking from north and south to snip off the tip of the salient at Houffalize: this was, says the OB WEST War Diary, "the small solution."

[605]

|