CHAPTER I The Origins On Saturday, 16 September 1944, the daily Fuehrer Conference convened in the Wolf's Lair, Hitler's East Prussian headquarters. No special word had come in from the battle fronts and the briefing soon ended, the conference disbanding to make way for a session between Hitler and members of what had become his household military staff. Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl were in this second conference. So was Heinz Guderian, who as acting chief of staff for OKH held direct military responsibility for the conduct of operations on the Russian front. Herman Goering was absent. From this fact stems the limited knowledge available of the initial appearance of the idea which would be translated into historical fact as the Ardennes counteroffensive or Battle of the Bulge. Goering and the Luftwaffe were represented by Werner Kreipe, chief of staff for OKL. Perhaps Kreipe had been instructed by Goering to report fully on all that Hitler might say; perhaps Kreipe was a habitual diary-keeper. In any case he had consistently violated the Fuehrer ordinance that no notes of the daily conferences should be retained except the official transcript made by Hitler's own stenographic staff. Trenchant, almost cryptic, Kreipe's notes outline the scene. Jodl, representing OKW and thus the headquarters responsible for managing the war on the Western Front, began the briefing.1 In a quiet voice and with the usual adroit use of phrases designed to lessen the impact of information which the Fuehrer might find distasteful, Jodl reviewed the relative strength of the opposing forces. The Western Allies possessed 96 divisions at or near the front; these were faced by 55 German divisions. An estimated 10 Allied divisions were en route from the United Kingdom to the battle zone. Allied airborne units still remained in England (some of these would make a dramatic appearance the very next day at Arnhem and Nijmegen). Jodl added a few words about shortages on the German side, shortages in tanks, heavy weapons, and ammunition. This was a persistent and unpopular topic; Jodl must have slid quickly to the next item-a report on the German forces withdrawing from southern and southwestern France. Suddenly Hitler cut Jodl short. There ensued a few minutes of strained silence. Then Hitler spoke, his words recalled as faithfully as may be by the listening [1] ADOLF HITLER OKL chief of staff. "I have just made a momentous decision. I shall go over to the counterattack, that is to say"-and he pointed to the map unrolled on the desk before him-"here, out of the Ardennes, with the objective-Antwerp." While his audience sat in stunned silence, the Fuehrer began to outline his plan. Historical hindsight may give the impression that only a leader finally bereft of sanity could, in mid-September of 1944, believe Germany physically capable of delivering one more powerful and telling blow. Politically the Third Reich stood deserted and friendless. Fascist Italy and the once powerful Axis were finished. Japan had politely suggested that Germany should start peace negotiations with the Soviets. In southern Europe, as the month of August closed, the Rumanians and Bulgarians had hastened to switch sides and join the victorious Russians. Finland had broken with Germany on 2 September. Hungary and the ephemeral Croat "state" continued in dubious battle beside Germany, held in place by German divisions in the line and German garrisons in their respective capitals. But the twenty nominal Hungarian divisions and an equivalent number of Croatian brigades were in effect canceled by the two Rumanian armies which had joined the Russians. The defection of Rumanian, Bulgarian, and Finnish forces was far less important than the terrific losses suffered by the German armies themselves in the summer of 1944. On the Eastern and Western Fronts the combined German losses during June, July, and August had totaled at least 1,200,000 dead, wounded, and missing. The rapid Allied advances in the west had cooped up an additional 230,000 troops in positions from which they would emerge only to surrender. Losses in matériel were in keeping with those in fighting manpower. Room for maneuver had been whittled away at a fantastically rapid rate. On the Eastern Front the Soviet summer offensive had carried to the borders of East Prussia, across the Vistula at a number of points, and up to the northern Carpathians. Only a small slice of Rumania was left to German troops. By mid-September the German occupation forces in southern Greece and the Greek islands (except Crete) already were withdrawing as the German grasp on the Balkans weakened. On the Western Front the Americans had, in the second week of September, [2] put troops on the soil of the Third Reich, in the Aachen sector, while the British had entered Holland. The German armies in the west faced a containing Allied front reaching from the Swiss border to the North Sea. On 14 September the newly appointed German commander in the west, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, acknowledged that the "Battle for the "West Wall" had begun. On the Italian front Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring's two armies retained position astride the Apennines and, from the Gothic Line, defended northern Italy. Here, of all the active fronts, the German forces faced the enemy on something like equal terms-except in the air. Nonetheless the Allies were dangerously close to the southern entrances to the Po Valley. In the far north the defection of Finland had introduced a bizarre operational situation. In northern Finland and on the Murmansk front nine German divisions held what earlier had been the left wing of the 700-mile Finno-German front. Now the Finns no longer were allies, but neither were they ready to turn their arms against Generaloberst Dr. Lothar Rendulic and his nine German divisions. The Soviets likewise showed no great interest in conducting a full-scale campaign in the subarctic. With Finland out of the war, however, the German troops had no worthwhile mission remaining except to stand guard over the Petsamo nickel mines. Only a month after Mannerheim took Finland out of the war, Hitler would order the evacuation of that country and of northern Norway. Political and military reverses so severe as those sustained by the Third Reich in the summer of 1944 necessarily implied severe economic losses to a state and a war machine fed and grown strong on the proceeds of conquest. Rumanian oil, Finnish and Norwegian nickel, copper, and molybdenum, Swedish high-grade iron ore, Russian manganese, French bauxite, Yugoslavian copper, and Spanish mercury were either lost to the enemy or denied by the neutrals who saw the tide of war turning against a once powerful customer. Hitler's Perspective September 1944 In retrospect, the German position after the summer reverses of 1944 seemed indeed hopeless and the only rational release a quick peace on the best possible terms. But the contemporary scene as viewed from Hitler's headquarters in September 1944, while hardly roseate, even to the Fuehrer, was not an unrelieved picture of despair and gloom. In the west what had been an Allied advance of astounding speed had decelerated as rapidly, the long Allied supply lines, reaching clear back to the English Channel and the Côte d'Azur, acting as a tether which could be stretched only so far. The famous West Wall fortifications (almost dismantled in the years since 1940) had not yet been heavily engaged by the attacker, while to the rear lay the great moat which historically had separated the German people from their enemies-the Rhine. On the Eastern Front the seasonal surge of battle was beginning to ebb, the Soviet summer offensive seemed to have run its course, and despite continuing battle on the flanks the center had relapsed into an uneasy calm. [3] Even the overwhelming superiority which the Western Allies possessed in the air had failed thus far to bring the Third Reich groveling to its knees as so many proponents of the air arm had predicted. In September the British and Americans could mount a daily bomber attack of over 5,000 planes, but the German will to resist and the means of resistance, so far as then could be measured, remained quite sufficient for a continuation of the war.

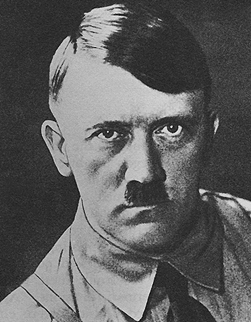

Great, gaping wounds, where the Allied bombers had struck, disfigured most of the larger German cities west of the Elbe, but German discipline and a reasonably efficient warning and shelter system had reduced the daily loss of life to what the German people themselves would reckon as "acceptable." If anything, the lesson of London was being repeated, the noncombatant will to resist hardening under the continuous blows from the air and forged still harder by the Allied announcements of an unconditional surrender policy. The material means available to the armed forces of the Third Reich appeared relatively unaffected by the ceaseless hammering from the air. It is true that the German war economy was not geared to meet a long-drawn war of attrition. But Reich Minister Albert Speer and his cohorts had been given over two years to rationalize, reorganize, disperse, and expand the German economy before the intense Allied air efforts of 1944. So successful was Speer's program and so industrious were the labors of the home front that the race between Allied destruction and German construction (or reconstruction) was being run neck and neck in the third quarter of 1944, the period, that is, during which Hitler instituted the far-reaching military plans eventuating in the Ardennes counteroffensive. The ball-bearing and aircraft industries, major Allied air targets during the first half of 1944, had taken heavy punishment but had come back with amazing speed. By September bearing production was very nearly what it had been just before the dubious honor of nomination as top-priority target for the Allied bombing effort. The production of single-engine fighters had risen from 1,016 in February to a high point of 3,031 such aircraft in September. The Allied strategic attack leveled at the synthetic oil industry, however, showed more immediate results, as reflected in the charts which Speer put before Hitler. For aviation gasoline, motor gasoline, and diesel oil, the production curve dipped sharply downward and lingered far below monthly consumption figures despite the radical drop in fuel consumption in the summer of 1944. Ammunition production likewise had declined markedly under the air campaign against the synthetic oil industry, in this case the synthetic nitrogen procedures. In September the German armed forces were firing some 70,000 tons of explosives, while production amounted to only half that figure. Shells and casings were still unaffected except for special items which required the ferroalloys hitherto procured from the Soviet Union, France, and the Balkans. Although in the later summer of 1944 the Allied air forces turned their bombs against German armored vehicle production (an appetizing target because of the limited number of final assembly plants), an average of 1,500 tanks and [4] assault guns were being shipped to the battle front every thirty days. During the first ten months of 1944 the Army Ordnance Directorate accepted 45,917 trucks, but truck losses during the same period numbered 117,719. The German automotive industry had pushed the production of trucks up to an average of 9,000 per month, but in September production began to drop off, a not too important recession in view of the looming motor fuel crisis.

The German railway system had been under sporadic air attacks for years but was still viable. Troops could be shuttled from one fighting front to another with only very moderate and occasional delays; raw materials and finished military goods had little waste time in rail transport. In mid-August the weekly car loadings by the Reichsbahn hit a top figure of 899,091 cars. In September Hitler had no reason to doubt, if he bothered to contemplate the transport needed for a great counteroffensive, that the rich and flexible German railroad and canal complex would prove sufficient to the task ahead and could successfully resist even a coordinated and systematic air attack-as yet, of course, untried. In German war production the third quarter of 1944 witnessed an interesting conjuncture, one readily susceptible to misinterpretation by Hitler and Speer or by Allied airmen and intelligence. On the one hand German production was, with the major exceptions of the oil and aircraft industries, at the peak output of the war; on the other hand the Allied air effort against the German means of war making was approaching a peak in terms of tons of bombs and the number of planes which could be launched against the Third Reich.2 But without the means of predicting what damage the Allied air effort could and would inflict if extrapolated three or six months into the future, and certainly without any advisers willing so to predict, Hitler might reason that German production and transport, if wisely husbanded and rigidly controlled, could support a major attack before the close of 1944. Indeed, only a fortnight prior to the briefing of 16 September Minister Speer had assured Hitler that German war stocks could be expected to last through 1945. Similarly, in the headquarters of the Western Allies it was easy and natural to assume the thousands of tons of bombs dropped on Germany must inevitably have weakened the vital sections of the German war economy to a point where collapse was imminent and likely to come before the end of 1944. Hitler's optimism and miscalculation, then, resulted in the belief that Germany had the material means to launch and maintain a great counteroffensive, a belief nurtured by many of his trusted aides. Conversely, the miscalculation of the Western Allies as to the destruction [5] wrought by their bombers contributed greatly to the pervasive optimism which would make it difficult, if not impossible, for Allied commanders and intelligence agencies to believe or perceive that Germany still retained the material muscle for a mighty blow. Assuming that the Third Reich possessed the material means for a quick transition from the defensive to the offensive, could Hitler and his entourage rely on the morale of the German nation and its fighting forces in this sixth year of the war? The five years which had elapsed since the invasion of Poland had taken heavy toll of the best physical specimens of the Reich. The irreplaceable loss in military manpower (the dead, missing, those demobilized because of disability or because of extreme family hardship) amounted to 3,266,686 men and 92,811 officers as of 1 September 1944.3 Even without an accurate measure of the cumulative losses suffered by the civilian population, or of the dwellings destroyed, it is evident that the German home front was suffering directly and heavily from enemy action, despite the fact that the Americans and British were unable to get together on an air campaign designed to destroy the will of the German nation. Treason (as the Nazis saw it) had reared its ugly head in the abortive Putsch of July 1944, and the skeins of this plot against the person of the Fuehrer still were unraveling in the torture chambers of the Gestapo. Had the Nazi Reich reached a point in its career like that which German history recorded in the collapse of the German Empire during the last months of the 1914-1918 struggle? Hitler, always prompt to parade his personal experiences as a Frontsoldat in the Great War and to quote this period of his life as testimony refuting opinions offered by his generals, was keenly aware of the moral disintegration of the German people and the armies in 1918. Nazi propaganda had made the "stab in the back" (the theory that Germany had not been defeated in 1918 on the battlefield but had collapsed as a result of treason and weakness on the home front) an article of German faith, with the Fuehrer its leading proponent. Whatever soul-searching Hitler may have experienced privately as a result of the attempt on his life and the precipitate retreats of his armies, there is no outward evidence that he saw in these events any kinship to those of 1918. He had great faith in the German people and in their devotion to himself as Leader, a faith both mystic and cynical. The noise of street demonstrations directed against himself or his regime had not once, during the years of war, assailed his ears. German troops had won great victories in the past, why should they not triumph again? The great defeats had been, so Hitler's intuition told him, the fruit of treason among high officers or, at the least, the result of insufficient devotion to National Socialism in the hearts and minds of the defeated commanders and the once powerful General Staff. The assassination attempt, as seen through Hitler's own eyes, was proof positive that the suspicions which he had long entertained vis-à-vis the [6] Army General Staff were correct. Now, he believed, this malignant growth could be cut away; exposure showed that it had no deep roots and had not contaminated either the fighting troops or the rank and file of the German people. Despite the heavy losses suffered by the Wehrmacht in the past five years, Hitler was certain that replacements could be found and new divisions created. His intuition told him that too many officers and men had gravitated into headquarters staffs, administrative and security services. He was enraged by the growing disparity in the troop lists between "ration strength" and "combat strength" and, as a military dictator, expected that the issuance of threatening orders and the appointment of the brutal Heinrich Himmler as chief of the Replacement Army would eventually reverse this trend. At the beginning of September Hitler was impatiently stamping the ground and waiting for the new battalions to spring forth. The months of July and August had produced eighteen new divisions, ten panzer brigades and nearly a hundred separate infantry battalions. Now twenty-five new divisions, about a thousand artillery pieces, and a score of general headquarters brigades of various types were demanded for delivery in October and November. How had Germany solved the manpower problem? From a population of some eighty million, in the Greater Reich, the Wehrmacht carried a total of 10,165,303 officers and men on its rosters at the beginning of September 1944. What part of this total was paper strength is impossible to say; certainly the personnel systems in the German armed forces had not been able to keep an accurate accounting of the tremendous losses suffered in the summer of 1944. Nonetheless, this was the strength figuratively paraded before Hitler by his adjutants. The number of units in the Wehrmacht order of battle was impressive (despite such wholesale losses as the twenty-seven divisions engulfed during the Russian summer offensive against Army Group Center). The collective German ground forces at the beginning of September 1944 numbered 327 divisions and brigades, of which 31 divisions and 13 brigades were armored. Again it must be noted that many of these units no longer in truth had the combat strength of either division or brigade (some had only their headquarters staff), but again, in Hitler's eyes, this order of battle represented fighting units capable of employment. Such contradiction as came from the generals commanding the paper-thin formations, some of whom privately regarded the once formidable Wehrmacht as a "paper tiger," would be brushed angrily aside as evidence of incompetence, defeatism-or treason. But the maintenance of this formidable array of divisions and brigades reflected the very real military potential of the Greater Reich, not yet fully exploited even at the end of five years of what had been called total war. As in 1915 the Germans had found that in a long conflict the hospitals provided a constant flow of replacements, and that this source could be utilized very effectively by the simple expedient of progressively lowering the physical standards required for front-line duty. In addition, each year brought a new class to the colors as German youth matured. This source could be further exploited by lowering the age limit at one end of the conscription spectrum while increasing it [7] at the other. In 1944, for example, the age limit for "volunteers" for the ranks was dropped to sixteen years and party pressure applied conducive to volunteering. At the same time the older conscription classes were combed through and, in 1944, registration was carried back to include males born in 1884. Another and extremely important manpower acquisition, made for the first time on any scale in the late summer of 1944, came from the Navy and Air Force. Neither of these establishments remained in any position, at this stage of the war, to justify the relatively large numbers still carried on their rosters. While it is true that transferring air force ground crews to rifle companies would not change the numerical strength of the armed forces by jot or tittle, such practice would produce new infantry or armored divisions bearing new and, in most cases, high numbers. In spite of party propaganda that the Third Reich was full mobilized behind the Fuehrer and notwithstanding the constant and slavish mouthing of the phrase "total war," Germany had not in five years of struggle, completely utilized its manpower-and equally important, womanpower-in prosecuting the war.4 Approximately four million public servants and individuals deferred from military service for other reasons constituted a reserve as yet hardly touched. And, despite claims to the contrary, no thorough or rational scheme had been adopted to comb all able-bodied men out of the factories and from the fields for service in uniform. In five years only a million German men and women had been mobilized for the labor force. Indeed, it may be concluded that the bulk of industrial and agrarian replacements for men drafted into the armed services was supplied by some seven million foreign workers and prisoners of war slaving for the conqueror. Hitler hoped to lay his hands on those of his faithful followers who thus far had escaped the rigors of the soldier life by enfolding themselves in the uniform of the party functionary. The task of defining the nonessential and making the new order palatable was given to Reich Minister Joseph Goebbels, who on 24 August 1944 announced the new mobilization scheme: schools and theaters to be closed down, a 60-hour week to be introduced and holidays temporarily abolished, most types of publications to be suspended (with the notable exception of "standard political works," Mein Kampf, for one), small shops of many types to be closed, the staffs of governmental bureaus to be denuded, and similar belt tightening. By 1 September this drastic comb-out was in full swing and accompanied within the uniformed forces by measures designed to reduce the headquarters staffs and shake loose the "rear area swine," in the Fuehrer's contemptuous phrase.5 This new flow of manpower would give Hitler the comforting illusion of combat strength, an illusion risen from his indulgence in what may be identified to the American reader as "the numbers [8] racket." Dozens of German officers who at one time or another had reason to observe the Fuehrer at work have commented on his obsession with numbers and his implicit faith in statistics no matter how murky the sources from which they came or how misleading when translated into fact. So Hitler had insisted on the creation of new formations with new numbers attached thereto, rather than bringing back to full combat strength those units which had been bled white in battle. Thus the German order of battle distended in the autumn of 1944, bloated by new units while the strength of the German ground forces declined. In the same manner Hitler accepted the monthly production goals set for the armored vehicle producers by Speer's staff as being identical with the number of tanks and assault guns which in fact would reach the front lines. Bemused by numbers on paper and surrounded by a staff which had little or no combat experience and by now was perfectly housebroken-never introducing unpleasant questions as to what these numbers really meant-Hitler still saw himself as the Feldherr, with the men and the tanks and the guns required to wrest the initiative from the encircling enemy. The plan for the Ardennes counteroffensive was born in the mind and will of Hitler the Feldherr. Its conception and growth from ovum are worthy of study by the historian and the student of the military art as a prime example of the role which may be played by the single man and the single mind in the conduct of modern war and the direction of an army numbered in the millions. Such was the military, political, economic, and moral position of the Third Reich in the autumn of 1944 that a leader who lacked all of the facts and who by nature clung to a mystic confidence in his star might rationally conclude that defeat could be postponed and perhaps even avoided by some decisive stroke. To this configuration of circumstances must be added Hitler's implicit faith in his own military genius, a faith to all appearance unshaken by defeat and treason, a faith that accepted the possibility, even the probability, that the course of conflict might be reversed by a military stroke of genius. There was, after all, a prototype in German history which showed how the genius and the will of the Feldherr might wrest victory from certain defeat. Behind the desk in Hitler's study hung a portrait of Frederick the Great. This man, of all the great military leaders in world history, was Hitler's ideal. The axioms given by Frederick to his generals were on the tip of Hitler's tongue, ever ready to refute the pessimist or generalize away a sticky fact. When his generals protested the inability of soldier flesh and blood to meet further demands, Hitler simply referred to the harsh demands made of his grenadiers by Frederick. When the cruelties of the military punitive code were increased to the point that even the stomachs of Prussian officers rebelled, Hitler paraded the brutal code of Frederick's army before them. Even the oath taken by SS officer candidates was based on the Frederician oath to the flag. An omnivorous reader of military history, Hitler was fond of relating episodes therefrom as evidence of his catholic [9] military knowledge or as footnotes proving the soundness of a decision. In a very human way he selected those historical examples which seemed to support his own views. Napoleon, before the invasion of Russia, had forbidden any reference to the ill-fated campaign of Charles XII of Sweden because "the circumstances were altered." Hitler in turn had brushed aside the fate of both these predecessors, in planning his Russian campaign, because they had lacked tanks and planes. In 1944, however, Hitler's mind turned to his example, Frederick II, and found encouragement and support. Frederick, at the commencement of the Seven Years War, had faced superior forces converging on his kingdom from all points of the compass. At Rossbach and Leuthen he had taken great risk but had defeated armies twice the strength of his own. By defeating his enemies in detail, Frederick had been able to hang on until the great alliance formed against Prussia had split as the result of an unpredictable historical accident. Three things seemed crystal clear to Hitler as explanation for Frederick's final victory over his great enemies: victory on the battlefield, and not defeat, was the necessary preliminary to successful diplomatic negotiations and a peace settlement; the enemy coalition had failed to present a solid front when single members had suffered defeat; finally, Prussia had held on until, as Hitler paraphrased Frederick's own words, "one of [the] damned enemies gets too tired to fight any more." If Hitler needed moral support in his decision to prepare for the counteroffensive at a time when Germany still was reeling from enemy blows, it is very probable that he found this in the experience and ultimate triumph of Frederick called the Great. Although the first announcement of the projected counteroffensive in the Ardennes was made by Hitler in the meeting on 16 September, the idea had been forming for some weeks in the Fuehrer's mind. Many of the details in this development can never be known. The initial thought processes were buried with Hitler; his closest associates soon followed him to the grave, leaving only the barest information. The general outlines of the manner in which the plan took form can be discerned, however, of course with a gap here and there and a necessary slurring over exact dates.6 The first and very faint glimmerings of the idea that a counteroffensive must be launched in the west are found in a long tirade made by Hitler before Generaloberst Alfred Jodl and a few other officers on 31 July 1944. At this moment Hitler's eyes are fixed on the Western Front where the Allies, held fast for several weeks in the Normandy hedgerows, have finally broken through the containing German forces in the neighborhood of Avranches. Still physically shaken by the bomb blast which so nearly had cut short his career, the Fuehrer raves and rambles, boasts, threatens, and complains. As he meanders through the "conference," really a solo performance, one idea reappears [10] again and again: the final decision must come in the west and if necessary the other fronts must suffer so that a concentrated, major effort can be made there. No definite plans can be made as yet, says Hitler, but he himself will accept the responsibility for planning and for command; the latter he will exercise from a headquarters some place in the Black Forest or the Vosges. To guarantee secrecy, nobody will be allowed to inform the Commander in Chief West or his staff of these far-reaching plans; the WFSt, that is, Jodl, must form a small operational staff to aid the Fuehrer by furnishing any needed data.7 Hitler's arrogation to himself of all command and decision vis-à-vis some major and concerted effort in the west was no more than an embittered restatement, with the assassination attempt in mind, of a fact which had been stuffed down the throats of the General Staff and the famous field commanders since the first gross defeat in Russia and had been underlined in blood by the executions following the Putsch of 20 July. The decision to give priority to the Western Front, if one can take Hitler at his own word and waive a possible emotional reaction to the sudden Allied plunge through the German line at the base of the Cotentin peninsula, is something new and worthy of notice. The strategic and operational problem posed by a war in which Germany had to fight an enemy in the east while at the same time opposing an enemy in the west was at least as old as the unification of Germany. The problem of a war on two fronts had been analyzed and solutions had been proposed by the great German military thinkers, among these Moltke the Elder, Schlieffen, and Ludendorff, whose written works, so Hitler boasted, were more familiar to him than to those of his entourage who wore the red stripe of the General Staff. Moltke and Schlieffen, traveling by the theoretical route, had arrived at the conclusion that Germany lacked the strength to conduct successful offensive operations simultaneously in the east and west. Ludendorff (Hitler's quondam colleague in the comic opera Beer Hall Putsch) had seen this theory put to the test and proven in the 1914-1918 war. Hitler had been forced to learn the same lesson the hard way in the summer of 1944. A fanatical believer in the Clausewitzian doctrine of the offensive as the purest and only decisive form of war, Hitler only had to decide whether his projected counteroffensive should be made in the east or the west. In contrast to the situation that had existed in the German High Command of World War I, there was no sharp cleavage between "Easterners" and "Westerners" with the two groups struggling to gain control of the Army High Command and so dictate a favored strategy. It is true that OKH (personified at this moment by Guderian) had direct responsibility for the war on the Eastern Front and quite naturally believed that victory or defeat would be decided there. On the other hand, OKW, with its chiefs Keitel and Jodl close to the seat of power, saw the Western Front as the paramount theater of operations. Again, this was a natural result of the direct responsibility assigned this headquarters for the conduct [11] of all operations outside of the Eastern Front. Hitler, however, had long since ceased to be influenced by his generals save in very minor matters. Nor is there any indication that Keitel or Jodl exercised any influence in turning the Fuehrer's attention to the west. There is no simple or single explanation for Hitler's choice of the Western Front as the scene of the great German counterstroke. The problem was complex; so were Hitler's mental processes. Some part of his reasoning breaks through in his conferences, speeches, and orders, but much is left to be inferred. As early as 1939 Hitler had gone on record as to the absolute necessity of protecting the Ruhr industrial area, the heart of the entire war-making machine. In November 1943, on the heels of Eastern Front reverses and before the Western Allies had set foot in strength across the Channel, Hitler repeated his fears for the Ruhr, "... but now while the danger in the East remained it was outweighed by the threat from the West where enemy success would strike immediately at the heart of the German war economy ....8 Even after the disastrous impact of the 1944 Soviet summer offensive he clung to the belief that the Ruhr factories were more important to Germany than the loss of territory in the east. He seems to have felt that the war production in Silesia was far out of Soviet reach: in any case Silesia produced less than the Ruhr. Then too, in the summer and early autumn of 1944 the Allied air attacks against the Ruhr had failed to deliver any succession of knockout blows, nor was the very real vulnerability of this area yet apparent. Politically, if Hitler hoped to lead from strength and parlay a military victory into a diplomatic coup, the monolithic USSR was a less susceptible object than the coalition of powers in the west. Whereas Nazi propagandists breathed hatred of the Soviet, the tone toward England and the United States more often was that of contempt and derision, as befitted the "decadent democracies." Hitler seems to have partaken of this view, and in any case he believed that the Allies might easily split asunder if one of them was jolted hard enough. The inability of the western leaders to hold their people together in the face of defeat was an oft-expressed and cardinal axiom of the German Fuehrer, despite the example of the United Kingdom to the contrary. From one point of view the decision for the west was the result of progressive elimination as to the other fronts. In no way could victory in Italy or Finland change the course of the war. Russia likewise offered no hope for any decisive victory with the forces which Germany might expect to gather in 1944. The campaigns in the east had finally convinced Hitler, or so it would appear, that the vast distances in the east and the seemingly inexhaustible flow of Soviet divisions created a military problem whose solution lay beyond the capabilities of the Third Reich as long as the latter was involved in a multifront war. To put it another way, what Germany now needed was a quick victory capable of bearing immediate diplomatic fruit. Between 22 June 1941 and [12] 1 November 1942 the German armies in the USSR had swept up 5,150,000 prisoners of war (setting aside the Russians killed or severely wounded) but still had failed to bore in deep enough to deliver a paralyzing blow. A quick and decisive success in the second half of 1944 against 555 Soviet units of division size was out of the question, even though Hitler would rave about the "Russian bluff" and deride the estimates prepared by his Intelligence, Fremde Heere 0st. Still other factors were involved in Hitler's decision. For one thing the Allied breakout in Normandy was a more pressing danger to the Third Reich than the Soviet advance in the east. Intuitively, perhaps, Hitler followed Schlieffen in viewing an enemy on the Rhine as more dangerous than an enemy in East Prussia. If this was Hitler's view, then the Allied dash across France in the weeks following would give all the verification required. Whether at this particular time Hitler saw the German West Wall as the best available springboard for a counteroffensive is uncertain. But it is quite clear that the possession of a seemingly solid base for such an operation figured largely in the ensuing development of a Western Front attack. After the announcement of the west as the crucial front, in the 31 July conference, Hitler seemingly turned his attention, plus such reserves as were available, to the east. Perhaps this was only a passing aberration, perhaps Hitler had been moved by choler in July and now was in the grip of indecision. Events on both fronts, however, were moving so rapidly that a final decision would have to be made. The death of Generalfeldmarschall Guenther von Kluge, Commander in Chief West, seems to have triggered the next step toward irrevocable commitment. Coincident with the appointment of Model to replace the suicide, Hitler met with a few of his immediate staff on 19 August to consider the situation in France. During this conference he instructed Walter Buhle, chief of the Army Staff at OKW, and Speer, the minister in charge of military production and distribution, to prepare large allotments of men and materiel for shipment to the Western Front. At the same time Hitler informed the conferees that he proposed to take the initiative at the beginning of November when the Allied air forces would be unable to fly. By 19 August, it would appear, Hitler had made up his mind: an attack would be made, it would be made on the Western Front, and the target date would be early November. The remaining days of August were a nightmare for the German divisions in the west and for the German field commanders. Shattered into bits and pieces by the weight of Allied guns and armor, hunted and hounded along the roads by the unopposed Allied air forces, captured and killed in droves, the German forces in France were thoroughly beaten. All requests for permission to withdraw to more defensible positions were rejected in peremptory fashion by Hitler's headquarters, with the cold rejoinder "stand and hold" or "fight to the last man." In most cases these orders were read on the run by the retreating divisions. At the beginning of September Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model was "put in the big picture" by the Fuehrer. Hitler gave as his "intention" for the [13] future conduct of operations that the retreating German armies must hold forward of the West Wall, thus allowing time needed to repair these defenses. In general the holding position indicated by Hitler ran from the Dutch coast, through northern Belgium, along the forward edge of the West Wall in the sector between Aachen and the Moselle River, then via the western borders of Alsace and Lorraine to some indefinite connection with the Swiss frontier. Here, for the first time on the Western Front, Hitler relaxed his seemingly pigheaded views on the unyielding defense and permitted, even enjoined, a withdrawal. This permission, however, was given for a very definite purpose: to permit the reorganization of Germany's defense at or forward of the West Wall, the outer limit of Greater Germany. Despite the debacle in France, Hitler professed himself as unworried and even sanguine. On the first day of September, Rundstedt was recalled to the position of Commander in Chief West which he had been forced to relinquish at the end of June under Hitler's snide solicitude for his "health." The new commander was told that the enemy in the west would shortly be brought to a halt by logistic failures (in this forecast the Fuehrer's intuition served him well) and that the giant steps being taken toward Germany were the work of isolated "armored spearheads" which had outrun the main Allied forces and now could be snipped off by local counterattacks, whereupon the front would stabilize. Since the U. S. Third Army under Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., was advancing with its right flank open (contact with the U.S. Seventh Army driving north from the Mediterranean had not as yet been made), Hitler ordered Rundstedt to counterattack against this exposed flank and cut the advanced American armor by seizing Reims. For this unenviable task the Fifth Panzer Army, at the moment little more than an army headquarters and a few army troops, would be beefed up and handed over to the new commander in chief.9 The thrust to Reims was not intended as the grand-scale effort to regain the initiative which by this time was fully rooted in Hitler's mind. The Fifth Panzer Army was to counterattack, that is, to be committed with limited forces for the attainment of a limited object. The scheme visualized for November, no matter how vague its shape in the first week of September, was that of a counteroffensive, or a major commitment of men and matériel designed to wrest the initiative from the enemy in pursuance of a major strategic victory. The counterattack was made, but not as planned and not toward Reims. The base for the proposed operation, west of the Moselle River, was lost to the Americans before the attack could be launched. A watered-down variant on the east side of the Moselle was set in motion on 18 September, with Luneville as the first objective; it degenerated into a series of small, piecemeal attacks of only momentary significance.10 This, the single major effort to win time and space by counterattack and so give breathing space to the Reich and footing for a counteroffensive, must be written [14] a complete failure. Nonetheless, by the second week of September there were encouraging evidences all along the Western Front that the battered German troops were beginning to get a toehold here and there, and that the enemy who had run so fast and so far was not holding the pace. Except for a handful of bunkers and pillboxes the battle front was in process of stabilizing forward of the West Wall. Meanwhile German efforts to reactivate and rearm these fortifications were in full swing. Despite the somber and often despairing reports prepared by Model and his successor, Rundstedt, during late August and early September, Hitler and his intimate staff in the East Prussian headquarters continued to give thought to a decisive attack in the west. About 6 September, Jodl gave the Fuehrer an evaluation of the situation inherited by Rundstedt. The task at hand was to withdraw as many troops from the line a possible, refit and re-form units. On the scale required, this work could not be completed before the first day of November. Since he was probably listening to a clearer phrasing of his own cloudy concept, Hitler agreed, but with the proviso that the battle front must be kept as far to the west as possible. The reason, expressed apparently for the first time, was that the Allied air effort had to be kept at a distance from the Rhine bridges or the consequences might be disastrous. Did Hitler fear that fighter-bombers operating from fields in France or Belgium might leave the Rhine crossing complex stricken and incapable of supporting the line of communications to the armies then on the left bank of the Rhine? Or did he foresee that the Rhine bridges would be systematically hammered in an effort to strangle the German bid for the initiative when the day for the counteroffensive came? As a target date, 1 November now seemed firm. Hitler had tossed it out in an off-the-cuff gesture; Jodl had evaluated it in terms of the military situation as seen in the remote Wolf's Lair; and in his first report after assuming command, Rundstedt unwittingly added his blessing by estimating that the West Wall defenses would be refurbished and manned sometime around 20 October. The Commander in Chief West, be it noted, was not yet privy to any attack plans except those for the Fifth Panzer Army. Since Hitler was convinced that his western armies would hold before or at the West Wall position, and by intuition or self-hypnosis he held to this conviction, the next step was to amass the forces needed to issue offensively from the West Wall base of operations. During July and August eighteen new divisions had been organized, fifteen of which were sent to the Eastern Front, one to Norway, and only two to the Western Front. A further Hitler order on 2 September commanded the creation of an "operational reserve" numbering twenty-five new divisions. This order lay behind the comb-out program entrusted to Goebbels and definitely was in preparation for a western counteroffensive. Early in August the Western Front had been given priority on tanks coming off the assembly line; this now was made a permanent proviso and extended to cover all new artillery and assault gun production. Further additions to the contemplated reserve would have to come from other [15] GENERAL JODL theaters of war. On 4 September OKW ordered a general movement of artillery units in the Balkans back to the Western Front. The southeastern theater now was bereft of much of its early significance and the German forces therein stood to lose most of their heavy equipment in the event of a Soviet drive into the Balkans. The northern theater likewise was a potential source of reinforcements, particularly following the defection of Finland in early September and the collapse of a homogeneous front. These "side shows" could be levied upon for the western counteroffensive, and even the sore-beset German armies in the east, or so Hitler reasoned, could contribute armored divisions to the west. But in the main, the plan still evolving within the closed confines of the Wolf's Lair turned on the withdrawal and rehabilitation of units which had taken part in the battle for France. As a first step the SS panzer divisions in the west were ordered out of the line (13 September) and turned over to a new army headquarters, that of the Sixth Panzer Army. Having nominated a headquarters to control the reconstitution of units specifically named for participation in an attack to be made in the west, the logical next step in development of the plan came in Hitler's announcement on 16 September: the attack would be delivered in the Ardennes and Antwerp would be the objective. Why the Ardennes? To answer this question in a simple and direct manner is merely to say that the Ardennes would be the scene of a great winter battle because the Fuehrer had placed his finger on a map and made a pronouncement. This simplified version was agreed to in the months after the war by all of those major German military figures in Hitler's entourage who survived the last battles and the final Gotterdammerung purges. It is possible, however, that Hitler had discussed the operational concept of a counteroffensive through the Ardennes with Jodl-and before the 16 September edict. The relationship between these two men has bearing on the entire "prehistory" of the Ardennes campaign. It is analyzed by the headquarters diary-keeper and historian, Maj. Percy E. Schramm, as follows:

[16]

The evidence is clear that Jodl and a few of his juniors from the Wehrmacht Operations Staff did examine the Ardennes concept very closely in the period from 25 September, when Hitler gave the first order to start detailed planning, to 11 October, when Jodl submitted the initial operations plan. Other but less certain evidence indicates that those present in the select conference on 16 September were taken by surprise when Hitler made his announcement. Jodl definitely ascribes the selection of the Ardennes to Hitler and Hitler alone, but at the time Jodl expressed this view he was about to be tried before an international tribunal on the charge of preparing aggressive war. Even so, the "argument from silence,"-the fact that there is no evidence of other thought on the Ardennes as the point of concentration prior to Hitler's statement on 16 September-has some validity. The most impressive argument for ascribing sole authorship of the Ardennes idea to Hitler is found in the simple fact that every major military decision in the German High Command for months past had been made by the Fuehrer, and that these Hitler decisions were made in detail, never in principle alone. The major reasons for Hitler's selection of the Ardennes were stated by himself, although never in a single tabulation on a single occasion nor with any ordering of importance:

[17] Although Hitler never referred directly to the lightning thrust made in 1940 through the Ardennes as being in any sense a prototype for the operation in the same area four and a half years later, there is indication of a more than casual connection between the two campaigns in Hitler's own thinking. For example, during the 16 September expose he set the attainment of "another Dunkirk" as his goal. Then, as detailed planning began, Hitler turned again and again to make operational proposals which had more than chance similarity to those he had made before the 1940 offensive. When, in September 1939, Hitler had announced his intention to attack in the west, the top-ranking officers of the German armed forces had to a man shown their disfavor for this daring concept. Despite this opposition Hitler had gone ahead and personally selected the general area for the initial penetration, although perhaps with considerable stimulation from Generalfeldmarschall Fritz Erich von Manstein. The lightning campaign through the Netherlands, Belgium, and France had been the first great victory won by Hitler's intuition and the Fuehrerprinzip over the German General Staff, establishing a trend which had led almost inevitably to the virtual dictatorship in military command exercised by the Fuehrer in 1944. Also, the contempt for Allied generalship which Hitler continually expressed can be regarded as more than bombast. He would be prone to believe that the Western Allies had learned nothing from the experience of 1940, that the conservative military tradition which had deemed the Ardennes as impossible for armor was still in the saddle, and that what German arms had accomplished in 1940 might be their portion a second time. Two of the factors which had entered into the plans for the 1940 offensive still obtained: a very thin enemy line and the need for protecting the Ruhr. The German attack could no longer be supported by an air force which outweighed the opposition, but this would be true wherever the attack was delivered. Weather had favored movement through the Ardennes defiles in the spring of 1940. This could hardly be expected in the month of November, but there is no indication that Hitler gave any thought to the relation of weather and terrain as this might affect ground operations in the Ardennes. He tended to look at the sky rather than the ground, as the Luftwaffe deteriorated, and bad weather-bad flying weather-was his desire. In sum, Hitler's selection of the Ardennes may have been motivated in large part by the hope that the clock could be turned back to the glorious days of 1940.12 [18]

|