While the Continental Army in the north took shape in 1776, the colonies to the south also turned to military preparations. The process began, much as it had in New England, with the formation of forces by revolutionary governments to oppose British threats in the immediate vicinity of each colony. Congress brought these forces into the Continental establishment and raised others not in accord with a general plan but in response to circumstances, although it did attempt to introduce some order by establishing separate Middle and Southern Departments for administration and command and for expansion of the staff. By the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Continental regiments represented every state. When the British then mounted a massive invasion against New York, Washington moved most of his Main Army from Boston and augmented it, under congressional direction, with new Continental units and short-term militia. As units from the south arrived to meet this crisis, the Continental Army began to take on the character of a genuine national force.

Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia began 1775 without significant British garrisons. They were under British governors, however, and regular troops were nearby in Florida. Like their northern neighbors, the southern colonies soon replaced their Royal governments with new political bodies. The new governments raised troops as soon as the deposed governors posed a military or naval threat. Because these early colonial efforts were undertaken with minimal supervision by the Continental Congress, a diversity of regimental organizations emerged. That diversity was wider in the south than it had been in New England and New York because the southern colonies were less homogeneous and had accumulated more varied experiences in the colonial wars. During 1776 Congress moved to provide the type of unified central control that it had already established in the north.

The aggressiveness of Governor John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, led Virginia to act first. When it organized an extra-legal assembly in March 1775, the more radical element led by Patrick Henry was unable to persuade the colony to raise regular troops. The news of Lexington and Concord, however, had produced a change in attitude when the Virginia Convention reconvened in July. Although there was general agreement on the need to take military action, debates over actual measures lasted until 21 August. Proposals for an armed force of 4,000 men were scaled down to three 1,000-man regiments, but they still could not gain approval. The final com-

promise divided the colony into sixteen regional districts: fifteen on the mainland and another on the peninsula between the Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay. Each district established a committee of safety to raise one company of regular, full-time troops for one year's service and to form a ten-company battalion of minutemen within the militia system to provide a better trained local defense force. The minutemen replaced volunteer companies formed in 1774 and 1775. The Eastern Shore district did not form a regular company, but it received authorization for a somewhat larger minuteman regiment. The convention also created a Committee of Safety and adopted Articles of War and the current British drill manual.1

After reporting to Williamsburg, the fifteen regular companies (about 1,020 men) were organized on 21 October into two regiments. The 1st Virginia Regiment under Patrick Henry contained 2 rifle companies and 6 musket companies; the 2d Virginia Regiment under William Woodford also had 2 rifle companies but only 5 musket companies. The rifle companies—intended as light infantry—came from the frontier districts; the musketmen, from more settled regions. Each had a captain, 2 lieutenants, an ensign, 3 sergeants, a drummer, a fifer, and 68 rank and file. The district committees selected the company officers, while the convention appointed three field officers for each regiment. Regimental staffs contained a chaplain, an adjutant, a paymaster who doubled as mustermaster, a quartermaster, a surgeon with two mates, and a sergeant major. Because Henry was the senior officer, the 1st also had a secretary. The officers of Virginia's two regiments carried impressive credentials: all were political leaders, and four had significant combat experience. The captains were prominent in local affairs, although most were too young to have served in the French and Indian War.

The compromise which created the two regiments also included five independent companies to garrison strategic frontier posts. They were under the overall command of Capt. John Neville, who established his headquarters at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh). Four were rather large: a captain, 3 lieutenants, an ensign, 4 sergeants, 2 drummers, 2 fifers, and 100 rank and file; the fifth had only a single lieutenant and 25 enlisted men. Two of the large companies manned Fort Pitt while the small one garrisoned Fort Fincastle at the mouth of the Wheeling River. These three companies were recruited in the West Augusta District, a partially organized region on the northwest frontier. Another company, from Botetourt County, defended Point Pleasant, and the last defended its home county of Fincastle. The use of independent companies followed the British Army's practice of sending separate units to remote colonial garrisons.2

Skirmishes with Lord Dunmore's forces in the Hampton Roads area during the late fall culminated in a minor battle at Great Bridge. The Virginia Convention reacted by passing legislation on 11 January to raise 72 more companies of regulars. It

1. William J. Van Screevan et al., eds., Revolutionary Virginia:

The Road to Independence (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia,

1973- ), 3:319-43, 392-409, 427-29, 450-59, 471-72; 497-504. William Waller

Henning, comp., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws

of Virginia, 14 vols. (1821; reprint ed., Charlottesville: Jamestown Foundation,

1969), 9:9-50; George Mason, The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792, ed.

Robert A. Rutland, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1970), 1:245-57; The Virginia Gazette (ed. Alexander Purdie),

25 Aug 75; Brent Tarter, ed., "The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment,

September 27, 1775-April 15, 1776," Virginia Magazine of History and

Biography 85 (1977):170-71.

2. Van Screevan, Revolutionary Virginia, 3:343, 404; Reuben

Gold Thwaites and Louis Phelps Kellogg, eds., The Revolution on the Upper

Ohio, 1775-1777 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1908), pp. 12-17.

| Field | Staff | Each Company | Aggregate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony | Col-onel | Lieut-enant Col-onel | Major | Ad-jutant | Quarter-master | Sur-geon | Sur-geon’s Mate | Chap-lain | Ser-geant Major | Quarter-master Sergeant | Fife and Drum Major | Pay-master | Num-ber of Comp- anies | Cap-tain | Lieut-enant | Ensign | Ser-geant | Cor-poral | Drum-mer | Fifer | Pri-vates | Of-ficers | Staff Of-ficers | Noncom-misioned Officers |

Drum-mers and Fifers | Pri-vates | Total Strength |

| Continental | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 76 | 35 | 6 | 68 | 16 | 608 | 733 |

| Virginia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 a | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 64 | 43 | 6 | 83 | 20 | 640 | 792 |

| South Carolina Rifle | lb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7b | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 92 | 31 | 4 | 58 | 0 | 644 | 737 |

| Southern Ranger | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 32 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 500 | 554 |

| Pennsylvania State Musket | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 52c | 27 | 5 | 32 | 16 | 420 | 500 |

| Pennsylvania State Rifled | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 68 | 53 | 8 | 96 | 24 | 819 | 1,000 |

| Rhode Island State | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 50 | 39 | 4 | 96 | 24 | 600 | 763 |

| Maryland | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | le | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 2f | if | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 60f | 40 | 4 | 73 | 18 | 544 | 679 |

| Maryland Separate Cos | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 92 | 28 | 0 | 56 | 14 | 736 | 806 |

a In most regiments seven musket and three rifle companies.

b The 6th South Carolina Regiment had no colonel and only five companies.

c Some companies authorized one additional private.

d Two battalions.

e Clerk.

f Light infantry company had three lieutenants, no ensign, and four more privates.

expanded the 1st and 2d Virginia Regiments to ten companies each, added a sergeant to each company, and somewhat increased the regimental staff. (Table 3) The convention also established six new regiments of the same size, each with seven musket and three rifle companies, plus a ninth regiment with only seven companies to replace the minutemen on the Eastern Shore. Protection of the western coast of the Chesapeake Bay was provided by pairs of regiments assigned to sectors separated by the James, York, and Rappahannock Rivers. The 8th Virginia Regiment was unique in that the convention intended to raise it from the German-Americans of the Shenandoah Valley and, therefore, exempted it from having a fixed ratio of riflemen to musketmen. The Committee of Safety assembled the other new regiments on a regional basis, although it continued to draw the rifle companies from frontier counties. The new companies were raised by individual counties, and the men were enlisted to serve until 10 April 1778. The new field officers, like the earlier set, were an experienced group: six of the seven colonels had served with Washington in the French and Indian War. Company officers and many of the enlisted men came from the minutemen battalions.3

The nine regiments, like the frontier companies, were raised as state troops for the defense of Virginia and its neighbors. That fact, the ten-company organization, and the short enlistments made the regiments similar to the earlier Provincials. The financial burden of such a large force, however, soon led the colony to ask that the regiments be transferred to the Continental Army. On 28 December 1775, Congress, which was already moving to broaden the geographical base of the Continental Army, authorized six Virginia regiments. The Virginia delegates engaged in prolonged negotiations before Congress accepted all nine regiments. The 1st and 2d retained seniority by being adopted retroactively; the others came under Continental pay when they were certified as full. Virginia did not alter its regimental organization to conform to Continental standards, and the transfer did not alter the terms of enlistment. It did require the officers to exchange their colony commissions for Continental ones, and a few refused and resigned. When Virginia requested Congress to appoint general officers to command these troops, Washington objected to Henry's lack of military background and successfully blocked his appointment. In the end, two men who had served under Washington were appointed brigadier generals: Andrew Lewis on 1 March 1776 and Hugh Mercer on 5 June.4

The Virginia Convention had authorized an artillery company on 1 December 1775 consisting of a captain, 3 lieutenants, a sergeant, 4 bombardiers, 8 gunners, and 48 matrosses. On 13 February the Committee of Safety selected James Innis as captain and Charles Harrison, Edward Carrington, and Samuel Denney as lieutenants. Congress adopted the company on 19 March, and soon after instructed Dohicky Arundel, a French volunteer, to raise another artillery company in Virginia. When Innis transferred to the infantry, Arundel attempted to merge the two companies, but

3. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:75-92; Force,

American Archives, 4th ser., 4:78-83, 118; Van Screevan, Revolutionary

Virginia, 4:467-69, 497-99; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of

Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (Richmond: Virginia

State Library, 1875-93), 8:75-149. The 9th expanded to ten companies on

18 May: Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1528, 1556; Henning,

Statutes at Large, 9:135-38.

4. JCC, 3:463; 4:132, 181, 235; 5:420, 466, 649;

Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:116-17; 5th ser., 1:719-22;

Fitzpatrick, Writings, 4:379-84; Jefferson, Papers, 1:482-84;

Van Screevan, Revolutionary Virginia, 4:421-22, 470-71; Smith, Letters

of Delegates, 3:100-102, 123-24, 240, 245-46, 248-49, 252, 316n, 440;

Burnett, Letters, 2:31-32.

he was killed on 12 July while experimenting with a mortar. The companies retained separate identities although they worked closely with each other.5

In May 1776 the colony reorganized the frontier defense companies, for the most part retaining their large size. Reenlistments at Fort Pitt and Point Pleasant filled one company from each place. A third was organized in Botetourt County for duty at Point Pleasant. New, smaller companies (3 officers, 3 sergeants, a drummer, a fifer, and 50 rank and file) were raised in Hampshire and Augusta Counties to garrison Wheeling (Fort Fincastle) and a post on the Little Kanawha River. All were under Neville, who was promoted to major. The same legislation ordered reenlistment of the men of the 1st and 2d Virginia Regiments for three years.6 Virginia's regular forces were more than a match for Lord Dunmore, and the British soon withdrew to New York.

North Carolina's revolutionary leadership was less sure than Virginia's of its popular support and consequently turned to outside assistance sooner. The colony contained many recent Scottish immigrants who were still loyal to the Crown, and old grievances left the backcountry's willingness to follow Tidewater planters in doubt. On 26 June 1775 the North Carolina delegates secured a congressional promise to fund a force of 1,000 men. This support enabled the colony's leaders to act.7

Aside from raising the Continental force, North Carolina organized six regional military districts and instructed each to raise a ten-company battalion of minutemen. At the same time, the colony disbanded its volunteer companies to remove any obstacles to recruiting. The minutemen had the same organization as the colony's Continental companies: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, and 50 rank and file. This structure was quite similar to that of the Virginia minutemen. On 1 September the colony's 1,000 continentals were arranged in 2 regiments, each consisting of 3 field officers, an adjutant, and 10 companies. The companies assembled at Salisbury beginning in October. The colony's total response was a compromise. Eastern interests received the two regular regiments to defend the coastline from naval vessels supporting former Governor Josiah Martin. Less threatened areas relied on the less expensive minutemen.8

On 28 November 1775 the Continental Congress ordered both North Carolina regiments reorganized on the new Continental eight-company structure. It went on to authorize a third regiment on 16 January 1776 and two more on 26 March. Colonial concurrence was required to raise the new regiments. However, the Provincial Congress was receptive and on 9 April approved raising the three new regiments for two and a half years. The Continental Congress had already rewarded North Carolina's prompt actions in 1775 by promoting Cols. James Moore and Robert Howe to brigadier general on 1 March 1776. The Provincial Congress had second thoughts, however, and on 13 April it ordered that its regular forces be reorganized as six instead of five regiments. Five new companies were raised by each of the six military districts, and

5. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:75-92; JCC,

4:212, 364. Virginia Gazette (Purdie), 16 Feb and 12 Jul 76;

Charles Campbell, ed., The Orderly Book of That Portion of the American

Army Stationed at or Near Williamsburg, Va., Under the Command of General

Andrew Lewis From March 18th, 1776, to August 28th, 1776. (Richmond:

privately printed, 1860), pp. 26-27, 36-37; Lee, Papers, 1:367-68,

416-17, 440-43, 477-80; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:102n, 108-9,

168-69, 397, 469-70, 570-72.

6. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:135-38; Force,

American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1532, 1556, 1568; Henry Read McIlwaine

et al., eds., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia, 4

vols. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1931-67), 1:97, 108, 148, 173.

7. JCC, 2:107; 3:330; Smith, Letters of Delegates,

1:545.

8. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:255-70;

3:181-210, 679, 1087-94.

the remaining two were organized in the colony at large. The staff of these units deviated from the Continental model by omitting the fife major and adding a commissary of stores, an armorer, and a wagonmaster. The Continental Congress accepted the 6th North Carolina Regiment on 7 May (retroactively) and subsequently adopted three troops of light horse and an artillery company which the colony had raised during the summer.9

Meanwhile, continued concern for the security of the coast had led to a proposal to add another regular regiment, with six companies. General Moore persuaded the Provincial Congress to modify this plan on 29 April. Instead of a seventh regiment, five independent companies of state troops were authorized to defend specific points. Two were standard-sized companies, but the other three each had only sixty privates. On 3 May a 24-man company was added to garrison a frontier fort.10

South Carolina's situation in 1775 was somewhat similar to North Carolina's. Again there was lingering tension between the Tidewater and backcountry, but the colony's leaders were more secure. Like Virginia, the colony decided to supplement the militia with regular state troops rather than turn immediately to the Continental Congress. The Provincial Congress adopted a regional compromise on 4 June. Two 750-man regiments of infantry were authorized to defend the Tidewater from possible attack by regular British troops. The "upcountry" received a third regiment of 450 mounted rangers to counter potential Indian raids. Since there was no immediate danger, the Provincial Congress limited expenses by restricting the companies to cadre strength when it issued recruiting orders on 21 June. The infantry regiments were authorized ten 50-men companies each, a structure similar to that selected by North Carolina and Virginia in 1775. The nine ranger companies were allowed thirty men each. Competition for commissions was intense, and a minor mutiny occurred in some companies of the ranger regiment when the spirit of the regional compromise was violated by the assignment of a Tidewater militia officer as the regimental commander.11

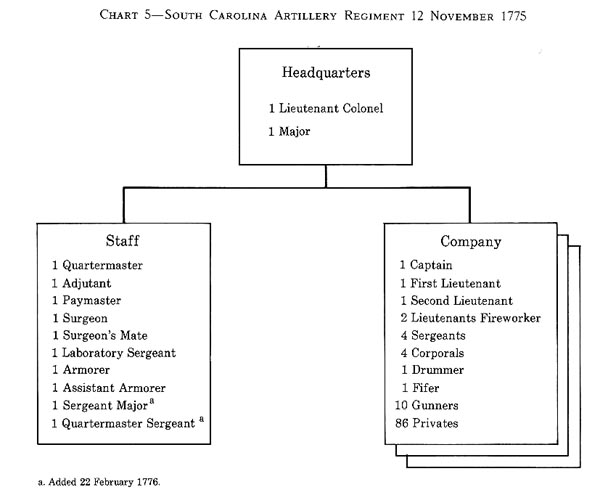

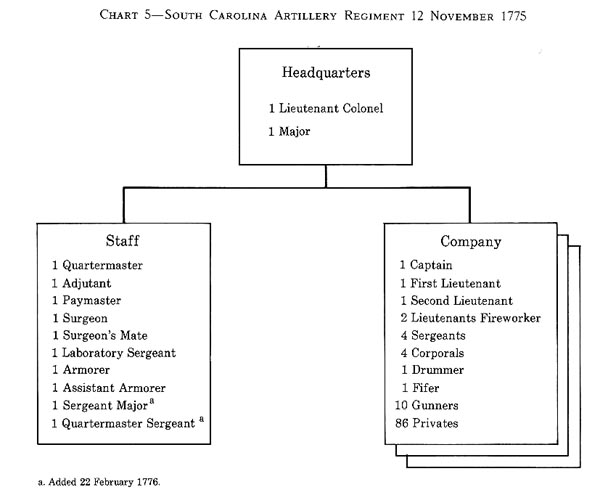

During the winter the South Carolina Provincial Congress expanded its forces. An artillery regiment, small but highly specialized, was established to man the fortifications at Charleston. (Chart 5) The 4th South Carolina Regiment drew its cadre from Charleston's elite militia artillerymen. A separate artillery contrary authorized at this time to defend Fort Lyttleton at Port Royal was not raised. On 22 February 1776 the three original regiments were finally allowed to recruit to full strength, and shortly thereafter two rifle regiments were added. (See Table 3.) The 5th South Carolina Regiment had seven companies, recruited in the Tidewater. The 6th had only five companies; Thomas Sumter raised this regiment along the northwestern frontier where many of the inhabitants were former Virginians. Each rifle company contained four

9. JCC, 3:387-88; 4:59, 181, 237, 331-33; 5:623-24;

8:567; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:18-19, 42-44, 100-103, 123-24,

315-18, 448; Burnett, Letters, 1:448; Force, American Archives,

4th ser., 4:299-308; 5:68, 859-60. 1315-68; 6:1443-58.

10. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 5:1330-31,

1341-42, 1348.

11. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:897,

953-54; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution. So Far

As It Related to the States of North and South Carolina and Georgia, 2

vols. (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 1:64-65; John Drayton, Memoirs

of the American Revolution. From Its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive,

2 vols. (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1821), 1:249, 255, 265, 286-88,

323, 352-53; R. W. Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American

Revolution, 3 vols. (Columbia and New York: Banner Steam-Power Press

and D. Appleton & Co., 1853-57), vol. A, pp. 104-5.

officers and one hundred men. At the same time, artillery companies were allocated for Fort Lyttleton (100 men) and Georgetown (60).12

On 4 November 1775 the Continental Congress had directed South Carolina to raise three Continental regiments with the standard Continental infantry organization. A second act, on 25 March 1776, increased the quota to five regiments. The colony did not immediately transfer its units to the Continental Army but tried simply to delegate operational control over them. Congress did not accept that alternative. On 18 June it decreed that all of the regiments except the rangers had been adopted by the earlier acts. As a major concession, however, it promised not to send more than one-third of the troops outside South Carolina without prior notice. The rangers and a similar Georgia mounted unit were adopted on 24 July with a special organization and a requirement that they seine on foot as well as on horseback. (See Table 3.) Congress restored seniority by other legislation.13

12. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:27-76;

5:561-615; Moultrie, Memoirs, 1:93, 126-27; Gibbes, Documentary

History, vol. A, pp. 246-48.

13. JCC, 3:325-27; 4:235; 5:461-62, 606-7, 760;

Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:440; Moultrie, Memoirs, 1:141;

Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 1:631-32; Lee, Papers, 2:10-12,

37-39, 57, 173, 199-202, 251, 254, Thomas Pinckney, "Letters of Thomas

Pinckney, 1775-1780," ed. Jack L. Cross, South Carolina Historical Magazine

58 (1957):29-30.

THOMAS SUMTER (1734-1832), "the Gamecock," organized the 6th South Carolina Regiment and commanded it until he retired in 1778. Later in the war he became one of the most effective southern leaders of irregulars. The famous fort in Charleston harbor is named for him. (Portrait by Rembrandt Peale.)

Georgia, like North Carolina, waited for congressional support before risking military action. It had only 3,000 males of military age and was the most exposed colony. When Congress authorized South Carolina's three regiments on 4 November 1775, it also directed Georgia to raise a standard infantry regiment. Because communications with the colony took so long, its Provincial Congress was allowed to appoint all officers, not just those of company-grade. After factions within the Provincial Congress fought for control of the regiment, a compromise gave command to Lachlan McIntosh, the leader of the Scottish element in the colony. Two representatives of the Savannah mercantile interests were named as the other field officers. Most of the company positions went to sons of the planters who constituted the "Country Party." The Provincial Congress and the state government that succeeded it caused continual troubles for senior Continental officers by asserting a right to retain an interest in the regiment's affairs.14

McIntosh began raising the regiment in February 1776, arming one of the companies with rifles. He correctly anticipated that limited resources would hamper his efforts: two months later the regiment had reached only half strength. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee supported the colony's efforts to have Congress raise six additional regiments elsewhere and to station them in Georgia. Before this recommendation arrived, Congress voted to have Georgia raise two additional regiments (one of which was to be composed of riflemen) and two artillery companies to garrison Savannah and Sunbury. On 24 July Congress adopted the colony's horse troops and expanded them into a regiment as well.15

14. JCC, 3:325-27; Allen D. Candler, ed., The

Revolutionary Records of the State of Georgia, 3 vols. (Atlanta: Franklin-Turner

Co., 1908), 1:77-78, 273; Lee, Papers, 2:216-29, 254; Force, American

Archives, 4th ser., 2:1553; 6:1159-60; Lachlan McIntosh, "The Papers

of Lachlan McIntosh, 1774-1799," ed. Lilla M. Hawes, Georgia Historical

Quarterly 39 (1955):53.

15. JCC, 5:521, 606-7; Lee, Papers, 2:48-49, 107-17,

241-45, 249; Candler, Revolutionary Records, 1:124, 194-99; Force,

American Archives, 4th ser., 4:1159-61; 5:1106-9.

McIntosh made little progress in organizing the new units despite receiving permission from Virginia and North Carolina to recruit within their borders. Low bounties, year-long enlistments, and a fear in colonies to the north that Georgia's climate was fatal discouraged enlistments. Although the ranger regiment under his brother William did better than the infantry regiments and was on duty by late October, the colony was fortunate that British pressure was minimal.16

In many respects the first year of military preparations in the south resembled New England's efforts in 1775. Each colony raised a separate force independently or with congressional encouragment. Regimental structures varied, although a 10-company, 500-man formation had some regional appeal. These forces gradually were adopted as part of the Continental Army. Two key differences set the south apart. The region, with little manpower to spare from a plantation economy, turned rapidly to enlisting men for long terms, typically two years. Many of the colonies also resisted surrendering full control over their troops to the national government in distant Philadelphia. All refused to comply completely with the standard eight-company structure for Continental infantry regiments.

The 1776 military effort in the south culminated on 28 June with the repulse of a British attack on Charleston, South Carolina. A return for the forces in that state shortly after the event shows that all six South Carolina regiments were there along with the 8th Virginia Regiment; the 1st, 2d, and 3d North Carolina Regiments; and a troop of North Carolina horse. Excluding the artillery and cavalry, the concentration of continentals at Charleston included 239 officers, 30 staff officers, 209 sergeants, 86 drummers and fifers, and 3,158 rank and file. About 500 were sick, and almost another hundred were absent on furlough. The force was thus well below authorized levels. The three North Carolina regiments were about half full; the 8th Virginia Regiment about three-quarters full. The three senior South Carolina regiments averaged about 350 men apiece, but the newer 5th and 6th Regiments were both still under 300.17

In addition to the concentration at Charleston, by July sizable Continental forces were on hand in all the southern states. Georgia had one infantry regiment nearing full strength and a partially organized mounted regiment. Two other infantry regiments and two artillery companies were beginning to recruit. North Carolina was held by three regiments, two troops of horse, and an artillery company. In Virginia, where Governor Dunmore was preparing to depart, eight infantry regiments defended the Tidewater area while five companies were on the frontier.

Even before the decisive victory at Charleston, Virginia had bested Governor Dunmore; North Carolina had crushed a Loyalist uprising at Moore's Creek Bridge; and Georgia had chased off the forces of its former governor. Joint operations had silenced Cherokees in the interior. The fact that militia or minutemen had played a major role in defeating the Loyalists and Indians, however, led to difficulty in recruiting for the Continental regiments since their success had reinforced colonial leaders' belief that militia forces were adequate for local defense. These southern leaders consequently did not give the Continental units the same support that their northern counterparts did. When General Lee left the south in the autumn of 1776, he feared that "it is not

16. Ibid., 5th ser., 1:6-8; McIntosh, "Papers," 38 (1954):161-66,

253-57; Candler, Revolutionary Records, 1:213; "Letters Colonial

and Revolutionary," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 42

(1918):77-78.

17. Monthly Return, Forces in South Carolina, July 1776,

Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 1:631-32.

LACHLAN MCINTOSH (1725-1806) was Georgia's ranking Continental officer. He raised the 1st Georgia Regiment and later commanded the Western Department as a brigadier general. He is best known, however, as the man who killed Button Gwinnett—one of Georgia's signers of the Declaration of Independence—in a duel. (Postwar portrait by Charles Willson Peale.)

impossible that the late repulse of the Enemy may be fatal to us [for] we seem now all sunk into a most secure and comfortable sleep."18

New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland also participated in Congress' expansion of the military effort in 1776. Like the south, these middle colonies were more diverse in their origins and ethnic composition than New England. On the other hand, the area was much closer to the national authority in Philadelphia. Proximity simplified communications and enabled the governments of these colonies to coordinate their efforts with Congress and to avoid the variety of unit structures of the other colonies. By waiting to raise troops until they had instructions from Congress, they also reduced their expenses.

Aside from the original 1775 riflemen, the first troops that Congress requested from the middle colonies were two regiments from New Jersey. Anticipating that the British would attack New York City, Congress on 9 October 1775 asked that colony's Provincial Congress to replace the New York regiments that had marched to Canada. New Jersey asserted that it should name all the officers because, knowing its own citizens, it was in the best position to select the most effective men. Delegates in Congress who were committed more to local interests than national ones supported the colony, but the resulting debate was won by other delegates who hoped to strengthen Congress' role as a national government. In practice Congress would follow a compromise by commissioning individuals from those nominated by the governments of the respective colonies.19

18. Lee, Papers, 2:105-6.

19. JCC, 3:285-89, 305, 335, 429; Smith, Letters

of Delegates, 2:147-48, 155-56, 171, 253, 489-90; Force, American

Archives, 4th ser., 3:1050-51, 1224-25, 1240; William Livingston to

Lord Stirling, 8 Nov 75, William Alexander Papers, New-York Historical

Society (hereafter cited as Stirling Papers); Rossie, Politics of Command,

pp. 26-30, 61-74.

COMMISSION OF ALEXANDER SPOTSWOOD. This commission as colonel of the 2d Virginia Regiment is typical of Continental Army commissions used throughout the war. An officer was required to carry his commission at all times. The commission was a printed form showing the person's rank, unit, and date of rank. It was signed by the president of the Continental Congress and certified by the Congress secretary.

During succeeding months the delegates resolved most of the other questions relating to appointment of officers and seniority. Congress strengthened its authority by ruling that officers elected on the same day took seniority according to the order in which their names appeared in the minutes of Congress. Promotions made to fill a vacancy were considered effective on the date that the vacancy occurred. Congress also steadfastly maintained a right to promote officers without regard for seniority in cases of exceptional merit. Delegates from the middle and southern colonies were aware that strict adherence to seniority would allow New England to dominate Army leadership.20

Congress appointed the field officers that the New Jersey Provincial Congress had recommended. Lord Stirling of the 1st New Jersey Regiment and William Maxwell of the 2d were veterans of the French and Indian War, militia colonels, and important politicians. The Provincial Congress raised sixteen companies by apportioning them among the counties according to their respective militia strength. The composition of regiments reflected the territorial subdivisions of the colony. East Jersey, the north

20. JCC 4:29, 342: 6:864; Burnett, Letters, 2:14.

eastern portion, filled the 1st, while West Jersey, the southwestern area, furnished the 2d.21

New Jersey delegate William Livingston secured authorization for a third regiment when Congress ordered the Id to Canada. Its commander, Elias Dayton, had the same military and political credentials as the two other colonels. This regiment was raised on a colony-wide basis during the early spring of 1776. The provincial Congress disbanded its minutemen at the same time. It also created two companies of artillery. These companies, one for East Jersey and one for West Jersey, were regular state troops designed to support the militia. On 1 March 1776 Congress rejected New Jersey's effort to have them adopted as Continentals and its offer to raise two more regiments.22

On 7 March 1776 Lt. Col. William Winds replaced Lord Stirling as commander of the 1st New Jersey Regiment. Matthias Ogden, who had gone to Boston as a volunteer, became the new lieutenant colonel. The 1st and 3d went to New York, although two companies of the latter were briefly diverted to protect Cape May. Washington later sent the 1st to join the Id in Canada and the 3d to serve in the Mohawk Valley.23

Pennsylvania, like New Jersey, was relatively untouched by operations in 1775. Because it lacked a compulsory militia, the Quaker-dominated colony relied on volunteers, known as associators. The Pennsylvania Assembly assumed responsibility for supervising the associators on 30 June 1775. Under the leadership of Benjamin Franklin, the colony's Committee of Safety then began vigorous preparations; by the end of September, it had expended large sums and had drafted rules and regulations for the associators. For the benefit of the large German-speaking minority, the committee printed the regulations in German as well as in English.24

On 12 October 1775 Congress authorized the colony to raise a regiment. The assembly appointed company officers and began recruiting almost immediately, but it did not nominate field officers until November. The companies, recruited across the colony, assembled in the capital on 11 January 1776. At that point the officers objected to the appointment of Col. John Bull as commander and forced his resignation. John DeHaas, veteran of the French and Indian War, replaced Bull. The regiment, with eight companies in conformity with the Continental model, reached Quebec in time to participate in the closing moments of the siege.25

On 9 December 1775 Congress authorized Pennsylvania to raise four more regiments. Congress appointed field officers in early January following the Committee of Safety's recommendations. Companies were raised by counties and grouped into regiments on a geographical basis. Pennsylvania did not call its units regiments but rather designated them as the 1st through 5th Pennsylvania Battalions. Cumberland County's local committee of safety petitioned the Committee of Safety to allow it to

21. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 3:1234-44;

4:164-66, 288, 294-95. American-born William Alexander's claim to the Earldom

of Stirling had been recognized in Scotland but rejected by the British

House of Lords.

22. JCC, 4:47, 123, 181n; Smith, Letters of

Delegates, 3:77, 80, 120-21, 158, 219, 306, 311, 318-19; Force, American

Archives, 4th ser., 4:664, 1391, 1580-1624.

23. Stirling to Samuel Tucker, 3 Mar 76, and Tucker to

Stirling, 7 Mar 76, Stirling Papers; Stirling to Congress, 5 and 19 Feb

76, RG 360, National Archives; JCC, 4: 188, 204, 291. Fitzpatrick,

Writings, 4:526.

24. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:1771-77;

3:496, 501-11, 870-71; Pennsylvania Archives, 1st ser., 4:639-42;

8th ser., 8:7245-47, 7351-52, 7369-80, 7384.

25. JCC, 3:291, 370; Pennsylvania Archives,

8th ser., 8:7306-8, 7314, 7324-25, 7345, 7356. As in the case of the

first two New Jersey regiments, the initial strength of the Pennsylvania

regiment was slightly increased to conform to the standard organization

adopted for Washington's regiments.

ANTHONY WAYNE (1745-96) raised the 4th Pennsylvania Battalion in 1776 and commanded the Pennsylvania Division as a brigadier general during most of the war. In 1792 he replaced Arthur St. Clair as the senior officer of the United States Army and led the Army to victory in the battle of Fallen Timbers three years later. His nickname, "Mad Anthony," did not become popular until after the Revolution. {Portrait attributed to James Sharples, Sr., 1795.)

raise a full regiment, and Congress rewarded this enthusiasm on 4 January 1776 by directing Pennsylvania to raise a sixth regiment there. Congress appointed officers for it according to the county's wishes. One company of every regiment except the 1st Pennsylvania Battalion was armed with rifles, although Congress attached Capt. John Nelson's independent rifle company to the 1st for most of 1776. Congress had accepted that company, organized by the Berks County committee of safety, on 30 January.26

Pennsylvania hoped to retain a voice in the use of its regiments through having them serve as a unified brigade.27 Such a course would also allow it time to train the junior officers, who were considered "pretty generally men of some Education, capable of becoming good officers, [and] willing to do their duty."28 The Canadian crisis, however, prevented any such systematic deployment. Congress quickly ordered north the 1st, 2d, and 4th (under Benjamin Franklin's protege Anthony Wayne). A shortage of arms delayed the movement of the other regiments and led Congress to toy with the idea of arming Robert Magaw's 5th with pikes instead of muskets. The 6th later reached Canada, but the 3d and 5th went only as far as New York City.29

During the summer of 1776 Congress authorized Pennsylvania to raise two more regiments for special missions. In the first instance Congress became concerned with preserving the neutrality of Indians on the frontier. On 11 July it ordered General Schuyler to raise a regiment to garrison several key points in New York and Pennsylvania. Seven of the companies were raised in Westmoreland County and the eighth in adja-

26. Pennsylvania Archives, 1st ser., 4:693-94,

711; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:501, 507-11; Smith, Letters

of Delegates, 3:27-28, 31, 60, 80, 123-26, 167; JCC, 3:29, 101-2,

207, 418; 4:23-24, 29-31, 47-48. The 5th Pennsylvania Regiment absorbed

Nelson's company in 1777.

27. William Thompson to unknown, 25 Jan 76, Pennsylvania

Magazine of History and Biography 35 (1911): 304-6.

28. Lee, Papers, 1 :303-8.

29. JCC, 4:163, 204, 215; 5:431; Force, American

Archives, 4th ser., 5:435-36; 6:664; Smith, Letters of Delegates,

3:376, 420.

WILLIAM SMALLWOOD (1732-92) became the first commander of the 1st Maryland Regiment after leading his colony's opposition to British policies. He rose to the rank of major general and became governor of Maryland after the Revolution. (Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1782.)

cent Bedford County. Westmoreland County had already organized an independent company of 100 men under Capt. Van Swearingen to protect its frontier. On 16 June the Pennsylvania Assembly had accepted this company as a state unit and had stationed it at Kittaning. Swearingen's company became part of the new regiment. Aneas Mackay, a former British officer living in Westmoreland County, was appointed colonel on 20 July, but a food shortage prevented concentration of the regiment until mid-December.30

Mackay's regiment was not responsible for defense of the colony's northern border (Northumberland and Northampton Counties), and Congress authorized a second regiment to secure that region on 23 August. Commanded by Lt. Col. William Cook, it contained only six companies, and it did not complete organization in time to participate in the operations of 1776. By having Cook's unit cooperate with two separate companies from the Wyoming Valley, Congress intended in effect to provide a full regiment to defend the frontier. The valley was claimed by both Pennsylvania and Connecticut, but the latter colony exercised effective control and organized the companies under Capts. Robert Durkee and Samuel Ransom.31

Delaware responded promptly when Congress assigned it a single Continental regiment on 9 December 1775. It appointed company officers on 13 January, and six days later Congress approved the field officers. The regiment assembled at Dover in March and began training under the tutelage of Thomas Holland, the adjutant, who was a former British captain. Several companies skirmished with British landing

30. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1284;

5th ser., 2:7-9; Pennsylvania Archives, 1st ser., 5:92-93. 135;

8th ser., 8:7535-36; JCC, 5:542, 562, 596, 759-60.

31. JCC, 5:699, 701; 6:1024; Pennsylvania Archives,

1st ser., 5:84-85; Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 2:16,

28, 35, 60; Charles 3. Hoadley et al., eds., The Public Records of the

State of Connecticut, 11 vols. (Hartford: various publishers, 1894-1967),

1:7. The Wyoming Valley is now part of Pennsylvania.

parties from the frigate Roebuck, but most of the regiment lacked weapons until July. It obtained muskets in Philadelphia, and in August the regiment set out to join the Main Army at New York City.32

Maryland was not in any immediate danger in 1775. On 14 August it merely reorganized the militia and established forty minutemen companies. Lord Dunmore's activity in Chesapeake Bay, however, caused the Maryland Convention to reconsider the colony's defenses. On 1 January 1776 the convention approved the concept of raising regular troops. Two weeks later it disbanded the minutemen and replaced them with a force of state troops. (See Table 3.) Maryland formed one regiment of nine companies from the northern and western parts of the colony and organized it along lines similar to those of the Continental Army except for the addition of a second major and a light infantry company. The light company, armed with rifles, had a third lieutenant instead of an ensign. It had 64 privates, 4 more than the line companies. The total number of privates in the regiment was the same as in a regiment with eight 68-man companies. The convention also formed 7 separate companies of infantry with 92 privates each, plus 2 artillery companies with the same organization to defend Annapolis and Baltimore.33

The regiment's officers came from the colony's political leadership. Col. William Smallwood, Lt. Col. Francis Ware, and four captains had been members of the Maryland Convention. Both majors had prior service: Thomas Price had commanded one of the Continental rifle companies in 1775, and Mordecai Gist had organized the first Maryland volunteer company in 1774. The regiment and three of the separate infantry companies reached New York on 9 August. The remaining four infantry companies under Thomas Price did not join them until 19 September, after they had been released from coastal defense. When Congress formally assigned Maryland a quota of two Continental regiments on 17 August 1776, the colony simply transferred the regiment and independent infantry companies (equivalent to two regiments) to the Continental establishment without providing a second regimental staff.34

Two other regiments raised during the summer of 1776 drew their manpower primarily from the middle colonies. When the British introduced German auxiliaries, American propagandists condemned them as "Hessian mercenaries," but Congress responded by mobilizing the German-American population. On 25 May Congress authorized the German Battalion. Men of German descent and immigrant Germans were recruited in Maryland and Pennsylvania for three-year terms. Each colony furnished four companies. Congress appointed Maj. Nicholas Hausegger of the 4th Pennsylvania Battalion as colonel; Capt. George Stricker of Smallwood's Maryland light company, as lieutenant colonel; and Ludowick Weltner of Maryland, as major. All three were leaders in the German community. On 17 July Congress authorized a ninth company to be raised in Pennsylvania as a direct result of Washington's recommenda-

32. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 5:745-46,

814-15, 1173; 5th ser., 1:739-41; 2:881-82; JCC. 3:418; 4:68-69,

251; 5:520, 596, 631; Enoch Anderson, Personal Recollections of Captain

Enoch Anderson, ed. Henry Hobart Bellas (Wilmington: Historical Society

of Delaware, 1896), p. 7.

33. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 3:108-12;

4:728-35, 744-53; 5:1528; Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service

of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution. 1775-1783, Archives of Maryland,

vol. 18 (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1900), pp. 4-20.

34. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1474,

1507; 5th ser., 3:87; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:416; 6:72; JCC,

5:665-66.

tion of John David Woelper, a lieutenant in the 3d Pennsylvania Battalion who had served in the French and Indian War.35

Congress authorized another joint unit on 17 June as the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment. Like the 1st Continental Regiment, on which it was modeled, its cadre came from the Continental rifle companies of 1775. Daniel Morgan's Virginia company had been captured at Quebec, but the men of the other Virginia rifle company and of both Maryland companies were at New York and were reenlisted on the same terms as those of the 1st Continental Regiment. Four additional companies were raised in Virginia and three in Maryland, all in the northwestern parts of each colony. Capts. Hugh Stephenson, Moses Rawlings, and Otho Holland Williams became the regimental field officers, retaining their relative seniority. Some of the companies had still not joined the regiment before it was captured at Fort Washington, New York, in November.36

During late 1775 and 1776 Congress thus called on the four middle colonies to raise over 11,000 men for the common military effort. New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware formed ten regiments. Maryland organized the equivalent of two more regiments as state troops, but when Congress asked, it transferred them to the Continental Army. Four other regiments were added during the summer of 1776, two through joint recruiting efforts. Like the first units of other colonies, these regiments attracted men of talent, influence, and experience as officers. Except for Maryland, which behaved more like Virginia than like the other middle colonies, each concentrated on improving its militia and turned to regular troops only at the request of Congress. That fact eliminated most of the variation in organization that had been a problem in the north in 1775 and that was still complicating the southern military effort. As soon as the issue of authority in appointing field officers was resolved, the middle colonies' regiments blended smoothly into the Army. Seven went north, and the equivalent of six others joined Washington's Main Army at New York City.

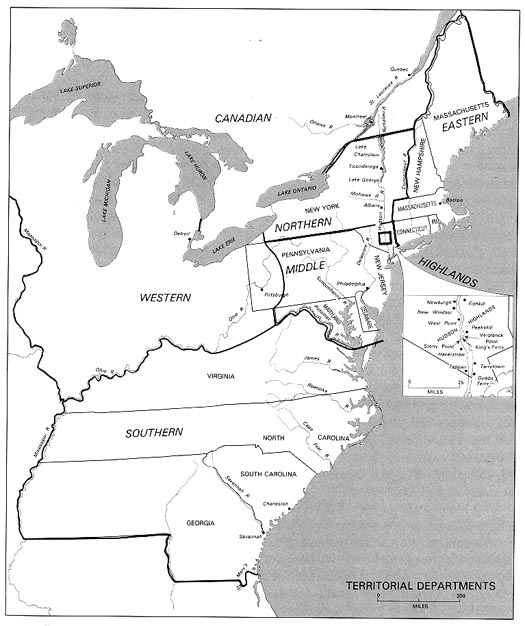

The addition of Continental regiments from the southern and middle colonies raised a new issue of command. Congress reacted by extending the territorial concept that it had implemented with the New York and Canadian Departments. On 13 February it appointed a committee "to consider into what departments the middle and southern colonies ought to be formed, in order that the military operations. . . may be carried on in a regular and systematic manner."37 Following the committee's recommendations, Congress created two new territorial departments on 27 February 1776. Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia became the Southern Department. New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland joined New York as Schuyler's Middle Department. Three days later Congress placed Charles Lee in command of the former and elected six new brigadier generals as subordinate commanders for the new departments. John Armstrong of Pennsylvania, Andrew Lewis of Virginia, and North

35. JCC, 4:392; 5:487-88, 526, 571, 590, 825-26;

Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1508; 5th ser., 1:124, 186-87,

1289, 1293, 1334-36.

36. Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 1:31-32,

183, 251, 1335-37, 1343; JCC, 5:452, 486, 529, 540, 740-46; Fitzpatrick,

Writings, 5:202, 216; 6:128; Burnett, Letters of Congress, 1:518.

37. JCC, 4:132-33.

Carolina's James Moore and Robert Howe went to the Southern Department, while William Thompson of Pennsylvania and Lord Stirling of New Jersey became Schuyler's subordinates.38

Washington remained as Commander in Chief and held command in the "Military District" of New England. Congress intended each of the four territorial departments (Southern, Middle, Northern, and Canadian) to have a major general and two

38. Ibid., 174, 181, 187, 236, 241, 243, 331-32, 364-65; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:252, 270-71, 275-76, 288-89,310-11, 315-19,346-47, 459, 606-7.

brigadier generals. Lee received two additional brigadier generals because his department included such a large area and because Congress believed that it was in immediate danger. Events, however, would doom this symmetry. More immediately, there was a series of transfers and resignations. One of the resulting new appointments was the election of Frederick de Woedtke, on 16 March, as a brigadier general for the Canadian Department. He was the first foreign volunteer elevated to the rank of general, largely on the basis of his claim that he had served as a Prussian general.39

Washington's Main Army retained its organization of three divisions and six brigades in January 1776. The average size of a brigade remained the same, although each now contained only four or five of the larger 1776 regiments. By early March, Henry Knox had accumulated enough heavy artillery to allow Washington to occupy dominant positions on Dorchester Heights, forcing the British to evacuate Boston. Washington correctly guessed that General Howe intended to attack New York and began sending units to that city on 14 March. The regiments went overland to Norwich, Connecticut, where they embarked and sailed the rest of the way along Long Island Sound. He opened his new headquarters at New York on 14 April, and the last of his units arrived three days later.

The shift of the Main Army to New York brought Washington into the area of Schuyler's Middle Department. In the subsequent adjustment of responsibilities, Washington assumed control of the Middle Department and Schuyler reverted to a more limited command over a reorganized Northern Department. The change allowed the latter to concentrate on furnishing logistical support to the Canadian Department which remained as a separate command. New England reverted to the status of a territorial department (the Eastern Department) under Maj. Gen. Artemas Ward. He had wanted to resign, but Congress persuaded Ward to remain at Boston until a suitable replacement could be spared. His forces included an artillery company and five Continental regiments from Massachusetts that Washington had left behind. The 8th, 16th, 18th, and 27th Continental Regiments protected Boston. The 14th occupied the naval base at Marblehead.40

The Main Army in New York now gained some of the new regiments from the middle colonies to compensate for the five left in Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter Washington had to transfer the equivalent of two brigades to the north. In April he regrouped his regiments under the one major general and four brigadier generals he had available for command assignments. Each of the four resulting brigades contained four or five regiments and defended a specific area or terrain feature; the artillery remained outside the brigade formations, although Washington placed the riflemen in the brigades manning the most advanced positions.41 These units formed the nucleus of the Continental forces that would defend New York in August against the onslaught of Howe.

Meanwhile, state units were taking shape in New England to take over the burden of local defense. Washington's policy, established in 1775 and maintained throughout

39. JCC, 4:47, 186, 209-20; Smith, Letters of

Delegates, 3:315-17, 336-37, 342-43, 350-51, 384-85, 387, 406, 440,

633-35; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 4:221-23, 374, 381-82.

40. Ward to Congress, 22 Mar 76, RG 360, National Archives;

JCC, 4:300; 5:694; 6:931; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 4:467-70;

5:1-4; Burnett, Letters, 1:450-52, 505-6; C. Harvey Gardiner, ed.,

A Study in Dissent: The Warren-Gerry Correspondence, 1776-1792 (Carbondale:

Southern Illinois University Press, 1968), pp. 16-19; Samuel Adams, The

Writings of Samuel Adams, ed. Henry Alonzo Cushing, 4 vols. (New York:

G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1907), 3:290-91.

41. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 4:512-13, 535-36; 5:36-37.

the war, left local defense to "the Militia, or other Internal Strength [state troops] of each province."42 The New England governments initially filled their particular military needs by raising short-term independent companies to protect key harbors. On 31 October 1775 Rhode Island took a different course and began raising a 500-man regiment of state troops under Col. William Richmond. On duty since 22 December, Richmond's regiment was expanded in January to 763 men in 12 companies, while Henry Babcock raised a second regiment of the same size. (See Chart 6.) The resulting brigade freed Ward's continentals from a large part of their defensive responsibilities.43

When the New England delegates became quite concerned with the adequacy of the Continental forces under Ward, they produced a study in May 1776 which recommended a New England garrison of 6,000 men. Congress responded first by ordering Ward's five regiments to recruit to full strength. On 11 May it also retroactively accepted the two Rhode Island regiments, which remained in their home state until September, and on 14 May it authorized the other three New England colonies to raise new Continental regiments: two in Massachusetts and one each in Connecticut and New Hampshire.44 New Hampshire's regiment was intended as a garrison for Portsmouth, but chaos resulted from an attempt to use state troops as a cadre, and Col. Nicholas Long made no recruiting progress until August. In Connecticut Andrew Ward recruited his regiment with more success in the Hartford area and in the northeastern part of the state, but on 1 August Washington ordered it to New York. Connecticut also raised two regiments of state troops under Benjamin Hinman and David Waterbury, former Continental colonels, to take over the burden of local defense. Massachusetts did not raise its regiments but placed three existing regiments of state troops under Ward's control with the provision that they could not be sent out of the state. The net result, in terms of the Continental establishment, was an addition of 4 regiments: 2 from Rhode Island, 1 from New Hampshire, and 1 from Connecticut. On the other hand, the Connecticut and Massachusetts state troops released the department's regular regiments for duty elsewhere.45

When Congress completed action on New England, it turned its attention back to New York. British forces had massed in positions from which they could attack New York City by sea and Ticonderoga by land from Canada. Eventually three of the newly raised Continental regiments in New England and all five of the original regiments were transferred to either the Main Army at New York City or to Ticonderoga. Late in May Washington and Congress concluded that a 2 to 1 numerical superiority was needed to successfully defend both locations. On the supposition that the British would employ 10,000 men against Ticonderoga and 12,500 against New York City, Congress decided that the Northern Department should have 20,000 men and Washington's Main Army 25,000. To help achieve these totals, it called on the states for nearly

42. Ibid., 3:379-80. Also see pp. 486-87.

43. R. I. Records, 7:376, 384-86, 403-4,

410, 415, 432-38, 492-93; Rhode Island Historical Society Collections,

6:141-42.

44. JCC, 4:311, 344-47, 355, 357, 360; Samuel

Adams, Writings, 3:288-90; Burnett, Letters of Congress, 2:78-79;

R. 1. Records, 7:537-38, 554, 599-600, 606-9; Rhode Island Historical

Society Collections, 6:154-55, 160-63, 170-73. Smith, Letters

of Delegates, 4:3-4, 31-33, 228-29.

45. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 5:1272-74,

1288, 1296-97, 1312; 6:801-2; 5th ser., 1:3, 314, 404-5, 459-60; 2:805-6;

5th ser., 1:28-29, 48-49, 62-68, 991; 2:805-6; Conn. Records, 15:296-305,

416-17, 434, 485-87, 514-16; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:363, 463;

Ward to Congress, 22 Nov 76, RG 360, National Archives.

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE. John Trumbull, a former Continental Army officer and son of Connecticut's wartime governor, completed this masterpiece while studying art in London during the late 1780's or early 1790's. The colors of the 7th Regiment of Foot, captured at St. John's in 1775, hang on the wall in the background.

30,000 militia: 6,000 for Ticonderoga, 13,800 for New York City, and 10,000 more for a flying camp (mobile reserve).46

Congress' decision to turn to the militia rather than attempt to recruit more Continental regiments was based on practical and ideological reasons. Militia could take to the field quicker. Many delegates also believed that America faced a crisis which demanded the full participation of society for the Revolution to succeed. They felt that the militia, rather than the regular army, was the military institution which represented the peopled All of the colonies from Maryland northward responded to this and subsequent calls for militia, although few furnished their full quotas.

Pennsylvania's contribution to the Flying Camp included two special units of state troops. They contained 1,500 men organized as the Pennsylvania State Musketry Battalion and the two-battalion Pennsylvania State Rifle Regiment. (See Table 3.) Pennsylvania had created them in March to replace the departing continentals. The former unit was expected to defend Philadelphia from British regulars; the latter could serve also on the frontier. The Pennsylvania state troops also included an artillery contingent, but rather than going to the Flying Camp, it remained near Philadelphia to guard the Delaware River defenses. The artillery company had been established in

46. JCC, 4:399-401, 410-14; Fitzpatrick, Writings,

5:56-58, 78n, 218-24.

47. Burnett, Letters, 1:492-94; Henderson, Party

Politics, p. 104; White, "Standing Armies," pp. 95-110; Cress, "The

Standing Army, the Militia, and the New Republic," pp. 134-38.

October 1775 under Capt. Thomas Proctor with twenty-five men. By May 1776 it had increased to one hundred men, and the company volunteered as a unit to serve on the Continental Navy's ship Hornet in an engagement that month with the British frigate Roebuck in Delaware Bay. As a result of that action it was expanded to two companies, and in October the state ordered the men reenlisted for the duration of the war.48

The militia reinforcements and the several Continental regiments that moved to New York during the summer increased the size of the Main Army. Although the militia came with their own brigadier generals, there was still a pressing need for senior officers. Congress responded on 9 August when it promoted Heath, Spencer, Sullivan, and Greene to major general and added six brigadier generals. Only Wooster of the original brigadier generals was passed over for promotion when Congress punished him for his quarrelsome conduct in Canada. The new brigadier generals primarily replaced generals killed, promoted, or captured; in almost every case the senior colonel from the same state was promoted. Congress added several more brigadier generals in September. The additional generals enabled Washington to reorganize his brigades in August before the battle opened in New York. Eight brigades of militia and four of continentals formed three "Grand Divisions." Each division was a different size, to fit its defensive mission, but all contained both militia and continentals. This mixture continued throughout the New York campaign as other brigades were added.49

In mid-September the Main Army's fourteen infantry brigades contained 31,000 officers and men.50 Over 7,000 were sick, although most were not sufficiently ill to be hospitalized. Another 3,500 were on detached duties. Fifty-seven percent of the total strength came from 36 regiments of militia and 4 regiments of state troops. The 25 Continental regiments accounted for 674 officers, 103 staff officers, 602 sergeants, 314 drummers and fifers, and 11,590 rank and file. Only slightly more than half of the rank and file were carried as present and fit for duty: 3,153 were sick and 2,356 were "on command." Nearly two-thirds of the total on special duties were continentals rather than militia, a significant indication that they had better training. The regiments were reasonably complete. Half were over three-quarters full, if one includes the sick and detailed personnel. The eight which fell below two-thirds all had special reasons for their status. The 1st Continental Regiment was in the process of reorganizing, and the others had suffered heavy casualties in the battle of Long Island several weeks earlier. These figures indicate that only a fraction of Washington's large army consisted of trained, reliable troops. On the other hand, his regular regiments were reasonably close to their prescribed organization and had the potential for performing well in battle. It is also of some note that although the Main Army still drew the majority of its men from New England, units from as far south as Virginia were present.

The expansion of the Continental Army in 1776 required enlargement of the staff serving the Main Army and the creation of staffs in the territorial departments. Other changes in staff came because individuals were promoted or resigned. Adjutant General Gates and Mustermaster General Stephen Moylan, for example, were promoted

48. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 3:1819-20,

1828; 4:524, 1573-75; 6:961; 5th ser., 1:1317; 2:69, 80, 97; Pennsylvania

Archives, 1st ser., 4:751-52, 780; 5:33; 8th ser., 8:7429-46, 7461-65.

49. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:379-81, 422-23, 501-3;

6:3-4, 207-8; Burnett, Letters, 2:45-57; JCC, 5:597, 641;

6:898.

50. General Return, Main Army, 14 Sep 76, RG 360, National

Archives. This return does not include the Flying camp or various regiments

such as the Delaware Regiment that were not physically with their brigades

on that day. Lesser, Sinews, pp. 32-35, prints another return from

28 September.

GEORGE CLINTON (1739-1812) performed double duty in the Revolution. He was New York's first elected governor as well as a brigadier general in the militia and later in the Continental Army. He played a key role in efforts to defend the Hudson Highlands throughout the war. (Portrait by John Trumbull, 1791.)

during the year. Joseph Reed was persuaded to accept the Adjutant General's office with the rank of colonel; his former law student, Gunning Bedford, succeeded Moylan, moving up from deputy mustermaster general. Their personal relationship ensured that the two administrative departments would work in close cooperation. At the same time, Washington instituted a more comprehensive reporting system that gave him up-to-date information on the state of his army. His British opponents did not enjoy a similar system and consequently were at a disadvantage in planning.51

The other major administrative section of the staff, Washington's personal aides and secretary, also experienced changes. Increases in pay and a congressional decision to give the Commander in Chief's aides the rank of lieutenant colonel (major generals' aides were majors) eased misgivings about career development. When the expanded size of Washington's army greatly increased the workload of his personal staff, Congress added a fourth aide on 24 August. New aides during 1776 were Samuel Blatchley Webb, Richard Cary, and William Grayson. The aides were supplemented by a new special unit formed on 12 March 1776, the Commander in Chief's Guard. Four men from each regiment at Boston were selected for the unit, which was commanded by Capt. Caleb Gibbs (formerly adjutant of the 14th Continental Regiment) and Lt. George Lewis, Washington's nephew. These officers served as supplemental aides, with Gibbs acting as headquarters commandant and running the household. The unit protected Washington's person, the army's cash, and official papers.52

Comparable expansion took place in the areas of logistical and medical support.

51. JCC, 4:177, 187, 236, 311, 315; 5:419, 460;

6:933; 10:124; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1013-14; Fitzpatrick,

Writings, 4:202-7, 223; Greene, Papers, 1:264-65; British

Headquarters Papers, nos. 1894, 2443, 3320 (Charles Jenkinson to Henry

Clinton, 5 Apr and 23 Nov 79 and 5 Feb 81). In 1776 reports required a

ream of paper a month per regiment.

52. JCC, 4:311; 5:418, 613; Fitzpatrick, Writings,

4:287, 369, 381, 387-88; 5:50, 125, 165, 337-38, 481; Carlos E. Godfrey,

Commander-in-Chief's Guard: Revolutionary War (Washington: Stevenson-Smith,

1904), pp. 19, 35-38. In 1776 Washington also had an assistant secretary,

Alexander Contee Harrison, and Congress appointed the French arms exporter

Pierre Penet an honorary aide.

An important innovation occurred on 29 June 1776 when Washington organized a provisional artificer regiment. It was placed under the command of Col. Jonathan Brewer, the barrackmaster, and Deputy Quartermaster General John Parke. The regiment's hired or enlisted craftsmen continued to perform maintenance and construction duties, but they were now assembled into twelve companies for emergency combat duty. Each of the fifty-man companies was given a temporary captain and two lieutenants, mostly former enlisted men or civilians. Seven companies were composed of carpenters, three of smiths, and one of special nautical carpenters. The final company acted as a general maintenance organization. The regiment was dissolved in November.53

Although Congress attempted to provide each territorial department with competent military engineers, men with special skills remained rare. Washington brought only Rufus Putnam and Jeduthan Baldwin with him to New York. Putnam served as the Main Army's chief engineer, with assistants merely detailed from the line regiments. Baldwin went to the Northern Department where he operated at Ticonderoga under similar conditions. Both men were rewarded with the rank of engineer colonel, but the lack of special skill at designing fortifications which came only through formal education created weaknesses in the defenses at New York and Ticonderoga. Energy and resources were wasted on works too extensive to be manned adequately by the available forces.54

As a capstone to the creation of the larger Continental Army, Congress created a special standing committee to oversee the Army's administration and to make recommendations to Congress. On 24 January 1776 Edward Rutledge, echoing Washington's own concerns, suggested that a war office, similar to Britain's, be established. Washington's pressure and the sheer volume of military business led Congress to establish the Board of War and Ordnance on 12 June. Five delegates, assisted by a permanent secretary, Richard Peters, assumed responsibility for compiling a master roster of all Continental Army officers; for monitoring returns of all troops, arms, and equipment; for maintaining correspondence files; and for securing prisoners of war. The title reflected Congress' deliberate decision to reject the British practice of separating the artillery and engineers from the rest of their troops. The office began functioning on 21 June.55 Washington heralded this action as "an Event of great importance [which] will be recorded as such in the Historic Page."56

The original plans worked out by Congress, Washington, and Schuyler in 1775 projected a small Continental Army for 1776. Twenty-six infantry, one rifle, and one artillery regiment were allocated to the Main Army and another nine infantry regiments to the Canada-New York army. Standard tables of organization ensured that the regiments would be uniform. When Great Britain committed major forces to North America and expanded the range of the conflict, however, Congress and the individ-

53. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:197, 270; Force, American

Archives, 5th ser., 1:765-66.

54. JCC, 5:630, 732; Fitzpatrick, Writings,

5:5, 11, 108, 412; Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal, pp. 17-34,

62-63; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:38, 274, 471-72.

55. JCC, 4:85, 215; 5:434, 438; Smith, Letters

of Delegates, 3:148. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:128-29, 200-201.

56. Fitzpatrick, Writings, p. 159.

ual colonies reacted by adding units beyond the number required by the initial, modest plan.

This haphazard growth eventually produced a national military institution in a geographical sense. Congress set up a network of territorial departments and added general officers and staff personnel to provide a coordinated command organization. Although many of the new regiments adopted the standard Continental regimental structure, differences in other units reflected the individual factors which had prompted their creation. Bringing these units into conformity remained a major task if the Army were to become a national institution in every sense.

The units in the north, at Charleston, and at New York City during 1776 came from a wider range of colonies than those that had assembled at Boston and in Canada in 1775. Despite some loss of internal homogeneity, the major field armies in 1776 worked well together. The need to mix militia with the Continental regulars, however, created a new set of problems that became most evident during the defense of New York City against the major British attack that opened in late August.

The American army in Canada was repulsed, but the military situation in the north stabilized after the troops withdrew to Ticonderoga. The forces in the south easily defeated Britain's small efforts to restore royal authority there. Washington's Main Army forced the British out of Boston in March but ran into serious trouble in the defense of New York. General Howe, commanding the largest British army gathered at one place in America during the war, outmaneuvered Washington's mixed force of continentals and militia, first on Long Island and then on Manhattan. The British landing at Kip's Bay on 15 September, which scattered two militia brigades in a humiliating rout, marked the lowest point of this phase of the campaign.

The next day, however, a relatively minor skirmish at Harlem Heights began to restore morale. The aggressiveness of a recently formed provisional unit, Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton's rangers, supported by the rifle companies of the 3d Virginia Regiment and later by other troops, drove off a British force which included the elite 42d Foot (Black Watch). Other skirmishes at Pelham and Mamaroneck contributed to a restoration of confidence, at least in the Continental units. But it was a temporary resurgence, and worse defeats were still to come. To Washington the major lesson of 1776 was simply that militia could not meet British and German regulars on equal terms. Still smarting from the loss of Long Island, he wrote to the President of Congress on 2 September 1776 that

57. Ibid., 6:5.

page updated 4 May 2001