FORT WAINWRIGHT, Alaska -- (October 5, 2012) The land that U.S. Army Garrison Fort Wainwright manages in Alaska has a long history. People have been living here since the end of the glacial period, approximately 13,000 years ago. Over 600 prehistoric archaeology sites are known from their discovery on Army lands between Fairbanks and Delta Junction.

Non-glaciated areas like those in Interior Alaska stretched from the Canadian border to Siberia and provided a corridor for small bands of nomadic people to travel between the continents.

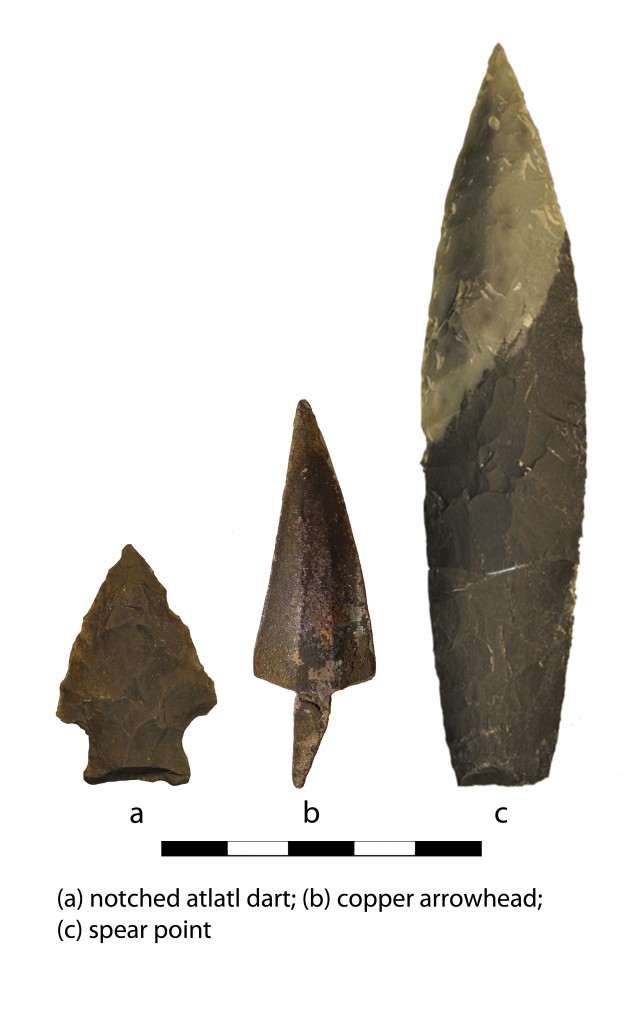

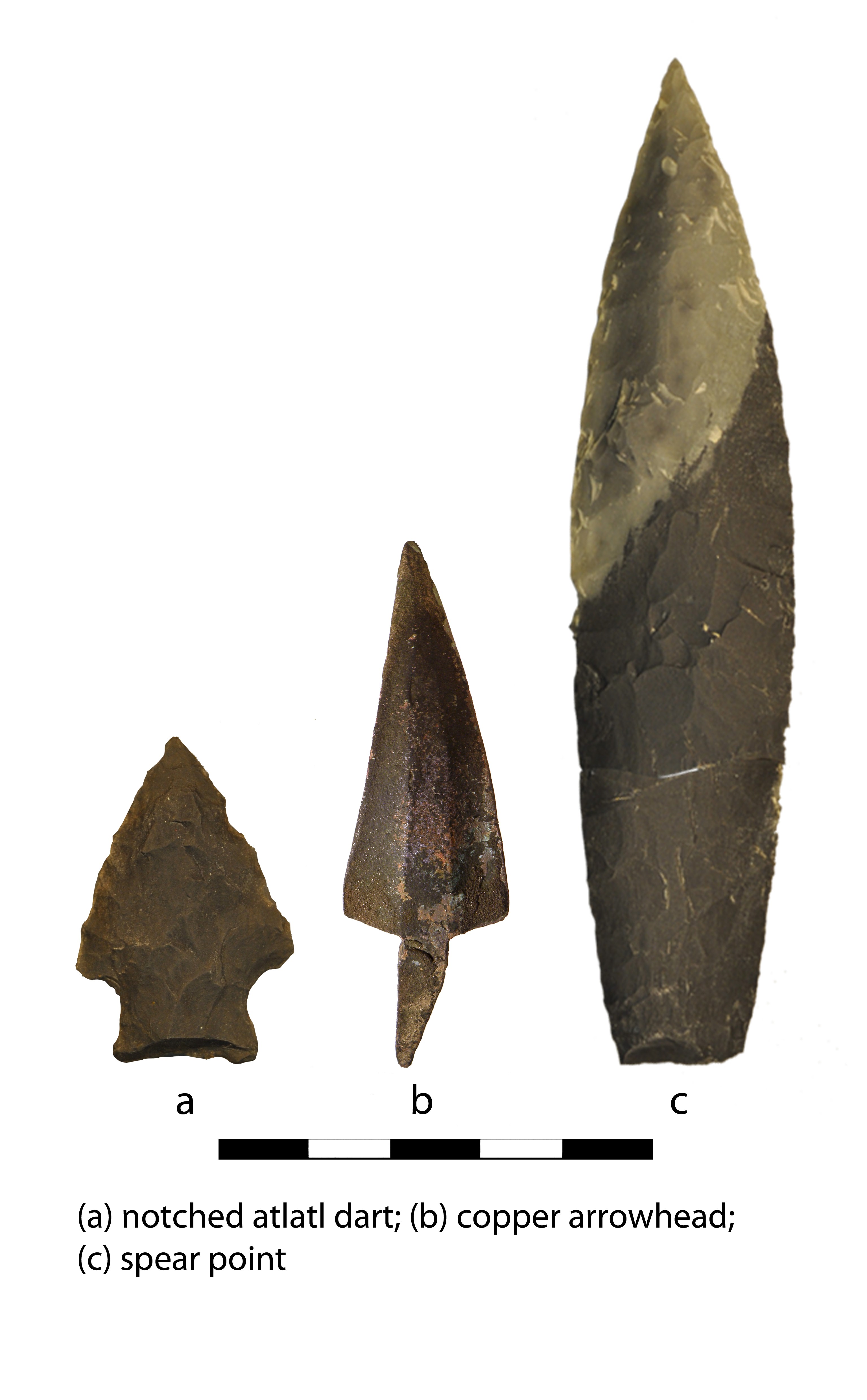

The earliest sites on Army lands are found on ancient dunes and river terraces in the Tanana Flats Training Area. At 12,000 years ago, people hunted large mammals such as bison and mammoths with heavy spear points. Archaeology sites contain remains of meals at hunting camps and debris from creating and sharpening stone tools.

Boreal forest vegetation moved into Interior Alaska by about 8,000 years ago. Sites dating to this time period are found in the Donnelly Training Area (DTA) near Delta Junction. Prehistoric hunters used throwing spears, known as atlatls (pronounced at-lat-tils) tipped with notched-stone darts to kill their prey.

At the Banjo Lake site in the DTA, charcoal from ancient campfires was radiocarbon-dated to find out when people were living at the site. Radiocarbon dating measures the ratio of carbon molecules in a sample and can estimate within several decades when wood or bone was burned in a fire. Using this method, the Banjo Lake site was found to be 6,500 years old.

The campers at this site prepared game, cooked meals, and repaired and replaced their stone tools. To make tools, they found chunks of chert in river gravels, located nice pieces of local basalt and rhyolite and traded or travelled far distances for highly coveted stone such as a volcanic glass known to geologists as obsidian.

A scientific technique called x-ray florescence analysis can be used to detect the chemistry of individual rocks, and each lava flow that produced obsidian has its own chemical signature. This allows archaeologists to trace obsidian back to the area from which it originated.

Obsidian artifacts found at the Banjo Lake site at DTA were made from cobbles that travelled with prehistoric hunters nearly 300 miles southeast from the Batza Tena volcano and 175 miles northwest from Wrangell Mountain.

Interior Alaska can be traced back almost 2,000 years. Artifacts associated with the ancient Athabascan culture are exceptionally diverse and include bone and antler projectile points, fishhooks, beads, buttons, birch bark trays and bone gaming pieces.

In the Upper Tanana region, copper was available and used in addition to traditional material types to manufacture tools such as knives, projectile points, awls, ornaments and axes. Bow-and-arrow technology likely moved into central Alaska approximately 1,200 years ago. Wood arrow shafts were commonly tipped with bone, antler, stone or copper arrowheads.

A 300-year-old-copper projectile point was found at a late prehistoric site in the DTA. The point was hammered into shape from a natural copper source in the Copper River Valley 150 miles southeast of Fort Wainwright.

When you are out hunting, hiking or training on Fort Wainwright and its training lands, look around and imagine how people might have been walking on the same landforms hundreds or thousands of years before you.

These areas are rich in history, and we should all tread lightly on the landscape to preserve traces of past cultures. If you encounter a stone tool or archaeology site in your travels, please leave artifacts in place.

Valuable information can be lost forever if a site is disturbed, even if only a single artifact is moved. You can contribute to the growing database of archaeological knowledge if you can mark the point on your map or take a location with your GPS and call the Directorate of Public Works, Environmental Division Cultural Resource manager at (907) 361-3002.

Social Sharing