The words "Back to School" mean "continued education" in many cultures. But not everyone returns to school the same way. For some "back to school" means a trip to the local electronic equipment store for upgrades and gadgets, the school supply store to ensure they have the required traditional accessories, and new uniform or clothes.

For students at Makongo, JiteGemee and Air Wing High Schools in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Africa, school supplies are a note pad and a pen and pencil. Uniforms are simple and sometimes hand-me-downs, and as for electronic equipment and gadgets--there aren't any.

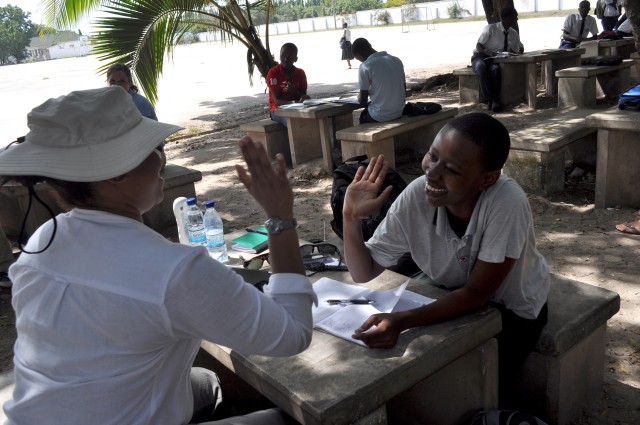

But what they did have this year were Cadets from ROTCs Cultural Understanding Language and Proficiency program to aid and enhance their English education--native English speakers to teach conversational English.

The CULP program allows Cadets to travel to foreign countries on humanitarian, English teaching or military-to-military missions. In this way the Cadets can learn that theirs is not the only culture in the world, and so they can better understand different value systems, social norms and the different ways other people do things.

But if you ask the students and staff, the education the Cadets were getting in cultural differences was a good trade off for the education the Tanzanians were getting from them.

Celestine Mwangasi is the head master at Makongo High School in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He said that his staff was excited having the Cadets on campus to teach because they, "have a new approach to teaching, new methodology and new information from outside of Tanzania."

But he added that there was something more to be learned, from both sides.

"This program has added something between Tanzania and the U.S. We learn about the U.S. through Cadets," he explained. "And I believe Cadets learn too because I think they see, and not hear a rumor. (Now) our brothers and sisters can know each other and learn from each other."

The Cadets' new-found teaching abilities did not go without their own "back-to-school" lessons from Dr. Thomas Smith, the director of instruction for the mission.

Smith, who is contracted through North Georgia College and University, is a professor in English, writing and research, and teaches high school civics, government, geography and history.

He was not only responsible for teaching English and giving instruction on how to teach but he supervised the Cadets and was responsible for the academic credits the Cadets received teaching English, via North Georgia College and University. He graded the research paper, journals, textbook evaluations, and overall performance of each Cadet.

"I love working with teenagers, guiding them and sharing experiences so they can better understand and be successful," he explained. "I taught English (in) many countries in the world as second language and realized the importance of teaching for business and world communication, and the value of how it builds relationships. It serves as that common bond that ties people together."

The result of Smith's work with the Cadets was a new-found understanding of how to teach their native language to people who don't speak it.

Cadet Robert Wolpert, who attends Bowling Green State University, said Smith's lessons involved how to go through objectives of what you are going to teach and then you teach it without talking too much.

"(We learned to) teach (students) the vocabulary and then use a marker sentence," he explained."They know vocabulary from repetition, (but marker sentences teach) what a word really is and how to use it. So if I point to the word 'dog' they know what it is, not just to know the word 'dog.'"

"You want to make the classroom a fun environment. What doctor Smith taught us was helpful and the tips were useful."

Charles Msumule, who is the education coordinator at Makongo High School, said he also learned from the Cadets, though not through classroom instruction.

"CULP is important because it has brought understanding to me about America, its culture, and its people more (closely) than ever before," Msumule explained. "Because I used to hear and used to see things but now I can ask them many questions and meet Americans, and ask them about their systems and ask about how we can do (similar things)."

He added that the mission the Cadets were on--to teach English--is important for Tanzanians because it is a second language in Tanzania, tourism is a big industry for employment, and because of the education stratification.

"English connects us worldwide. It is important because it is easy to communicate anyplace you go because everyone knows some English," he noted. "Also, our school system in Tanzania uses English as a median of instruction for all areas, except one. So for them, English is the key toward the learning process."

The Cadets were divided into three groups to cover the three schools at which they were teaching. There are no computers in the classrooms, and in fact the only reason Makongo has a computer lab--with 14 computers for the entire school, is because of a generous donation.

At these schools the buildings were made of cinder block construction, tin roofs, open windows with two-inch square wire panels covering them, doors that stood open and faced a center assembly courtyard, and only a few had working ceiling fans. Makes-shift black boards adorned the front and sometimes back of the classrooms, there was a light coat of paint on the wall, and old metal framed, wood top desks crowded the center of each room.

Cadet Ashley Janovick, who attends Vitereo University, said that teaching the students wasn't as simple as it might seem because, while they have a good grasp of vocabulary, they don't speak it enough to know how to use it. And conversational English is different than learning vocabulary.

She added that there was a valuable reason for the students to learn English, besides it being a language class. It would help them get jobs.

"The upper grades are all conducted in English, and English is the second language here," she explained. "Also, this area is supported by tourism and the students must understand and communicate well in English so they can get jobs when they graduate."

Janovick said that the lack of technology was obvious, but thanks to a handheld device her group brought alone, they were able to overcome some language barriers.

"The students don't have laptops and while the school has a computer lab there aren't enough computers for the class to all use them," Janovick said. "We had a (tablet device) that we could pull up pictures of things to show the students. So when we would try to teach them how to, for example, order a meal in a restaurant, we would make the menu out on the chalk board and then show them pictures of anything they couldn't relate to."

This experience was more than just about Cadets teaching English--it was about Cadets learning that although cultures may be different, people are all essentially the same.

"Coming here as an American you see that you aren't anything special or superior," explained Wolpert. "And this has taught me in the future to learn the culture and make some friends before I get down to business. I saw that when you interact with everyone, you learn to respect the culture and if they want to talk for an hour before you get down to business, then that is what you do."

"(Different cultures) have different incentives for doing things, and the institutions that govern their lives are completely different than the ones we have in America," noted Cadet Christian Elliott, from George Washington University. "And yet we have these fundamental similarities that make it easy for us to connect and share and trade experiences. We learn the same way, we teach the same way, and there is that common human portal where we can exchange ideas and cultures despite how different we are.

"If you can understand those commonalities and similarities between people it goes a long way toward working with others and building a team."

Social Sharing