REDSTONE ARSENAL, Ala. (Feb. 15, 2012) -- Marine Reserve Col. Matthew Bogdanos is very much like a tour guide, taking his audiences on a journey deep into ancient history.

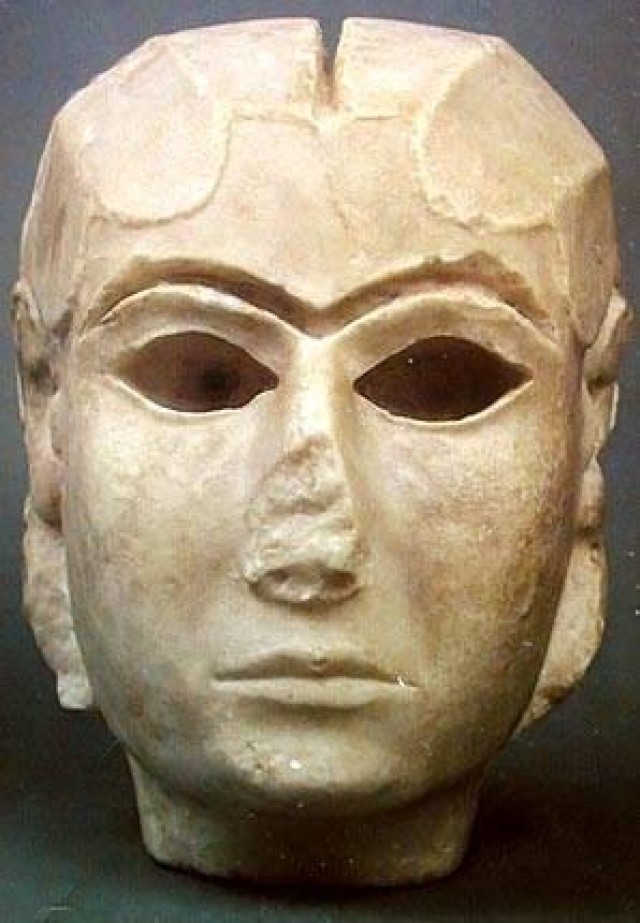

He sprinkles his comments with quotes from Socrates, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Shakespeare's Hamlet, and shows images of such artifacts as the Sacred Vase of Warka, the Golden Bull's Head, the Bassetki Statue, the Fabled Treasures of Nimrud and the Mask of Warka, the first human face ever carved in stone.

But Bogdanos' story is not so much about ageless artifacts as it is a tale of the journey taken to restore the symbols of ancient history missing from the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. His presentation kicked off the Huntsville Museum of Art's new lecture series titled "Voices of Our Times" on Thursday.

"This is a journey of passion, courage and trust. It is as crucially important as our shared cultural heritage," Bogdanos said.

"These are my memories and my impressions of the warm Afghan people and the integrity of the Iraq people. It is about the importance of history and about the living, breathing testaments of our shared cultural heritage."

Bogdanos' experiences as a Marine colonel on a quest to find and restore the museum's artifacts are retold in his bestselling book "Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine's Passion to Recover the Worlds' Greatest Stolen Treasures." Proceeds of the book, now in its fourth printing, are donated to the Iraq National Museum.

In his comments, Bogdanos took his audience back in time to Baghdad 2003 "when combat reigned throughout the city. The regime had left. There was lawlessness and looting everywhere. There was total abject violence. Every building of the regime was destroyed, including the Iraq National Museum that had a collection of over 5,000 separate priceless relics of our shared cultural past and over 170,000 ancient artifacts from the very cradle of civilization."

The museum had been closed to the Iraq people for 24 years. When the regime fled, those relics and artifacts were stolen within 24 hours, and the 120 administrative offices of the massive museum were destroyed. Soon after, Bogdanos led a special team of investigators that eventually recovered more than 6,000 of Iraq's treasures from eight different countries.

But Bogdanos' story starts long before his five-year treasure hunting expedition. He told his audience how at age 19 he joined the Marine Corps and served from 1980-88, when he joined the Marine Reserves and pursued a high profile career as a tough New York City district attorney, and also continued his interests as a middleweight boxer and classics scholar. As a Marine reservist, he led a counter-narcotics operation on the Mexican border and served in Desert Storm, South Korea, Lithuania, Guyana, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kosovo.

Bogdanos lost good friends and his New York City apartment in the World Trade Center attacks of 9/11. He returned to active duty, joining a counter-terrorism task force in Afghanistan, where he received a Bronze Star for actions against al-Qaeda.

"We were a U.S. government experiment of a single team with representatives from each of the different categories in government responsible for counter-terrorism, including the FBI, the CIA, U.S. Customs Office and the four branches of the military. The team joined together each agency's unique statutory authority and skill sets."

In Afghanistan, the Special Forces Counter-Terrorism Team lived with the people, wearing civilian clothes to fit in, becoming part of society, gaining trust and eventually succeeding in their mission against al-Qaeda. The experience also taught Bogdanos about the Afghan people.

"Islam is a religion based on duty, faith and obedience that has been turned into something else by the Taliban," Bogdanos said. "The abuses against women in Afghanistan are true, but they pale against the abuses made against children."

The team returned to the U.S. in April 2002. Bogdanos was promoted to colonel and put in charge of the team as it took on its next mission in Iraq.

"We were tracking down evidence of terrorist activity and terrorist financing," he said. "Saddam Hussein, like most dictators, was ruthless in the requirement of record keeping."

Going through some of the 67 presidential palaces in the country, the team uncovered filing cabinets filled with $100 bills and gold bars. And along the way, they learned about an art raid through a reporter with the British Broadcasting Corp.

"I volunteered a portion of my team for antiquities investigation," Bogdanos said. "I told the general of the U.S. Central Command that we could fix this in three to five days. It took a little over five years."

The museum, consisting of 11 buildings on 12 acres in downtown Baghdad, turned out to be a fortified military position with rocket propelled grenades found throughout the museum grounds. While the administrative offices had been ransacked and destroyed, the museum's 28 galleries looked untouched, except for the empty display cases. Further deep inside the museum, 30 non-descript storage lockers were emptied of their treasures.

"Those cases were emptied long before the war," he said, adding the only possible explanation was that the thefts of many artifacts were the result of inside jobs by professionals.

The team set up an amnesty program that allowed the Iraqi people to return anything they took from the museum, no questions asked. The team again became part of society, "learning the rhythm of the neighborhood and building bonds of trust."

During eight months, 2,000 pieces were returned by the Iraqi people. Eventually, over 95 percent of the pieces taken by the people were returned.

The team also conducted raids for the lost treasures. With many antiquities leaving the country in shipments of weapons, the team followed up on all tips and reclaimed such treasures as a 5,000-year-old vase hidden in a car trunk with weapons and the Bassetki Statue found in a cesspool covered in grease.

But the most valued items -- 31 in all -- were taken by professionals. The team was able to recover 16 of those. Many of those pieces followed a trail that often is taken by stolen treasures, going from Baghdad to Damascus to Beirut and to Geneva, where bidding begins and then the treasure travels to places like London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Amman and Dubai before becoming a part of someone's private collection.

"Until every single piece is returned to the Iraqi people, I don't feel this mission is complete," said Bogdanos, who received a National Humanities Medal from President George Bush for his work in recovering more than 6,000 of Iraq's treasures.

But the Marine, who went on to deploy again to Afghanistan, and also to the Horn of Africa and two more tours in Iraq before returning to the Marine Reserves and the New York City district attorney's office in 2010, said the real treasure for the war-torn countries of Afghanistan and Iraq are the voices of their children and the laughter of their people.

Social Sharing