BAGHDAD (Army News Service, Dec. 11, 2007) - On a bright afternoon, Dave Matsuda traveled with a group of U.S Soldiers to tour a food distribution depot in the Ur neighborhood. The Soldiers were worried about how to keep the depot from being infiltrated by Moqtada Al Sadr's Shi'ite militia army, which controls that part of the Iraqi Capital.

The chief of security at the depot, however, assured them the warehouse was safe, because his "organization" protected it from Sadr's influence.

The Soldiers were doubtful the warehouse was safe. The chief's independence seemed inexplicable given what they knew about the area - it was a puzzling anomaly in a sea of data pointing in the other direction. Professor Matsuda, though, believed he could put the pieces of the puzzle together.

He began asking the chief questions about his family, his extended family, his tribe, and the tribe's affiliations with other tribes. Later, he was able to chart the relationships on a diagram to show how the chief's tribal hierarchy operated, giving the Soldiers a rare glimpse into the complicated inner workings of Iraqi society.

It was a valuable insight drawn not from standard military intelligence gathering techniques, but from the science of anthropology.

"A military person would say 'Let's look at this in political or military terms,'" Prof. Matsuda said, "but an anthropologist says, 'Let's look at the tribal relationships underneath everything."

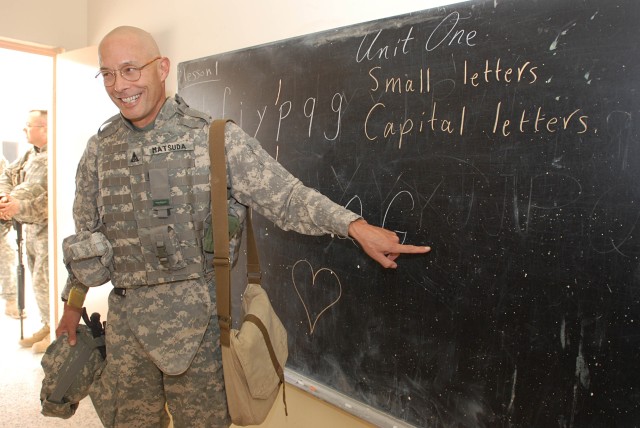

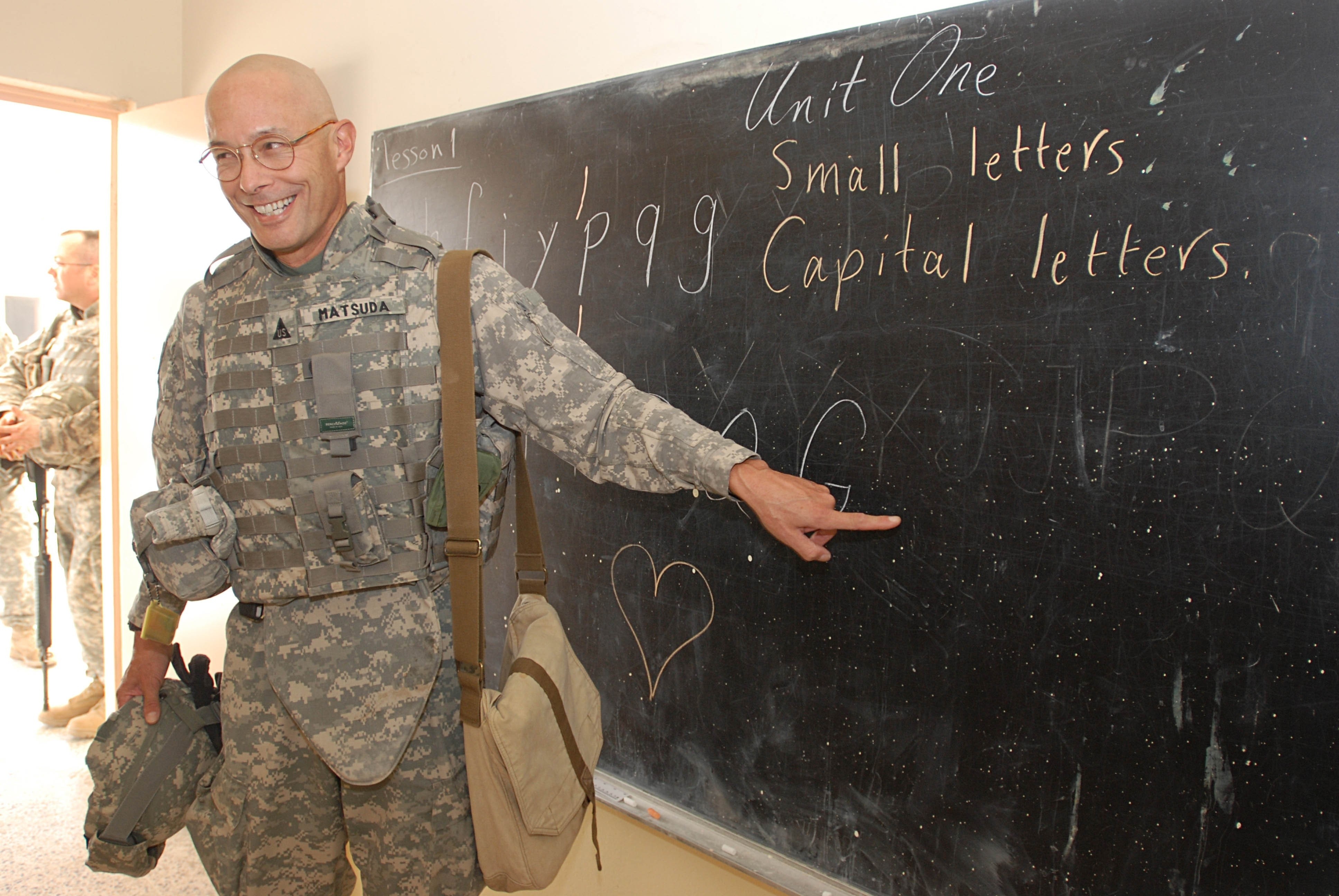

There's a reason Prof. Matsuda knows what an anthropologist would look for: he is one. Back home, Prof. Matsuda teaches at California State University, East Bay. He holds a double doctorate in anthropology and developmental psychology. Tall, soft-spoken, and bespectacled, he fits the image of the bookish professor perfectly. But these days, Prof. Matsuda has traded in his professor's tweeds for combat boots and a bullet-proof vest. In September, he brought his expertise to Iraq as part of a small group of cultural experts called the Human Terrain Team, which is attached to the 82nd Airborne Division's 2nd Brigade Combat Team operating in Northeast Baghdad and Sadr City.

The HTT's mission is to diagram Iraq's cultural landscape - its "human terrain" - in the same way intelligence analysts map out Iraq's cities, roads, and rivers. It's a function that has become increasingly important as the U.S. military has turned its focus to counterinsurgency operations, in which cultural understanding is the key and knowing the human terrain is absolutely essential, said the team's leader, Lt. Col. Edward Villacres.

<b>The Team</b>

The 2nd BCT's Human Terrain Team uses history and social science to provide cultural awareness that supports the brigade's operations, Lt. Col. Villacres pointed out.

HTT consists of the team chief, an area specialist, a social scientist, and a research manager. Prof. Matsuda, the social scientist, is a civilian, while the other members are active-duty Army with specialized knowledge. All team members have specialized knowledge specific to their HTT jobs.

"We've got people who know the culture in and out," said 1st Lt. Sami Tioni, the team's research manager and a native Arabic speaker.

To accomplish its mission, the team draws on two pools of knowledge: information that has already been collected and information the team members collect themselves. They then analyze the information and present their conclusions and advice to the brigade commander.

"It gives him an additional level of insight as he prepares to make decisions," Lt. Col. Villacres said.

Officials with the 2nd BCT said they appreciate the contributions the HTT has made to the brigade's operations so far.

"They add a critical dimension to the fight, one that has been missing up to now" said Lt. Col. David Oclander, the 2nd BCT's executive officer.

Outside the military, however, the teams have sparked some controversy. Much of the opposition has come from people in the academic world, who, according to Prof. Matsuda, fear the army will misuse the knowledge offered by social scientists.

"Some are saying anthropology can't be part of the Army without being corrupted," he said.

Prof. Matsuda said some of the concerns are valid, and some are motivated by knee-jerk anti-militarism. Regardless, he said, the stakes are too high in Iraq right now to sit on the sidelines.

<b>Knowing the Script</b>

Even though Operation Iraqi Freedom is in its fifth year, Lt. Col. Villacres said many in the U.S. military still fail to appreciate the differences between Arab and Western culture.

"Arab society doesn't have any of the common foundations we have," he said.

As a result, it can be difficult for Iraqis and U.S. Soldiers to find common ground, despite good intentions on both sides. Prof. Matsuda gave as an example an instance where U.S. Soldiers thought they had settled a dispute with people in a village by making a condolence payment. But when the Soldiers returned a few days after making the payment, they were attacked. The Soldiers thought they had been betrayed, but in the villagers' eyes, the agreement had never been valid because the traditional reconciliation ritual hadn't been conducted, Prof. Matsuda explained.

Anthropologists believe all societies operate according to a certain "script," Prof. Matsuda said. Iraqis have one script, Americans have another. The HTT's mission is to provide an interpretation of the Iraqi cultural script that will help Soldiers make the right decisions.

The team has carried out that task in ways both small and large. One small way they affected operations came when the brigade was about to put out a wanted poster featuring an image of the scales of justice. Prof. Matsuda pointed out the idea behind the scales of justice was a Greek-derived, Western concept that meant nothing to Iraqis. Instead he proposed changing the poster to show two open hands - an image drawn from ideas in the Quran - in order to make it more resonant with Iraqis.

"We try to find the assumptions and motivations behind what people do," the professor said.

<b>Why it Matters</b>

First Lt. Tioni said the value of insights the HTT offers shouldn't be underestimated.

"We fight an enemy who is very fluid, and the only way we're going to defeat them is by knowing the culture," he said.

The team's work isn't simply an academic exercise, team members said. First Lt. Tioni said he is convinced greater cultural awareness will help protect Soldiers out on the streets and knowing how to interact with the population is what's going to save lives.

In justifying his work in Iraq, Prof. Matsuda returned to the example of the Soldiers who were attacked even after making a condolence payment because they didn't understand the importance of cultural traditions.

"I don't want those guys going into that village thinking they got it all taken care of and they end up getting shot," Prof. Matsuda said. "I want everyone to come home."

(Sgt. Mike Pryor serves with 2nd BCT, 82nd Abn. Div. Public Affairs

Social Sharing